It is 6 a.m. Monday. The winter sun has not yet risen, but slowly, shadows of men flit through the dark. They gather against the bare rock walls of Pare de Sufrir Church in Woodside.

And in the morning emptiness, the laborers of Roosevelt Avenue begin their daylong vigil for temporary work.

A giant white cross hangs on the corner of the church, obscured by the elevated tracks of the No. 7 line that runs along Roosevelt. At 8:30 a.m., more than 50 Latino men, mostly from Ecuador, gather on all four corners of the intersection and wait.

For day laborers, New York City has long been a mecca where pay was good and work plentiful, according to Oscar Parades-Morales, executive director of the Latin American Workers Project in Jackson Heights. As the rest of the nation went through the subprime mortgage crisis, workers from as far off as California converged on the city looking for work, says Parades-Morales.

But in recent months, the construction industry has entered a slump. New York state has lost 2,000 jobs in construction since September 2007, according to the Department of Labor. A report released by the New York Building Congress, which represents the construction industry, expects 30,000 jobs to be lost in the city by 2010.

On Roosevelt, the workers are already facing difficult times. Last October, police arrested 10 laborers for obstructing the sidewalk at 37th Avenue and Broadway, three blocks east of the intersection. The incident was unusual, but has left the men apprehensive.

Below the white cross is a short, middle-aged, undocumented man who refused to reveal his name. “Jose” crossed into the United States from Ecuador seven years ago with his family.

“Running. Running [through] El Salvador, Guatemala, Mexico,” he says. “Maybe all day here.”

Jose is desperate for work. He needs money for child support payments to maintain visitation rights to his daughter and son.

Jose’s friend, “Jorges,” who also declined to identify himself, has his family in Ecuador. He came to New York City in 1986 when Ronald Reagan was president. He is taller than the others and is dressed in a brown leather jacket and a navy blue “NY” cap turned backward on his head.

“My baby,” he says of his nine-year-old son as he pulls out a passport-size photo of a black-haired, chubby boy from his wallet. “My wife.” He displays a photo of an unsmiling woman.

“No job yesterday. This year, no job,” he says. He has filled out an application for work in Manhattan, but no one calls him. So he ends up with the uncertainty of Roosevelt, waiting for contractors who pay less than minimum wage and hire one person for jobs that require at least two workers.

The men wait at a street corner until a contractor pulls up looking for day laborers. The men come cheap and one will do the work of many Americans. They are uniformly dressed in caps, sweatshirts, and blue jeans, and tote black knapsacks. There are a disproportionate number of mustaches in the crowd, a sign of manhood in Latin American nations.

At 9 a.m., the men stand around, doing nothing. Some sit on the litter-strewn sidewalk in their baggy jeans. Concrete is a natural conductor; it sucks the warmth of the human body. The younger men choose to be in the sunlight farther down 69th Street, but the older men stay under the cold shadow of the El. When a car pulls up, the extra seconds it takes to hurry back to Roosevelt can cost them the day’s job.

Some talk. Others don’t. Women walk by without sparing them a glance. The day laborers do not seem to notice. They are transfixed by the flow of traffic. When innocuous vans pause on the street, the men stare and wait for them to pull to the curb. A car honks on Roosevelt. Every man turns his head toward the car, but it doesn’t stop.

A green sedan pulls up to the curb. Three men race up to the car, hopeful. The lady asks for directions; the men help her out.

Every time I talk to Jose and Jorges, men dart across Roosevelt, thinking I’m hiring for a job. “You want worker?” they ask.

“They are like bee. Everybody will sting the car. They are like, grab the person,” says Pamela Plum, the owner of Color and Cut, a salon on 69th and Roosevelt, outside which the laborers wait.

The men switch positions and move from the wall of the church to the edge of the sidewalk. One man in a denim shirt is barely as tall as the mailbox he leans against.

At 9:37 a.m., a gray car pulls up. Three laborers go up to it and stand at attention. The driver gets out and talks on the phone, gesturing furiously. He then haggles with the laborers. The three get hired.

The going price for labor is cheap. It used to be $120; now they are lucky if they get $80 for a whole day’s work.

George Memdoza, 25, has blue-green eyes, fair skin, and a protruding belly. He came from Ecuador 10 years ago and lives with his mother.

He got a job moving furniture Sunday at 9 p.m. He finished work at 5 a.m. For eight hours of work, he was paid $80.

“No job is easy,” he says. “There was only me. Moving everything. Bed, cabinet, chair. Right now, my eyes very sleepy.” He came directly to Roosevelt after that job. “No go back to house,” he says.

Memdoza is harsh on the police. “Police come to intersection, ask if we have coke, marijuana. I’m no <i>narco</i>. Police <i>no comprende</i>,” he says.

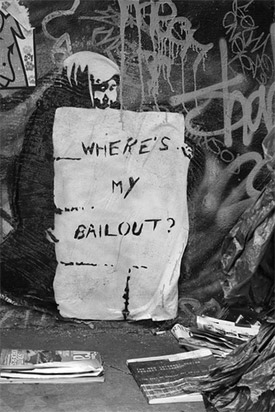

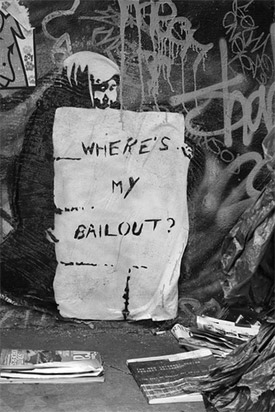

This erratic work is the only source of income for these men. They are undocumented and unskilled, and the economic recession has snatched away too many jobs.

“The economic crisis is horrible,” says Parades-Morales at the Latin American Workers Project. “I have workers on the street who don’t find jobs for three, four months.” Parades-Morales tells of a man who got seven hours of work one week, and then two hours of work the next.

Many fall prey to unscrupulous contractors who do not pay at the end of the day, according to Parades-Morales. The men have no Occupational Safety and Health Administration training, a fact illustrated by the fake Nikes the men wear. Too few are in heavy-duty construction boots. In 2008, 21 men were killed in construction-related accidents in New York City; 17 of them were Latinos, according to Parades-Morales.

At 10:30 a.m., a plain white van pulls up. Men dart into traffic to get to the other side of the intersection, Jorges among them. About 20 cluster around the van.

“This guy, everyday he come here, take four, five people for delivery,” explains Jose, Jorges’ friend.

Jorges is not hired. The younger men are cooler, the older ones more jittery. They have greater family obligations. They have kids and must send money home. Jorges unfolds a yellow Western Union receipt and displays a $30 deposit to Ecuador proudly. He says that he needs a job today to pay his $100-per-week rent.

The small man leaning against the mailbox is at the edge of the sidewalk, anxiously scanning traffic.

By 10:37 a.m., most conversation has ceased. The El thunders by constantly. Many younger men give up and leave. The older men hang on.

At 11:30 a.m., in a Starbucks 10 blocks down the road, two elderly white men discuss the day laborers. “I remember postcards where the authorities fight the illegal immigrants [from Latin America] off because once they land, they start sucking off the public welfare system. … They come here and find heaven.”

At 2:30 p.m., there are two men outside Pare de Sufrir. Everyone else has left. Jose and Jorges waited for five hours but they finally gave up.

One week later in November, the men complain about the residents of 69th Street. Some men had drunk beer and created a racket overnight on 69th and Broadway, for which the day laborers had been blamed.

“What we do? We trying to live,” said Jose.

As night falls, the brothels along Roosevelt traditionally come alive as day laborers seek female company away from home and family. But these days, no one goes, according to Gustavo Gomez, a day laborer with family in Ecuador. Money no longer flows along Roosevelt.

- Follow us on Twitter: @inthefray

- Comment on stories or like us on Facebook

- Subscribe to our free email newsletter

- Send us your writing, photography, or artwork

- Republish our Creative Commons-licensed content