“I didn’t have any big achievements or contributions in my life,” my grandfather said to me, “but I painstakingly worked, and as an average member of the working class, I’m still very capable.”

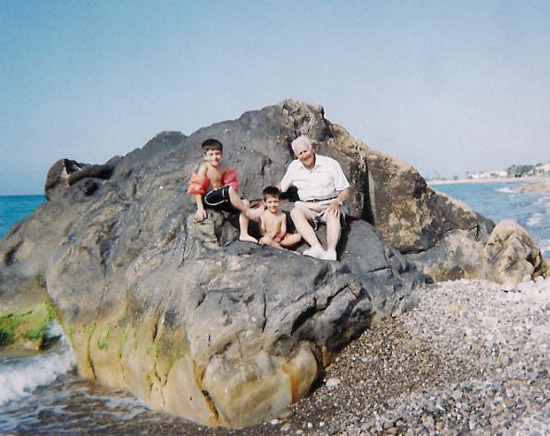

My grandfather is known for his practicality and plain-spokenness, but not for his sentimentality. Driving with him and my grandmother on a trip to their childhood village of Xiqi, his sudden sincerity caught me off guard. As we wound our way through Anxi County’s numerous mountains, I realized the magnificent vistas of peaks girdled by tea terraces and sleepy hamlets was triggering something inside him.

“I worked on this road that year when I wasn’t accepted to any universities,” my grandfather said. “This is it. Right here. Your grandmother and I both worked on it.”

Although the location was the same, the paved, narrow, serpentine road was a far cry from the original trail my grandparents helped build 54 years ago. Burdened with his landlord class background, my grandfather suffered persecution from the village peasants who forced him to build the road, carrying bricks that were too heavy for him. Having graduated from Anxi High School, my grandfather’s background also led to his rejection from every university to which he applied. That year, he had no choice but to toil in the fields. Understandably, he doesn’t have many kind words to say about Mao Zedong.

“Some people said that back then, if Mao farted and proclaimed his fart smelled good, you couldn’t say he was wrong. If you did, you were a counter-revolutionary.”

In the car, my grandmother grumbled, “Why are you saying all this?”

“There’s freedom of speech now,” he snapped back. “Americans can criticize even their president. Stop pretending like we live in a Marxist-Leninist society.”

Xiqi’s villagers have stopped pretending. Maoist sayings painted on the walls of houses to demonstrate one’s revolutionary fervor had faded nearly beyond recognition. The once bright red ink had weathered away or perhaps had been scrubbed off by disillusioned peasants. One saying stated “Everyone must bear responsibility for counter-revolutionaries,” while another stated “Everyone engages in production, every household ensures security.” These slogans, forged during the Cultural Revolution and condemning capitalist roaders, have been replaced by Haier and China Mobile advertisements.

Xiqi has always been a starting point and never a destination. The countryside was where you stayed if you didn’t have what it took to make your way out to the cities. When my grandmother’s oldest brother broke through to higher education, villagers slaughtered pigs, carried him on a litter, and performed songs for three days. Xiqi’s people have always looked outward, trying to escape from the impoverished valley in which they were born. Those that succeeded have paid respect to their forbears by visiting and donating money to the village.

Xiqi’s surrounding mountains, which villagers said resembled a prone tiger, were once stripped bare of their trees by peasants desperate for firewood because they were unable to afford gas or coal. Today, saplings once again clothe the tiger, but now row after row of tea terraces are also carved into its flanks. Before Deng Xiaoping’s economic reforms, Xiqi peasants relied on subsistence farming to scrape out a meager living; now they’ve devoted acres of farmland to growing tea as a cash crop.

There were probably, at most, a couple hundred people in the village when I visited, all of them engaged in some part of the tea production process. Many dwellings were abandoned, and rivers that once accommodated sampans were now trickles of water. Most of the males were away selling enormous cloth bags filled with tea leaves in a nearby town, while the women, donning straw hats and crouching in the soil beneath a fierce noonday sun, picked tea in the fields. The very elderly and the very young walked around amidst mongrel dogs and flocks of chicken and geese; adolescents and young adults were nowhere to be seen.

But according to my grandparents, compared to the rest of rural China, Xiqi’s peasants have done very well for themselves. Funded by revenue generated from hundreds of acres of tea shrubs and donations from wealthy, overseas family members, Xiqi farmers have built better homes, temples, and village infrastructure —all signs of their rising standard of living.

Expensive, four-story houses fitted with shiny, ceramic roof tiles and enclosed by metal gates have sprung up next to dilapidated hovels. Many families had moved into their new residences and placed their ancestors’ spirit tablets in their old rammed earth homes.

Some ancestors are better off. Pooling together their money, family members have constructed many new kinship clan shrines. A new temple built in 2007 for the Taoist god Xuan Wu cost over a quarter of a million dollars (USD). Intricate dragon statues and stone carvings decorate the temple’s interior, while power lines, water pipes, and paved roads can be seen crisscrossing through the village from the temple’s threshold.

My grandparents left their village thinking they would never return. Rural life was grueling, and there was nothing in Xiqi for them except political discrimination, poverty, and hunger. Yet here they were again, showing me the mud houses where they were born, the room where they learned to play the lute with their cousins, and the elementary school where they first met while teaching night classes to illiterate peasants.

“I walked out of my hometown by going to college,” my grandfather reminisced about the second time he applied and made it in. “If it weren’t for college, I’d be just like the village peasants right now. I’d be stuck there. My face toward the loess, my back toward the sky.”

Determined to escape from their rural upbringing, my grandparents confronted larger-than-life forces of revolution, calamitous famine, and massive socioeconomic upheavals. My grandmother left her family at the age of 16 from Xiqi to seek work in the city, while my grandfather chose the unpopular college specialization of geological surveys just to have a chance at leaving the village. Later, his job of searching for ore took him on far-flung journeys through at least two-thirds of China.

Although my grandparents grew up in a rural environment, they say they could never become used to living in Xiqi again. Despite the rising living standards brought by Deng’s economic reforms, the village has remained the same at heart. Many of the customs and folklore that existed 39 generations ago survive to this very day despite wave after wave of social engineering projects fixed on the eradication of the village’s traditions. Spirit tablets burned in the fires of the Cultural Revolution were remade. An effigy of Xuan Wu about to be shattered in the “Smash the Four Olds campaign was secretly saved. Peasants still live their lives in ways similar to past generations.

On our way back from Xiqi, my grandparents said that if I hadn’t asked to see their old village, they wouldn’t have gone on their own. Although much is still the same, from their perspective, the place and its people have changed. The layout of the village looks eerily unfamiliar. Close family and friends have either moved out or passed away. What used to be home no longer feels like a place they know, and they don’t plan on visiting much in the future.

“We have no more close relatives left there,” my grandmother said. “We’ve done all that we ought to do.”

My grandparents visited their parents when they were alive, swept their tombs when they passed away, lit joss sticks, burned spirit money, and donated money for family shrines and Xuan Wu’s temple. They feel they’ve fulfilled their filial duties, and they want to move on.

“Do you remember? When Grandmother was still alive, Mom frequently went back,” my own mother told my uncle afterward. “Ever since our grandmother passed away, Mom doesn’t feel like that place is home anymore.” In many ways, it is my grandparents who have changed, not the village.

I tend to romanticize the past and harbor nostalgic feelings for bygone eras to create a safe haven where I can seek shelter from the present. As a reminder of my own uncertain life trajectory, the here and now often feels doubtful and, at times, frightening. This is the same fear my grandfather felt while laboring away on the village road the year every university turned him down. It is the same fear my grandmother felt when she left home at the age of 16 to seek work in a city 280 miles away. By looking back on their accomplishments in the face of overwhelming odds, their fear has evolved into pride, but mine is just beginning. Xiqi was a chance for me to see their humble conditions and remind myself that my family has produced individuals who will never be passive, but who will instead constantly struggle and strive for the best.

So this is not a story of how I returned to my ancestral home, felt rooted, found meaning, and found myself. I’m not sure that would be a very interesting story. As much as I wanted to feel a sense of belonging to the village where my ancestors have lived — generation after generation, for nearly eight centuries — Xiqi felt foreign and its lifestyle incompatible. My immediate family has gone a long way in three short generations. My grandparents’ native tongue is Min Nan; my mother’s is Mandarin; and mine is English. My grandparents believe in Taoism and Buddhism; my mother has been baptized; and I’m still confused and undecided. The drastic changes Xiqi and my family have undergone remind me that the pace of today’s world is only increasing, and even things I once imagined to be everlasting can change.

But I still listen rapt with attention when my grandparents tell stories about how they beat pots and pans during Mao’s Kill a Sparrow campaign until sparrows fell out of the sky from utter exhaustion, or about how the water monkey, a mythical underwater creature that dragged village children to a watery grave, was vanquished. By writing down their stories and memories, I pay tribute to ancestors and my grandparents in my own way.

- Follow us on Twitter: @inthefray

- Comment on stories or like us on Facebook

- Subscribe to our free email newsletter

- Send us your writing, photography, or artwork

- Republish our Creative Commons-licensed content