How did America go from a president elected after urging voters to forget about his religion to, 40 years later, a president who made religion central to his campaign, declaring Jesus as his “favorite philosopher”?

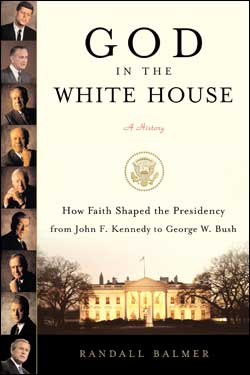

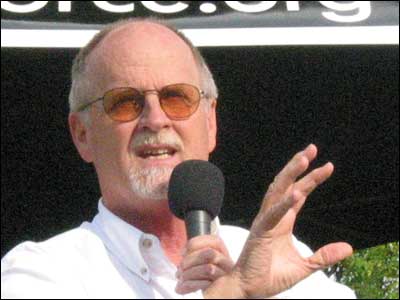

Randall Balmer, a professor of American religious history at Barnard College and editor-at-large for Christianity Today, tries to answer this question in his 12th book, God in the White House: A History: How Faith Shaped the Presidency from John F. Kennedy to George W. Bush.

Balmer, who describes himself as a left-leaning evangelical Christian — his last book was Thy Kingdom Come: How the Religious Right Distorts the Faith and Threatens America, talked with InTheFray about the role of religion in presidential politics, the “abortion myth” in the rise of the Religious Right, and why religion is best left “on the margins of society, not the councils of power.”

Interviewer: Jonathan Mandell

Interviewee: Randall Balmer

God in the White House ends before the 2008 presidential campaign begins. What role has religion played in this campaign, and how does it differ from previous presidential campaigns?

The most intriguing element of the 2008 presidential primaries was the attempt by Mitt Romney to become the Republican nominee. He’s not the first Mormon to run for the White House, of course. Joseph Smith, the founder of Mormonism, made a run in 1844, though it was cut short by his assassination at the Carthage jail. And Orrin Hatch, Republican senator from Utah, made a brief try in the 2000 campaign season. The most remarkable precedent, however, was Mitt Romney’s father, George, the governor of Michigan, who was the early favorite in the Republican primaries in 1968.

I happened to be living in Michigan at the time, and I have no recollection whatsoever that George Romney’s Mormonism was an issue in 1968. His candidacy eventually imploded when he professed to have been “brainwashed” about Vietnam. In the course of doing research for God in the White House, I looked back at the 1968 campaign to see if somehow I’d missed it, but it simply had not been an issue.

But 40 years later, it became clear — to everyone but Mitt Romney, it seems — that the former governor of Massachusetts would not be given a pass on his Mormon faith, unlike his father.

Why do you think there was such a difference in the reaction to George Romney’s and to Mitt Romney’s Mormonism?

What I call the “Kennedy paradigm” of voter indifference toward a candidate’s faith prevailed in American presidential politics from the 1960 campaign through the 1972 campaign. But then Nixon’s corruptions set the stage for Jimmy Carter’s out-of-nowhere run for the presidency in 1976.

I also think, frankly, that Mitt Romney played it all wrong. He went to the George Bush Library in College Station, Texas to give what reporters were calling his “JFK speech.” But Romney was handicapped in that the two central arguments that John Kennedy used in his 1960 speech to the Greater Houston Ministerial Association were unavailable to him. In that memorable address, Kennedy unequivocally affirmed his support for the separation of church and state, and he renounced all government support for religious schools. Because Romney was pandering after the votes of the Religious Right, however, whose leaders believe in neither of those foundational principles, Kennedy’s arguments wouldn’t play.

I think that a better model for Romney would have been Joe Lieberman, not JFK. When Al Gore named Lieberman to the ticket in 2000, he faced a flurry of questions about his Judaism. Was he Orthodox or merely observant? Why didn’t he campaign on the Sabbath? Unlike Romney, who grew testy whenever anyone asked him about his faith — “I’m not a theologian; I don’t speak for my church” — Lieberman faced those questions directly and without evasion.

What did you make of the surprising success of Mike Huckabee, a candidate whose day job had been as a Baptist preacher? How unprecedented was this?

I’ve tried to determine the last time an ordained minister made it this far in the primaries. It was, I believe, Jesse Jackson in 1984. Pat Robertson made a run at the Republican nomination in 1988, but he resigned his ordination just before announcing his candidacy.

But Jackson didn’t emphasize his religion, and Robertson didn’t have the electoral success that Huckabee had for at least part of the primary season. When is the last time we had such a successful candidate who connected the dots between his religion and his politics in such boldface?

The last time, I think, was Jimmy Carter. I make the case that Carter was the only president we’ve had in the last half century who actually sought to govern according to the principles he articulated in his campaign for the White House.

You also point to the irony that his presidency led, in a way, to the rise of what you call the Religious Right — the re-introduction of evangelicals into worldly affairs after more or less hibernating for 50 years after the Scopes evolution trial of the 1920s.

One of the great paradoxes of presidential politics over the last half century is that evangelical Christians, who helped propel Jimmy Carter to the presidency in 1976, turned dramatically against him four years later.

What became clear to me, as I was working through the archives at the Carter Center, is that Carter himself was utterly blindsided by the Religious Right in the run-up to the 1980 election. He didn’t see it coming. When he finally hired a religious-affairs liaison — a Baptist minister — it was really too late.

You document what you call the “abortion myth” in the birth of the Religious Right.

To hear the leaders of the Religious Right tell it now, they became politically active in direct response to the Supreme Court’s Roe v. Wade decision on abortion, which was handed down on January 22, 1973. According to this scenario, these hitherto apolitical ministers reluctantly entered the political fray out of their own moral outrage over the Roe decision. These leaders of the Religious Right even characterize themselves as the so-called “new abolitionists,” in an effort to equate their opposition to abortion to the opposition of antebellum evangelicals to the scourge of slavery.

The truth, however, is rather more complicated. The Southern Baptist Convention, hardly a bastion of liberalism, passed a resolution at its gathering in St. Louis in 1971, calling for the legalization of abortion — a resolution reaffirmed in 1974 and again in 1976. When the Roe decision was handed down, several evangelicals, including the redoubtable fundamentalist W. A. Criswell of First Baptist Church in Dallas, applauded the ruling as marking an appropriate distinction between personal morality and public policy.

I call this the “abortion myth” because abortion had little — almost nothing — to do with the emergence of the Religious Right. The Religious Right did indeed arise in response to a court decision, but it was not Roe v. Wade. It was a lower court ruling in 1971 called Green v. Connolly, which upheld the Internal Revenue Service [IRS] in its ruling that any organization that engaged in racial segregation or discrimination was not, by definition, a charitable organization, and therefore had no claim to tax-exempt status. In the ensuing years, the IRS sought to enforce that ruling, and acted against various private “segregation academies” (schools founded in response to the Brown vs. Board of Education Supreme Court decision of 1954 that ordered public schools desegregated). The IRS also targeted a fundamentalist school in Greenville, South Carolina, called Bob Jones University, and it was this action that triggered the evangelical activism that became known as the Religious Right. Only later, in preparation for the 1980 presidential election was abortion cobbled into the political agenda of the Religious Right.

Your book makes clear that evangelical, Baptist, fundamentalist, Christian Right, and Religious Right are not all synonyms, as they may appear to be to the outsider. Could you explain the distinctions?

By no means are all evangelicals part of the Religious Right. It’s probably fair to say that a plurality, perhaps even a majority, of evangelicals list toward the right. But even that is changing, especially among younger evangelicals, who are increasingly concerned about such issues as global warming, the war in Iraq, and this administration’s persistent, systematic use of torture. They care little about issues of sexual identity, and they’ve grown weary of what passes for debate over the abortion issue.

As for nomenclature, I prefer the term “Religious Right” to “Christian Right” or other variants. Frankly, as a Christian, I don’t find much that I would identify as “Christian” in the actions and agenda of the Religious Right.

Are Baptists by definition evangelicals?

Historically, it’s probably fair to say that all Baptists were evangelicals in that they believed in the centrality of religious conversion, the inspiration of the Bible, and the mandate of evangelism. Today, however, some Baptist groups are more theologically liberal and would probably resist — even resent — being called evangelical. Having said that, I would argue that the largest Baptist denomination — the Southern Baptist Convention — is thoroughly evangelical.

You say that the reason why abortion and homosexuality became the focus of the Religious Right is that they could no longer focus on divorce.

When the leaders of the Religious Right embraced Ronald Reagan — a divorced and remarried man — as their political savior in 1980, they dropped almost immediately their long-held objections to divorce. Not that they began advocating divorce; I’m not suggesting that at all. But I went through the pages of Christianity Today, the flagship magazine of evangelicalism, to chart the frequency of articles condemning divorce in the 1970s and again in the 1980s. I forget the numbers, but the denunciations of divorce in the pages of Christianity Today dropped virtually out of sight after 1980.

You seem to write mostly about evangelical Christians when discussing the interplay between religion and politics. Are they by far the largest factor in the heightened mix? Where, for example, do Catholics — who reportedly make up 24 percent of the U.S. population — figure in this interplay?

The leaders of the Religious Right have been very effective in cooperating with conservative Roman Catholics on political issues, especially abortion. This has led to some political successes, although I don’t think the Religious Right has much to show for its activism over the past several decades, aside from judicial appointments. One of the things that I find fascinating is the extent to which politically conservative evangelicals have relied on conservative Catholics for their political ideology and their ability to bring intellectual heft to the Religious Right. It strikes me as no accident that George W. Bush’s appointments to the Supreme Court have been conservative Roman Catholics. That suggests to me that the Religious Right itself simply doesn’t have a strong “bench” of ideologues, so they look to the Catholics.

The cooperation between conservative Catholics and politically conservative evangelicals, however, has had at least one happy effect: The level of suspicion between evangelicals and Catholics has dissipated considerably. When I was growing up as an evangelical, for example, my parents told me that I would be disowned if I married a Catholic. Those prejudices may not have disappeared, but they have abated considerably.

In God in the White House, you write: “My reading of American religious history suggests that religion always functions best from the margins of society, not in the councils of power.” What do you see as the major pros and cons to the heightened attention to religion in politics in the U.S. as a whole and, in particular, in presidential politics?

I personally have no objection to quizzing presidential candidates about their faith. The problem lies more with the voters than with the politicians, who, after all, merely parrot back to us what they think we want to hear. So if we ask candidates about their faith, let’s first of all listen to the answers. More important, let’s interrogate those claims.

Suppose, for example, that when George W. Bush declared that Jesus was his favorite philosopher on the eve of the 2000 Iowa precinct caucuses, someone had asked: “Governor Bush, Jesus, your favorite philosopher, calls on his followers to be peacemakers, to love their enemies, and to turn the other cheek. How will that affect your foreign policy, especially in the event of, say, an attack on the United States?”

Or: “Governor Bush, Jesus expressed concerned for the tiniest sparrow. Will that sentiment find any resonance in your environmental policies?”

I suspect that if we, the voters, began seriously to interrogate the faith claims and the religious rhetoric of our politicians, one of two things would happen. Either they would seek to live up to those claims — as no president over the last half century other than Jimmy Carter has done — or they would cease making empty statements that are utterly devoid of content.

Jonathan L Mandell

Dear Reader,

In The Fray is a nonprofit staffed by volunteers. If you liked this piece, could you

please donate $10? If you want to help, you can also:

Activist Lupe Anguiano reflects on a life spent fighting for equality.

Activist Lupe Anguiano reflects on a life spent fighting for equality.

A conversation with Raphael Cohen-Almagor on the prospects for Israeli peace.

A conversation with Raphael Cohen-Almagor on the prospects for Israeli peace.