A police officer wearing protective gear and holding an automatic machine gun stands in the middle of First Avenue. An armed motorcade rolls by him and into the parking lot he’s guarding. A dozen people with cameras wait at the top of the stairs that provide access from my street to the avenue below.

It’s a Wednesday in September, and I’m headed to the pharmacy.

Where I live

I share a block, which includes three fire hydrants, twenty street parking spaces, and a mail carrier named Bill, with the Perutusan Tetap Malaysia Ke Pertubuhan Bangsa-Bangsa Bersatu, or Permanent Mission of Malaysia to the United Nations.

Bill is frustrated that the recent shakeup at the Postal Service has left him with an unbalanced route — all his buildings are residential except one, the Malaysian Mission, simply because it’s on the north side of the block, and that’s where he rolls his mail cart. He tells me, almost every day, that he’d rather cross the street to serve another residential building than stay on the same side to serve a commercial one.

I often see VIP guests arrive at the Malaysian Mission. They step from black Lincolns and gather on the sidewalk in tight bouquets of hand-painted sarongs. Well-behaved children attach themselves to thin wrists. The groups disappear into the sleek high-rise while the Lincolns idle, their drivers dozing in the cool air furnished by the running engines.

My neighbor Joanne idles, too, at her first-floor window, until the dignitaries and their families are inside. Then she peels out, knocks on windows, and shouts at the drivers to move along: “No parking! Don’t you see the signs?” Every evening, Joanne tirelessly writes letters to the NYC Taxi and Limousine Commission and calls 311 with plate numbers. She logs the offenses of the drivers — toxic exhaust, valuable loading and unloading spots taken, candy bar wrappers on the street, plastic bottles filled with urine tossed in the gutter — and reports them to our local community board services agency. As to the last of the offenses — the bottles — I’ve never seen one. Perhaps I’m distracted by the gold thread in the sarongs, burning in the late afternoon sun as it reflects indiscriminately off each west-facing window of the United Nations headquarters.

What happens inside that building has always been, and will likely always be, a mystery to me. As for community appeal, I like the glistening exterior, the row of flagpoles, and the general vibe of importance. (Once, a motorcade bearing then-Secretary-General Kofi Annan passed by me, and I turned downright giddy.) I like the banners outside my building that welcome visitors to “UN Way.” Alongside “No Parking 8-6” signs are flags from Uzbekistan, Peru, Costa Rica, Kiribati, and other countries.

This is Tudor City, an eighty-year-old neighborhood on the eastern edge of Midtown Manhattan. Unlike other New York neighborhoods, Tudor City is just two square blocks, from Forty-First to Forty-Third Streets between Second and First Avenues.

This section of the island of Manhattan gently slopes upward to a granite cliff that once offered unobstructed views of the East River. In the shadow of the cliff, down on First Avenue, slaughterhouses and tenement buildings were erected in the early twentieth century. The architects who designed Tudor City’s gigantic gothic-style apartment houses included only small windows facing east to minimize the stench from below.

In the late 1940s, the slaughterhouses were torn down, and the United Nations Headquarters was built in their place. Though it is sometimes difficult for me to understand why Midtown Manhattan was chosen for the UN Headquarters and not a large open area somewhere with ample parking space, I chalk my lack of understanding up to post-9/11 worries about security. In 1945, New York apparently looked like an ideal — and safe — place to build the United Nations flagship complex. The topography does ensure that a car cannot drive straight to the UN’s front door. And the UN, juxtaposed with the gothic buildings, has Hollywood allure. The spotlights from late-night film shoots transform our neighborhood from night into day.

I moved here right after September 11, 2001. The prices in Midtown, particularly in Tudor City, had dropped substantially in the wake of residents fleeing for the presumed safety of the suburbs. My first impression of the place was that it was a Midtown anomaly, situated so close to Grand Central Station but with two little parks and the feel of a cul-de-sac. I noted snipers on several rooftops.

The annual UN General Assembly

Joanne, naturally, is the one who alerts us every year when the UN General Assembly is coming. Diplomats from over a hundred nations come to meet, greet, and speak. Every issue under the increasingly dangerous sun is discussed: environment, health, war, energy, food, water, genocide.

Out here, it’s like a festival of lights for my neighbors and me — red and blue flashes from police cars, neon protest posters, shiny orange cones. Being part of it by virtue of living in it, however, can be frustrating. The New York City Police Department, feds, and private security staff lock down the area.

The diplomats, however, don’t always stay in the neighborhood. (Qaddafi and his tent are a case in point. This year the Libyan leader, wary of elevators, tried to erect his private canvas sleeping space in Central Park and on Donald Trump’s estate in White Plains. He was denied both times.) Diplomats have needs. They visit friends and go out to dinner. My graduate school adviser, Diane, used to live quite a distance from the UN, on the Upper West Side. Still, she was stopped on West Seventy-Ninth Street: “Next thing I knew I was up against the wall being yelled at. There were tanks or Humvees and men with automatic weapons. I was in shock, but it turned out they were just providing security for Arafat, who’d come to a stationery store on the block to buy a fountain pen.” The footage of President Obama’s visit this year shows him jogging on a city street that has been emptied of cars and people. Diane and I laugh about the great lengths security staff will go to so that heads of state can do “normal” things.

Joanne forwards a notice to our building from Deputy Inspector Ted W. Bernstein, commanding officer of the Seventeenth Precinct. The accompanying map reads like a battle plan: street closures and coned-off lanes, checkpoints and vehicle inspection sites. No parking is allowed, except, it seems, for those indomitable black cars that crawl our block like roaches.

This year there is an added threat of terror. Reports of a plot, allegedly one of the most complex and sophisticated since 9/11, lead the news cycle. Authorities have discovered plans to explode homemade bombs in Grand Central Station and other New York transit hubs. Though the plot seems to have been thwarted, security is heightened, particularly on the subways. But it’s UN Week, and we are encouraged to take the subway rather than cabs or buses. I can’t decide if I’m comforted or disconcerted when Police Commissioner Ray Kelly announces that the city, accustomed to living in a state of high alert, is doing what it always does to remain secure.

A day on the ground

After the pharmacy, I hop on a bus at Nelson and Winnie Mandela Corner (just about everything in this neighborhood is named for a diplomatic star or two) and head toward the west side to pick up my camera from a repair shop. The trip takes twice as long as it usually does, and by the time I’m back, I’m ready for an afternoon latté. While waiting in line at Starbucks, I watch a bus pull up to the curb and empty itself of men in black, green, and red T-shirts. They unfurl flags and straighten out signs.

By the time I have my coffee, the men have turned up Second Avenue, along the stretch that has been renamed Yitzhak Rabin Way, and I follow them on my way to Alpian’s Dry Cleaners to drop off some clothes. I hear the noise from Dag Hammarskjöld Plaza, on Forty-Sixth, well before I arrive.

“United Nations, we need your help, right now, right now,” a group from Tibet chants. I can’t cross Forty-Sixth Street at Second to continue on to the dry cleaners on Forty-Eighth because of the throngs of people and police barricades on both sides of the street. I can’t cross to the other side of the avenue either because a crowd of people has gathered as far as I can see up Forty-Sixth. While I debate what to do, a man selling buttons that read “Obama Rocks” and “Green Up Iran” proudly announces to no one in particular that he has only two of his thirty-six “America: A Nation of Immigrants” buttons left.

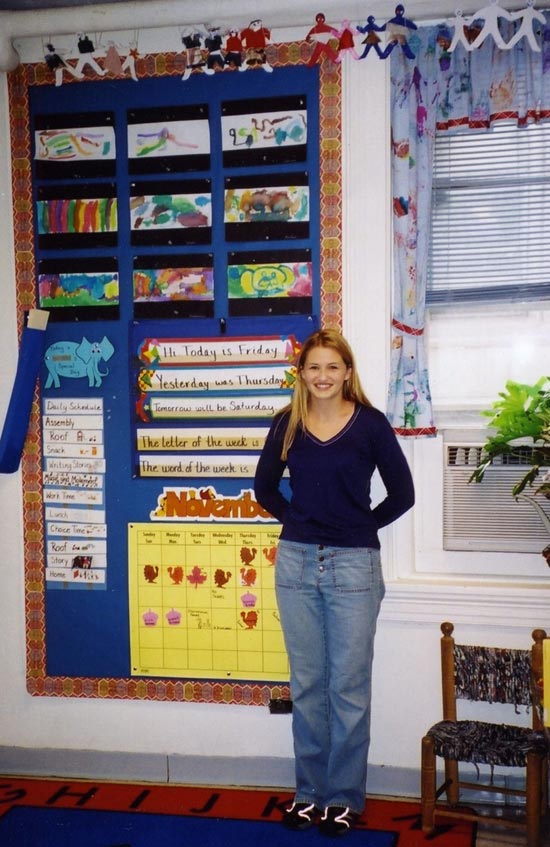

I reason that if I walk with the flow of foot traffic and not against it, I will be able to turn left on First Avenue and continue on my way. Halfway down the block I find an opening between barriers and sneak into the center of the street where it’s a little less crowded. I walk alongside several people with cameras and a woman with a megaphone. We pass the Holy Family Church, where parents are waiting for their children to get out of school.

Suddenly, the woman yells into her megaphone, “Hey hey, ho ho, Ahmadinejad has to go.” I look around. The crowd has organized into a march behind a banner as wide as the street. In front of us, cops pull barriers from the side of the street to erect a blockade. I follow some quick thinkers through an opening before it closes up. Behind the barriers, those ahead of the pack, some tourists and some journalists, are stuck. The cops won’t let them out. Protesters are still moving forward, repeating the woman’s spirited calls.

I’ve never been part of a protest. My vast experience as a couch observer of the news, however, makes me concerned that the protesters might push up against the barriers and strain to break through, try to overtake the UN, possibly Ahmadinejad himself. I wonder if the police will act especially brutally, if some child who has just come out of the Holy Family School will be accidentally crushed. Last year while I was in Argentina for a wedding, farmers there protesting the government blocked the roads with their equipment, causing such backups the bride’s ninety-year-old grandmother sat in a bus for eighteen hours when it should have been a two-hour trip.

Nothing that dramatic happens, of course. The police officers wait patiently on the other side of the barriers, chatting. Onlookers snap pictures. And the protesters stop exactly where they are told to stop. In a display of what I see as great restraint, power, and organization, they speak their collective mind, in unison, repeating the same simple statement. Hey hey. Ho ho. Ahmadinejad has to go. It moves me with its immobility. The voices alone, though loud, must sound like music three blocks south at the UN Headquarters.

On either side of the Iranian march are groups from Taiwan, Cameroon, Tibet, Sri Lanka, and Israel squeezed in together. An older man with a long, grey, scraggly braid yells at the protesters, “It’s a society of wimps! You’re wasting your time, you assholes!” Remarkably, a group sits on the ground in the center, unfazed, eyes closed in meditation or prayer. Behind them, a sign reads, “Falun Dafa is Great.”

The chaos of so many nations with conflicting wants is muted by the general human need of expression and order, mail delivery and lunch, money and prayer. It’s almost as if there are too many sides to make for conflict during the Assembly, or that conflict itself is what makes the Assembly operate smoothly. No matter what is going on behind those reflective windows, out here there is some sort of peace.

My arms are tired from balancing my coffee and purse with my camera bag and the clothes for dry cleaning, though I’m grateful for the camera, as I too become an onlooker taking pictures. Finally, I make it up First Avenue to Alpian’s. On the way home, I stop in Amreen’s Hallmark to buy a birthday card for my niece. I ask Amreen’s daughter, who works the register, how it’s gone so far.

“Good. Not too busy,” she says as she rings up the $3 card.

“Have you had more customers than usual?”

She shrugs. “No, but we have sold out of some stuff.” She points toward a shelf. “We’ve sold a bunch of our New York trinkets!”

As I approach my building, a motorcade stops right in front. Suited men get out and flank a town car. Behind it, a suburban full of men in vests holding machine guns waits. I’m about five feet from them. My building’s awning is behind me, and a group of tourists is watching. A woman walking her dog approaches. The shih tzu makes his big decision of the afternoon — curb or tree — and chooses the curb. The dog squats, the woman watches with plastic bag ready, I snap a photo of the men with guns, the suited men on the street wait for a signal then return to their vehicles, and the motorcade rolls away.

Inside I ask José at the front desk how the day has been. “Beautiful!” he says. It’s a beautiful day in the neighborhood. A neighbor writes on her Facebook wall, “I walked outside to protests by every ethnic and religious group known to humanity. Then, President Obama passed by in a car, waving. I almost got picked up by secret service, and [literally] bumped into Katie Couric. The traffic is only a small price to pay for this much fun!” In true UN General Assembly style, we get a little bit of the spotlight — and the festival of lights — every year.

Joanne, however, is already on to other things. I get an email about bus route interruptions as construction on a new Second Avenue subway line proceeds. And as for my friend on Facebook, she soon follows her comment with another: “On second thought, I’m so over the important people hanging out in my hood. They are clearly diluting my status as a local celeb.”

- Follow us on Twitter: @inthefray

- Comment on stories or like us on Facebook

- Subscribe to our free email newsletter

- Send us your writing, photography, or artwork

- Republish our Creative Commons-licensed content