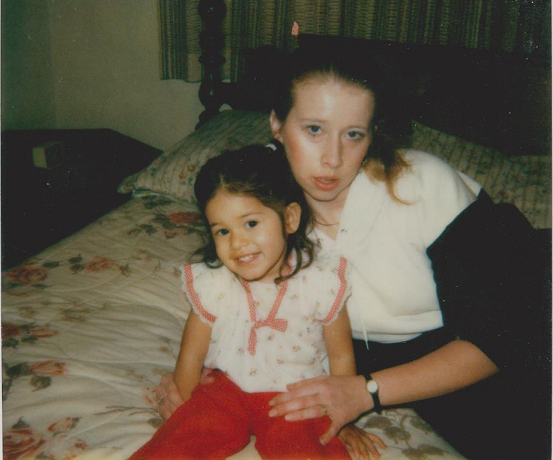

At the height of my teenage apathy, my mom made me squeal with delight by smuggling a kitten into our home in a cardboard box she’d found at work. She burst into my bedroom excitedly and shoved the box toward me. When I saw its tiny, grey nose and bright, yellow eyes, I fell in love just like my mom.

My dad, however, had a strict “no pets” policy. Caring for a cat would cost too much money, he said. He and my mom already struggled to afford food. For days, my parents fought over the kitten while I held out hope I could have this one little, good thing in a house that all too often felt devoid of good things.

My dad, however, had a strict “no pets” policy. Caring for a cat would cost too much money, he said. He and my mom already struggled to afford food. For days, my parents fought over the kitten while I held out hope I could have this one little, good thing in a house that all too often felt devoid of good things.

Shockingly, my mom won the fight. I was given the task of naming the kitten. I chose “Cindy,” sort of as a joke to make my best friend Cindy laugh. That was the cat’s name until a year later when she gave birth to a litter of kittens in a cupboard in my parents’ house. We kept one of the kittens, Jacky, and gave the rest away. Overnight, Cindy became “Mama.”

When I talk with friends who aren’t “animal people,” it’s difficult to articulate just how big a part of your family a pet becomes. For thirteen years, I knew I could walk into my parents’ living room — no matter how unpleasant that experience could sometimes be — and there Mama would be. She would sit on my lap, rub her face against mine, and purr. If I spoke to her, she’d meow in response to everything I said.

Mama helped my mom to cope, too, during some hard times. Ten years ago, my mom was laid off. She had worked for over two decades as a janitor at a hospital. It was the only job she’d ever known.

After she was let go, my mom’s world became very small. Once a woman who had refused to leave the house without a face full of makeup, long nails painted bright red, and a cloud of perfume around her, my mom stopped caring about her appearance. She stopped leaving the house. She stopped talking. She stopped getting dressed. Her life stopped.

I thought she was horribly depressed — and I’m sure that was part of it, but physically, she was also broken. I made doctor’s appointments for her and refilled her prescriptions. I wrote her doctors pretending to be her, hoping they could tell me what exactly was ailing her. It all fell flat. She’d spend her days sitting on the edge of her bed, watching TV and chain-smoking, seemingly unconcerned about the state of her life.

Mama, who was without a doubt my mom’s cat, sat beside her. Or on top of her. Or somewhere on the bed with her. She was always near.

Three years ago, my mom died. The night before, I cried for hours, knowing in my gut that something was very wrong. I called my older brother and told him I needed help. I didn’t know what to do, I said. I was panicking, and we were losing our mom.

My brother was wrapped up in his own life, battling an addiction I wouldn’t be aware of until later. He offered me no advice and little comfort. Afterward, I sat on my bed and cried even more. Mama sat by my side, rubbing her face against me and intermittently meowing.

When my mom died later that night, she was alone. Not even Mama was in the room with her. The only indication my mom ever existed was in the few things she left behind: a hairbrush, some expired makeup, pajamas, and her cat.

The rest of my family couldn’t pull it together after my mom’s unexpected death. My two brothers left their children in my care in order to go out drinking into the early morning hours. It was even worse when they stayed home and drank themselves into a stupor, crying unabashedly about how my parents didn’t love them enough. My dad sat on the couch, frozen.

As for me, I’ve never felt safe letting myself be vulnerable in front of my family. When you grow up in a house where basic needs — such as knowing you’re loved — go unmet, you learn to make it appear as if you don’t have needs. To do otherwise is setting yourself up for disappointment.

In other words, falling apart after my mom’s death wasn’t an option for me. Instead, I hustled to pay for the funeral, shamelessly hitting up my editors for advances and scouring Craigslist for affordable plots. I sat through excruciating sessions with a Catholic priest who scolded my family for not being Catholic enough — while happily taking $300 to appear at my mother’s funeral. I cared for my nieces and cooked for all of the family that had suddenly come out of the woodwork, showing up at our house bearing sympathy and expecting a meal in return.

I didn’t cry in front of anyone, ever.

I would lose it when no one was around. No one, that is, except Mama. She always seemed to be there. When I howled in pain on the floor, she would look panic-stricken. When I got up and composed myself, she’d settle on my lap, purring.

Animals are so powerful in their love and kindness. Very few people have provided me with the kind of comfort Mama did after my mom’s death.

Eventually, Mama became a free agent, loving everyone and belonging to no one. After a few months, she settled on my great-uncle Willie, then seventy-nine years old, who had been homeless before my mom invited him to live with our family. Fast friends, they soon spent every moment together.

I, of course, had Jacky, Mama’s baby. He’d stuck with me through bad relationships, family blowups, and even a move to the Arizona desert that made us both miserable. He consoled me as I was grieving.

Three years after my mom died, Mama became seriously ill. Last October, I went out of town for two weeks. When I returned, Mama had dwindled away to skin and bones. I had the same gut feeling about her that I’d had about my mom. When I saw the vet the following week, I was blunt: “You need to tell me what I already know.”

It was cancer. The vet gave her a few weeks to live.

I knew it would be rough, but what I didn’t expect was how much my experience caring for Mama would mirror the final months of my mom’s life. In the weeks leading up to her death, my mom had often asked me to sit in bed with her. At the time, I felt that being in such close proximity to my fading, ill mother was too overwhelming. After a few minutes I would come up with an excuse and leave the room. In retrospect, I deeply regret not spending that time with her. It wasn’t really her illness that frightened me; it was my need for her. I needed my mom to return to who she was, to become my mom again — not this sick, depressed person I didn’t even know how to sit next to.

I wanted Mama to feel loved and comforted by my presence, but I couldn’t shake that same selfish need for her to return to normal, to fatten up and follow me around, meowing. I knew it wasn’t a possibility and never would be again, and that sense of loss made me hesitate, just as it had with my mom.

Late at night, when no one was around, I held Mama, crying as I traced her brittle bones with my fingertips. When I spoke to her, she looked up at me, but could no longer respond the way she used to. Her mouth would open, but no sound would come out.

Soon, Mama could barely walk. She ate voraciously, but it was never enough. She rarely moved. She lay on a pile of blankets on the coffee table, a place she was never allowed before. For whatever reason, it was the only place she wanted to be — and so we let her be.

We scheduled her to be put to sleep on December 14. That day, in a rare display of energy, Mama pulled herself up, jumped/fell off the coffee table, and stumbled to the front door. When she was well, she would stand in that same spot meowing, demanding to be let out into the front yard, where she would stretch herself out and slow-blink in the sunshine. I picked her up, and together we lay down on the lawn. She rubbed her face into the grass. The last few days in Los Angeles it had been forty degrees. That day, it was seventy-five, and Mama soaked it up. I sat there in pain, knowing what she didn’t.

One of the saddest things I’ve ever seen in my life is my dad and my uncle Willie crying over Mama, running their hands over her bony back, telling her they loved her just moments before the vet gave her the injection. I had to leave the room. I couldn’t bear to see the men in my life so fragile, couldn’t stand to see Mama die right before me. I walked out of the room without saying a word, walked through the hallway and out past the waiting room, smiling at the receptionist as I passed, only to turn a corner outside the building and burst into tears.

When I got home, I crawled into bed and held Mama’s collar close. I traced its edges with my fingertips, thinking about how little of the physical world we really leave behind. Soon, Jacky jumped into bed with me, purring into my neck. As I drifted off to sleep I thought about how we’d both lost our mothers and how we would find comfort in each other.

Tina Vasquez

Dear Reader,

In The Fray is a nonprofit staffed by volunteers. If you liked this piece, could you

please donate $10? If you want to help, you can also: