Catholics and Communists have committed great crimes, but at least they have not stood aside, like an established society, and been indifferent … If you have abandoned one faith, do not abandon all faith. There is always an alternative to the faith we lose. Or is it the same faith under another mask? —Graham Greene, The Comedians

A couple of hours across the border from Haiti, in the hot sprawling sugar plantations of the Dominican Republic, lives a man everyone in the area knows. When the locals see his truck dragging a bridal train of dust along the unpaved plantation roads, they stop what they are doing and come forward. Yes, they all know him, the Haitian migrants, Dominicans of Haitian descent, and Dominicans who live on this plantation near the seaside mining town of Baraona. They have all have exchanged a genial word with him and shaken his hand.

His real name is Pierre Ruquoy, though few of the locals use it. It has been almost three decades since the Belgian priest arrived during the corrupt Balauger regime, when there was little electricity outside the capital, and the roads were so terrible it took eight hours to make a trip that now requires only two.

Back in 1975, Pedro rode his mule up into the mountains to do battle with the windmills of poverty and suffering, or as he puts it, to learn with “the people.” Since then, little has changed. The electricity still fails regularly, most of the roads remain unpaved, and corruption persists.

But one can say this, at least: for many years now, the people have had a hand to shake.

Now 52, Pedro lives in a modest house paid for by the Church on the edge of Batey 5. His parish is the batey itself, the warren of shacks that lodges los braceros, the cane cutters. With its dry earth and utilitarian name, its checkpoints and barbed wire, Batey 5 looks and sounds like nothing so much as an army base. The checkpoints ensure that workers stay put and prevent rival plantations from stealing each other’s workers. The barbed wire on the shacks is less explicable, because there is almost nothing for a thief to steal, except the occasional rooster tethered to a heavy stone.

While the rest of the Dominican Republic modernizes, little changes on the bateyes. The last few presidential administrations have replaced many of the stick-and-mud shacks with more modern cinderblock lodgings, plastering them with campaign posters afterwards. With the election coming in May, the candidates want visitors to know who has built the cane cutters’ houses.

But for the Haitian cane cutters, the election is a less urgent issue at the moment than the political events happening across the border in their homeland, where in the past few months there has been unrest, a coup, and still more unrest.

When Pedro comes around, he gives the workers news, trying to dispel the rumors that spread like wildfire through the isolated community. As programming director of Radio Enriquillo, a local Catholic radio station, he helps provide news, religious programming, and political advocacy for the braceros. Though Pedro is uncertain how much political power the station actually has, he insists on the value of the listening ear, the proffered hand. To voice the batey’s problems is itself a kind of relief, he says, even if few outside the plantation hear his protest.

All week long, Pedro listens to the confessions of “the people”: a man whose wife has been stolen by a plantation security guard, a young man who wants to avoid marrying the girl he has impregnated, a man whose shoulder is infected and needs antibiotics. But the braceros’ present trouble, says Pedro, is boredom. Now, mid-March, is el tiempo muerto, the dead time between harvests, and they sit around in the shade of their barracks like bored soldiers. Many lie around sick with malaria or rougeole, the measles. The women sit in plastic chairs and watch the laundry dry, and the men take turns trimming each other’s hair. Their children wander around sucking on bits of cane or plastic bags of yellow homemade ice cream. One clever boy ties a rope to another’s bicycle, and they take turns towing each other around through the gray dust that surrounds the gray-green sea of cane stalks.

Many of the workers here are Haitian economic refugees with families to support back home. But the labor that provides the sugar that rots American teeth barely sustains the workers themselves. They usually plan to go to the Dominican Republic and return after the harvest with their wages, but many never leave. To get to the Dominican plantations, they must pay their traffickers 600 Haitian dollars (around $70 U.S.) to take them across the border, a huge sum considering that they earn only $3 a day for cutting cane from 5 a.m. to 5 p.m. And because of interest owed to the traffickers, the immigrants often do not earn enough to make the return trip, and thus remain stuck in the limbo between sustenance and profit.

The Dominican-born braceros with Haitian roots have a related problem, Pedro says. The majority are second-generation Haitians or Dominican-Haitians, fully half of whom do not speak the Haitian language, Kreyol. But according to the Batey Relief Alliance, a group that fights to improve the conditions of the braceros, a third of the workers lack documentation and suffer systematic deportations. In 1997, the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights reported that 25,000 Haitians were sent home in the months of January and February alone, or one out of every eight of the 200,000 workers on the bateyes.

That another stream of Haitians continuously replaces the deported testifies to Haiti’s dire economic conditions. Critics of the deportation policy say the Dominican government’s real agenda is to keep the community in a state of political disorganization. If so, the policy is a success. Often newly-arrived sugar braceros knock at the door of Pedro’s house on the edge of Batey 5, showing up naked, in the middle of the night, after selling their clothes to the traffickers. They have malaria, they have the mumps, they are often heartbroken and tired. Pedro gives them something to wear, something to eat, a place to stay, medicine. But their biggest problem, the lack of respect many Dominicans have for the braceros, is something he, as a foreigner, cannot solve.

“To work here you have to know you are a stranger,” Pedro says, as he drives to the shanties where the braceros live. With a fencer’s lean frame, a gray European moustache, wire-rim glasses, and pants hitched high over his waist, he holds his Nacional cigarette with an intellectual delicacy. “You will never be Dominican,” he says.

By ‘you’ he means himself, but he says it is also the problem of the Haitian immigrants themselves. “It’s important to have confidence in your own identity – then you can bring something and receive something,” Pedro says. “It’s the people who will save the people. There is no people in the world that believes another people will save it.”

These seem odd words coming from a missionary, when one considers the steady flow of aid that comes from the Church. They make more sense when considers that far more aid is needed to close the plantations’ open sewers, to put running water in each house, than the Church can provide.

Pedro can only afford to shelter a dozen or so refugees at his house. Even if the plight of the refugees themselves were eased, he says, refugees would still spill across the border, probably in greater numbers.

Learning about Haiti through sound bites

The economic problems of Haitians in the Dominican Republic are inseparable from the economic problems of Haiti, which are at least partly political in nature, and which never seem to cease. For a few weeks this spring, the world gained an intermittent awareness of those problems, the tides of misery that send Haitians into the sugar cane fields of the Dominican Republic.

One thing is for certain: even if the people could save the people, history has not given them much of a chance. Though the former French colony achieved its independence early – Haiti’s 1804 rebellion was the first successful slave revolt in the history of the Americas – it has endured foreign intervention ever since. In 1915, recognizing Haiti’s strategic proximity to the Windward Passage after the assassination of Haitian President Vilbrun Guillaume Sam, U.S. Marines occupied the country for nearly two decades. After their departure in 1934, the constitution was rewritten, and the infrastructure was improved, but the country remained in a state of economic hardship that undermined the American attempt to create political stability.

“The poorest country in the Western Hemisphere,” we were told in sound bites on the nightly news, as we watched a rebel force creep down from the northern city of Gonaives toward Port-au-Prince. “Forty-five percent of Haitians are illiterate. 70% are unemployed. 30% are malnourished. 80% live in poverty,” the newspapers told us.

These numbers, tragic as they are, were not the story. They were merely the context for the coup that deposed Haitian President Jean-Bertrand Aristide on February 29. It is only natural to wonder, given the nation’s current efforts to bring democracy to Iraq, why the same system was failing yet again just 150 miles from Miami, why there were more dark faces overturning cars and lighting tire barricades afire.

Just as quickly, the rebels reached Port-au-Prince, and the why no longer mattered. Aristide was besieged again, as he had been during a 1991 coup, when he was forced from power by the Haitian Front for Advancement and Progress (FRAPH), a group allied with former dictator Jean-Claude Duvalier. In 1994, out of a sense of moral obligation and a desire to stave off the exodus of Haitian refugees, 20,000 U.S. marines forcibly restored Aristide to power. In February, this cycle repeated itself when our nation heaved a collective sigh of resignation, and dispatched a few thousand Marines, to avoid “a bloodbath”, in U.S. Secretary of State Colin Powell’s formulation.

The question for most of the international community was not whether to intervene – most observers accepted Powell’s analysis – but who to blame for the failure. Aristide’s critics say he strayed too far from his promises. To some he was a tyrant; to others, merely ineffectual. His supporters have another view. They criticize the United Nations and the State Department for pressuring Aristide to accept an economic structural adjustment program in exchange for expediting his return to power – a deal that allegedly made it difficult for Aristide to carry out the reforms he had promised. Some in the Congressional Black Caucus even claim that Washington and Paris engineered his failure as retribution for criticizing their economic policies.

Haitian-American activist Serge Lilavois, 57, is one of those who argues that the reform efforts Aristide proposed never had a chance.

“If you don’t have enough money, you’re going to find people in disagreement with you,” said Lilavois, organizer of the Coalition to Resist the February 29 Coup in Haiti, a New York-based group convinced that Aristide was “coup-d’napped”, when Marines escorted him onto a military plane bound for the Central African Republic. The Coalition says the press exaggerated the human rights abuses of Aristide’s partisans, which they allege numbered only a fraction of those committed by the rebels who deposed him. Lè yo vle touye chen yo di’l fou, goes the Kreyol saying – when they want to kill a dog they say it’s crazy.

Locating divisions

The Coalition has attempted to spread this message, but so far it has not moved beyond the Haitian community, which is itself very divided over the issue. Haitian braceros right across the Dominican border have even less political influence and information than their countrymen in New York City. Indeed, many of the workers of Haitian descent are too poorly educated to recognize pictures of their country’s ousted president when Pedro shows it to them.

In fact, the batey’s ethnic divisions are a more pressing issue for most of the braceros. The plantations are segregated by antihaitianismo, a word that means exactly as it sounds. Haitians suffer tremendous discrimination, even within the economic ghetto of the bateyes. They live apart from the Dominicans and Dominican-Haitians, who are anxious to distinguish themselves from those of even marginally lower social standing, says Pedro.

“Trujillo made the division between Haitians and Dominicans in the batey,” says Pedro, referring to the assassinated former Dominican dictator who, in 1937, attempted to “whiten” the country by slaughtering 30,000 Haitians in a tragedy known as the River Massacre. “Dominican people feel they are Spanish people and it’s a lie. They don’t acknowledge African culture. You have to break the idea that white people are superior.”

The policies of Trujillo, who incidentally was a sugar cane plantation guard as a young man, merely exacerbated an existing hatred, according to Pedro. In fact, the River Massacre took its name from a Spanish slaughter of French pirates on the island during the colonial era; this gives one a sense of the roots of racial hatred that persist on the island of Hispaniola today. It is not surprising that a people whose national identity was defined on these pretenses has suffered from discord ever since, according to Pedro.

An example: for the past couple of months, Pedro has given refuge to a half-dozen young Haitian anti-Aristide student demonstrators, all of them from the upper classes. In January of 2004, they were stopped and detained by Aristide’s militiamen in the Delmas district of Port-au-Prince. They feared for their lives. The government press had taken their picture at the demonstrations they’d helped organize, and read their names on the radio – the primary means of communicating in the mostly illiterate country. The brother of one, Johame, had been a long-time enemy of Aristide’s Lavalas government. Four days earlier, the chimeres had beaten the radio journalist brother of another, Samuel, to the brink of a coma. They worried they would suffer the fate of their friend Brignol Brignol Lindor, a radio station journalist who had been stoned and hacked to death for opposing Aristide’s partisans, the chimeres.

Fortunately, the chimeres did not discover the students’ identities. The students were merely beaten and released, and with the help of Haiti’s Committee of Lawyers for Individual Respect and Liberties (CARLI) (CARLI) they escaped to the Dominican Republic, where they are staying with Pedro. In exchange for shelter, they have agreed to teach a class to the plantation workers, most of whom have had little formal education. Pedro says much of the political instability in Haiti owes to a lack of education among the rural population. It is easy for demagogues to persuade them to unseat governments, he argues.

“There are two countries in Haiti, people who come from Port-au-Prince, and people from the mountains. We try to help them understand what happened in Haiti but it’s not easy. Last week I went to the mountains, and talked to 25 people who had almost made a decision to help [rebel leader] Guy Philippe,” Pedro explains, to demonstrate how poor the flow of information was to the people in the mountains. An interim government had already taken the reigns from Philippe weeks before Pedro’s trip.

Pedro says he wants the class to be an opportunity for the students to learn from the workers. Asked if that was the students’ motive for teaching it, his reply is frustrated.

“They are teaching the class for solidarity with me, he says. “It’s not for the people. They [the workers and the students] speak two different languages.”

Building the New Movement

I am eager to meet the students, nevertheless, wondering if the meeting will provide an example of the people helping the people. I sit with them in the early afternoon at a table under a pavilion in Pedro’s backyard. A refreshing breeze has picked up, and the relaxing click of dominoes fills the hours while Pedro is doing his duty at Radio Enriquillo.

When I ask them how they intend to foster political unity here in the Dominican Republic and across the border, the students evade my questions. Instead, they carry on an intense discussion in French about my presence. Several times I hear the acronym “CIA.” An American’s sudden appearance in the middle of nowhere, the students’ recent experiences, and the long history of clandestine U.S. intervention in Haitian politics make this a reasonable possibility. When I ask the name of their political group, they say they can’t decide, because they are changing it.

“We’re calling it the New Movement,” says Gethro, their unofficial spokesman.

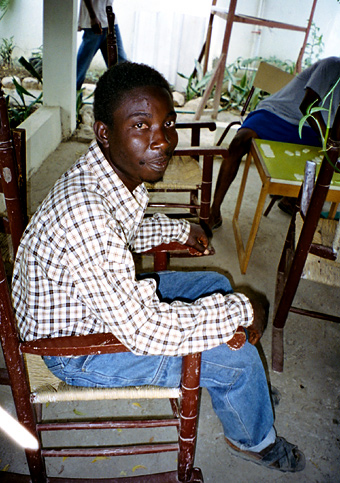

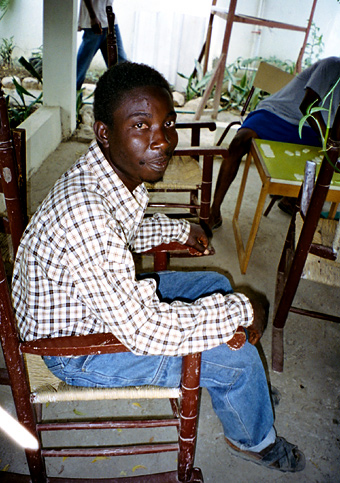

Gethro has the best English, good enough to have qualified him to translate for the U.S. Marines in 1994, the last time they occupied the country. Johame, still in his early 20s, is already graying, and the unspoken leader of the group. Michelle, with short red hair, maintains a petulant silence. Smith is tall and lanky, Samuel a champion cyclist. I cannot resist imagining that I am meeting, in its gawky youth, the future leadership of Haiti, and so I empty out the disorderly contents of my wallet onto the table to calm them.

“Our fathers could be killed,” says Gethro who asks me not to use his and the other students’ surnames. He shows me a local Dominican newspaper printed a few weeks earlier, with a cover story on the political crisis. The photograph shows the students and several of Pedro’s other refugee guests walking together across the batey. The students toss it around angrily.

“It’s the picture,” Gethro explains, stabbing the page with his finger. “It puts us with the other refugees.”

Johame points across the half-finished domino game at Samy (not to be confused with Samuel), a young man who caught malaria while cutting cane, and is now recuperating at Pedro’s house. He speaks no English and looks at us with concern, unsure of what we are saying.

Earlier, Samy said that he came here to look for life but that he hasn’t been able to find it. I wonder if the phrase is as poetic before translation.

“He,” says Johame, referring to his countryman, “is an economic refugee. We are political refugees.”

At first I think the students are upset because the article might endanger their case for political asylum, but Pedro later tells me this is not the case, that indeed, the article, which clearly identifies the students as political refugees, has boosted their chances of qualifying for it.

Their anger, Pedro says, has a much simpler cause: snobbery. This student elite, these brave organizers of the demonstrations against Aristide, have been thrust together by history into the squalor of the batey. Even though their immediate cause, Aristide’s departure, has been achieved, their country remains politically unstable, their university closed. Among the very people they seek to help, and despite their bravery and ideals, they cannot help feeling superior.

Who are the People?

Pedro’s dictum: the people must save the people. If the aid workers and the 2500 foreign peacekeepers sent to Haiti after Aristide’s ouster can only lend a hand, who, then, are the people? Students, braceros, rich mulattoes, political or economic refugees, Haitians or Dominican-Haitians? Who, when the international community returns its attention to more pressing matters, will be left in charge? And whose interest will they have in mind?

Perhaps it is too difficult to predict how things will change for the braceros following the May election in the Dominican Republic. It is harder still to say what will become of Haiti after the election scheduled in 2005. In the meantime, the tiempo muerto continues, and the struggle for survival trumps the political one. Pedro insists that the strength needed for both fights will come from the same source: the people. He takes me to the house of his friend, Noel, one of more than a hundred voodoo priests on the batey. Noel, 76, diabetic and blind, lies naked on a wooden mat in his boxers as we enter. The father of 54 children, he looks younger than he feels.

“He says it is time to die, but I say I don’t agree,” Pedro smiles, after conferring with the other man in Kreyol. Pedro explains he has promised to speak with Baron Cimetiere, the god of the dead, on Noel’s behalf. “I said I have to go to the Pantheon to speak with the spirit of the dead and give rum. Now is not the moment to go to the land of the dead.”

“Can I take a picture of him?” I ask.

Pedro gets the old man’s permission and nods. His son steps inside to close the fly of Noel’s boxers. I take another picture of the priest’s altar, a collection of bottles and dusty picture frames that looks to me like a pile of recycling. Later, as we drive back to Pedro’s house, I ask Pedro what the Church thinks about his close relationship with a heathen religion, and his attendance at voodoo ceremonies.

“It was a problem for them when they saw I visited a voodoo priest,” he says. “The Catholic Church doesn’t accept voodoo as a religion, but the most progressive people in the church call it religiosity. I don’t like to call it religiosity. They tend to say, ‘We have religion, they have religiosity.’ For two centuries voodoo allowed people to maintain their identity – we need to respect it.”

This sounds reasonable, but his tone suggests something greater than respect. I ask him if he believes in voodoo himself.

“Once I was sick and visited the priest. He said, ‘I will see what the spirit can do, but I don’t know what I will say because you are a Catholic priest – anyway, I will say you are a friend.’ He gave me a bottle of water and something else in it, some herbs.”

“Did it work?” I ask, not interested so much in the efficacy of the herbs as in Pedro’s faith in the people, which seems at times greater than his allegiance to the Church.

“Yes,” says Pedro, happily.

I ask him later where he gets his own energy, and he says it has come from the example set by the people he has lived with for more than half his life. “The thing is to live every day,” he answers. “In Europe and in the U.S., we live next month, next week. These people live every day.”

“But,” he adds, after a moment, “that’s a problem too.”

Pedro is strange: a missionary who does not believe he can save people, who accepts the magic of another religion, who has spent his life among a foreign people and yet still considers himself a stranger. If someone so close to the people cannot save it, what does that mean for my country’s efforts, well-intentioned or not, to remake the world in its own image?

We spend the rest of the day driving through the bateyes, Pedro and I. The people come forward to tell him their problems, to share a joke, to shake his hand. I stand beside them quietly, trying to figure out what it is, in that mysterious gesture, that they are really exchanging.

STORY INDEX

MARKETPLACE >

(Order from Powells.com and a portion of each sale goes to InTheFray)

The Comedians by Graham Greene

URL: http://www.powells.com/cgi-bin/partner?partner_id=28164&cgi=product&isbn=0140184945

PUBLICATIONS >

A Creole Language Guide

URL: http://www.geocities.com/frenchcreoles/kreyol/

ORGANIZATIONS >

The Inter-American Commission on Human Rights

URL: http://www.cidh.oas.org/

The Congressional Black Caucus

URL: http://www.house.gov/cummings/cbc/cbchome.htm

Former President Aristide

URL: http://www.afiwi.com/people2.asp?id=21

The Coalition to Resist the February 29 Coup in Haiti

URL: http://www.haiti-progres.com/eng04-21.html

"

Justin Clark

Dear Reader,

In The Fray is a nonprofit staffed by volunteers. If you liked this piece, could you

please donate $10? If you want to help, you can also: