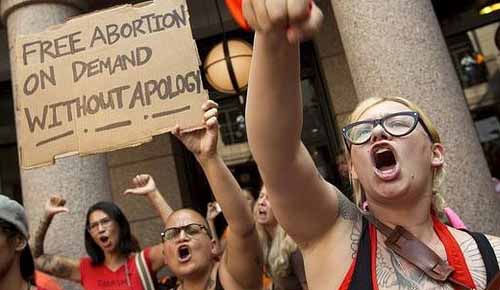

The first job I got out of college was at a health center that performs abortions in Atlanta. This was just after September 11, when abortion clinics across the country were receiving threatening notes in envelopes containing a white powder that the senders claimed (it turned out, falsely) was anthrax. The health center where I worked received one of these letters. For the first time, I had to grapple with the fact that the work I was doing put me in danger. I made the choice to put principle over fear and have been an outspoken advocate of abortion rights ever since.

For a long time, I toed the line on abortion. I had little patience for people who identified as pro-life, especially when they were members of my own family. Holiday dinners were ruined when I stormed self-righteously from the table after arguing with my sister. I cared more about getting my politics across than getting along with the people I loved.

As I learned to value community more than ideology, I became less certain that dogmatism creates a better world. Now, I no longer use abortion as a litmus test for determining whether someone’s perspective is “right” or “wrong.” To me, abortion is a health-care necessity, it is a human right, and sometimes, it is a heartbreaking tragedy.

Yet the national abortion debate continues, polarizing Americans more than perhaps any other political issue. Democratic state senator Wendy Davis was catapulted to instant celebrity last month as a result of her thirteen-hour filibuster of a proposed law to heavily restrict abortion access in Texas. In the end, the bill was voted on and passed, and the filibuster served little purpose beyond spectacle for reproductive health advocates, clinic workers, and the people they both serve.

It is lamentable that America — and, to some degree, the world — keeps having the same fruitlessly hyperbolic scrabbles over abortion that rarely effect meaningful change, much less bring about greater understanding across the issue’s battle lines. But there are some who seek to change the conversation.

In last month’s New York Times, medical student Joshua Lang wrote about what happens to women who are denied abortions. Lang provided a nuanced view of recent research on the outcomes these women, and their children, experience. He coupled this analysis with an affecting story that shows the complex reality of unexpected — and unwanted — motherhood.

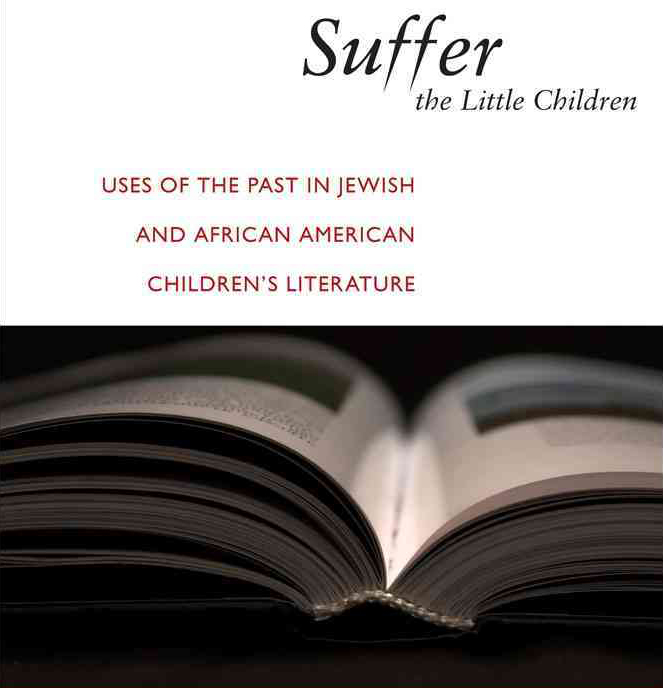

Sarah Erdreich’s new book, Generation Roe: Inside the Future of the Pro-Choice Movement, takes a similarly balanced approach. (The essay currently featured on our site, Looking Back on an Abortion, is an excerpt from Erdreich’s book.) Drawing from her interviews with women who have had abortions, Erdreich highlights views often left out of the intensely partisan debate. She points out that many women and men want to move beyond the stale and divisive rhetoric about the sanctity of life or a woman’s right to choose.

These ideas are not new, but they are gaining traction. Perhaps this is evidence that someday we will finally be able to call a truce in this bitter culture war.

Read an excerpt from Sarah Erdreich’s Generation Roe.

Correction, July 15, 2013: Due to an editing error, Sarah Erdreich’s name was misspelled in one reference.

Mandy Van Deven Mandy Van Deven was previously In The Fray’s managing editor. Site: mandyvandeven.com | Twitter: @mandyvandeven

- Follow us on Twitter: @inthefray

- Comment on stories or like us on Facebook

- Subscribe to our free email newsletter

- Send us your writing, photography, or artwork

- Republish our Creative Commons-licensed content