Raphael Cohen-Almagor is a is a world-renowned political scientist (D. Phil., Oxford) who published dozens of books and articles on education, free expression, media ethics, medical ethics, multiculturalism, Israeli democracy and political extremism. An organizer of the international “Gaza First” campaign, a campaign for the withdrawal of Israeli settlers and soldiers from Palestinian territories beginning with the Gaza Strip, he was the founder and director of the Center for Democratic Studies at the University of Haifa. At a peace education conference in Turkey, Cohen-Almagor discussed with ITF contributor Aditi Bhaduri his disenchantment with Israeli politics, the Middle East peace process, and what motivated him to establish the Center for Democratic Studies.

The interviewer: Aditi Bhaduri

The interviewee: Raphael Cohen–Almagor

You founded the Center for Democratic Studies at the University of Haifa. What inspired you to do that?

[T]he idea for the institute came up on November 5, 1995, the day after the assassination of Yitzhak Rabin. I was one of those who saw the writing on the wall — and I warned against political assasination. I was teaching then at the University of Haifa, at the Faculty of Law and Department of Communication. When Rabin was murdered, this was not a shock to the mind, but a shock to the heart. I started thinking, what could I do to help the decision-making process — as a scholar? Realizing that there is a large gap between Israel as a democracy and the public that does not understand what democracy is all about, I decided to establish a center designed for the study of democracy and its underlying values:liberty, tolerance, equality and justice. These values are clear to students in United States or in England. I ask students what … liberal democracy is, and they will give me a detailed answer in ten minutes. In Israel, however, the discussion may last an hour until a full answer is provided. The center serves as a meeting point for people from all walks of life: Christians, Muslims, Jews — those who are religious and those who are not. It is a platform for discussion; of pluralism, of tolerance, of mutual recognition. For the past four years since the founding of the center in , what I tried to do is promote awareness, in Israel and outside the country, of democratic virtues, to promote justice, pluralism, multiculturalism, freedom, peace. People at the center do this through seminars, conferences, education. My dream is that the Israel Ministry of Education will [embrace] democratic studies … and introduce these studies into the curriculum both at the primary schools as well as at high schools. Presently, there are no studies on democracy in Israel — and there should be.

What are the challenges to Israeli democracy?

Israel, being the only Jewish democracy in the world, suffers from intricate symbiosis: we would like to be Jewish and we would like to be democratic. But when you look at the values that underline these two concepts — Judaism and liberal democracy — they are difficult to be reconciled with each other because the first premise of liberalism is to put the individual at the center of attention:, everything stems from the individual and returns to him or her … you allow the individual maximum rights … to develop to his or her fullest potential so long as [he or she] does not harm others. [C]onsequently, the individual will contribute to the development of society. But in Judaism, the belief is that you owe your freedom to God, and you owe an explanation about your life to God. There is no autonomous freedom. Freedom is given to you to serve God and His aims. Now, the zealots within Judaism (this is just a fraction of Judaism) believe that we are all sailing in the same boat, and if there are secular people like me in that boat, who follow the maxim “live and let live,” we will make holes in the boat, and we all sink down to [the bottom of] the ocean. So, they cannot let me live by that maxim. Therefore, coercion is going to be used to make me toe that line.

Israel is a secular country. The religious people make [up] 20 to 25 percent of the population. Still, Israel is following Jewish law, Jewish values and norms are infiltrating every aspect of one’s life as an individual. In the most private issues of your life, religion interferes even though Israel is a secular state, and this creates a tension between Judaism, on one hand, and liberal democracy, on the other. That's a major problem that we have to address.

The other major problem is our relations with the Arabs — the Palestinians living inside Israel — which constitute about 20 percent of the population, about one million people. They don't believe in the raison d'etre of a Zionist state. They are in Israel because their forefathers were born there, they were born there, and for them Israel is actually Palestine. And this, of course, creates tension and problems.

And then we have Palestinians outside of Israel — some of them Hamas who don't recognize Israel, don't recognize Israel's right to exist, and believe that I should return to Bulgaria (that's where my family came from) or preferably I should drown in the sea. They don't recognize me, [which makes it nearly impossible for us to have a discussion.] … So as long as there is terrorism and as long as there is war between us and Palestinians, then this … creates a major challenge for Israeli democracy.

Israel is a society under stress, where security plays a considerable role in its daily life. In a liberal democracy, you have to invest in the people, in the individual worker, health, education, etc., and that's difficult to do so when security consumes 30 percent of your budget … there's not much left for other purposes.

Given the current international scenario, where religion is playing an increasingly larger role, do you think it will be easy for Israel to sever completely religion from state?

Israel is a secular country. There is a lack of separation of religion from state, but but I don’t think that is because of the rise of religion in world politics. Separation between state and religion is an Israeli decision in Israel’s interest, but you need a courageous leader to take that decision. Right now, because of narrow political interests, and the fact that all governments in Israel were coalition governments, most of them included a religious component, those in power were afraid to take a drastic step and and separate religion from state. This was the only consideration.

I believe that it’s better to separate religion from politics, but unfortunately the religious parties believe otherwise. … Anyway, we live in separate communities — we don’t eat together, we don’t live together, we don’t study together. So [why] does it bother them if I want to have a civil marriage? [B]y making this an issue, … I think it weakens them because all it does is create alienation. People don’t like to be coerced. True, the majority of Israelis don’t care so much about these issues, but a significant part of us does. The state is there to cater for the interest of 100 percent of the population, not just the 70 or 80 percent. There should be more freedom for people to lead their lives the way they want to.

So what do you think the solution is [for] the conflict over Israel and Palestine?

Unfortunately, peace is not something that you can do alone. It’s like dancing the tango alone — you need two to tango. From 1993 onwards, the Rabin government, the Barak government, and the Sharon government were willing to take significant steps to build an independent Palestinian state. What we got in return was terrorism. We did not get any reciprocal recognition of Israel, of our needs or interest[s], and a willingness to create a two-state solution from the Palestinians.

When this is the [situation], there is not much we can do. My hope is that the Palestinians realize that Israel is here to stay, that the two-state solution is the only way out of the impasse. Not one state called Palestine at the expense of Israel, but a two-state solution, meaning deserting what Hamas is upholding now, and instead going through reconciliation steps and accommodation of [each] other [so] we will have a partner to talk to. And then I am sure that the Israeli government will be willing to take the necessary steps to build upon trust between the two nations and build a Palestinian state. But we cannot do it alone, and we cannot subject ourselves to Qassem rockets. Would India allow daily rockets and missiles to fly from Pakistan and hit Kolkata, New Delhi, and other Indian cities daily? No, there will immediately be war.

You began a “Gaza First” campaign. Tell me about how it started and what it is.

In 2000, I began an international campaign for “Gaza First.” I nagged the government, wrote letters to all parties, to the prime minister, and also campaigned outside of Israel in every place I could.

The plan was adopted by Sharon in 2003 and implemented in 2005. I campaigned for Gaza first, meaning this was the first step towards reconciliation between the two sides, and then [we were supposed to give up] the West Bank, when, in return, we got Hamas and the Qassams, we [cannot] proceed further. Israel is a very small country … it’s only 40 kilometers between East and West and all the major cities, including Tel Aviv, Jerusalem, will be easily covered by Qassams from the West Bank. Therefore, no sane prime minister can do that because this is suicidal. Great opportunity is lost. The Palestinians have one of the most dovish government[s] in the country's history. Minister of Defense Amir Peretz has been working for peace all his life.

What do you think of Israel's recent war with Lebanon? How will that affect politics in Israel?

Again, almost from the beginning I said this was insane. Prime Minister Olmert made a mistake — the government went into war without realizing that it was opening war. I call it the “Hezbollah War.” This unnecessary war was a big blunder and Olmert is going to pay a big price for that. The Israeli public will not forgive him [for] this misconduct. Observing how the events unfolded, the Hezbollah did a nasty thing: they kidnapped two soldiers and killed eight. Now what’s the way to retaliate? First of all I think, take your time and ponder. [That] doesn’t mean you won’t have to do anything. But the retaliation came within 24 hours [with] the bombing of Southern Lebanon and … the capital city of an Arab state, Southern Beirut. Now, if Olmert knew that the Hezbollah [was] going to answer by non-stop rockets on the North of Israel, then he made a tragic mistake. And if he didn't know, then again he made a tragic mistake. If you are going to such a war, then you have to prepare the North for the barrage of rockets that might come in and out on a daily basis.

There is a growing movement in Israel calling for elections and calling for Olmert, Amir Peretz and Chief of Staff Dan Halutz to resign because of this costly mistake. Some 160 people were killed and hundreds were wounded. I believe that this public voice will gain momentum, and that ultimately Olmert will be forced to resign or to call upon elections.

[Chief of Staff Halutz had resigned since the time of the interview. A.B.]

And what is your prognosis?

Well, I am not a prophet, but we may envisage the following scenario: there will be three leading contenders fighting for elections. One is Olmert, head of Kadima, [the political party] founded by Sharon. Next is Bibi Netanyahu of Likud, and third is Labour. Within [the] Labour [party], I presume Peretz is going to face severe challenges. One of the leading contenders is Ami Ayalon, who was the admiral in charge of the navy. He is calculating his deeds in a sensitive and political way, and might be able to challenge Amir Peretz and to take over. So at the end of the day, we may have Ayalon, Olmert, and Netanyahu. At this stage, Bibi Netanyahu is leading in the polls, but the polls are not real elections. Anyway, we do not know yet when elections will take place. According to [the] official timetable, it should be within three-and-a-half years. I can't believe that this government will survive more than a year. It may collapse any day.

Aditi Bhaduri

Dear Reader,

In The Fray is a nonprofit staffed by volunteers. If you liked this piece, could you

please donate $10? If you want to help, you can also:

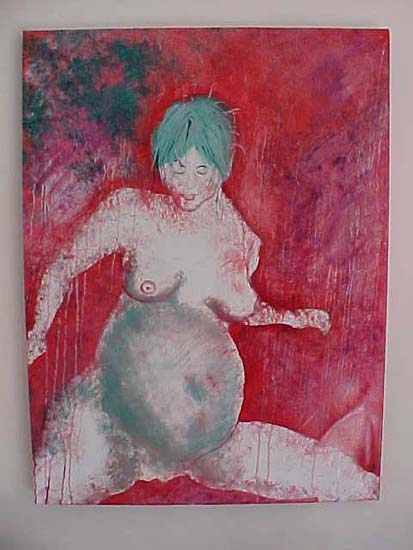

Why eating for two can make a woman think twice about her body image.

Why eating for two can make a woman think twice about her body image.

When battling obesity means fighting the body you’re born with.

When battling obesity means fighting the body you’re born with.

Wally Lamb’s She’s Come Undone explores the dark corners of obesity.

Wally Lamb’s She’s Come Undone explores the dark corners of obesity.

Attack of the junk bulge.

Attack of the junk bulge.

Sudden weight loss doesn’t make life as a woman any less heavy.

Sudden weight loss doesn’t make life as a woman any less heavy.

Images inside abandoned Catskills resorts.

Images inside abandoned Catskills resorts.

A conversation with Raphael Cohen-Almagor on the prospects for Israeli peace.

A conversation with Raphael Cohen-Almagor on the prospects for Israeli peace.