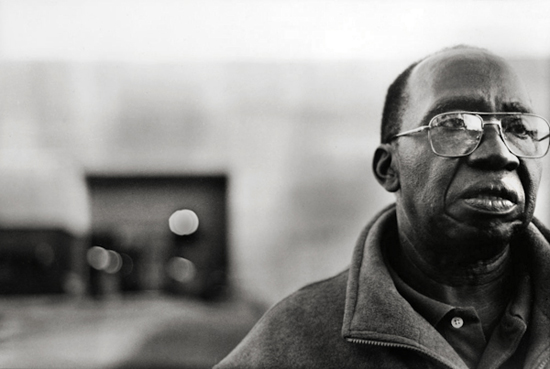

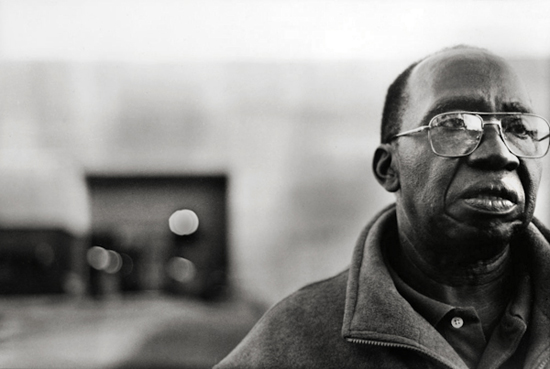

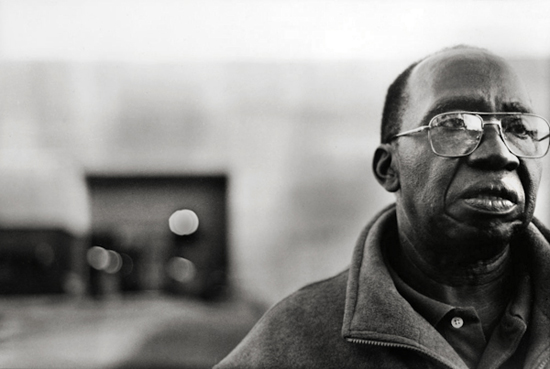

At 7 o’clock on a cool fall morning, Matthew Kongo steps out of the Spencer Press printing plant and into daylight. The air coming off the ocean to the east is moist, the world quiet compared to the printing room inside where Kongo, 65, has been working the night shift. He wears a gray fleece jacket, dark jeans, and heavy leather work boots. Large thin-rimmed glasses balance on his wide nose, magnifying soft, sleepless brown eyes.

Kongo is still for a moment, looking out into the company’s parking lot as if taking in the world anew. During his 12-hour shifts, he stands at a computer terminal, moving paper into the production line with a large crane. After a spate of recent layoffs, he has been manning two cranes at once to increase efficiency. It’s difficult, repetitive work, especially with an injured back, a lingering reminder of his previous life in Sudan.

Kongo spots his coworker Hassan Ahmed’s Toyota four-door pulling around to the worker’s entrance. He slowly walks over to the car and gets inside. Ahmed is a refugee from Sudan, as is Kongo, although they come from far corners of the large country. Ahmed is from Darfur in the west; Kongo is from southern Sudan.

During the drive back to Portland, Maine, half an hour to the north, the two men speak of their home country and the problems there. They talk about ethnic and religious conflicts, about disputes between the central government and outlying areas, about the brutal wars that have engulfed the country for most of their lives. Solutions to Sudan’s problems seem hard to come by, and the causes almost too numerous to count.

Ahmed drops Kongo off at his home, an apartment in a three-story Victorian near the heart of Portland. Kongo climbs the stairs to the third floor where he and his family live. His wife Rose is about to head off to her job at Maine Medical Center, so they have only a brief moment together before she leaves. Their 10-year-old daughter Nancy, her hair tightly braided, is just finishing breakfast and is ready for Kongo to take her to school.

Kongo slowly makes his way back down the stars as Nancy runs ahead and jumps into the backseat of his Dodge sedan. Kongo then drives her across town to Cathedral School, where she has recently started classes. She had been going to the local public school, but was recommended by her teachers to go to a private school where she might have more opportunities. Kongo and Rose are hopeful that Nancy will go to college one day. Her sister Catherine, 19, arrived in the United States as an adolescent, and has had a tougher time adjusting to life in her new home. She recently graduated from high school and is now babysitting for relatives.

After dropping Nancy off at school, Kongo returns home for breakfast and a few hours of sleep. But he has many things he needs to do today. There is a meeting with fellow refugees to discuss housing options, a stop at Hannaford for the family’s groceries, and an upcoming community event to plan. His next shift at Spencer Press starts again tonight at seven.

*****

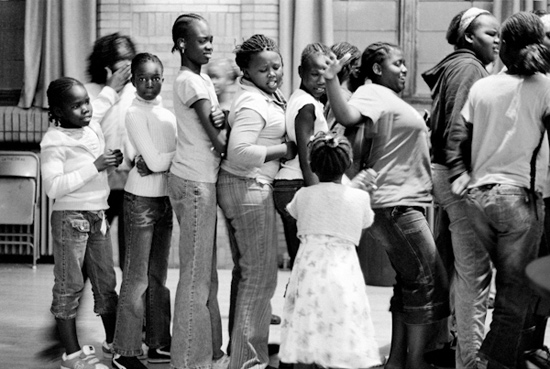

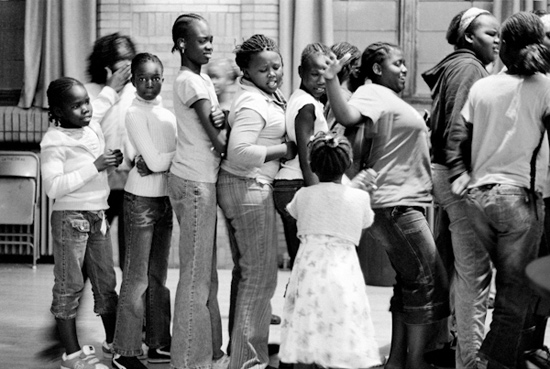

The door opens and cold air rushes into the auditorium. Two young children enter and make their way to one of the round tables where other Sudanese children sit. Two tables of adults are among the children. Between the stage and the tables, a small group of boys and girls in jeans, hooded sweatshirts, and wool sweaters walk around a circle of chairs, while R & B blasts from large speakers on either side of the stage.

Kongo, dressed in a striped charcoal suit, leans back in a folding metal chair, his body relaxed but his face serious. Deep wrinkles frame his pursed lips. The deejay near the stage hits a switch and the music abruptly stops. The children run to sit down, bumping against one another, some winding up on the hardwood floor. The sound of laughter erupts inside the room. A large smile flashes across Kongo’s face as he leans forward, his hands coming together in a single loud clap.

Tonight is billed as a “Back to School Night” by the Sudanese Community Association of Maine, which hopes to show these children how important education is to their new lives in America. Kongo is president of the association. Fifty children are present tonight — many more than last year — but there are few parents. It’s one of the main problems the association faces in trying to send these children to college one day. For so many Sudanese in Maine, life is little more than work, school, food, and sleep. There is hardly time for events like these, where parents can show their enthusiasm for school.

The youngest children, no more than four or five years old, chase each other around the room, while the women, wearing bright dresses and dark suits, sit at their table and speak in hushed tones. At the men’s table there’s talk of Sudan, Al-Bashir, United Nations troops, and the upcoming game: Patriots vs. Dolphins. Kongo is among them, standing up to shake the hand of every adult who walks through the door. Then he leans into a conversation and answers questions in a mix of Arabic and English. Rose sits at the women’s table and speaks to a Sudanese woman in her 60s, who has just arrived in the United States. Nancy listens attentively at one of the far tables with the rest of the children.

Nancy’s sister Catherine, in jeans and a fleece jacket, is the night’s emcee. After the games, she challenges the children with trivia questions: “Who is the president of the United States?”; “Who was the first president of the United States?”; “Who was the president before the current one?”; “Who is the president of Sudan?” A child raises her hand confidently, but when she’s called on she sinks into her seat, smiles, and loses her words. Most of the children know the answer to the first three questions, but the younger ones have trouble naming the president of Sudan. Several older children, sitting at their own table in the back, raise their hands. When called on, they intone, “Al-Bashir.”

In the last 15 years, Maine has attracted Sudanese refugees with its image of a slow pace of life and the absence of violent crime. There are over 6,000 living in the state, most of them in Portland. Kongo came to Maine because he thought it would be a good place to raise his children. Unfortunately, many refugees — Kongo included — have found Portland to be a typical city with its share of drugs, racism, and hostility to immigrants.

Excitement pulses through the room as trays, bowls, and boxes of food emerge from the kitchen: okra with stewed beef, eggplant in peanut sauce, salad greens, cucumber and tomatoes, white rice, macaroni and cheese, potato chips, meatballs, and pepperoni pizza. The children are reminded to have a little of everything, to not eat just one kind of food. They line up single file, a train of children, front to back, waiting impatiently for their turn as the adults move through the line first.

When dinner is over, Kongo slowly stands and walks to the front of the room. He takes the microphone and speaks to the children in English. He urges those who have come alone to go straight home and tell their parents all about tonight. And he encourages everyone to tell their Sudanese friends who are not present how much fun they had and to come to the next event. He wishes them all a good night, and then puts the microphone down and makes his way back to his table. As children leave, Kongo joins the men folding and stacking chairs on the side of the auditorium.

*****

Sudan, Kongo’s homeland and the largest country in Africa, sits south of Egypt on the Red Sea and covers an area of 1 million square miles — about one-third the size of the United States. Sudan has been in a state of civil war for most of the last 50 years, and as a result, Sudanese refugees have been forced to resettle throughout the world. The conflicts between the north and the south — and the recent conflict in Darfur, which began in 2003 — have complex historical antecedents that cannot be explained simply (as they often are) as a war between black Africans and Arabs or between Christians and Muslims. But however complex, Kongo is quick to point out that race and religion play an important role in the civil wars.

Sudan is a diverse country, with more than 140 native languages, 19 ethnic groups, and many local religions. Christianity arrived in the fourth century and Islam followed several hundred years later, brought into the Nile region by Arabs from the Middle East. The Arabs, who came to dominate the north, forcibly spread Islam throughout much of the area. They began programs to centralize authority in Khartoum, Sudan’s capital, while marginalizing outlying areas. They enslaved black Africans and extracted resources from the south, including ivory and, more recently, oil. Most of the country’s arable land and natural resources are located in the south.

Kongo was born in Yei, a provincial headquarters on Sudan’s southern border with the Belgian Congo (now the Democratic Republic of Congo) and Uganda. He was born on December 8, 1944, 12 years before Sudan gained its independence from the British and 11 years before the south’s trouble with the north began in earnest. The British had co-ruled Sudan as a colony from 1899 until 1955 with Egypt. In practice, however, Sudan was ruled as two separate states: a northern Islamic state and a southern Christian state.

When Kongo was a boy, a mutiny by disaffected southern soldiers led the British to rush plans for Sudanese independence. They granted formal independence on January 1, 1956, before a permanent constitution could be signed into law. Debate about southern autonomy and federalism were relegated to the future. With the south’s concerns unaddressed, a civil war broke out in the form of a guerilla conflict that turned into a conventional war. Aside from a 10-year break from 1973 to 1983, which did little to ameliorate the underlying causes of the first war, war has continued for 50 years. A peace agreement signed in January 2005 signaled a chance for lasting peace in southern Sudan, just as the fighting in Darfur escalated.

Kongo was born into the Mundu, one of the many black African tribes indigenous to southern Sudan. He was raised in the Catholic Church, and moved when he was 18 to El Obeid, a town southwest of Khartoum, to start high school at the Comboni Catholic School. But after only one year he decided it would be best to leave Sudan; the civil war had intensified to the point where he feared for his life. The borders in the south were closed. The only way out of Sudan into exile would be to make the dangerous journey through the north. He telephoned his parents and told them he was about to leave the country. They gave him their blessing and said, simply, “Go in peace, and let God guide you and bless you.” He would never see them again.

Ready to make the journey out of Sudan, 19-year-old Kongo was joined by one of his teachers, Alfonse Abugo. They packed their bags and took a train to Khartoum, where they boarded a bus to the eastern city of Kassala, on the border with Ethiopia (now part of present-day Eritrea), where the flat yellow desert stretches to the base of gray, rocky cliffs that rise 1,000 feet over the city. From Kassala they walked into the wilderness toward the border. Alert to the possibility of trouble, the two men buried their bags in the sand under a bridge before entering a small nomadic village. There, among huts thrown together with mud, canvas, and tin, they were met by several men with friendly gestures, and were given milk to drink. They took a seat on a mat outside one of the huts, where they rested.

After an hour filled with quiet conversation, a man appeared wearing a white jelabia — a long flowing shirt that reaches down past the knees — over white baggy pants. A long, curved sword hung from his waist. Their luck seemed to be up.

The man began interrogating them, asking them why they were on the border, about to leave the country. Kongo lied. He told the man that they were on their way to Asmara, in Ethiopia, for a weekend of shopping. The man became more and more suspicious, and asked them about their faith. He accused them of being antigovernment because they were southerners and Christians. He accused them of leaving the country to join the rebels. They denied the charges.

As the man became increasingly agitated, one of the other men from the village stood up and told the travelers, “Please know that I am not going to be one of those that may harm you. And let your blood not touch me or my children.” Incensed by the outburst, the hostile man attacked this man, their defender, saying that he was antigovernment. “You are a traitor,” he yelled.

While the Arab men argued, Kongo leaned over to his teacher and said, “This is the chance. You start running.” Kongo was young, broad-shouldered, and strong. He was confident that he could ward off the men if they attacked, especially since they wore long, clumsy clothes that would keep them from running fast. “And never mind about whatever is happening to me,” he told his friend. “I will be behind to make sure that nobody runs after you.”

Abugo turned and ran toward the bridge where they had hidden their bags. A commotion ensued, and the agitated man chased after Abugo. Kongo rushed after the man and kicked his legs out from under him. He took the man’s sword and stood over him. The other men scattered as Kongo brought the sword — still in its sheath — up into the air and then down onto the man’s back with a dull thud. As the man cried out, Kongo ran off into the desert, joining his teacher under the bridge, where they spent the night. In the morning, they walked several miles down the road before reaching a roadside bus stop, where they got on a bus that took them to Asmara. Kongo would not return to Sudan for 26 years.

*****

The aisles of Portland’s Hannaford supermarket are brimming with food. Kongo is in the cereal aisle, leaning into his shopping cart as he makes his way to the back of the store to pick up a carton of orange juice. He moves through the store slowly, methodically.

In the meat section, Kongo recognizes a West African immigrant in his late 30s. They shake hands and the man asks him about another member of the Sudanese community. Kongo explains that there have been two untimely deaths in the man’s family. The conversation switches directions, and the man says he knows of some jobs opening up at a local plant. He asks Kongo if he can pass the information on to the Sudanese community. “No problem,” Kongo replies.

Moving on to a new aisle, Kongo adds a box of tea and a package of sliced banana bread to his cart before heading to the customer service desk to send a remittance to his niece in Cairo, Egypt — the real business of his visit to Hannaford. Kongo’s niece and her three children, like many displaced Sudanese, are waiting in Egypt for their refugee status to be confirmed by the United Nations so that they can be accepted to a new home, most likely the United States, Canada, or Australia.

Kongo takes a Western Union slip from a pile and squints to read the instructions; he left his glasses at home. He leans on the table, his head close to the slip. After carefully filling out the form, he takes it up to the counter. “You’re missing a section,” says the young man. Kongo walks back to the pile of slips, takes another, and fills out the missing section.

Back at the counter, while Kongo waits in line, some change drops out of his pocket. “Sir,” a man behind him says, and points to the ground. A large smile flashes across Kongo’s face. He bends over to pick it up. “Thank you,” he says, before turning forward and resuming his stoic expression.

At the counter, the man looks over the form again. Everything seems to be correct this time. He spells out the name aloud while Kongo listens to make sure the money goes to the right person. “One hundred dollars,” Kongo says. “No, one hundred and twenty dollars.” The man turns to enter the information in his machine. “One hundred dollars for her rent deposit, twenty dollars for pocket money. One hundred dollars there is like five hundred dollars here.”

*****

The Kongo family lived in Cairo in 2000. They were four of the more than 414,000 displaced Sudanese there, many awaiting emigration to an unknown new home. Rose was the first to get a job, so she worked while Kongo stayed home with their young daughters.

Displaced persons seeking refugee status are required to register with the U.N. High Commissioner for Refugees within a week of arrival. After Kongo registered, he was given a date and time to return for an interview. He would need to provide the reason he fled Sudan and give evidence that he could not return. While many spend years awaiting refugee status, it did not take long for Kongo. His was an obvious case.

After escaping Sudan in 1963, Kongo lived in several East African countries, graduating from high school and then working for various firms before becoming the chief executive officer of a logistics company in Uganda. The company handled all of the exports for Uganda during a coffee boom, and Kongo reaped the benefits: cars, a driver, and a staffed house. But despite the plush life he had made for himself in Uganda, Kongo yearned to return to Sudan, his home.

So in 1989, three years after marrying Rose, Kongo moved his family to Juba, the capital of southern Sudan, about 100 miles from his native Yei. He accepted a position as a relief and agricultural coordinator for Sudan Aid, a nongovernmental organization working with internally displaced people in southern Sudan during the height of the second civil war. As government soldiers shelled the towns of southern Sudan, scores of people made the journey to Juba to live in camps on the outskirts of town. Kongo arranged for aid to be distributed within the camps.

Then in 1999, without warning, Kongo was arrested and charged with aiding the rebels. He adamantly denied the charge, but was sent to a detention center anyway. Government officers interrogated him about his alleged involvement with the rebels. Interrogations in the prison involved psychological intimidation, beatings, and pressure holds. Kongo sustained a back injury that would not be treated until he reached the United States over a year later. The pain still has not totally subsided. Kongo refused to admit to a crime he had not committed, but the interrogations continued with no formal trial.

While he was imprisoned, Sudan Aid and the Catholic Church worked on his behalf. Their efforts paid off, and he was released a month after he entered prison, on the condition that he never reveal the details of his stay. He continues to keep his silence.

Knowing that he could be arrested again at any moment if he remained in Sudan, Kongo fled to Egypt with his family, leaving on a train in the middle of the night. After a year in Cairo, they were accepted into the United States and arrived in Portland on January 31, 2001.

*****

It’s Saturday night, and Portland’s many restaurants are full of patrons. As the night wears on, the tiny bars on Congress Street and the large, popular ones in the Old Port begin to fill up. Bands take the stage and music escapes through doorways into the cobbled streets.

Kongo sits on one of the couches in his living room. He leans back, letting his right leg extend straight out in front of him, his bare feet resting on the carpet. News from CNN flashes across a large-screen TV sitting prominently on a wooden entertainment center. Rebels in Darfur have scored a major victory against government soldiers in Sudan. Kongo watches attentively. With little time to read, he has turned to CNN to stay informed and learn about politics.

In the spring, Kongo’s political skills were put to the test when the Maine legislature considered a bill to divest the state’s retirement funds from Sudan. The Sudanese government uses much of its revenue for military expenditures, meaning that money invested in Sudan indirectly funds weapons used in Darfur. At the time, Maine had more than $50,000,000 invested in companies doing business in Sudan.

Several members of the Maine House and Senate were reluctant to vote in favor of the bill, so Kongo got in his Dodge sedan and drove to Augusta, the state capital, to lobby with other Sudanese refugees on behalf of the bill. He spoke to the opponents, explaining the situation in Sudan. He made the drive three times. Later, when the bill came to a vote, it passed unanimously. In April, Kongo was invited to stand beside Governor Baldacci as he signed it into law.

Kongo calls to Nancy, who is in another room doing homework while her older sister watches TV. She opens the door, and R & B follows her out of the room. Kongo asks her in Arabic to put on hot water and make a cup of Milo, a chocolate drink popular in the developing world.

“In the time I’ve been in the United States,” Kongo says, “I have never once been to a beer bar. I have never had one beer outside of my home. There just isn’t any time.”

Nancy returns with a cup of Milo on a saucer, and sets it down on the coffee table in the center of the room. Rose is working at Maine Medical Center until 1 o’clock tonight, assisting doctors in the emergency room. Nancy returns to her room through the kitchen. The girls do not like CNN, so they usually watch their own TV while Kongo takes in the world’s events by himself. Sometimes, particularly when professional wrestling is on, they all sit together in the living room and watch.

Across Portland, on Munjoy Hill and in Kennedy Park, Sudanese children are watching Egyptian movies on satellite TV; they are watching American sitcoms with their siblings, and they are playing games with neighborhood friends. Their parents are coming home from work, or are heading out the door on their way to work, or are in the next room studying for a college class. Some are sitting next to their children, telling stories. There are moments of relaxation.

“I’m becoming too old to work on my feet all the time,” Kongo says meditatively. “Perhaps I will go back to school. Political science. Or maybe economics. You need a degree to work in an office in this country.” There’s a pause, and then a smile. “I might start my own business. I ran a transportation business before, in Africa. I could buy a truck, an 18-wheeler. I know a man who would drive it.”

Tomorrow evening at 6 o’clock, Kongo will pull on his work boots and drive to Hassan Ahmed’s house to pick him up. The two will then drive to Spencer Press and start another workweek. Kongo will stand at his computer terminal for another 12 hours, moving rolls of paper into the production line.

For now, though, he sits back on his couch and contemplates the possibilities.

Kyle Boelte and Anna M. Weaver are documenting Sudanese refugee life on four continents. More information can be found at www.acrossfourcontinents.org.

Kyle Boelte

Dear Reader,

In The Fray is a nonprofit staffed by volunteers. If you liked this piece, could you

please donate $10? If you want to help, you can also: