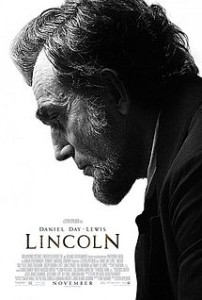

Abraham Lincoln’s 204th birthday is upon us. Although the sixteenth President has never receded from our public consciousness, Steven Spielberg’s recent movie Lincoln has brought him to the front of our minds perhaps more than at any point in recent decades. Most Americans celebrate the man — certainly Spielberg does. But there are some who do not. I’d like to explore some dissenting views in a serious way and offer my own assessment of Lincoln and his historical legacy.

Abraham Lincoln’s 204th birthday is upon us. Although the sixteenth President has never receded from our public consciousness, Steven Spielberg’s recent movie Lincoln has brought him to the front of our minds perhaps more than at any point in recent decades. Most Americans celebrate the man — certainly Spielberg does. But there are some who do not. I’d like to explore some dissenting views in a serious way and offer my own assessment of Lincoln and his historical legacy.

Clearly, the positive view of Lincoln as “The Great Emancipator” predominates in our society and culture, for reasons that are quite well known even to those who know relatively little about American history. There are some, however, who condemn Lincoln’s “tyrannical behavior in trashing the Constitution and waging war on civilians in violation of international law and codes of morality.” While one can seriously debate the constitutionality of Lincoln’s actions on, say, the suspension of habeas corpus, the “Lincoln as Tyrant” viewpoint, typically associated with neo-Confederate sympathies, does not offer well-substantiated analyses of his political career. These partisans worship the Old South and see Lincoln as the man who destroyed it.

But there is another perspective on Lincoln I want to explore in more depth, namely one that criticizes his views on race, which, by today’s standards, certainly reflect real bigotry toward blacks. Understanding Lincoln completely means understanding that he did, for example, publicly support a plan to send freed slaves back to Africa or elsewhere. There are numerous examples demonstrating that he did not view blacks and whites as equals. For more on this view, one can examine Forced Into Glory: Abraham Lincoln’s White Dream by Lerone Bennett Jr. (Interestingly, many neo-Confederate types such as Thomas DiLorenzo often cite Bennett to highlight these criticisms as well, even though their most righteous anger derives from Lincoln’s supposed tyranny. I won’t speculate as to how much they actually care about Lincoln’s racial prejudices.) Reviews of the book by Eric Foner and James McPherson, arguably the two leading scholars of the Civil War/Reconstruction era over the past fifty years, point out significant problems with Bennett’s interpretation as well as some factual errors. Foner’s own balanced take on Lincoln appears in his book The Fiery Trial: Abraham Lincoln and American Slavery.

Although Foner and other scholars have noted Lincoln’s use of the word “deportation” in his 1862 State of the Union address, that address also made clear that any such plan required the “consent of the people to be deported.” Such a statement suggests the word meant something different in those days than it does today (irrespective of Mitt Romney’s notion of undocumented immigrants “self-deporting“). Additionally, in a cabinet meeting that September Lincoln stated clearly that any colonization plan had to be “voluntary and without expense to themselves.”

Nevertheless, the views expressed in Bennett’s work also resonate among those who are skeptical of Lincoln’s legacy for other reasons, including some African Americans. Bennett was an editor at Ebony for decades and published countless articles — including the 1968 essay “Was Abe Lincoln a White Supremacist?” — that laid out some of the themes that later became Forced Into Glory. A friend of mine, a scholar and activist whom I respect greatly, told me essentially that because of the connection she feels toward her ancestors, whom Lincoln viewed as inferior, she cannot honor him as a historical figure. This got me thinking about my own view of Lincoln.

Ultimately, I would argue that the ways Lincoln went against the bigotry of most whites in his day should matter more than the ways he reflected it. More broadly, few major historical figures have done or said nothing that deserves criticism, certainly not any historical figure who has exercised governmental authority. But in Lincoln’s case, surely the good of what he did outweighs the bad. In addition to the actions he took to help end slavery as president, the words he uttered at Gettysburg placed equality at the center of American ideals in a way no other speech has, as historian Garry Wills has argued in his Pulitzer Prize-winning book Lincoln at Gettysburg. Did the sixteenth president mean equality the way most of us do in the present? No. Today, his attitudes would be retrograde. But he didn’t live today. For lack of a better term, when looking at history we should give “credit” to those — especially those leaders — who were more egalitarian than the norm in their own time and, more importantly, acted on their (relative) egalitarianism to make things better for people. We should not expect them to be egalitarian in 2013 terms and mark them down where they fall short.

Still, the matter of my friend’s ancestors bothered me. Could I honor someone who viewed my ancestors as less than equal, even if that person had done great things, even for them directly? I had to go outside my own box to grapple with this. I came to the question of Martin Luther King Jr. and gay rights. It’s not exactly the same thing as Lincoln and his view of African Americans, but it offers some reasonable parallels. I did a bit of research and found this:

The only time King publicly mentions homosexuality was in 1958 while answering a question in his advice column in Ebony magazine in which a boy asked:

“I am a boy. But I feel about boys the way I ought to feel about girls. I don’t want my parents to know about me. What can I do?”

King answered: “Your problem is not at all an uncommon one. However, it does require careful attention. The type of feeling that you have toward boys is probably not an innate tendency, but something that has been culturally acquired. You are already on the right road toward a solution, since you honestly recognize the problem and have a desire to solve it.”

Rev. King did not condemn homosexuality in terms anywhere near as harsh as many contemporary religious leaders. Nevertheless, he clearly identified homosexuality as a “problem” that needed to be solved, as well as one that results from culture rather than something innate to a person. From a policy perspective, it is virtually impossible that he would have, at that time or at any point before his assassination in 1968, embraced gay marriage. One could thus make an argument that because of Rev. King’s views on homosexuality, one cannot view him positively as a historical figure. I could not accept such an argument. It does not make sense to judge his views based on today’s standards, and such a view ignores the larger importance of what he did for equality, as well as how those actions ultimately benefited the LGBT community. We also don’t know how Rev. King’s views on this issue might have evolved over time, had he been given the chance.

The same points apply to Lincoln and his views on race. His views did evolve over time, and he even called for a limited voting franchise for black males in his final public speech before his own assassination. In response to that final speech, John Wilkes Booth declared to a friend: “That means n—— citizenship. Now, by God, I’ll put him through. That is the last speech he will ever make.” Who knows how much further Lincoln would have evolved after 1865? For example, it seems impossible that Lincoln would have opposed the Fifteenth Amendment, passed in 1870, that banned any race-based restrictions on voting rights.

Yes, it is important to know the full picture of Lincoln. That’s what history is about, not hero worship. Nevertheless, I would argue that it’s unfair to look at history solely from the perspective of one’s own ancestors because doing so implies that what a historical figure does or believes regarding one’s own ancestors (broadly defined) matters more than what that person has done or thought regarding all human beings. Additionally, judging people solely on how their views compare to those of the present is equally unhelpful. Who knows how people in 200 years will judge even our most egalitarian ideas today? Whether we are talking about Martin Luther King Jr., Abraham Lincoln, or any historical figure, a person need not be perfect in order to be great.

Ian Reifowitz Ian Reifowitz is the author of Obama’s America: A Transformative Vision of Our National Identity. Twitter: @IanReifowitz

Dear Reader,

In The Fray is a nonprofit staffed by volunteers. If you liked this piece, could you

please donate $10? If you want to help, you can also: