Worshippers kneel on pine needles in front of open Coke bottles and melting candles. Colored ribbons hanging from pointed straw hats cover their faces. Faded wooden saints wearing silk stare from behind glass cases. Clouds of incense muffle the chants of the Tzotzil villagers in San Juan Chamula Chiapas, as busloads of Europeans wear a path in the tile. The tourists outnumber the locals, but they have come to witness the religious ceremonies of indigenous Mexicans.

Who are these “indigenous people” of Latin America, and what does it mean to be an Indian? Few countries in Latin America have tribal registries based on bloodline, and most do not have established reservations. Is the answer in the way people dress, the language they speak, the religion they practice, or the color of their skin? Is it valid to fear that indigenous ways of life are vanishing?

These questions are hard to answer, but need to be explored.

The lines that once separated the “indigenous” from the “Latins” are blurring. Hundreds of years ago, the Spaniards came to key cities of economic and geographic importance. They rarely ventured out of these established areas, allowing indigenous communities to develop in relative isolation. Today, however, cultural isolation is rare. As transportation continues to improve, migration occurs and languages disappear; cultures merge. Now only the extremes are obviously identifiable as “white” or “indigenous.” The majority lie somewhere in the middle.

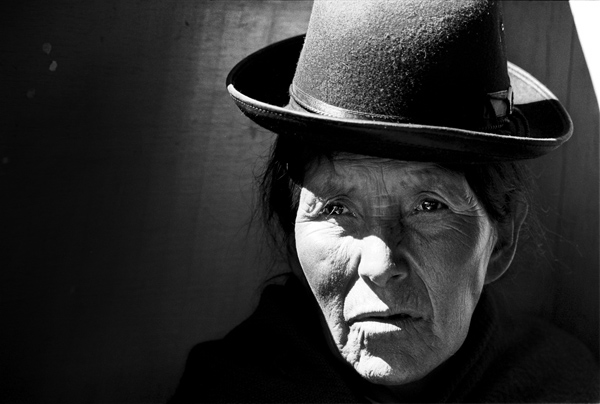

The term “vanishing culture” is frequently used to describe a process that has been occurring for centuries. Cultures are fluid and in a constant state of change. What we now think of as “signs” of the indigenous, such as round, black hats on Aymara women, may not have been recognizable to the same tribes hundreds of years earlier. Many of these “signs” are imports from non-indigenous cultures. I show this cycle of cultural change by photographing isolated indigenous populations, peoples living in mixed cultures, and areas where Indians have become extinct.

For nine years, I photographed in areas of Latin America with large indigenous populations. I worked with Maya in Southern Mexico and Guatemala, Aymara in Bolivia, Quechua in Peru and Ecuador, Tarahumara in Northern Mexico, Guaraní in Argentina and Paraguay, Yagua in the Amazon, and Nivacle in Paraguay, to name just a few. I photographed the vanishing and merging cultures in twelve countries, from the southernmost city in the world in Tierra del Fuego, where the native populations were annihilated, to the Tarahumara cave dwellers of the Copper Canyon on the Mexico-Texas border.

These fifteen images are a small sampling of a larger project. They are documents of street life that show how people live, work, and lead their daily lives. The photographs show the merging of the Indian and Latin cultures and the changing ways of life. They question what it means to be indigenous.

They say there is a city of dolphins at the bottom of the Amazon waters. A lost city. Time passes slowly down there. One day below equals one year above. The pink dolphins of the Amazon don’t have enough mates. So the male dolphins swim to the surface and steal Amazonian women, and the female dolphins steal handsome men. If you stay underwater and live the dolphin life, time appears normal. But when you return to the surface, your village is gone, and a modern city has taken its place. Your family and friends are dead. Eventually, you age as you should and turn to dust as your long-dead ancestors.

They call the pink dolphins “witches”—bad, pink witches.

He gives a hiking tourist directions on how to reach the bottom of the deepest canyon in the world. Then the Tarahumara sits on his bench on the rim of the Copper Canyon and carves a stick and a ball. His shadow points the way.

Like musical notes, the pigs hang in an uneven line. Women inspect and decide on their favorite slabs. A cat hides around the corner, hoping for handouts. A man humming and whittling sticks waits for his wife to shop.

Easter morning on Lake Titicaca. A baby monkey grasps a necklace charm with a fuzzy image of the Virgin of Copacabana. Aymara Indian women in shiny skirts tease children by chasing them down the street with a stuffed frog that has colored stars on its back. Street vendors sell strings of fresh roses for twenty cents and images of the Virgin in barnacle-covered oyster shells. Believers pray for new homes while drunk, chanting priests perch faded plastic houses on their heads.

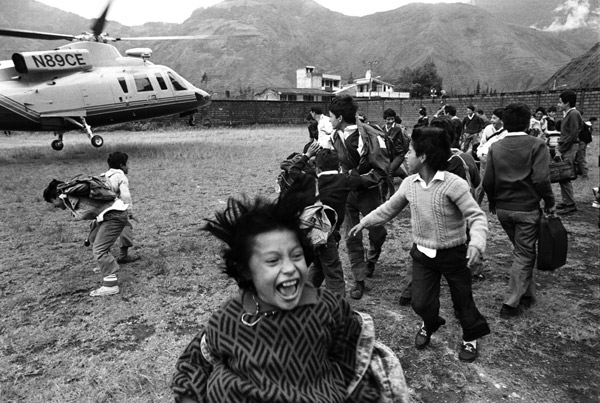

Blades slice thin air and squeeze between mountain peaks. Crowds race down cobbled streets toward the soccer field. Boys spin in circles with arms outstretched and little girls squeal and scream. Parents giggle and sprint ahead of the crowd. The helicopter descends, and the twirling boys push each other closer to the blades. An elegant leg steps out, and a rich visitor comes to town.

Confetti drips like melting snow from hats onto sour shoulders. The day is festive, but they are not. The bride walks out. A guest lifts a hat to sprinkle the woman with more flakes. But nothing touches their faces.

They stare at the sea. Their ancestors came on that sea—slaves—shipwrecked to short freedom and then shuttled to an island off Honduras. These are the Garifuna. They dance with the wind.

View from a damp hotel window. I lift off my blanket as the clouds unveil the town.

Gerónimo carries a pickaxe on his neck and smiles with a chipped tooth. He steps into the mist while his feet break muddy reflections. In the distance, army drums echo tunes of revolution.

Two priests in white satin robes plant their feet in front of towering church doors. Patrons gaze from the plaza below while the priests stand silently for photos. Children with gladiolas and men carrying wooden St. Christophers on their shoulders bow their heads as they pass the priests. Shoe-shining Indian boys giggle behind the robes. Three lambs carved out of papayas with furry fruit hair greet people as they enter the church.

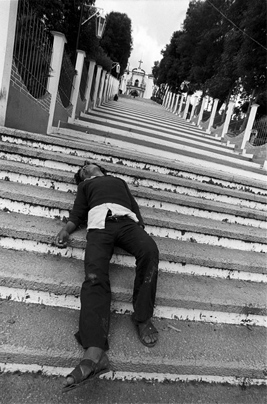

Dozens of steps on the way to heaven. A drunk walks a few and dreams the rest.

They light tires and cardboard boxes. They run through the flames protected by the spirit of Saint Martín. Children giggle. Parents smile. Fumes rise to heaven.

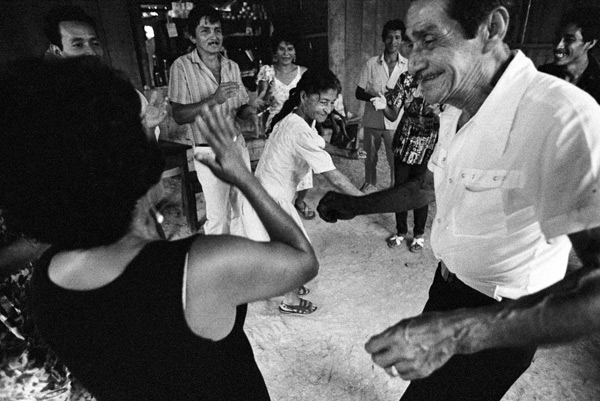

She’s sixty-four and dances like Chubby Checker. Green ruffles at the bottom of her dress twirl when she squats, wiggles her hips, and raises her arms. It’s Mother’s Day on the Amazon, and she shouts her motherhood as she celebrates with her family. She guzzles the beer-egg milkshake and opens her eyes wide. “You drink half, and I drink half,” she insists as she passes the bottle covered with lipstick smudges the color of cotton candy. “For Mother’s Day. To the mothers!”

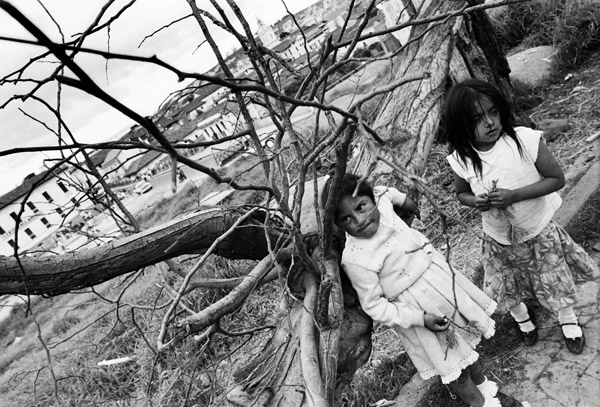

Winding streets and twisted trees in the Old City. The Virgin of Quito looks over the city from the highest peak, guarding the children who stare through those branches.

Tierra del Fuego. The Land of Fire, where before they were extinct, the Fuegians warmed themselves by flames. Tierra del Fuego. The End of the World.

- Follow us on Twitter: @inthefray

- Comment on stories or like us on Facebook

- Subscribe to our free email newsletter

- Send us your writing, photography, or artwork

- Republish our Creative Commons-licensed content