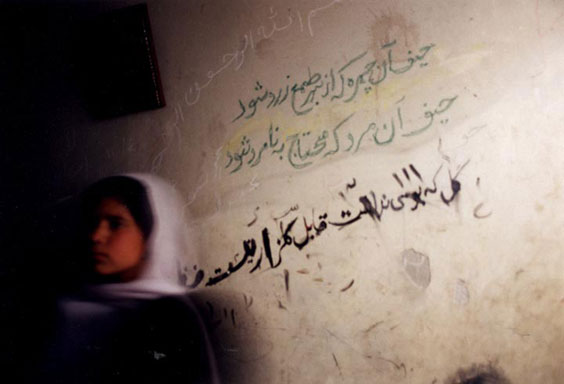

One of the first female faculty members at the resurrected education university in Kabul, Afghanistan, rummaged through her desk in the office of the English department, a narrow room with a single window.

We had just spent the morning with her, observing her colleague as he taught an English class. She said she had something to show us, a gift from her students. But after opening and slamming metal drawers shut, she sighed. She couldn’t find the photograph she was looking for, so she described it to us: Some of the male students had found a broken stair railing with vertical metal bars. They all held it up to their faces like they were in prison, and posed with exaggerated expressions of misery. One of them displayed a handmade sign: “Guantanamo University.”

“That was my gift,” the young professor said, rolling her eyes like an exasperated mother. I felt a stab of shame in my country’s government.

And now the Americans

If we are to believe the American point of view, the recent history of Afghanistan could be divided into pre- and post-Taliban, one of the world’s most infamous theocracies.

The Taliban years, from the mid-1990s until the U.S.-led overthrow after September 11th, seem to us a nightmare of medieval proportions: adulterers and thieves stoned and hanged in public, ancient Buddha statues destroyed, burqa-clad women beaten with sticks for showing an ankle or for wearing fingernail polish, music and kite-flying prohibited.

We Americans were all too eager to portray post-Taliban life as an explosion of long-denied freedoms. Women threw off their burqas and went to beauty parlors. Girls returned to school. Kites, pop music, and Bollywood flicks filled the skies, airwaves, and cinemas, and the newly installed Democratic government and constitution would soon usher in a new era of hope and modernization.

Of course, now we know the liberation of Afghanistan has proven more complex.

Nearly seven years after the U.S.-backed Northern Alliance made its triumphant entry into Kabul, President Hamid Karzai and NATO struggle to keep even Kabul under their control. The Taliban have regained control over much of the south and the volatile regions along the Pakistani border. Regional leaders — many of them affiliated with the Northern Alliance, which fueled the brutal civil war that preceded the Taliban — govern with equally draconian restrictions on women. In many provinces, local villages have chosen to side with the re-emerged Taliban over NATO and the new government; they reason that at least life was orderly, free of suicide bombings and rampant opium trafficking, under the old regime.

Four years ago, when I visited Afghanistan with photojournalist Stephanie Yao, I was struck to discover that nearly all the Afghans I met saw the United States as just another foreign occupier. (The Taliban originated in Pakistan.)

“First we had the British,” a longtime Kabul resident, a woman of about 60, told me. “And then the Soviets. And then the Americans came in to fight the Soviets. Then the mujahedin [the anti-Communist resistance fighters who started a civil war after the Soviets left]. After that, the Taliban. And now the Americans again. We’ll see if they do any better than the others. Probably not.”

Meeting the English professors

I recall first meeting the woman I shall call Fahima by accident, as my group and I were being escorted from one dull official meeting to another. At a teacher-training college, streams of students whisked past us. The young women and young men never mixed, but they wore modern clothes, by Kabul standards. The men wore jeans and western-style button-down shirts in bright solids and plaids. The women were in trim two-piece ankle-length skirt sets and modern headscarves that were close-fitting, not the voluminous shawl-like ones most other women in Kabul wore. I felt disconnected from them; I wanted to know them and their lives, but they glided past us like fish in an aquarium.

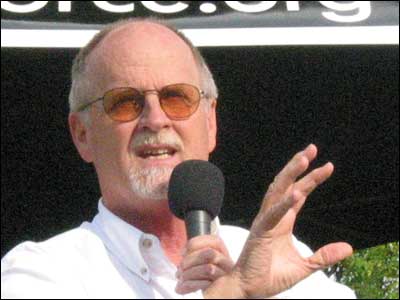

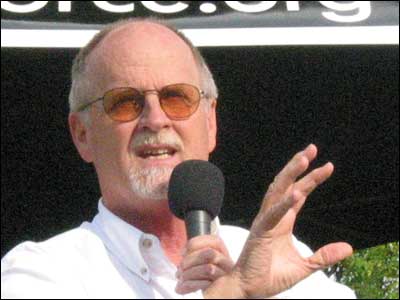

I cannot remember why Fahima was different, how we managed to stop and talk to her and Hamid (also a pseudonym) — both young professors in their late 20s. Maybe they overheard us speaking English to each other and said something to us, or maybe we heard them talking in English. I do recall making eye contact with her, and being drawn by her lively, dark eyes. She was surrounded by men, her male colleague and three male students; mixed-gender groups were unusual. She was tall, taller than some of the men, and her tailored gray skirt and top seemed to accentuate this. She told us they were all professors and students in the English department, and that now, particularly since the American invasion, this was the “hot” major.

Russian used to be the sought-after major, she said. Once there were hundreds of Russian majors at the university, and now there were about a dozen. The Soviets were yesterday’s occupier. Now everyone, from the United Nations, to construction companies, to journalists, were willing to pay top dollar to English-speaking, trustworthy Afghan workers, interpreters, or fixers. The students flanking her puffed up with pride as she talked about how only top applicants were accepted into the department.

“Will you come visit us in our department later?” Fahima asked, as our escort from the dean’s office started shifting from one foot to the other. We had another meeting to get to. We agreed to come by later.

Waiting for the grass to grow

“Come in, come in,” our two new professor friends beckoned us into the office, which had two proper desks, and several haphazardly arranged student desks, the kind with the chair attached. Hamid rushed around to arrange the student desks into a comfortable configuration for us. Then, to be official, or perhaps because it was the only space left for them, each of them took their seats behind their two desks.

Their desks, jammed together, took up nearly the entire length of the room. The female professor had to walk all the way around her colleague’s desk, a breezy sweep of gray fabric and trim white headscarf, and work her way into her desk, which was closer to the door. He took his place after her, easing into his. The ease with which they did this, the proximity of their desks, spoke of an intimacy that defied their propriety. Of course, we never saw them once touch, and they never held eye contact with each other for more than a second — even that would have been considered brazen outside of this liberal university campus. But their fondness for each other occupied the little air in the room. We settled into our seats, talking about all manner of things.

Fahima told us about her ill-timed entry into teaching. After her education was interrupted several times by the civil war, she finally graduated and was hired by the college. The year was 1995. Unfortunately, she barely finished a year before the Taliban took control of the city and banned female teachers and students.

“I spent five years at home. I read my books and dictionaries as much as I could,” she said, her English accented and precise. Some of her female students came to her family’s home, where their professor secretly tutored them. But as the Taliban became increasingly extreme, she feared what would happen to her if she got caught — and her anxious students stopped coming. “All I wished I could do was stand in class one day and teach my students. I prayed for it.”

The college was one of the few in Afghanistan that had close to a 50-50 male-female student ratio in 2004, but a female professor was in the distinct minority. Women comprised only 15 percent of university faculty in the country. Fahima knew how important she was to her female students.

“They sew clothes for me,” she said, motioning to the sleek gray outfit she wore — a sort of Muslim-friendly skirt suit, with a slightly fitted button-up top and a long, flowing skirt. These gifts from students were welcome, she said, given that the cash-strapped university couldn’t afford to pay her a living wage. The young women had a special bond with her, she admitted, often seeking her out for personal advice.

“I hope when my female students see me, they know what is possible for them.”

Then, realizing she had been talking about herself for a while, she turned to her male colleague, who had been listening attentively. “Well, what about you? Let’s hear about your stories.”

He waved her off, shaking his head. “I have no good stories,” he said. “Only yours are good.”

All of us women cajoled him until he offered that he loved soccer. “I was a footballer,” he said.

“Was?” I asked.

“Before the Taliban, he was a very good player,” Fahima said. “He played for a professional team.”

His easy smile became broader as he lowered his head sheepishly. He said he had not played seriously for years. Though he wore a baggy button-up shirt and jeans, I could see the strength of his legs in the way he stood, feet slightly apart as if ready to defend the goal, and the athleticism in the broadness of his slightly squat torso. But of course, I was not supposed to be noticing these things. Away from the relative freedom and permissiveness of the college campus, our Afghan American interpreter had laid out the rules clearly for me: No eye contact with men.

Not eager to get in any kind of trouble, I took her lead and got used to studying the carpet or some other focal point on a wall as I talked to men. But here, on campus, I immediately sensed the slack in the rein. I found myself using the additional freedom I had to study men in subtle ways, noticing all the things that even a light gaze now and then could pick up. Even our interpreter, thoroughly accustomed to both Afghan and American ways of being, reacted to it.

“He has pretty eyes,” she whispered to me at one point on campus, out of either professor’s earshot. I nodded immediately, having noticed his heavy-lidded, golden-hazel eyes as well, so often crinkled in a smile. Of course, Fahima, who worked with him day in and day out, could not have been blind to this either.

“But of course, it’s quite a miracle he can play football — soccer — so well,” she continued the discussion, a glint in her almost-black, almond-shaped eyes, “since he is so short.”

Her laughter came musical and easy, and he let out an open-mouthed gasp in mock offense. He feigned indignation, but couldn’t stop the smile from creeping up on his face. Clearly this was a running joke between them. She was one of the tallest Afghan women we met in our time there, her lithe frame appearing to stand an inch or two higher than her colleague’s with her heeled shoes on.

I wanted to know more about his competitive soccer days, so I asked. That was more than a decade ago, he said, and seemed at a loss to describe a time so far removed. I pressed on a bit. “What were the games like? Whom did you play? What did your uniforms look like?”

His expression clouded. “The Taliban didn’t like us wearing shorts. When we played in Kandahar, the Taliban shaved our heads and imprisoned us for two days. Our hair was too long and our beards too short. Soon, we just stopped playing. There wasn’t really space for football.”

Much has been made of the Taliban’s conversion of Kabul’s soccer arenas into public execution sites, like modern-day coliseums for the aforementioned hangings and stonings. But I knew this was not what he meant. Space was in the mind and heart; the capacity to relish sport that was subsumed first by the civil war and then by the Taliban’s harsh rule, and the poverty that overtook the city during both eras.

He grew quiet. I tried to shift to a brighter perspective.

“Well, now that the Taliban are gone, are you playing again?”

The professor raised his eyebrows, as if he had never really contemplated the idea, even though nearly three years had passed since the overthrow. Everyone in Kabul seemed so busy, so frantic to catch up with the sudden new world order — going back to school, learning English, angling for lucrative contractor jobs. Soccer seemed frivolous.

“No. Maybe someday I will,” he said. He turned to the window, as if trying to see through the university walls to the brown rubble and dirt roads outside. “Someday when grass grows in this place.”

Liberation in the classroom?

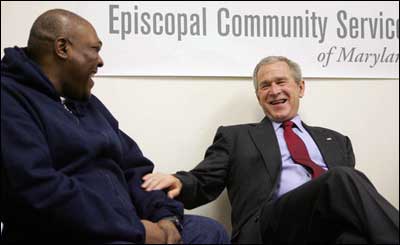

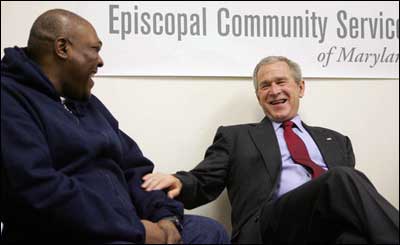

Later that afternoon, Fahima sat with us as we observed Hamid teaching his English III class. The students were working on identifying subjects, verbs, and objects in sentences. Their professor was encouraging them to come up to the white board to write sentences and then underline the subjects, verbs, and objects in different-colored dry-erase markers. It reminded me of the sentence-diagramming exercises I so dreaded in middle school English.

The male students were eager, their hands shooting up at every opportunity. But the women’s hands remained firmly on their desks or in their laps, and they avoided eye contact with their teacher. One broad-shouldered male student, wearing a snug-fitting white polo shirt, went up to the board twice. The second time, he wrote “I like to swim” in large letters, skewed at a strange angle because of his somewhat forced stance. Our interpreter laughed and whispered to me that he seemed to be flexing his muscles as he wrote. There was no mistaking it; that was exactly what he was doing. The telltale arms-akimbo stance and exaggerated motions, uncapping and recapping the different-colored pens — some male behaviors are universal, apparently.

The professor finally called on Lima, a petite, pale girl in a light-brown outfit and cream-colored headscarf. Fahima whispered that Lima was a top student, much better than the boys who had gone up before her. Lima stared at her shoes as she walked quickly up to the board, snatched a pen, and wrote her sentence in small, timid handwriting. She bit her lower lip as she found each of the colored markers, underlining words as if this all couldn’t end soon enough. It was the best, most complex sentence that had been written, with conditional tense and dependent clauses.

“Very good. Excellent,” her professor encouraged her.

She slunk back to her desk quickly, with a slight smile on her face.

I knew it was easy to exaggerate in our minds the significance of that moment. The idealistic, feminist, American part of me wanted to think that something revolutionary had happened. That little by little, each woman student the professor coaxed to the front of the room was changing Afghanistan. That somehow, that turn up at the board incrementally altered each woman.

But when I talked to some of the female students later, I learned that many of them doubted they would pursue careers after their education. Their parents would resist any job that would require living away from home, thus limiting their options. Even jobs in the city would be difficult to get to, since few had their own transportation. There were still few female drivers on the road, despite the lifting of Taliban restrictions on women driving. And they were expected to marry soon, with no guarantee their husband and in-laws would approve of them working.

Fahima admitted she was a rarity — a woman of nearly 30, whose father was comfortable with her pursuing a career and remaining single, for now. Her father was disgusted by families — particularly uneducated rural ones, she said — who married their daughters off as young as eight years old in order to benefit financially from the arrangement.

Ultimately, the shortsightedness brought on by poverty would likely be the worst enemies of her female students’ budding careers. Though a bilingual woman working or teaching for an non-governmental organization, or interpreting for the United Nations, would make good money for her family, many parents pushed their daughters to marry early for economic reasons. Not only would the bridewealth paid by the husband’s family provide much-needed cash, but marrying off a daughter would also mean one less mouth to feed.

An educated daughter might catch the eye of a more affluent family’s son, and she might be better taken care of with her in-laws than with her parents. The students at the college were from middle-class families for the most part. But in Afghanistan, to be middle class is still a struggle. In reality, the economic exchange system of marriage had been in effect for centuries, millennia even. In harsh times, that could be relied on. The whispered promise of education and employment for Afghan women felt alien and unreliable in these times.

Still, I engraved Lima’s slight, self-satisfied smile in my memory. I wanted to remember it, for what it was worth.

Fahima who was sitting in the corner of the room with us, suddenly had a gleam in her eye. She smiled and stage-whispered to us as the teacher walked toward the front of the room: “Maybe we should lower the board, because now Hamid is going to write something.”

We stifled our giggles. The class seemed unfazed and unaware. Hamid stopped for a moment and glared at Fahima. But then his stern look broke into a smile, and he shook his head. Barely missing a beat, he grabbed a marker and began writing the homework assignment on the board.

After the class, alone with Fahima in the cramped English department office, we teased her about her colleage. She raised her dark brows in an exaggerated gesture of surprise, shook her head fiercely, and then furrowed her brows to say, “No, no, no. We are just friends and colleagues.” Her English was, as always, crisp and formal, but I could detect the hint of a chuckle behind her declaration.

Graduation

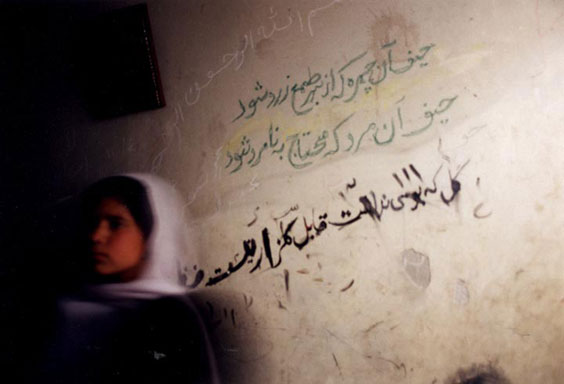

Later that week, we went with our two new professor friends to the school’s graduation ceremony — the first for the three-year program since the Taliban’s overthrow. The women who received their diplomas that day, in a local restaurant banquet room, were the first female university graduates in a decade. The occasion was festive, beginning with a reading of Quran verses, and ending with a live band that alternated between deafening Persian synth-pop and Pashtun folk music.

Young women in colorful, sparkly outfits and headscarves posed for pictures with their proud parents. They sat talking to each other and fingering their colorful pink-and-turquoise diplomas, while the boys danced with abandon. The women feigned a lack of interest in the young men taking turns on the dance floor, twirling, clapping, and writhing until their faces glistened with sweat. Fahima told me the women would dance later, when the men finished.

In America

After our visit to Afghanistan, I learned that our professor friends would be coming to the University of Indiana. I lost contact with them, but I couldn’t help wondering if the time they spent traveling together may have caused love to flower.

As Afghanistan’s fragile post-Taliban hope fractured into dwindling U.S. and NATO control, suicide bombings, and growing daily death tolls, I felt that wish was hopelessly romantic. Did I expect the two of them to taste American freedom, fall rapturously into each other’s arms, then return to Afghanistan and, by the sheer force of their love and determination, save all the college-aged women? I wanted a Hollywood ending — just as we Americans had envisioned fixing Afghanistan as a matter of casting off the Taliban like a burqa, as the sunshine of freedom heralded a new day.

If I learned anything from my time in Afghanistan, it was that only Americans, not Afghans, saw the overthrow of the Taliban as a defining “before and after” moment. For most, the near quarter-century of war and unrest that had preceded 2001 — the endlessly changing regimes, each one brutal and ineffective in its own way — had numbed them from investing too much importance in the end of a theocracy and the beginnings of a U.S.-installed democracy.

But it was the final twist in this story that delighted me with the surprise of discovering lost friends, and blindsided me with the realities of the threatening, lawless place this so-called democracy has become.

When the original version of this piece was posted online, I immediately heard from the young man I am calling Hamid for the first time in years. He and his female colleague were indeed at the

But their dreams came with a price back home. Fahima’s family had been threatened because she had gone away to study at a

I had read news accounts of this growing climate of fear, the threat of an unseen but ever-tangible form of vigilantism that pervaded Afghan life now. Four young actors from the Hollywood movie The Kite Runner were relocated to the

I apologized to my worried friend, but he interrupted me with his own apology. We had so much fun when you came and interviewed us, he said.

“It’s not at all like it was then. We all felt free to talk to you,” he said, his voice heavy. “

- Follow us on Twitter: @inthefray

- Comment on stories or like us on Facebook

- Subscribe to our free email newsletter

- Send us your writing, photography, or artwork

- Republish our Creative Commons-licensed content