- Follow us on Twitter: @inthefray

- Comment on stories or like us on Facebook

- Subscribe to our free email newsletter

- Send us your writing, photography, or artwork

- Republish our Creative Commons-licensed content

There’s no denying it — those iPods and their ubiquitous white earphones have had a strong influence on the business, entertainment, technical, and cultural landscape many of us grew up knowing. The adventure of the innovative iPod, from conception to consumer, is an exciting and enlightening story, chronicled by Steven Levy, senior editor and chief technology correspondent for Newsweek, in his book The Perfect Thing: How the iPod Shuffles Commerce, Culture, and Coolness.

Levy explores the impact of these personal digital music players on the music industry and on Apple Inc. He also delves into the idea of cool (namely, what is “cool” and how does an object get to be cool) and culture (what does it mean when we all “check out” with earphones). Levy’s affection for the object is clear — even to the point of writing each chapter as a standalone, enabling a shuffle of the book’s content in true iPod fashion, replicating the gadget’s feature that plays loaded songs in random order.

Levy’s fascinating inside look at how the iPod came to be is richer because of Apple’s cooperation with the project. The book includes numerous interviews with the people who made the iPod possible, including forerunners like Michael Robertson, the proprietor of MP3.com, one of the first efforts at legally selling music online. By covering how revolutionary the iPod was to the music industry (now selling individual songs a la carte instead of tied to albums only) and Apple (guiding the computer-maker’s foray into iPod-maker and then music-seller through iTunes), Levy sets the stage for turning the reader’s eye from the commercial to the cultural implications of the iPod.

Does putting on the white iPod earphones equate with tuning out and withdrawing from the world, or to being a more active listener? Levy’s book demonstrates that these are questions that have been asked since the dawn of the personal music device. Since 1972, when Andreas Pavel hooked up open-air headphones to a Sony cassette player, the implications of aural withdrawal from the surrounding world have been discussed, as the Sony Walkman took hold, then MP3 players in general, and the iPod in particular.

Levy presents both sides of the argument: that people are missing out on social connections versus fully enjoying their music by focusing on it. He builds on the idea of proactive enjoyment of music by citing that iPod users are now free of the restraints once placed on them by artist or record label limits via albums and CDs. The shuffle feature means the locked-in order of CD tracks no longer governs listening; the ability to buy songs individually from iTunes frees listeners from having to buy whole CDs when they want only one or two songs.

Levy further demonstrates this consumer-centric entertainment model by discussing the evolution of the podcast — digital media files, usually audio — that are distributed by syndication feeds and played on personal media devices like the iPod. No longer do people have to hope there’s something appealing being offered by a media company of any kind. People can make it themselves and get it out there via RSS feed. Plug in your iPod and download your podcasts for easy listening on your own schedule. Like zines and blogs before it, iPods make content delivery easier, another development in DIY (do-it-yourself) culture, leveling the cultural playing field and offering niche-creators access to a broader audience than they might have otherwise had.

This freedom — to enjoy your personal music library and digital files when, where, and how you like — is the crux of Levy’s examination of the ideas of culture and the iPod.

The Perfect Thing is a compact yet broad view of the iPod’s impact on business, entertainment, and culture in about 250 pages. Levy weaves his narrative with lots of quotes and references to academic work on the subject. The book is never dry, however; Levy’s writing style is engaging and humorous (he refers to the record companies’ instruction to listeners to not download music illegally as akin to an etiquette lesson from the Green River Killer). He reports, interviews, and provides commentary in his examination of the ideas and issues surrounding widespread use of the iPod, although it is clear his book is only a measure of the iPod’s influence to date.

As popular culture continues to be distributed in an a la carte model (as witnessed by iTunes’ current offering of television series and episodes, film rentals and purchases, and audiobooks), and since acknowledgement of the iPod’s influence cannot be denied, it is anybody’s guess how future generations will view the iPod.

His rancid odor, of midnight smoke soaked in days-old liquor, broods around me. Somehow, intense smells at either end of the spectrum incite the same reaction. Heavy cologne. Sewer water. It’s the same. The man dangles a bottle in his trembling, muddy hands, and tumbles toward me. And his beard — his beard is the bearer of many wandering nights, like this one. I prepare to sidestep him as he approaches me, but the zigzagging couples shish-shinging their feet on an improvised dance floor detour his path.

“El tango te llama,” he growls as the swarm of tightly embracing dancers swallows him. The tango calls you. This tango, in Plaza Dorrego in San Telmo, Buenos Aires, nestled under the sweet daze of dim lights, is carried on the bandoneón’s (a free-reed instrument) cry through the whistling tree leaves, transpiring in the streets where Argentina recovers seven years after its gravest economic crisis.

Maybe it’s the fetor. Maybe it’s a drunkard’s aphorism. Maybe it’s the distorted lament pouring out of an old record player or the newness of my milonga (tango gathering) journey’s first stop, but here under the muted Buenos Aires sky, I feel close to the heart of tango, which perhaps beats more intensely after a testing ordeal. This tango is mortal, with flesh and sweat and stench, too human for the imagination — at least for my glamorous fantasy.

“Tango is a one-way journey,” Romina Lenci cautioned me before my trip. “You don’t come back.” Romina has surrendered to that fate; she has danced tango for more than a decade, and she sees no return. But that just emboldened me. I guess I’m just as intoxicated with the possibilities of tango — with the romanticism of surrendering to a stranger, with the relief of not knowing where I’m going and not caring — as any other rookie. But I have another morbid yearning: I want to confirm the doomed Argentine cycle, epitomized in the back-and-forth, twisting steps of tango. Tango, after all, is the well where Argentine thinkers and corner drunkards look for la argentinidad, the country’s identity. I wonder how, through all the nation’s upheavals, Argentina’s signature music and dance resonate in its people.

I throw a furtive look at Guillermo Segura, who, in utter contrast with the drunkard, stands stoically beside me, his tall, clean-cut silhouette squeezing through the mountains of shadows that stand shoulder to shoulder on the dusty wooden dance floor. Languid feet fly like birds over the peaks and valleys. Guillermo, eyes half-closed, remains silent, but occasionally blurts out little snippets about tango, about his life.

He started dancing tango after he separated from his partner.

He despises the old-fashioned tango rituals.

He’s just waiting for Argentina’s next crisis — economic or political.

A crisis every 10 years

Tonight, nothing seems to surprise Guillermo. Not this decaying lushness, not all the hype about his country’s miraculous recovery. In early 2002, the value of the peso dropped 75 percent. Five presidents took office in 10 days. Half the country fell below the poverty line. Five years later — an outstanding amount of time to come out of the mess that was Argentina — the new president, Cristina Fernández de Kirchner, seems to continue Argentina’s new chapter, which was started with her husband, Néstor Kirchner. But even this new chapter is tainted by doubt (reports about misleading inflation numbers emerge) and pessimism (economic gains still haven’t solved pivotal social issues).

And to that, Guillermo seems to stand unfazed; he submerges himself in tango and waits for the next low. “Every 10 years there’s a crisis,” he says. It’s a learned line that almost every Argentine disguises as a self-sabotaging joke. “It’s mathematical,” he grins as he counts in his head — just a couple more years. I wonder if he could smell the storm coming: In March, Argentina’s farmers went on strike — four months into the new president’s term — leaving Argentina’s stores and pantries empty.

To survive their tribulation, many Argentines are pinning their hopes on tourism to bring the country’s economy back to health. Tourism, an industry that boomed after the recession, is Argentina’s third source of revenue, bringing in more than $4 billion dollars in 2007. And in times of crisis, improvisation — as always — came in handy; the tango scene was reinvigorated with an increasing number of lessons and clubs. From three-figure tango packages at the Buenos Aires Hilton, to shows in La Ventana and Madero Tango, to low-key, low-budget classes in hostels such as Sandanzas, tango is the well Argentina is drawing from for its selling essence as well.

Its people, however, can’t help but cloud those hopeful signs with skepticism.

Here, in the half-lit Plaza Dorrego, in a culture of muffled extremes and controlled debauchery, nothing appears to have changed, yet everything has happened. Signs of the nation’s revival are clear though fragile, as they lie alongside the scars: graffiti decrying corruption and calling for presidents to step down scratch historic buildings; a beautiful boy huddling in a corner, eyes shut, lost.

Avenida Corrientes: a twilight zone

Having seen enough, Guillermo tries to figure out our way out of the labyrinthine cobblestone streets of the tango barrio (neighborhood).

“San Telmo disconcerts me,” he mutters as we dodge the cracks on the impossibly narrow sidewalks. We move swiftly, breathe in the spring’s silvery air, leave block after block behind us, cross over spilled garbage, pass the tumultuous Plaza de Mayo, where pigeons flock during the afternoon. Their flight, a mirage of lazy days, deflates the brewing intensity of innumerable protests. Then, the ever-expanding Avenida Corrientes, that decadent boulevard that harbors the porteño* sensibility and broods tango, unfolds before us.

It is around 10 o’clock; the streets are waking up for the famous Buenos Aires nightlife. There is no better stage than Corrientes to showcase its contradictions: the glitzy theater plays and hectic nocturnal revelry amid the constant rummaging of cartoneros (collectors of cartons) among the garbage. How true that old tango song, “Tristezas de la calle Corrientes,” sounds now:

¡Qué triste palidez tienen tus luces!

¡Tus letreros sueñan cruces!

¡Tus afiches carcajadas de cartón!

What sad paleness your lights bear!

Your billboards dream of crosses!

Your posters are cardboard laughter!

It’s like a twilight zone, la argetinidad and the blinding lights in an unusually deserted Corrientes. The street widens, and on its concrete horizon rests the translucent Obelisco, defiantly piercing the blue night. Guillermo is warming up to me now and is more talkative. So I ask this question, which I figure these days is as normal as asking how someone is: “How did you survive the crisis?

With a nonchalant tone, he said he was OK.

A physicist at an oil company. OK.

Did he want to leave, like the 300,000 who fled the recession?

“I like having a place to belong to.”

Buenos Aires is his home. And that’s that.

Tango: resignation and rebellion

We leave Corrientes and descend into the dim grotto of the subte, the metro. Our next milonga is several stations away. Encased in this metallic worm, blank stares and lifeless expressions seem to fade in the fluorescent daze as time creeps by with each lulling revolution. A slender Asian girl sits across from us, her black-tight legs crossed, her hair entangled in a bun, and in her lap, a tango-shoes bag. I can’t wait to get out.

As the train makes a stumping stop, Guillermo points out that just a few blocks away are the villas miseria (slums), which ironically are what the most luxurious buildings look out over. After the crisis, many moved into shantytowns and have not come out.

He falls silent, again.

I wonder if Guillermo’s deadpan expression and sporadic blasts of laughter are a disguise for that ingrained melancholy so well known in tango, an amalgam of resignation and rebellion to a condemned cycle: 1966 — rise of military dictatorship; 1976 — dirty war; 1989 — economy melts down; 2002 — half the population falls below the poverty line after years of illusory bonanza.

“Every 10 years there’s a crisis,” I remind myself; I’ve heard it so many times.

That roller coaster of a history resembles the ocho (figure eight) that milongueros (tango dancers) draw on the dance floor. With each dip it confirms what writer Ezequiel Martínez Estrada once said: “[Tango is] the dance of pessimism … the dance of the monotonous great valleys, of an overwhelmed race who, enslaved, walk these valleys endlessly, aimlessly, in the eternity of its present that repeats itself. The melancholy comes from that repetition.”

La Glorieta: scene of contradictions

Ten blocks and a subte ride later, we arrive at La Glorieta, a pavilion in Barrancas de Belgrano, one of the well-off parts of town. La Glorieta is a milonga hot spot during summer and spring. On this late October night, it’s packed. A nerdy-looking guy twirls his partner, the girl from the metro, counterclockwise. She does the caminado (walking) with her eyes closed and the side of her head glued to her partner’s.

I look around. It’s fair ground: all ages, nationalities, and skill levels. Amateurs, who stay in the middle, to veteran tangueros, who loop the outskirts of the round pavilion — and all with baggage, with something they need to forget.

“The milonga is a place that gathers very special people, lonely people, whose heads are a quilombo [mess],” says Romina, whose ancestors have danced tango for as far as she can remember. “Some people go to therapy, others go to milongas.”

In the months after the latest crisis, Romina noticed differences in the milonga scene: some perfunctory, some profound. To dance, people didn’t fix up as nicely as before. But they would go to the milonga after a cacerolazo, where, banging pots and pans, they would protest against the government.

La Glorieta is getting crowded. I huddle in a corner, still insecure of my tango skills and still rusty with the do-you-want-to-dance rituals. Guillermo has already done a few rounds. From one end, he spots me, and with an energy I haven’t seen before, he walks toward me grinning and introduces me to Regina Alleman. Poised as a delicate tulip, Regina talks with that Argentine cadence and glides her slim frame in the arms of a milonguero. I think Regina is porteña* until she says she moved here from Switzerland two years ago, following the call of tango.

It was the paradigm that attracted her. “The city, like tango, has this contradiction: joy and sadness, people that are open and people who are mistrustful [living in the same place and time].” Though she arrived three years after the economic meltdown, Regina can still perceive the fear in people. “However, [the crisis] did yield something positive: People live in the moment.”

In this moment, beads of sweat glide down foreheads, heels and sneakers mingle in a poetry of movement. It’s been almost an hour since I arrived at La Glorieta, and the crowd is overflowing. The music — a mix of old and new tango — fills the plaza: Los Reyes del Tango, Juan D’Arienzo, Orquesta Fernández Fierro, Osvaldo Pugliese, and an occasional batch of salsa, rock, or swing between rounds of tango.

My eyes sweep through the swarm of milongueros, and suddenly they meet with the stare of a woman leaning on the fence. Señora Ramona, a 50-something porteña who lives nearby, frequents La Glorieta, but not as often as before, she tells me. She fears for her safety; the streets of Buenos Aires have roughened up. I ask for her last name. She declines. And then she hugs me, tells me to take care, and walks away. I grin as I begin to savor the charm of tango’s contradiction.

“Yo soy el tango de ayer…” I’m the tango of yesteryear, an old man sings.

The last note dies away, but lingers in memory. The crowd spreads to all directions, and I reunite with Guillermo at the foot of the stairs where a line of girls are taking off their heels and changing into tennis shoes. Sandra, a petit brunette with a quick smile, packs up her tango shoes and pulls out a map from her bag. We join her and agree to go to Porteño y Bailarín, in Riobamba.

The night is young.

A sad thought danced

On the meandering route 29 bus, our newly formed trio navigates the clogged veins of a proud, bruised Buenos Aires, the city of Jorge Luis Borges, of “the uncertain yesterday and different today,” the home of 11 million souls. A bump, a turn, a stop. I begin to feel Buenos Aires’ beat. Through the fingerprint-stained window, I see patches of light and darkness; European-style buildings and unassuming houses; shadows swallowed by the light of a night lived as day.

Porteño y Bailarín bears a more formal demeanor than La Glorieta. Guillermo is not fond of this smoky place: He doesn’t like the old rituals, like the cabeceo (when a man asks a woman to dance with a head movement), that are still practiced in traditional milongas, and the two dance floors — one for veterans (all dressed in dark attires, sitting stoically at minimalist tables) and another for the younger, rookie crowd, squeezed in the back.

Sweet cologne, aired wine, used air. We make our way through the hall. I’m smelling smelled odors; I’m seeing seen scenes. A few heads turn, murmurs tickle our ears as we scurry among tables. I’m walking walked paths, of immigrants, of prostitutes, of taxi drivers, of pathologists, of seized memories. In the back, we find a spot. Is this la argentinidad? Squeezed between social lines, among the cracks of a tired valley, walked over time and again? Reinventing, reducing, resuming the journey to a known end?

Extremes, in the end, meet at the same place.

“Do you tango?” a man asks me from his corner, skipping the cabeceo ritual, breaking conventions.

“No,” I say from my end. I’m tired. I’m afraid. I’m not ready to plunge into the endless walk of tango. Not tonight.

But Guillermo, despite his reservations about the place, lunges into a tango with Sandra. It’s better to dance than to stand still.

“Tango is a sad thought you dance,” Enrique Santos Discépolo once said. The venerated tango lyricist’s simple definition is in each step Guillermo propels and Sandra anchors — two shadows merged in their solitude, furling, breaking the monotony of the green walls that shelter their ephemeral escape from reality.

I silently count the number of years to the next crisis. Five or four. That omen invariably hangs over every Argentine’s head. But this night is old and tango is alive in Buenos Aires.

Guillermo walks me to a corner and helps me grab a cab back to my hostel. We promise to see each other the next day; we’d never fulfill it. I hop in the taxi. The city shines through the cab’s window. The humid streets emanate a heavy, fishy mist, and once in a while I’d see dead pigeons on the sidewalks.

* Porteño/portena refer to an inhabitant native to Buenos Aires.

Kyla Pasha and Sarah Suhail have stirred up the blogosphere with the launch of Chay magazine — a publication about sex in Pakistani society, from a feminist and gender-inclusive perspective. “We at Chay magazine endeavor to bring to the Pakistani reading public a place to converse about those things we are most shy of,” reads the magazine’s mission statement. ITF chatted with Pasha about taboos, international feminism, and the reclaiming of pejorative words (“chay” is a polite euphemism for “chootia,” an equivalent to “cunt”).

Interviewer: Sarah Seltzer

Interviewee: Kyla Pasha

Tell me a little bit about the personal journey or set of beliefs that led you to found Chay. Has this been something you’ve wanted to do for a while?

Not as such. I’ve always wanted to have a magazine or a writing concern of some kind. I met Sarah Suhail about a year ago, and in the time that we’ve known each other, a lot of things have happened in Pakistan: there’s conflict around the sacking of the judiciary last year by the president; there have been media freedom issues and protests; the marriage between a transgender man and a woman was dissolved and reviled in the press.

Sarah introduced me to the protest circuit, and I found myself getting a little more politically active than I’d originally planned. A couple of months ago, we were having a conversation about what we thought was missing from public discourse. We came up with Chay.

How do you envision a magazine like this can change the public discourse in Pakistani communities? Does it come down to the fact that for women worldwide, the “personal is political”?

“Personal is political” informs a great deal of our approach here. We’re both products of feminist education in one way or another. But more than that, we realized when the Shamail and Shahzina case happened [the transgender man and his wife who were imprisoned] that Pakistani don’t have a way in which to talk about sex that is not derogatory, abusive, or silencing. Far from sex ed [sex education] in school or even the home, straight, young people aren’t even comfortable talking about being in relationships.

The perils of that kind of silence are great. We’re hoping that Chay will provide a platform on which people can talk about their experiences and concerns, and listen in to what others are saying.

Do you worry about being pigeonholed as either a fluffy women’s magazine or alternately, a radical feminist magazine?

We anticipate being pigeonholed as something sinful.

But you feel the power of your collective voices can help break down some of these notions of sin and taboo?

Can help, yes. “Help break down” is sort of the key here. It’s an uphill battle at best, and we’re aware of the unpopularity of the idea — we have been made aware by folks writing in and by conversations on other sites discussing Chay. Mostly, we’d just like to have the conversation.

Can you elaborate on some of the positive and negative responses you’ve been getting so far?

We’ve received a lot of encouraging responses from people who are interested in writing for us. They call it “a breath of fresh air” and just what was needed, which is very gratifying. We’re particularly hearing from queer women and some queer men on how much they’re looking forward to the forum.

We’ve had negative responses on the title of the magazine. The letter “chay” in Urdu stands for a curse word, chootia, which means something close to “dumb ass,” but by calling it “cunty.” “Chay” is used as a euphemism among polite folk who don’t want to say the whole word, but mean it. We’re reclaiming “chay” to mean all the things that we’re supposedly not allowed to say. The negative feedback in one particular case was that we’re not reclaiming it successfully and are being derogatory toward women.

In your mission statement, you note that while the magazine is primarily aimed at the Pakistani community, the online aspect will help bring you into the global feminist conversation as well.

That’s the idea. We’ve been researching major feminist blogs as well as sexual and queer rights issues in our neighboring countries. India is particularly interesting in that regard, and we’ve had some contributions from there already.

As you research global feminism, does it frustrate you to continually see ignorant western journalists throw up their hands and moan about “where are the Muslim feminists?”

Firstly, if I got frustrated by ignorance in the media, of anywhere, I’d have died of [an] aneurism by now. Secondly, for me, the conversation is not really with people who can’t see past the end of their noses.

There are lot of people who say “Where are the Muslim feminists?” who haven’t looked very hard. And there are a lot of people for whom feminism does not include veiling yourself voluntarily or taking your clothes off for Playboy if you want to, or exercising your choice and agency in other ways. If I start a conversation, invite everybody, and 10 people don’t come because they think I’m not feminist enough, or Muslim enough, or straight enough, or gay enough, then they missed out.

For us, this is about conversations in Pakistan. Other people can talk about us as objects if they want, but it’s of limited relevance. I’d rather they talked to us. But, you know …

What about western feminists, who can also be ignorant about global feminism? Do you hope that Chay can be part of a new movement to make the face of feminism more inclusive and worldwide?

The idea of inclusivity to me is a bit false. It suggests that I, as a Pakistani Muslim Feminist — which is not an identity I carry around all time, but just for the example — would like a seat at some bigger United Nations of Feminism table.

There’s a table right here. There’s a lot of us already sitting at it. Moreover, there are a bunch of other tables. And people wander from conversation to conversation. That’s my ideal. There is, out there, a certain capital “F” feminism that has achieved that status because it’s white-skinned and “mainstream” US. But it has that status from a particular privilege. It does not reflect everyone’s reality.

Are you planning to be an online-only magazine, or are you going to have print issues as well?

For now, we’re online-only. We’ll see if there’s a market for print in due course and maybe go into print as well.

You have a poetic and artistic background as well as a literary journalistic one, right? You’re going to be publishing creative work as well as journalism?

Yeah, I’m a poet myself. And we’re open to fiction, nonfiction, poetry — all kinds of work. Creative expression is cathartic and part of political work, so we didn’t want to just do journalism and commentary.

Can you elaborate on how you think creative expression can help achieve political ends? Are there any examples of creative work that have inspired you politically, or political moments that have inspired you as a poet?

Visual art in the Pakistan in and since the ’80s has been extremely political and feminist. It responded to the brutal dictatorship of Zia-ul-Haq, who promulgated many misogynist and bigoted laws in the name of Islam. Many artists, mostly women, responded in their work, and it has served as one of the major avenues of empowerment and feminist expression in Pakistan.

So you’re working within an established tradition?

Absolutely. That tradition has not touched on sexuality in quite the way we would like, but we are in no way reinventing the wheel here. We’re taking our cue from our parents’ generation.

Are there any articles in the first issue that you’re particularly excited about?

There’s an article about homoeroticism and masculinity in the public spaces of Lahore that I’m excited about. There’s some great poetry and artwork. And there’s an article in the pipeline about sex work and HIV [the AIDS virus]. It’s going to be fantastic. I’m totally psyched.

Do you think it’s difficult for people to see a magazine about sex as informative rather than titillating?

I think it might be. It’s definitely a danger. But I’m confident that we’ll clear the bar with room to spare. Again, if someone looks at it, sees that we’re talking about sexual rights and marginalization, education, and the law, and still feels we’re here to titillate, then we’re not sitting at the same table. That’s fine, so long as no one throws stuff at us over it.

You may or may not think that the stimulus checks the government is sending out this month make good economic sense, but either way, you’ve got to decide what to do with the extra 300 to 600 bucks. You could buy yourself a bottle of 1980 Dom Perignon, for instance, or take yourself and 29 friends to see Speed Racer. But in case you want to put some of your windfall to work for a good cause, here are 10 specific, action-ready ideas:

You may or may not think that the stimulus checks the government is sending out this month make good economic sense, but either way, you’ve got to decide what to do with the extra 300 to 600 bucks. You could buy yourself a bottle of 1980 Dom Perignon, for instance, or take yourself and 29 friends to see Speed Racer. But in case you want to put some of your windfall to work for a good cause, here are 10 specific, action-ready ideas: 1. Feed the grassroots.

Send your money directly to the people who need it by using the online system at GlobalGiving.com, which pairs "average Joe" donors with grassroots charity projects around the world. It’s eBay meets foreign aid, with projects searchable by topic, country, and a host of other criteria. GlobalGiving has just launched a resource page and a relief fund to help victims of the Myanmar/Burma cyclone, which has left up to 1.9 million people homeless, injured, or vulnerable to disease and hunger. www.globalgiving.com

2. Offset yourself.

Worried about climate change? Whether you’re reducing your own carbon footprint, you can use the cash to buy carbon offsets, which fund projects designed to counteract atmospheric pollution and global warming. Carbon Catalog provides a long list of providers and information about transparency and verification. www.carboncatalog.org

3. Help the troops phone home.

Think "support the troops" has become a platitude? Do something real to help servicemembers serving abroad by paying for their calling cards so they can keep in touch with their families back home. If you don’t have a person in mind, look at the bottom of this page for ideas: thor.aafes.com/scs

4. Fight poverty.

While the government has decided to give most people a tax rebate, families of few means will receive smaller checks, and sometimes nothing at all. You can make sure resources go to the people who need it most by making a donation to the Low Income Investment Fund, which helps low-income communities develop in a sensible way and avoid the poverty trap. www.liifund.org

5. Fight racism.

Want to do something concrete about racial injustice in the United States? The Applied Research Center advances racial equality through research, advocacy, and journalism. Their work helps to change both policies and minds. www.arc.org

6. Fight homophobia.

If you think that human rights should include the right to love, consider donating to the Astraea Lesbian Foundation for Justice. Astraea supports social justice in the United States, and organizations that benefit LGBTI communities worldwide. www.astraea.org

7. Don’t donate it … loan it.

Microcredit is a burgeoning field that fights poverty by making small, targeted loans in order to foster entrepreneurship in developing countries. Two organizations (one for-profit and one non) offer you the chance to personally finance some of those loans. Your investment may even make a little money at the same time. www.kiva.org / www.microplace.org

8. Do more than talk about Tibet.

Speaking out against China’s record on human rights is a good start. But why not put your stimulus check where your mouth is? A donation to The Tibet Fund will deliver needed resources to the educational, cultural, health, and socio-economic institutions inside Tibet and the refugee settlements in India, Nepal, and Bhutan. www.tibetfund.org

9. Nurture young minds.

Support the arts as a way to empower young people by giving your tax rebate to Girls Write Now, a creative writing and mentoring organization for high school girls in New York. www.girlswritenow.org

10. Support independent media.

We’re not too proud to suggest it: Donate to your friendly neighborhood nonprofit online magazine! www.inthefray.org

Update: Another worthwhile use of your tax rebates would be donating them to help victims of the recent earthquake in China, which has left tens of thousands of people dead or missing. Consider donating to the International Response Fund of the American Red Cross (www.redcross.org), Mercy Corps (www.mercycorps.org), or World Vision (www.worldvision.org).

While nature versus nurture may be one of those perennial questions, for people like Pippa Dunn, the protagonist of Alison Larkin’s new novel The English American, it’s not just academic. Pippa is the eldest daughter in a stiff-upper-lipped British family; she knows how to make a proper cup of tea, likes Marmite, and so on. However, where the rest of the Dunn family is neat and orderly, quiet, and focused, Pippa is outgoing, messy, artistic, and spontaneous. She’s always losing her things, forgetting to scrape the bowl clean before putting it in the sink, and she secretly hates Scottish dancing. She’s not happy at just any old job — she wants to follow her bliss and write plays. Pippa’s sure that her personality traits reflect those of her birth parents; she’s known that she was adopted since she was a small child. Now, as an adult, Pippa learns her parents are American — Southerners to be exact.

Feeling rudderless and out of place in England, Pippa tentatively reaches out to her birth mother in the United States, hopeful that she will measure up to the ideal that Pippa’s carried with her all these years: “She was beautiful, and delicate, with red hair, like mine, only hers wasn’t springy … The sight of her filled me with warmth and made all the fear go away.”

Her reunion with Billie, a flighty and exuberant redhead, is at first validation for Pippa — here is the woman from whom she inherited her enthusiasm for life, her creativity, and her relaxed attitude toward tidiness. Pippa also reconnects with her father Walt, a Washington, D.C.–area businessman who is actively involved in international affairs.

Joy and relief at finding her appearance and personality reflected in the people who gave her life soon turn to the cold realization that while Billie and Walt may be her parents, they don’t behave like family. Billie’s manipulative attempts to make Pippa reciprocate her neediness in the relationship and Walt’s hesitance to divulge Pippa’s existence to his wife and children leave Pippa feeling as out of place as she did before.

The English American is threaded with a romantic subplot that expertly and subtly evokes Pippa’s assumptions about other people’s identity as she struggles with her own. It provides a nice twist to the main storyline, save for when it involves Nick, a tortured artist type whom Pippa thinks she loves from afar, and who appears in the book almost exclusively via email messages. Where the relationship between Pippa and Nick is concerned, the storyline goes off the rails a bit, since so little about Nick is revealed until the final chapters, and the only communication between him and Pippa is through email; he’s a comparatively flat character.

Alison Larkin’s take on the issue of identity, while couched in a fast-paced contemporary novel, infuses the subject with realism, humor, and compassion. Larkin’s writing is at her finest when she is plumbing the depths of Pippa’s psyche. The novel echoes elements of her one-woman show, The English American. Larkin’s own life aligns with Pippa’s somewhat, as Larkin too is an American-born adoptee raised by a British family.

From the red tape and bureaucratic delays Pippa encounters in trying to obtain the names and contact information of her birth parents, to introducing herself (albeit with a posh British accent) in a bar as a “redneck,” Larkin’s ability to know just when to use a light touch buoys the darker, more emotionally powerful scenes in which Pippa’s self-reflection takes her to the depths of acknowledging who she is, who she wants to be, and how much she may or may not owe her parents.

Pippa comes to realize it is up to her alone to reconcile her roots and her upbringing. Until she can navigate the rocky boundary between genetic and environmental influences, she can never feel comfortable in her own skin. And while people may continue to argue about the influence of nature versus nurture for as long as they’re able, at least Pippa Dunn finds peace as she settles the question for herself.

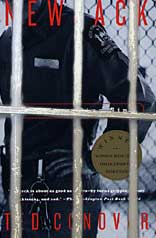

Ted Conover's book about Sing Sing got him a Pulitzer nomination. It also brought him nightmares.

Ted Conover's book about Sing Sing got him a Pulitzer nomination. It also brought him nightmares.

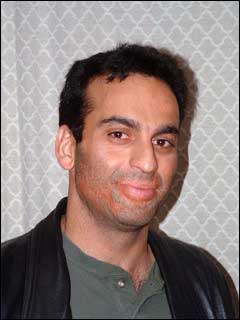

Ted Conover just feels familiar, as if you have been introduced somewhere before. He has a simple face with tired, intelligent eyes and a soft voice. Any number of humble identities could suit him: a small-town lawyer in a smart pair of suspenders; a Northern California dude growing a couple of acres of pot; a brainy priest who nonetheless likes his scotch. Your last guess would be a tough-guy prison corrections officer, which, in fact, he was, roughly 10 years ago.

Conover was a guard at Sing Sing Correctional Facility, New York state’s toughest prison, for just shy of a year, but the job marked him. Like a soldier returning from war, nearly a decade later he says the unusually brutal prison visits him when he sleeps. Yet, unlike tight-lipped vets who often refuse to talk, Conover has, for the past two years, taught a class of New York University journalism students from his troubling book about Sing Sing, Newjack. He not only discusses the violence that he witnessed, but the violence he condoned as a rookie guard. The graduate seminar is called “The Journalism of Empathy,” and it seems a class long overdue.

During spring 2007, the seminar met on Mondays in the Carter Building, a block from Washington Square Park. If the building was a bit rundown — worn carpets, creaky elevator, and gloomy stairwell — the journalism students inside it were generally not. The half dozen lingering outside the classroom and those walking up and down the halls had surprisingly fresh faces. They all seemed a little young, a little undergraduate.

Conover arrived at the classroom carrying a brown shoulder bag, dressed in a black jacket with a black knit cap, looking like a merchant marine arriving from the docks. Sophisticated, even savvy, he didn’t seem to have one ounce of guile. But this gentle bearing was misleading.

In the 1990s, Conover asked New York corrections officials if he could write a story about a trainee going through boot camp. When they refused, he quietly applied for the job. On his resume, he noted a bit of journalism experience, but left off his ties to The New Yorker and the two books he authored. He turned in the application and forgot about it. Two years later, a letter arrived ordering him to report for training in three days, and while Conover knew being a corrections officer (CO) would be tough, how bad it actually became was shocking.

At New York University, Conover sat with his students at a long, brown table, with a cup of coffee and a pen. Behind him were a large whiteboard and a jumble of audio visual equipment. He had an unshakable cold. He said quietly, “I apologize. I hope I don’t lose my voice.”

Using first person, or “I,” in narrative nonfiction to empathize with the subject can be quite tricky, said Conover. A writer has to get uncomfortably close to the person, the subject. And the subject can often feel misled or betrayed, or can suck the journalist into his world, blurring the lines to an impossible degree, sometimes destroying the writer’s integrity. So Conover, who has an anthropology degree, relies on an ethnographic technique called “participant observer” to help his students negotiate the line between “I” the journalist and the subject.

Curious about their work’s legal and moral complications, a young woman at the end of the table was worried. What if she witnessed something clearly illegal? As a journalist, do you get involved?

“I mean, what do you do? Would you be considered an accomplice?” she asked. “I mean you’re not including it in your work, but if you’re aware of it and you’re taken in for questioning, you can get in a lot of trouble.”

Conover started nodding even before she finished her question. Does a journalist stop being an outside observer when witnessing, say, child abuse?

“So I guess I’m just wondering,” the girl went on. “My question is: Where is the line?”

“Yeah,” said Conover, his voice becoming more raspy.

“… Is there a line? Do you flirt with the line? …”

“There’s gotta be a line,” he said, still nodding. “You have to have a line.”

Bizarro World Romper Room — with guns and iron bars

Conover’s own line blurred to an impossible degree while at Sing Sing, but a year after leaving the prison, it finally disintegrated. Just months before Newjack was published, in September 1999, he had begun recovering his life with his wife and child. He was lying in bed at home with the television on, his eyes closed. Exhausted. That’s when he was confronted with the past that he was trying to leave behind.

Sing Sing had done a tap dance on Conover’s psyche. In those winter mornings before going on duty as a guard, he sat in his car steeling himself before walking through the frozen gates. Guessing when the day-to-day violence particular to prison might boil over was unnerving and agonizing. He hated the job.

One guard Conover wrote of in Newjack, a real bastard by most standards, had once been taken hostage and tortured by inmates who seized the prison many years earlier. Conover later discovered that the guard’s rigorous, insulting, and unbending professional ethic partly arose from the fear of that happening again. Prison was basically “Bizarro World Romper Room” with guns and iron bars. Relationships with prisoners were stark and authoritarian, and the inmates challenged the guard’s authority daily in a thousand maddening ways.

Sometimes, they were relentlessly childlike: begging to take a shower, refusing to lock up, hanging sheets on the bars, breaking the little rules — “Oh please, come on CO! Come on, pleeeeeaaasse!” Or the inmates would give him a long stare that promised murder. Sometimes the bitterness would cross over into random assaults. Conover was sucker-punched in the head once when he walked past the cell of an infuriated inmate. Women COs had sperm flung on them. One inmate squirted piss from his mouth onto passersby.

Civility inside Sing Sing was not an option. And Conover, a thoughtful man searching to illuminate life’s daily contradictions, could not afford to be scared. To a prescribed degree, COs were allowed take down violent inmates, and Conover found that sometimes he longed to inflict undue pain.

“Guards don’t dare admit that all of us at times feel like strangling an inmate,” Conover wrote in Newjack. “That inmates taunt us, strike us, humiliate us in ways civilians could never imagine, and that through it all the guard is supposed to take it.”

Conover had not anticipated Sing Sing’s brutality. But he embraced it, slowly, immersing himself in the prison system’s logic both as a guard and as a journalist. Conover’s immersion journalism came from his study of anthropology at Amherst College (Massachusetts) in 1980. There he mastered the techniques of the participant observer, which ethnographers rely on to study their subjects, often living with them for extended periods of time. But while engaging a native is fine, going native is a bad idea. Using a set of research strategies — informal interviews, long-term immersion, self-analysis — the participant observer method helps keep the anthropologist oriented and aware of his ever-evolving relationship with his subjects.

One day, a well-read prisoner named Larson passed Conover an outdated book about anthropology through the bars. The book hailed from the days when the science tried to break down people into racial categories.

“Ah yes,” I said. “They used to worry about this stuff a lot.”

“Who?”

“Anthropologists.”

Larson stared at me. “What’s your story Conover?” he asked a moment later. “You’re not like the other COs here.”

“What do you mean? You mean because I’m not from upstate?”

“No, it’s something else. The way you think and the way you walk.”

During his nine months at Sing Sing, Conover told a few friends what he was up to; otherwise, he kept his mouth shut and stuck it out until New Year’s, when he felt he had a natural ending to tie up the book. He held on for the spectacle of inmates celebrating the holiday with controlled fires set ablaze throughout the prison. And he also held on to satisfy his pride. Then, to the relief of his wife, he finally left.

But Sing Sing had seeped into his private life — a civilized world where education and kindness were not considered weaknesses. His marriage had become strained. He was physically exhausted and mentally divided in half. Every night, when he returned home from the prison, he retreated to his office through the back door, without telling the babysitter or his wife. He would type up his day, he understood later, to escape the brutality and peaceably reconcile his double life as best he could.

Though Conover quit Sing Sing, there was one prisoner he couldn’t leave behind: Habib Wahir Abdal, who was serving 20 years for rape, his second prison term. Abdal was one of those poor clichés, the prisoner who swore he was innocent. Whenever the two chatted, Abdal insisted he hadn’t done it. After a few looping conversations, Conover became weary and disappointed at Abdal’s denial. There was no point in arguing, and so Conover just nodded and would say, “okay, okay.”

Then, almost a year distant from the nightmare, free from the daily lies and deception, while lying in bed in the flickering glow of late-night television, Conover stirred to watch the breaking news. He opened his eyes. And he suddenly discovered he was in fact on the far side of a line he hadn’t seen.

“They didn’t even get around to mentioning his name until the end,” says Conover. “I looked at the TV, and out of Green Haven comes Habib and his lawyer, Eleanor Jackson Piel, and Barry Scheck. And I thought ‘Hoooooly shit! He was telling the truth.’”

Mama Piel

As literature, Habib Wahir Abdal’s life story was knitted together as tightly as a Dickens novel. It even had a perfect, melancholic ending. Abdal died in his bed, a free man, in 2005.

His body was found, still warm, by his lawyer, Eleanor Jackson Piel, who had fought his legal battles on and off since 1969. Piel traveled to Lackaw, New York in 2005 to discuss Abdal’s ongoing civil suits, and found him lying in his bedroom. She laid her hand on his body. His eyes were closed. He used to call her “Mama Piel.”

“Yeah, it goes back a long time,” Piel says fondly, while sitting at her desk in her Upper East Side law office.

In a black suit with a silver butterfly brooch on her lapel, Piel’s dark hair was pulled taut into a bun, giving prominence to her handsomely creased, hawkish face. She recounts Abdal’s life as if it were a long-forgotten gem rediscovered in her jewelry box.

She first met Abdal years before he was falsely convicted of rape, before he converted to Islam in prison, back when he was named Vincent Jenkins, a young hustler arrested for homicide in New York City in 1969.

“Evidently he won a large bet, and other people knew he had money and were chasing him. And I think they found him in a house. They came after him. And one of them slit his arm. He ran away and he got a gun,” Piel says, describing the circumstances of Abdal’s manslaughter conviction after he killed a woman and shot a man. “And there were witnesses who saw these people chasing him. I contended he was not guilty because it was self-defense.”

Piel fought the conviction for years.

“I was very emotional. I was very upset,” says Piel, and then she smiles as if a little embarrassed. “Oh, I was younger then.”

After serving his manslaughter sentence, Abdal moved to Buffalo, New York in 1982, where police snatched him off the street and falsely charged him with rape. They manipulated the victim to choose Abdal from a line-up, Piel says angrily, and convicted him in 1983.

Plot twist: Piel’s husband, Gerald Piel, was the publisher of Scientific American. After reading a few articles on DNA testing, Ms. Piel decided to have samples from the rape kit tested. But DNA testing in the late ’80s was “shaky,” Piel explained, and if Judge Elfklin, a federal judge in the Northern District — notorious for slow rulings — hadn’t sat on the case for years, premature testing might have failed to free Abdal.

A first round of tests in 1993 was inconclusive. But five years later, Piel, ready to try again, asked Barry Scheck of the Innocence Project, who specializes in DNA exonerations, what he thought of the Boston lab she had used previously and whether she should do so again.

“Barry Scheck said, ‘Oh that’s a terrible laboratory! Don’t send it to that laboratory!’” says Piel, laughing. “He said there’s only one man who can do this, and that’s Ed Blake, and he’s out in Northern California!”

Within a year, Abdal was free. Under the fair compensation laws in New York State, Abdal’s attorneys, Scheck and Piel, sued for $4 million dollars. When the state offered a $2 million settlement, Abdal said “no way.”

Abdal wanted his day in court and a jury to proclaim his innocence “and that was that!” Piel said while laughing, “We had no idea what to do! Then Barry Scheck had the idea to start a civil suit for the year Abdal was in jail before the trial, and so Abdal finally took the money.”

Six years after leaving Sing Sing, Abdal died of lung cancer, and his surviving family members contested his will. He had left his millions to his mosque and to a close friend, cutting his family out completely because he didn’t trust them.

“They thought there was some skullduggery going on,” says Conover, who found himself somewhat drawn into the legal battle. The siblings hoped that he would testify that Abdal couldn’t read, to prove that he could not possibly understand any legal papers he may have signed.

“And it was kind of an amazing question to me because I’d always assumed he could,” adds Conover, who had stayed in touch with Abdal over the years, but learned of Abdal’s death months after the fact.

“It was galling when I realized I wouldn’t make a reliable witness about that. I wasn’t sure,” says Conover. “He’d never sent me anything in writing.”

Even the most thorough of journalists can miss an obvious fact. This is true, in part, because presumption is instinctual, a necessary skill in a blindingly hectic world. Likewise, Conover failed to recognize Abdal’s innocence out of necessity: prisoners had to be guilty to justify Sing Sing’s degrading ruthlessness.

Abdal’s role in Conover’s work couldn’t be second-guessed. It was a bruising epiphany for the author to realize his complicity, and so later, when asked to testify against Abdal’s wishes, Conover respectfully declined.

Yet, to this very day, nearly 40 years after they met, Mama Piel is still fighting Abdal’s legal squabbles.

The unseemly production

It was early spring — March — a month after his class discussing the line between reporter and subject. Conover sat looking at his hands as he lectured from Newjack, struggling to be precise as he spoke softly. He seemed to avoid telling the horrific story completely by rote. He said that he often felt guilty for bringing Sing Sing into his wife and child’s lives, but he never mentioned the anguish he felt over helping to imprison Abdal.

A young woman raised her hand. How had the compassionate intellectual sitting at the end of the table become the taciturn disciplinarian of the book? Were there two Ted Conovers? Was the hardnosed, matter-of-fact narrator a literary device? Conover, a bit rattled, explained that even today some part of him was still a CO.

The class was skeptical.

Conover stood up and stepped into character. He became a guard again, returning to a time when Sing Sing COs were outnumbered by the prison’s inmate population and Abdal was still guilty. When Conover had discovered he was as much prey as predator.

A guard needed to control the prisoner and himself — no doubts. This illusion of control was a brutal paradigm his psyche had suddenly recovered, as if he had gone back to the crux of that founding contract between man and state. Egged on by the class, he demonstrated his frisking skills, recalling the days he sometimes found himself at odds with Sing Sing’s violence, reluctant to dehumanize a man. He picked out his tallest student, Michael Tedder, directing him to assume the position. In Newjack, during a horrific frisk, Conover’s worries if a prisoner is ill:

He stood in front of me on a small square of carpet, briefs in his hands. He offered them to me, and I checked them quickly. There was some blood in the seat. “You okay?” I asked. He nodded, and I began directing him through the obligatory motions. But he knew them better than I did and was always a step ahead.

Jackie Barba, a cherub-faced, sharp-witted student sitting in Conover’s classroom, who had studied literature in college, wasn’t completely buying it. Her professor was obviously acting out a role, a humorous facsimile, she thought. “It made me wonder,” Barba said after the class. “You know, whether when he was in it, he was always acting and always a little amused to see himself in that role?” When Tedder looked around, Conover snapped “Face the wall!” The class giggled.

Later in Newjack, while being frisked by a guard, an inmate mutters, “You fucking OJTs are a pain in the ass.”

“What?” The officer asked.

The inmate took one hand off the wall and began to repeat the phrase, but was immediately jumped by the frisking officer and several others. When I heard about it, I was proud, because it showed we weren’t wimps.”

To endure Sing Sing, Conover reluctantly embraced its logic, both as a reporter and as a guard. Proud of the violence and embarrassed by his power, it split his psyche in two. But when forced to, he chose to exercise the brutal requirements Sing Sing demanded.

“I think taxpayers are quite happy not to know the details of all the dirty work that is done in our names,” says Conover over the phone in a soothing voice, “just as we’re happy not to know the details of how our hotdogs are made, or everything that’s going on in the kitchen. In fact, we pay not to know about that. So I’m always interested in the work that seeks to narrow that distance and implicate consumers in the unseemly production of something we need.”

Yet, even as Conover taught Newjack with his “prisoner” in a pat frisk stance, his thoughtful students — some amused, some unsettled (“It was kind of weird,” one said) — had trouble wrapping their heads around their professor’s post Sing Sing rationale. Though none ever doubted their professor’s sincerity, a few still had trouble accepting his willingness to embrace an authoritarian self.

Being one of the few male students in the class, Tedder later noted it was likely why he was picked for the frisk. That Conover got into fistfights or was beat up while working at Sing Sing surprised him. “How could this sweet man do this?” said Tedder, adding “but people really are multifaceted.”

After Tedder sat down, Conover drew a long black line on the white board. He wrote “participant” at one end and “observer” at the other end. His students took turns discussing where their semester’s work placed on the numbered line.

One woman had entered a beauty pageant, but few had come close to full “participant” to report their stories. Allie Zendrian, writing about a self-proclaimed ghost hunter, chose to observe her subject without involvement. Barba observed a class of budding comics take to the stage, terrified to try out stand-up comedy herself. Most students weren’t prepared to cross the line, but all of them now knew better where theirs was.

Conover says he would never do it again, immerse himself as deeply as he had to report Newjack. And frisking down his students, even in jest, suggests that his line is still blurred. An innocent man suffered, and Conover did nothing — could do nothing — because he couldn’t afford to doubt. In fact, it was shortly after Conover finished Newjack — after Abdal was freed and Conover realized his role in the injustice — that the nightmares began.

“There are people who think it’s immoral to be a prison officer. I’m not among them,” says Conover, “and I think it needs to be considered honorable work if it’s done in an honorable fashion. But I never anticipated that the work would involve something clearly as illegitimate as locking up an innocent person.”

Lackawanna

It is not as if Conover hadn’t tried reconciling his role in Abdal’s incarceration. He took time with Abdal when he visited New York City, and they roamed the city together: “I remember him looking around for the fragrant oils he liked to rub on his head,” says Conover. And when six American Yemeni men from Lackawanna were arrested for training with al Qaeda in Pakistan and Afghanistan, Conover, looking for a story, stayed as a guest at Abdal’s house in Lackawanna: “I ended up sleeping on his couch for a couple nights and spending whole days with him.”

He even wondered whether there was a book about Abdal’s life — it was never written. But Conover did appear with Abdal at the bookstore Talking Leaves in July 2001, shortly after Newjack came out in paperback.

“I went up to Buffalo and saw him the morning of my reading, and he asked if he could come. So he did. He ended up being a part of the whole presentation,” says Conover. “He brought his prayer rug and his tape player to my room at the Hyatt when I changed, so he could do his evening and afternoon prayers.”

Talking Leaves employees pushed back the bookshelves, sliding them away and putting chairs in where they could fit them. With 30 seats and standing room, perhaps 100 people attended the modest reading. At the front of the store, at a small table, sat Conover and Abdal, ready to take questions. Conover wore a blue shirt with his sleeves rolled up, and Abdal was in Muslim garb with his silver whiskers, polished bald head, and knotty walking stick, looking every bit the elder wise man. Conover gave his short reading and answered questions. Some he deferred to Abdal, who launched into respectful, if biting, monologues on the prison system, even as the corrections officers in the audience squirmed in their seats.

“It was a very interesting mix,” says Conover, “and my book, I think, attracts a readership that’s somewhat the same. It’s, on the one hand, people concerned about prisons as a social problem, themselves intrigued by prison reform and what my book might suggest for it. And then on the other side, there are people in corrections or law enforcement who know that this profession is sort of a degraded one, and a stigmatized one.”

Post-traumatic stress disorder

The afternoon was all that Conover had hoped for: that Newjack wouldn’t preach to any choir, but would rather “narrow the distance” between natural antagonists, forcing them all to face an uncomfortable truth of the prison’s complicated nature — at the blind spot of reason.

But his deep-immersion, first person reporting, his participant observer methodology, cost him as he sought that dangerous ground. In Newjack’s paperback afterward, Conover wrote that he had discussed his nightmares with psychologists at a medical convention. They supposed his nightmares were post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Conover respectfully shrugged and wrote:

That seems rather a grand name for it, and I don’t want to suggest that I went through anything like what soldiers who saw combat in Vietnam did. But I do think that if you repress something regularly (in my case, fear), it’s going to come back to haunt you.

The general thinking on PTSD is that writing down horrific events helps the traumatized to recover. In a way, the balm is almost too obvious. But only recently has this thinking been recognized in newsrooms like CNN International and the BBC. Frank Smyth, an investigative journalist captured during the first Gulf War in Iraq, suffers from PTSD. Smyth says that much more is needed to support journalists who suffer the disorder. Smyth also happens to be the Washington representative for the Committee to Protect Journalists, and writes for the Dart Center for Journalism & Trauma. He recommends that journalists, who often booze it up to self-medicate, instead confront their emotions by expressing themselves through art or memoir. It seems the brain can literally heal itself through self-expression.

“The act of articulation — writing, drawing, painting, talking, or crying,” writes Smyth with co-author Joe Height, “seems to change the way a traumatic memory is stored in the brain, as if it somehow moves the memory from one part of the hard drive to another.”

Conover, to a degree, instinctively embraced Smyth’s counsel. Typing up his notes night after night while working at Sing Sing, Conover turned them into a Pulitzer Prize–nominated book. If he hadn’t, certainly his PSTD would have been far worse.

But even today, Sing Sing draws Conover back across the line he stepped over many years ago, with it shifting around here and there and undermining his peace of mind. Having sought to narrow the distance between people who often violently disagree, to illustrate the blind spot of reason, the filthy work of being both a guard and a journalist lingers.

“In the dreams, I’m almost always a prisoner myself, not a guard,” says Conover over the phone, his voice always a little distant. “And part of the nightmare I’m involved in is the need to get out of that prison because I’m not supposed to be there. I’m not serving a just punishment. I’m there mistakenly.”

Suddenly, he pauses as if to stop his thought, as if reluctant to say it aloud to a stranger. “And so, so in a way, Habib’s situation goes to the root of some of my worst fears about prison: that a person, that I — that any of us — can end up there wrongfully and have to endure.”

Though Nnamdi Okonkwo was displaying his sculpture at America’s top black fine arts show, he criticized the event and its audience — even the very idea that “black art” exists.

“I have some problems with shows like this,” said the Nigerian-born sculptor, who was showing his work at the annual Black Fine Arts Show in New York in February. “The majority of people who come here are looking for art that reflects African American history. History becomes part of judging whether a picture is good.”

Okonkwo’s work probably doesn’t fit easily into that story. His bronzed figures of plump females represent the veneration of womanhood, he explains on his website, and were inspired by his wife and mother, not by black identity issues. “Ninety-nine percent of what I do as far as exhibiting my work does not concern [being black],” he said.

The success of Barack Obama’s presidential campaign has rekindled all kinds of debates over race, and not just in politics. Headlines and TV broadcasters ask:

“Is Obama black enough?”

“Is America ready for a black president?”

“Does race matter anymore?”

A parallel debate in the arts sometimes leaves black artists feeling pressured to produce work that reflects African American history and identity.

“There is no such thing as ‘black art,’” argued Josh Wainwright, the producer of this year’s Black Fine Arts Show, the major annual U.S. event showcasing art by Africans and African Americans. The show was begun in 1997 to address complaints by black artists that the art world marginalized and ignored them.

Asked why there were so few black artists represented in major art galleries, Wainwright, who is black, said he had “a pretty good idea why, and it’s called racism.”

Yet others argue that categorizing the work of African and African American artists as black art is a matter of practicality and salability.

“This is an audience genuinely interested in what African American artists are producing,” said Tony Decaneas, owner of Panopticon Gallery of Photography in Boston. “But as a dealer, I’m torn between putting up work that people will buy, and displaying works that have integrity and are fresh.” Human interest pieces and photos of recognizable figures sell best, but he tries to balance those with lesser-known work.

“There is a disconnect, even in the art world … for black artists who are not necessarily putting out what black people might want to see,” said writer and cultural critic Frank León Roberts. Yet, he said, white audiences are “eating up” avant-garde black art often ignored by black audiences.

The expense of buying original art could be a factor. “I think that, as a community, black audiences would gravitate towards works with black actors and themes related to the black community, so long as it’s actually affordable,” Roberts said.

Sometimes art, music, and theater produced by black Americans “is reduced to the question of how can markets best facilitate getting black butts into seats to watch black people perform black things and black comedy,” said Tavia Nyong’o, a professor of performance studies at New York University. “That then turns blackness into a commodity.”

Painter April Harrison considers her art an expression of personal memories and universal emotions, not black identity.

“My paintings are about love and spirituality,” she said. “My main theme is family bonding, taking you back to a time when love meant something.” Harrison’s work is dreamy and colorful, often depicting children, family members embracing, and other scenes from her home in Simpsonville, South Carolina. Her gallery show “Southern Comfort/Southern Discomfort” in 2007 juxtaposed her images of black Southerners with those by painter Charly Palmer.

Palmer’s paintings are full of sorrow and frustration, anger and hope: several incorporate signs from the segregation era, like “Waiting Room for Whites Only” and “Entrance Colored.”

“I don’t think there is any type of ethnic art,” Palmer said in a phone interview from his home in Atlanta. “Our subject matter just happens to be African American.” The impulse towards labeling things “black art” is a sign that “American society wants to put all artists in a category.”

“When it comes to my art, I paint African Americans, but I’m really painting the American experience,” he said. The idea of “black art” is a sad legacy of racism in the United States. “It goes back to the history of America, when Europeans brought in the Africans as slaves,” he said. “The need for separation has been there from the beginning.”

Although he won’t turn 18 until August, Minnesota high school senior Josh Bernick participated in his state’s Republican Caucus.

“For the first time in my life, I actually feel like I have some authority in the world, and don’t just have to sit back and watch things happen,” said Bernick, a student at Henry Sibley High School in St. Paul.

Bernick is in the lucky minority: Fewer than 20 states let 17-year-olds who will be 18 by Election Day vote in the primaries.

Political parties and state attorneys general usually make that call — and states can be reluctant to lower the age bar.

“If you start making exceptions, where are we going to draw the line?” wondered North Dakota Secretary of State Al Jaeger, who said he would be reluctant to change the law in his state, as it would raise questions about who could vote in other elections. “We do have the presidential primary race to think about, but we also have city elections in June, and should 17-year-olds be able to participate in those?”

No, Jaeger argues, because the U.S. Constitution says “that to be a qualified voter, you have to be of age, which is 18 years old.”

Yet decisions banning 17-year-olds have sometimes crumbled under legal scrutiny. And in states that ban the practice — such as California and New York — some teenagers are irate.

“There is no reason why a person who will be 18 by November 4th, and can cast a ballot in the election, shouldn’t be able to cast a ballot to decide who should be their party nominee,” argued Rebecca Steiner, a senior at San Dieguito High School Academy in San Diego, California.

“I’m clearly informed enough about the issues,” said Steiner, the captain of her school’s debate team. “I read the L.A. Times and many online news sites every day, and my friends and I have political discussions on a regular basis.

“It should be the same rules for political parties in every state — either all 17-year-olds should be able to participate, or none should,” she contended.

“I already know I’m voting for Barack Obama,” said Jessica Wong, a senior at the New York High School for Math, Science, and Engineering. “And if I know I want to support the Democratic candidate, I should be supporting him in the primary, not just in November.”

Too, she said, as a member of a political club, the Junior Statesmen of America, she participates in weekly politics discussions.

“That’s a lot more than many adults I know talk about it.”

A lawsuit earlier this year persuaded Maryland to restore voting rights to some 50,000 teens who will turn 18 by November 4th.

Student Sarah Boltuck, then 17, and her parents sued the Board of Elections, in a case that re-established voting rights for teens in that age group.

Though Maryland’s attorney general had found 17-year-old voting unconstitutional, based on a Court of Appeals decision on early voting, opponents who argued that the legal reasoning was flawed prevailed, according to FairVote, a not-for-profit that advised the Boltuck family on the suit.

Publicity surrounding the case also ended up more than tripling the number of 17-year-olds registering to vote in Maryland by primary time, to 10,000, from about 3,000 a month before, according to FairVote representative Adam Fogel.

“It just really shows how engaged young people are, and how they want to participate,” Fogel said. “Voting is habit forming; if they are voting now, they will most likely be voting for life. I almost guarantee 99 percent of 17-year-olds voting in the primaries will be back to vote in November.”

Rock the Vote, which encourages young voters to register and vote, has expanded its campaign to high school seniors.

“We recognize the importance of 17-year-olds who will soon turn 18, and work to engage, educate, and inform that group,” said Rock the Vote representative Shavonne Harding.

Rock the Vote sponsored a pre-caucus “Rock the Caucus” event in Iowa, generating buzz via Facebook, and organizing mock caucuses in Iowa high schools. Record numbers of young voters ended up participating in the Iowa caucuses.

Bernick found his experience enlightening.

“I would say I’m very informed after attending the caucus,” he said. “Whenever I discuss the election with my friends now, I feel like I definitely have the edge.”

We asked contributors and readers to answer this question, which refers to the U.S. Constitution ban on a “religious test” to hold public office in America. The question could be answered as narrowly focused or as generally as desired, touching on the interplay between religion and politics in American society — what’s good and what’s bad about it.

Here are their responses. Join in and add your comments and opinions. What do you think?

Larry Jaffe , writer and Poet Laureate for Youth for Human Rights

(Los Angeles, California)

From the United States Constitution, Article VI, section 3:

“The Senators and Representatives before mentioned, and the members of the several state legislatures, and all executive and judicial officers, both of the United States and of the several states, shall be bound by oath or affirmation, to support this Constitution; but no religious test shall ever be required as a qualification to any office or public trust under the United States.”

In my humble opinion, we have lost the meaning of religion, and those who “swear” by their faith believe more in dogma than the spirit. Thus, “religious test” would not even be an accurate statement given today’s standards. It is not religion we see mixed with politics, but dogma. It is not appreciation of God or spirit, but a belief system one must adhere to in order to belong to the “winning” side. Religion, in the truest sense of the word, is a set of beliefs concerning the cause, nature, and purpose of the universe, and often containing a moral code governing the conduct of human affairs. Politics of late, and perhaps always, certainly lacks moral code; simply witness the latest presidential primaries.

Furthermore, religious tolerance, perhaps one of the most important aspects of being religious, is all but abandoned. It is important to treat another’s religion as you wish yours to be treated. We have seen that when religious dogma mixes with politics, we lose all sense of religion.

Ryan Fuchs, mechanical engineer, blogger (Minneapolis, Minnesota)

The religious views (or lack thereof) should be no more relevant to their office than their sex or the color of their skin. The drafters of our Constitution understood this and bothered to state exactly that quite clearly. Many voters, however, are happy to be comforted with the knowledge that someone thinks as they do beyond the pertinent issues. In order to gain sway with this group, a candidate will advertise their religious beliefs. This has become the norm in elections of late. So much so that a growing number of people think the Constitution should be altered to make faith in a god necessary. I think that’s as silly as the desire to teach “creationism” in public schools. You’re free to have faith in whatever you choose. So am I. And so is anyone running for a public office.

John Amen , writer, musician, and founder and editor of The Pedestal Magazine (Charlotte, North Carolina)

Well, in theory politics and religion aren’t supposed to mix; i.e., a politician ought to be able to run a successful campaign regardless of his or her religious leanings. But we know that isn’t the case in America, at least currently. Bottom line, you’re not going to get elected to any significant office in America unless you espouse Christian principles. Clearly this is the case as far as getting the Republican vote but, in the end, I think it’s true with the Democratic vote, too. If you’re not a “Christian,” you’re fundamentally “the other,” regardless of all the PC talk, etc. This might change at some point. I mean, we’re looking at having a woman or African American in office, so that’s huge progress. Perhaps we’ll experience progress, too, in the relationship between politics and religion. But right now, if you espouse too loudly anything that departs from what’s considered essentially Christian, you’re probably not going to get very far.

Shawn Sturgeon, writer, author of Either/Ur (The River City Poetry Series) (Denver, Colorado)

There has always been an unofficial religious test for political candidates in the United States, since in the broadest terms, religion is concerned with the morals and values of a community. The question that challenges each generation of Americans is this: Who will write the test? We find the nature of the conflict over religion in American political life in two contradictory mottos engraved on the money we spend daily — “In God We Trust” and “E Pluribus Unum.” The first motto represents one way of deciding who writes the test: Let a single group with a sincere but narrow ideology determine the candidate who best represents “the good life” as they understand it. The second motto represents another approach: Respect differences of opinion and practice while achieving a consensus that “the best life” excludes no one. Personally, I favor the latter approach, but what does a poet know? Now I need to get back to chasing beaches and flowers.

Pris Campbell, writer , clinical psychologist (West Palm Beach, Florida)

If we’re talking theoretically, yes, of course they should. A candidate should be judged on his or her qualifications, alone. That’s not the way voters’ minds work, though, and sometimes with good reason. It’s only human nature to look at a candidate’s beliefs/religious associations, since we feel, at some level, those two things could play a role in political decisions. Take the flap with Obama’s minister, for example. When I saw the videos of him denigrating white people, calling us the U.S. of KKK, saying that 9/11 was a punishment … well, to know that this man was like family to Obama floored me. It also dramatically increased my leeriness about his potential presidency. A white minister could never be televised making racial statements and not damage a close political friend in the process. Obama has only said that his friend had the right to say what he thinks (which he does), but he’s not gone further, as of this writing, to say he disagrees adamantly with the anti-white statements.

The flap with Obama’s minister is even worse than when John Kennedy was running for office. The outcry was “Do we want the Pope to run our county?” I still remember that campaign. People were terrified over that issue. Now, if a Catholic ran, it would be a moot point. I wonder how a candidate who was close friends with a TV evangelist telling us he’s been called by God to collect money from little old ladies living on tiny SS checks would fare? Bottom line, beware of your bedfellows. Religious or not, they may kick you in the kneecaps when you least expect it.

David Paskey, graphic designer and songwriter (Chicago, Illinois)