Every Friday afternoon, the Ikon Model Management agency in Manhattan holds an open call for aspiring models. The tiny waiting room fills quickly with applicants who sit, legs tapping, on cushioned benches. Lemonade walls and the endless trickling of a waterfall create an atmosphere of false serenity. The receptionist types primly and pretends the applicants aren’t there. Everyone stares suspiciously at one another.

Today, Kimy was lucky enough to get a seat. With her black hair and cowboy boots, she looks like a dark shadow against the sugary sweetness of the décor. She’s six foot three and thin. Spidery eyelashes veil her gold-specked green eyes, and what little skin she does reveal — her face and hands — glows warm and brown. People on the street often ask her if she’s a model, which is why she’s decided to try and actually become one — that, and the money is good.

A woman in pearls and kitten heels finally appears. She starts accepting portfolios, but Kimy didn’t bring any photographs — the website states that none are needed to apply at open calls. “Sorry, we need photos,” snips the pearls. Out of luck, Kimy packs up her things and leaves.

Kimy is tired and doesn’t have enough money for a MetroCard. She walked over twenty-five blocks to get here and has no permanent residence. Kimy is also biologically male, which she thinks might be the reason she hasn’t been able to break into the modeling world so far. Being a homeless transgender teen does not make it easy to get any sort of break.

Morning rituals

At a quarter to eight in the morning in west Manhattan, the air by the freeway carries the balminess of early spring and the crisp chill brought by the night. There’s the dull pungency of gasoline fumes and the slapping of tires on asphalt. The traffic thickens as the sun comes up, shining on commuters hurrying to work, the rush of taxicabs, and footsteps.

Sylvia’s Place, a few blocks from the West Side Highway, shares a small space on 36th Street with its sponsor, the Metropolitan Community Church, next to a run-down Best Western hotel. This is where Kimy lives, at least for now.

For transgender teens like Kimy, Sylvia’s is a rare refuge. A quarter of the youth at Sylvia’s are transgender and the atmosphere is safe and caring, although oversubscribed. Exact numbers are hard to come by, however, because no one is really counting. “Good statistics don’t exist,” says Pauline Park, chair of the New York Association for Gender Rights Advocacy. “The relevant government agencies don’t give a damn about transgender people, and that is the simple reality.”

For the last ten years, Park has been lobbying for city and state agencies to track transgender issues, especially among youth. They won’t do it, she says, out of fear of political ramifications. “Many of these agencies are headed by political appointees who say they’re not under legislative mandate to deal with the issue,” she says. “But the real reason is they won’t do it is because they’re political cowards. Transgender kids are out on the streets and it’s a huge problem, but if they did a formal survey, then there would be an argument for doing something about it.”

The last time anyone counted seems to be 2003, when the Empire State Coalition of Youth and Family Services estimated that up to 7,000 of New York City’s homeless youth are queer-identified. If that’s the case, it could be the reason why Sylvia’s Place is so packed, with less than 80 beds throughout the city shelter system designated as “safe beds” for LGBT kids. And even those beds, according to Kate Barnhart, the manager of Sylvia’s Place, aren’t really safe — especially for transgender kids. “There are very few transgender people in the shelter system, because they are not welcomed there,” she says. “But there are lots of transgender homeless people, because it’s fucking impossible to get a job as a transgender person.”

Some shelters have non-discriminatory policies regarding sexual orientation, and in fact, a citywide policy was recently adopted to specifically protect against LGBT discrimination in city-run shelters. But these rules seem to do little to prevent actual harassment. Kate says transgender youth are regularly subjected to beatings and verbal abuse. “In some places, the staff actively participates in the harassment,” she says. “In others, the staff allows the abuse to go on, and just looks the other way.”

New York City’s largest general population youth shelter, Covenant House, has a reputation among shelter workers for being blatantly homophobic. In fact, Covenant regularly rejects so many LGBT kids that the counselors at Sylvia’s refer to former Covenant residents as “refugees.” (The last time Kate did a formal count, she had received 15 refugees in a two-month period, triple the capacity of Sylvia’s ten beds.)

When Kimy was at Covenant a few months ago, she asked the intake counselor whether being transgender would be a problem. “The counselor told me that transgender people are allowed in, but they always cause lots of trouble,” she says. A Covenant House spokesperson categorically refused to comment on allegations that the shelter discriminates against LGBT kids, and also declined to say whether Covenant has a non-discrimination policy or designates beds for LGBT kids.

Even Sylvia’s place, haven that it is at night, bars its doors during the day. Technically, the kids are supposed to be gone by 7:45 a.m., but the counselors do what they can to delay putting the kids back out on the streets.

On Wednesdays, a free medical clinic affords them a few extra hours of sleep, since the volunteer doctor doesn’t arrive at the site until the working day has begun. The kids can sleep in the rectory of the church, where there are chairs and a couple of couches.

This morning Kimy crashes in an armchair, her lanky frame sprawled in the light filtering through the windows of the church. She’s not a morning person, and she rarely gets more than six hours of sleep anyway. Today she’s lucky: the doctor is late due to traffic. When he arrives, he flips on the fluorescent lights and rouses the groggy kids, who are rubbing their eyes and groaning. They shuffle out into the receiving room to wait their turn. Most of them slump into the folding chairs and pull sweatshirt hoods over their faces.

But Kimy can’t get back to sleep. She pilfers through a brown paper bag from the shelter for breakfast: a couple of crackers and a can of apple juice. She pulls a book from her black satchel and reads silently as she waits, tapping her weathered boots on the floor. She hitchhiked from New Mexico to New York City in these shoes.

Two hours later, it is finally Kimy’s turn. The doctor treats her for a mild cold. Kimy doesn’t feel very sick, but her guttural cough has persisted for months, and she thought she should complain about something while she had the chance to get help. “It sucks to get sick in New York City,” she says. The doctor continues to ask questions, her date of birth, whether she identifies as a man or a woman. “I’m a guy,” shrugs Kimy, as if in defeat.

A scale in the corner catches Kimy’s eye, and she begs to stand on it. Appalled to find she’s gained 20 pounds since the last time she weighed herself, she laments having indulged in the “little things” — presumably the meager snacks doled out by the shelter — though her clothes hang limply on limbs that look like toothpicks. Kimy has been hospitalized for eating disorders. She knows she’s not fat — daily, she eats less than one full meal — but nonetheless, the discovery ruins her day. She leaves the church swathed in a black trench coat, even though the day is steadily warming.

Then it’s out onto the streets. Times Square, just a few blocks away, glitters with its usual panache, choked by tourists and Midtown office workers. Kimy merges with the crowds, a full head taller than most, her gait regal, her expression blank. She saunters purposefully, though she doesn’t really have anywhere to go. The day stretches out, endless, nagging. Limitless, and at the same time, stagnant. Her hips, in the pinstriped pants and rhinestone belt she wears every day, swing from side to side, and the heels of her boots click, click, click on the pavement. But from whom to bum the first cigarette of the day?

Turning tricks

Transgender teens face the same problems as the larger transgender population, of whom a disproportionate number are homeless. Many are kicked out of their homes when their parents discover them cross-dressing. Once out on the streets, it’s even tougher to gain and keep a job: Even if transgender people have identification, it often contradicts how they appear. One set of clothes quickly goes ragged, which doesn’t help either. If the kids don’t immediately fall victim to street violence — a looming danger, with society still largely intolerant of ambiguous gender or sexuality — they’re likely to turn to prostitution.

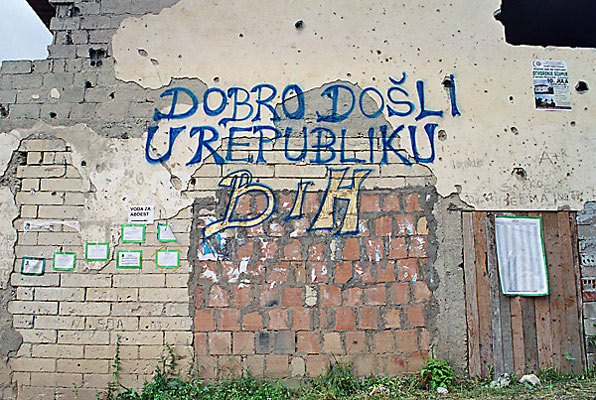

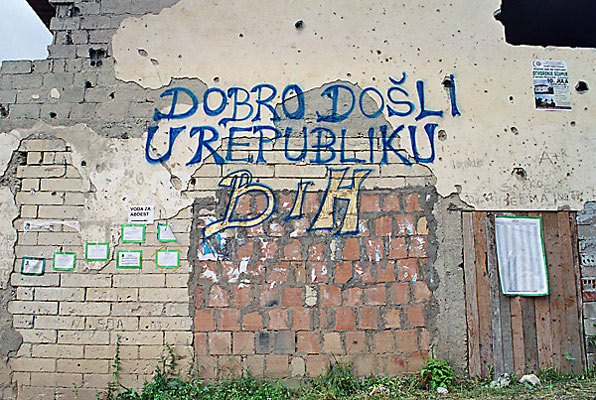

The Easy Internet Café in Times Square has become both a haven from the streets and a thriving social scene for homeless kids in Midtown. Like everything in this city, the scene is vast: The Empire State Coalition has estimated that there may be as many as 20,000 homeless kids in Manhattan alone. Nestled between Madame Tussaud’s and McDonald’s on 42nd Street, at three bucks an hour, the café provides an affordable way to pass the time. Working in groups, the kids can easily bum a few dollars in change, and share the computer time between each other. Plus, it’s warm inside. Although the café’s food counter serves overpriced lattes and pastries, which the kids can’t afford, the smell of espresso and baking bread adds to the feeling of being somewhere “normal,” escaping the drafty chaos of the shelters.

The café also provides a way to make money. Online prostitution doesn’t require an interview or nice clothes.

“The Internet café really has become an addiction for these kids,” says Kate. “It’s a dissociative, escapist thing.” It’s gotten so bad that the counselors at Sylvia’s have started lecturing the kids about “café reduction,” reminding them that they have to go out in the world and get things done if they’re ever going to get out of the shelters. Kate worries about the prostitution she knows is negotiated in the cafés, and tries to encourage phone sex if they’re going to go that route — at least then, the kids are less likely to wind up with an STD, or get assaulted. “But these kids have limited choices,” says Kate, “and I have nothing else to offer as an alternative.”

Usually, Kimy spends several hours a day — however many she can buy — scouring the Internet for potential clients. Back in the small Utah town where she grew up, Kimy made $10 for oral or sometimes anal sex when she first started turning tricks. All that seems a long time ago. Kimy’s parents, whom she describes as educated and intellectual, but “uncomfortable” with her sexual identity, know she’s homeless, but they don’t know she’s turning tricks. Kimy’s too proud to tell them: She doesn’t want to be tempted to take their money. Anyway, here in New York City, she can make more than she used to, because the clientele is often comprised of Manhattan businessmen with money to spare.

But Kimy’s rates haven’t gone up by much. She says she recently made $50 for oral sex with a man in the back room of his office in the Empire State Building, her usual rate for blowjobs. She’ll do full sex for $100, though many of her friends charge twice as much. “It’s pathetic, I know, because everyone else is making hundreds of dollars for the same work,” she admits. “It’s just really easy money.” Sometimes Kimy is selective about her work — not taking offers she feels aren’t worth it — but in times of desperation, she’ll take anything she can get.

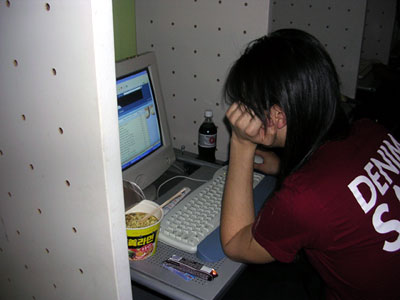

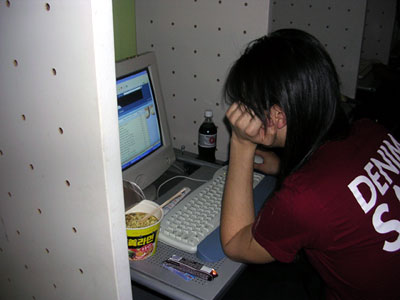

Watching Kimy negotiate online tricks is like watching a mad scientist at work. She typically posts on several different forums, using carefully crafted language to attract clients, and has seven email accounts to handle the massive volume of mail she’ll receive within ten minutes of placing her ads.

Substituting a dollar sign for the letter “S” signals prostitution, and certain words are triggers. “Men like to hear words like soft, warm, young, tight,” Kimy advises. This time, her post reads: “Tall $en$ual Beautiful Young Fre$h Tranny Need$ Financial Help. Can and will do anything. 6’3, 160 pounds. 35, 28, 34 (ouch), slim warm body, long dark soft straight hair. Can do ANYthing. Meow!”

The screen is quickly littered with instant message pop-ups. Kimy responds to each one while simultaneously refreshing her email accounts to read and reply to various offers. She composes flirtatious responses, but her comments aloud — “I hate men,” “losers,” “I hope you all die; I hate you all” — reveal her true feelings.

Kimy says that even if lots of things about being transgender are hard, there’s an upside: It’s easy to find “straight guys” — otherwise known as “tranny chasers” — who’ll pay money to sleep with you. That’s why so many homeless transgender youth end up doing sex work, according to Pauline Park. “There’s a huge underground tranny chaser scene, made up mostly of professional white men,” she says. “Many are married but don’t view sex with a tranny as cheating on their wife because ‘it’s not a real woman.’ They want someone feminine but functional — a chick with a dick.”

Tranny chasers mean fast cash for kids like Kimy, who — while biologically male — puts up a demure, submissive front. And in a strange way, her customers also provide emotional reinforcement. “Male-to-female transsexuals tend to be particularly self-critical,” says Park. “What’s more validating than having a man pay for your femininity?”

But Kimy doesn’t like to talk about things like that, preferring to stick to business. Her bidders are filtered according to their financial prowess. Those who won’t pay enough, she firmly disregards. “This is where it becomes like a business transaction,” she says as she types furiously. “Like trading stocks and bonds.” She induces floods of offers by saying she’s got a “tight asshole” and that sex will hurt her, which isn’t untrue. “They always have to poke around a lot,” she admits. “I have no feelings when it happens. No one can get inside of me. They try and try, but they can’t get in.”

Before Kimy can close any deals, her computer time runs out. None of her friends are around today to bum a few more minutes online. Yesterday, one of the guards kicked them out for being rowdy — the same guard who routinely pays her friends for sexual favors and harasses the group, Kimy says, because he knows they’re homeless. She’s filed a complaint, but so far it hasn’t done any good. Spotting him in the corner, she makes a quick exit before he sees her and makes a scene.

Dress up

All her life, Kimy has wanted to be a girl. She remembers her older sister calling her “Alice” and dressing her in girl’s clothing. At some point, she began wearing those clothes on her own, and she thinks her parents probably suspected she was gay as early as age 4. By age 13, Kimy had abandoned cross-dressing and instead become obsessed with the idea of getting a sex change operation. “I’ve always hated this thing between my legs, and wondered why I have it,” she says. At one point, she was so frustrated that she almost took scissors to her penis and chopped it off.

“Transgender kids who are poor or homeless have little realistic hope of accessing medical care, let alone hormones,” says Shannon Minter, Legal Director for the National Center For Lesbian Rights and board member of the Transgender Law Project. “Street hormones and black-market silicone injections are relatively accessible, but dangerous. But people are in pain, and they’re facing an overwhelming desire to physically transition, so they end up taking desperate measures.”

Even those who aren’t poor may fall into these traps. Most health care plans won’t cover hormones or gender reassignment surgery. Yet surgery — or the stated intent to have it — is one of the factors needed in many states to formally change the gender on one’s I.D. That’s why so-called “pumping parties” — like Tupperware parties, only with silicone injections — have become so common.

Kimy, by the time she was 16, wanted the operation so badly that she started stealing to save up for it. Things were getting worse with her parents, who she says, “just wanted me to be normal.” At first, Kimy just took little things, but eventually she stole computers, cars, and even a cash register. Finally, she got caught.

Kimy was sent to a juvenile detention center for a few months — a place where she says she had never seen “so many penises” in her whole life. There were times when she was almost raped, but she was lucky enough to have some of the other inmates on her side to protect her.

Soon after she got out of jail, she got into a fight with her stepfather. He told her that Utah wasn’t the place for someone like her, that he didn’t want her in the house anymore.

She had nowhere to go. “I just kept thinking to myself if I were a girl, none of this would have ever happened,” recalls Kimy. “I wouldn’t have had to steal things in the first place.”

Kimy took off in a stolen car with a male friend who had fallen in love with her. He told her he wanted to take her away, to take care of her, to never let anyone hurt her again. “We were bouncing, heading east towards Oklahoma,” she says. “He said he had family there that we could stay with.” They got as far as New Mexico before they were both arrested for possession of drugs and car theft. In the local jail, Kimy says, there was a lot of sexual activity going on. An incident — she classifies it somewhere between rape and consensual sex — occurred. Ever since that time, she has hated sex, and men.

When Kimy was released, people on the street told her to get out of their town. She reads tarot cards, and the cards told her to go east. So she began hitchhiking her way to New York City, exchanging sexual favors for rides.

There was a lot of walking, and it was cold. She hit the city in December and spent the first few nights on the streets, crashing on the stairs of the subway entrance where the warm air wafts upward. “The whole time, a stubborn attitude was going through my head, that I could do this,” she says. “I didn’t sleep all night.” Another night she was able to sleep inside Penn Station, where the cops are more lenient. She had $40 in her pocket and a pack of cigarettes.

Kimy decided that during the daytime hours, she should walk around the city and get used to it, get to know it. She didn’t have anything else to do, and she needed to do something. But the winter nights were getting brutal.

She found a phone book and looked up the names of shelters, beginning a phase of constant transition and instability, being bounced from bed to bed. At St. Agnes, the boys flashed their penises at her. At Covenant House, a group of kids beat up her straight friends for hanging out with her. While younger generations on the whole are increasingly tolerant of gays and lesbians, many kids — like the rest of society — still think transsexualism is weird or freakish. The need for LGBT “safe” beds and places like Sylvia’s underscore the threat of violence. Instead of the perpetrators being punished, Kimy and her friends were kicked out. That’s when she came to Sylvia’s Place. She had just turned 19.

A bored and broke tourist

Sometimes, Kimy walks for hours. If she has an appointment to go to, or someone to meet, she’ll often circle the block to kill time. When the weather is bad, she’ll ride the subways. Better to keep moving than to sit still and have time to think.

“Being homeless sucks,” she says. “It’s like being a really bored tourist with no money every single day.” Central Park is a decent hangout, but “there’s a lot of really strange people there.” Often, in the park or along 42nd Street, religious fanatics snarl comments at her, calling her either Jesus or Satan. Wherever she goes, people notice her. But Kimy just wants to remain unseen. “Most days, I just try and hide.”

The New York Public Library is a good hiding place. On cold days, Kimy often reads there for hours in a deserted wing. Plus, the library has free Internet access, even though it’s cut off after half an hour and the connection is agonizingly slow. Kimy heads there now, hoping to close one of her deals.

A few months ago, Kimy had a real job selling newspapers. But she got too much harassment being on the street. One man approached her, saying he wanted her to work as a messenger. It ended up that he just wanted her to be a stripper. She had sex with him for money. “It was disgusting,” she says, as she logs on to the library’s ancient computer with sticky keys. “He wanted to touch my private parts and I hate that, but I had to let him do it.” She lost the newspaper job soon after.

It’s tough to get a job in this city, and even tougher without an I.D. Kimy’s was stolen a few weeks ago by a boyfriend she thought she could trust, and she doesn’t have her birth certificate or proof of address to get a new one. He also took all of her art supplies, her CD player, and what few clothes she had.

Kimy’s just grateful he didn’t take the one thing in the world that means the most to her: her teddy bear, Cubbins. “I’ve had him since I was four years old. He gives me a purpose for living,” she says. “I take care of him. I treat him as the child I’ll never have, even though he’s a stuffed animal. He’s the reason I don’t commit suicide.”

Suddenly, Kimy gets an email offer from a guy who saw her leaving the Internet café. He wants to meet her in ten minutes for a blowjob. Kimy agrees. Hastily, she finishes up the one personal conversation she’s been having — a boy she often talks to online, but has never met. With time running out, she signs off with “I want you to hold me.”

Transformations

Kimy meets her potential trick, a tall man in a business suit, standing outside of the Easy Internet Café. They talk for a while, but eventually Kimy tells him she doesn’t want to go through with the deal. He’s offering her $50, and with the cost of the hotel room where they’d have to go at this hour, she’d only be making $25. She doesn’t want to do the deed for that price. “I would have felt terrible about myself afterward.” With no prospect of Internet use and no money, she bums a smoke and heads to Virgin Records to zone out.

Music is Kimy’s sedative. It is also her source of creative inspiration. Kimy’s dream is to be a fashion designer and have her own studio, where she can create personalized designs for her clientele, who would come to her. Then, she wouldn’t have to go out in public very much. She could stay in her own little world.

When Kimy listens to music, she sees models strutting down runways in her head. She transposes these visions into a black sketchbook she carries with her everywhere. Without her CD player, she now comes to Virgin and hangs out in the trance section. She puts on the bulky black headphones and stands still, letting the sounds wash over her, like a tall, dark phantom, bothering nobody, hoping not to be noticed.

Afterwards, the warm weather allows Kimy to head to Bryant Park to sketch the design she’s just conceived. “I wish I could just videotape what’s in my head and show it to everyone,” she says as she neatly lays out her colored pencils on the small table. She no longer has the luxury of her expensive acrylic paints and brushes, which were among the possessions taken by her boyfriend. She thinks he probably just threw them away.

It’s lunchtime: a chocolate pudding cup and the rest of the crackers from this morning. Kimy draws a black dress with a plunging open back connected by strings of diamonds. The wind billows through her shoulder-length black hair, the afternoon light glinting on the auburn ends of a faded dye job. “Oh yes, this will be really easy to make …” she murmurs. For a moment, she’s somewhere else.

Late afternoon, done with her sketch, Kimy heads to the fashion district to look at fabrics and sewing supplies, things she dreams of buying one day. It’s another one of her escapes. She can spend hours in these stores, surrounded by cotton and silk, fingering the different textures, imagining how well this or that material would work for her latest designs.

Kimy has been drawing for as long as she can remember. “I see things happening in my mind. I want to transform things, and that’s why I’m always really quiet,” she says. “I want to make everything in my head happen in reality.” But fabric isn’t cheap, and Kimy doesn’t have money anyway. So she touches the fabrics delicately, lingering, as if trying to memorize how it feels to hold them in her hands.

Tomorrow, she says, she’s going to be productive. She’s going to go get her food stamps, and maybe try to find a job.

Meat and potatoes

On a Sunday night a few weeks later around dinnertime, Sylvia’s place is quiet and empty. It’s warm and smells of cooking. Some of the kids are next door attending church services. Others won’t arrive until the midnight curfew. Kate stands at the kitchen countertop elbow-deep in ground beef. The kids sometimes help out with the cooking, but the duty mostly falls to Kate and the overnight counselors. Flour dust coats her green housedress as she prepares the meat and sets it to bake in the oven. Then she scrubs a dozen potatoes and seasons them with salt and pepper.

Meals here are usually simple. The kids are always hungry, and they’ll eat pretty much anything. Sometimes, Kate treats them to her special pot roast. One of the counselors, Frederick, is rumored to cook the best homemade macaroni and cheese in town. Even the gaunt, wiry Alicia, a transgender resident, says she’s put on 10 pounds by eating Frederick’s food. Usually, though, dinner comes courtesy of the food bank, and that means meat and potatoes.

A kid comes knocking at the gated entrance, begging to be let in. “It’s not opening time yet, Ron. You know that,” Kate reprimands. Ron says he’ll clean and do chores if she’ll let him in. It’s cold outside. Finally, Kate relents. “Oh, alright. I don’t believe you, but alright,” she grumbles, unlocking the gate. Ron, a kid with bleached hair and tattoos, bounds inside like an overeager puppy, his wallet chains jingling loudly. He sits down next to the table where food is laid out for the weekly church social and starts picking at the Saran Wrap. “I’m just fixing it!” he explains when Kate tells him not to touch. But he stays there, staring at the food, as she washes the dishes.

Kate sees lots of turnover, but lots of kids end up coming back to Sylvia’s. Many youth create their own little families on the streets or in the shelters after being kicked out of their homes. “There is a huge amount of resilience among these kids, but they do end up adopting a homeless mentality,” says Kate. “All of their friends are homeless; their identity becomes homeless. They end up being lonely when they get housing.”

An hour later, church is out and the shelter is filled with people. They stand around socializing, holding plastic plates full of grapes and sponge cake and leaning against the file cabinets labeled with names where the kids keep their clothes and any belongings.

In a few hours, this space will be filled with metal cots, the blare of a large television, and kids passed out under piles of blankets, trying to sleep away the day. In the midst of the festivities, a quiet teenager in a too-large coat comes knocking at the door. Someone lets him in and finds Kate, who takes him aside and starts writing down his information. The shelter’s ten beds are full, but he doesn’t have anywhere else to go.

Teenagers like the new arrival gravitate towards Kate. They seem to know that she cares. A decade of work in the New York City shelter system has gained her a reputation among queer-identified homeless kids because those who welcome them are so rare. “Rape is pretty common among these kids,” says Kate. “So is post-traumatic stress disorder. There’s also the depression that results from being part of a marginalized community, a sense of limited opportunities. The only visible transgender people right now are either performers or prostitutes.”

For kids like these, Sylvia’s is a haven. Kate watches them move in and out of the iron gate and sees their sadness and pain. “There’s a concept in Judaism, Tikkun Olan,” she explains. “It’s as if there is a glass sphere, a globe, that has been dropped on the floor and shattered into a million pieces. We each pick up little pieces of glass, and slowly put the world back together.”

It’s nearly curfew, and the churchgoers have gone home. Kids lounge on the cots watching television, and Frederick is doing the dishes. Kate sits at a table doing paperwork.

Kimy steps outside for one last cigarette before bedtime. She’s wearing flannel pajama pants and clutching Cubbins. Her hair, wet from the shower, falls in its natural waves against her shoulders. She laughs, recalling a conversation she had earlier this evening with Kate, when they were discussing what it would be like if people had tails. They imagined some people would cut their tail-hair into fashionable styles, some might dye it odd colors, while others might let it grow long and bushy. It was a good moment and those are rare.

Kimy takes a drag on her cigarette and says, “I feel like I’m in a pit right now. I can’t get an I.D. because I can’t get my birth certificate. I can’t get a job.” To make matters worse, as she was walking down the street this afternoon, a man leaned out of his car window and yelled, “Whore!” at her. She tried to ignore him, but it hurt. She called her parents crying a couple of times, but was too proud to take the cash they offered.

It’s time to go in. “I feel stuffed,” Kimy says, putting out her cigarette. “Like someone has sewn me Victorian-style into this body, and I’m wearing a big coat, and I just want to shed it, and I can’t.” Tomorrow she’ll begin again. She’s heard of another modeling agency, one that might be interested in her look. She’s heard they don’t require pictures.

An update: Kimy finally got her birth certificate. She was hired at Banana Republic, and started interning for a fashion designer on the side. She saved up enough cash for a room in Harlem. But when she kept showing up for work late, she was fired. Unable to make rent, Kimy has started turning tricks again, crashing at Sylvia’s or in the apartments of the men who hire her. She’s trying to save up for a bus ticket to Montreal, where she thinks she might have friends.

Erin Marie Daly

Dear Reader,

In The Fray is a nonprofit staffed by volunteers. If you liked this piece, could you

please donate $10? If you want to help, you can also: