Where to begin? Any street here in Ho Chi Minh City hits you with so much in one minute.

You cower from the onslaught: braying horn honks shattering nerves, motorbike engines sputtering and growling, and any number of the 10 million Saigonese moving, squatting, smoking, spitting, buying, selling.

A swarm of kids tumble out of school, mindless of the ceaseless maelstrom of traffic in the street. The red neckerchief of state obeisance, dutifully knotted around their necks hours earlier, is now used to play-whip a friend.

And, most difficult of all for an Englander like myself, nowhere is there no people and no noise. There is only the millions of people; the bike fumes; the money passing hands; the beggars, with tireless hope, thrusting out empty paws; and the burgeoning vehicle hierarchy: a drip-drip influx of sport utility vehicles (SUVs) and Mercedes Benzes beeping the bike-riding lower classes out of their way, only to ultimately be rejoined by them at the lights. For with four million motorbikes in this city alone, we are too many, and the archaic road system here cannot cope with our luxurious metal excesses. Communism’s nouveaux riches are as vulgar and cocooned from reality as ever.

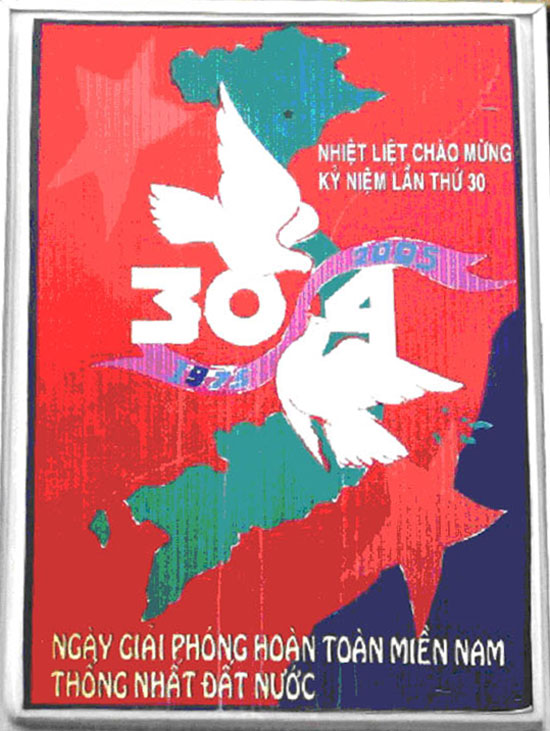

Here, in the city formerly known as Saigon, lives are lived on top of one another. Hard-won possessions and houses are guarded by ever-watchful owners, utilizing a variety of padlocks, barbed wire, iron spikes, or walls lined with broken glass. It’s a mindset that dates back to April 30, 1975 — the day of the city’s fall or liberation, depending on your perspective. And that perspective depends, at least in part, on your roots.

The Red thread

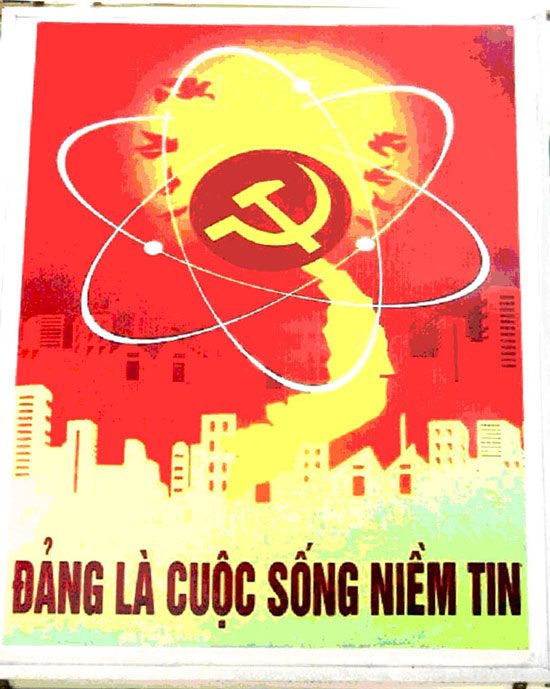

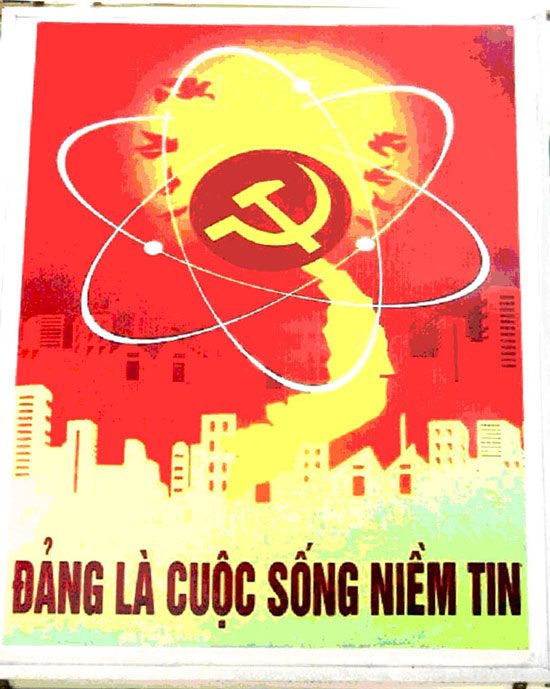

The communist nature of daily life here is something you could easily miss when passing through as a tourist on the group tours, with the state-owned tour companies and hoteliers pointing out all the glorious deeds of once-dear leader Uncle Ho. Yes, you’d see red flags, yellow stars, and the lime-green uniforms of army-cum-police on every street. You might even see some of the old Tannoy speakers on street corners in Hanoi, and experience the misery of being woken by the blare of propaganda at 6:30 a.m.

But it takes time to see how communism and a closed society has imprinted itself into the habits and thought patterns of the people through education, controlled media, and fear. Who would dare discuss politics when the man beside you in the coffee shop could be a plain-clothes policeman? People still disappear to be “re-educated” after visiting the wrong websites, such as Vietnamese pro-democracy groups in the United States, for example.

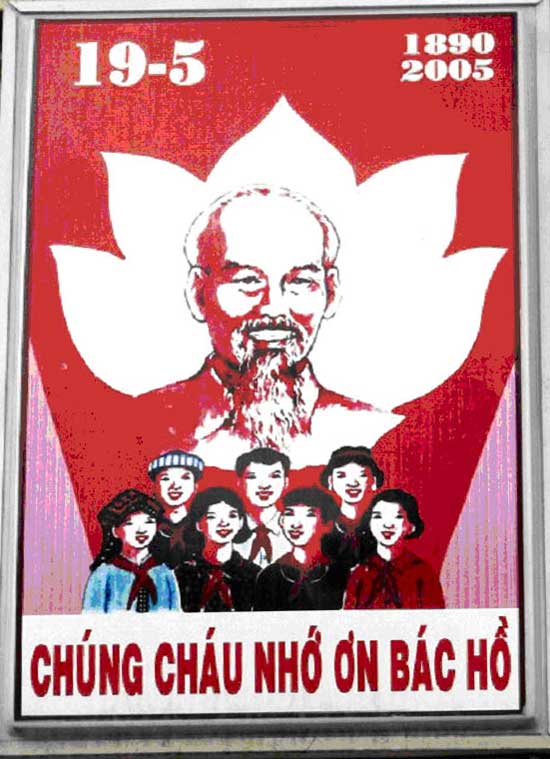

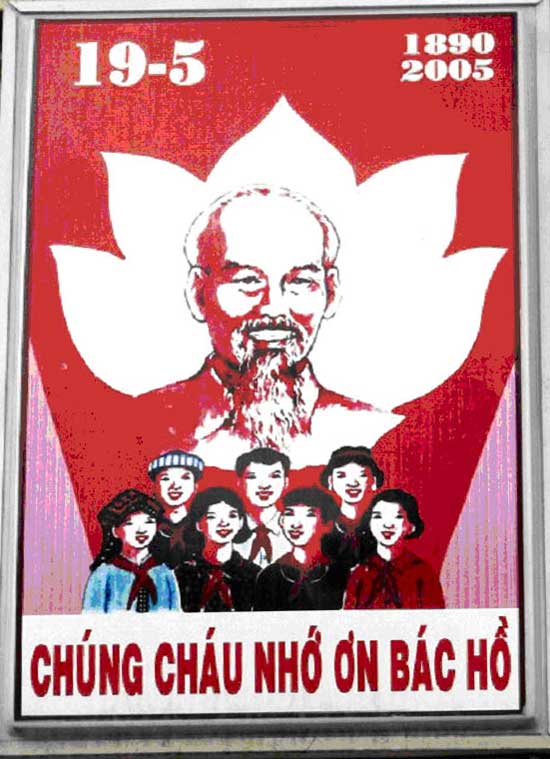

Four years of teaching and writing in Vietnam has put me in proximity with this much-exalted “youth.” From 2004 to 2008, I taught students from across the entire age spectrum; that’s preschool (kindergarten) through to adults taking night school classes after work. But the majority of my time was spent in private language institutions, teaching high school kids aged 12 to 18. They are a unique demographic, brought up on brainwashing, educated in a doctrinaire manner to revere Uncle Ho and to never question the status quo.

The adolescents I taught are still very much a product of their closed society. From my tentative discussions with them in class, I learned that they are rarely exposed to the choices and responsibilities of their Western counterparts that engender maturity. Their parents generally seek to protect them from “social evils” — drugs, prostitution, sex — sometimes forbidding them to date boys or girls until they’ve graduated from university. One of my female students — an 18-year-old named Vinh — once told me that, over the weekend, her mother had listened in on her private phone call and locked her in her room when she heard her discussing boys.

But despite the iron-rod parenting and societal frowns, Vietnamese teens are still having sex, and doing so in ignorance of safe-sex practices. The country has one of the world’s highest abortion rates, at 1.4 million annually. Due to the lack of privacy in Vietnamese society — children tend to live with their parents until they marry — couples often head at night to ca phe oms (literally, coffee shop hugs), which have lightless rooms out back for making out.

Yet the closed society is open to bizarre paradoxes. Slushy romantic notions of love are idealized, and every teenager knows the lyrics to the Titanic theme tune, “My Heart Will Go On.” Students in their mid-20s will giggle at words such as “hot” or “sexy.” Trying to have a debate on gender, race, or sexual politics is fraught with difficulties, and a discussion of politics in general is simply not possible.

The doctrinaire education system has created a population that lacks a vital vocabulary for critical thinking. It’s staggering, the lack of responsibility and social awareness the youth here has. I could cite several examples from my time teaching high school graduates English: the 18-year-old girl, Na, who told me that the first time she had raised her hand to ask a question in class was in mine; one student’s reaction to my circuitous questioning regarding ideas about freedom of the press:

“Who controls the media in Vietnam?” I asked her.

“The government,” she replied.

“Is that a good thing or a bad thing?”

“It’s a good thing.”

“Really. Why?”

“Because our government wouldn’t lie to us.”

Where would one begin? For if the children are receiving English lessons in a private school, it often means their parents are paid-up members of the Party.

This education system, serving only those in power, is starting to take its toll on foreign investors, who are experiencing firsthand the problems that inculcation and rote learning have in the workplace. Vietnam has experienced phenomenal gross domestic product (GDP) growth in the past decade, making it the second fastest growing economy in the Southeast Asia region. There is a growing gap, however, between skilled jobs and a skilled workforce able to make decisions, take responsibility, and lead.

Human resources headaches for foreign investors

Vietnam is at a crossroads. The country became a full-fledged member of the World Trade Organization (WTO) on January 11, 2007, and is opening up to a market economy. However, WTO commitments restrict the hiring of foreign workers in some areas, notably the service sector. Therefore, the inability of the current generation of graduates to solve problems and make decisions through critical thinking is now surfacing as a headache for foreign investors in the human resources sector. At the Vietnam Business Forum in Hanoi last December, the Australian Chamber of Commerce (AusCham) bemoaned the fact that few graduates had the necessary skills to enter the workplace without additional training. AusCham cited a lack of focus on analytical skills as one of the major shortcomings of Vietnam’s higher education system.

In March this year, according to the European Chamber of Commerce (EuroCham), foreign investors bemoaned the shortage of skilled workers to fill roles in their companies. EuroCham board member Mark Van Den Assem was quoted as saying that young personnel were usually not confident enough to take over managerial posts, while subordinates doubted their capabilities.

Critical thinking skills are vital for effective problem-solving and decision-making, since they allow individuals to react in a balanced way to difficult situations by weighing the evidence and responding in a measured and beneficial manner. In addition to intellectual skills, other traits found in good critical thinkers include empathy, humility, and autonomy.

The devil reads Pravda

“A great deal of intelligence can be invested in ignorance when the need for illusion is deep.” Saul Bellow’s words have a timeless application to the act of governance, be it spin-doctoring in a democracy or propagandizing by the “Ministry of Truth” in an Orwellian-style totalitarian state.

Such practices are something I witnessed daily when I began working as a freelance writer and subeditor for one of Vietnam’s state-owned newspapers in November 2007. The paper, Thanh Nien, is a national English-language version of the Vietnamese edition, published by the elaborately titled Forum of the Vietnamese Youth Federation. Indeed, some of the subtle manipulations of “the truth” fall into my hands as subeditor and “reporter.”

Thanh Nien is one of the freer media outlets in terms of its editorial policy. “Freer” basically means that it is allowed to run corruption stories: the chief of police who took bribes, the minister receiving bulging manila envelopes in order to fast-track a construction project, land reclamation scandals, and so on. It’s a long and growing list. Such stories give the illusion that the endemic, deep-rooted corruption is being tackled.

The paper’s name translates as “Youth,” as does its main print rival, Tuoi Tre. Youth is an important concept in this still insidiously communist country. Youth means the future propagation of the old Marxist ideals. Indeed, Vietnam can only have been one of a handful of countries to celebrate Marx’s 190th birthday.

At work, I sit down to edit stories of war heroes, decoding “Pham Xuan An: American leaders continued to blame each other for intelligence leaks covertly orchestrated by the stealth Vietnamese mole.” Such stories are plucked straight from the Vietnamese edition and mean nothing to the foreign readership of the paper. But orders come from higher up to leave page four free for the 14th episode of such inspirational espionage. My stories are summarily bumped with a shrug from the page editor, and I already know why.

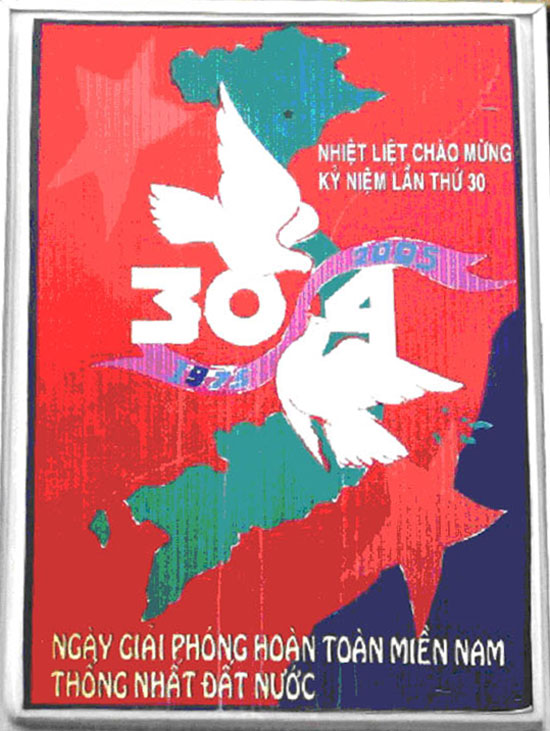

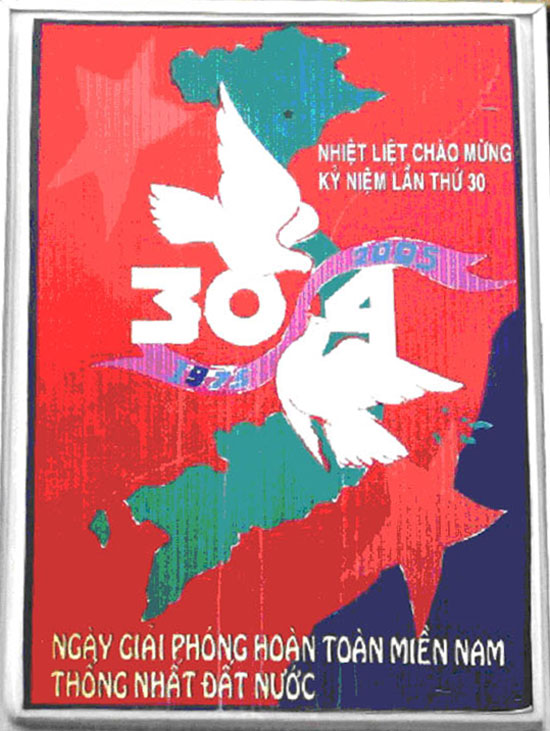

The April 30 holiday, these days tellingly relabeled as “Reunification” Day, is approaching. The State is reminding the population which side won, while the army reasserts its presence in the city. These bored young recruits, many on national service, choose easy targets, such as old ladies hawking fruit on the streets or impromptu street noodle stalls. Such illegal vending is tolerated for 10 months of the year, either through some kind of kickback or sheer wiliness on the vendor’s part. But now a point must be made to the population at large. Now is the time for a sharp reminder from the puppeteer still pulling the strings. So the propaganda posters go up, noting that triumphant date with the classic symbol of a white dove flying above the “Reunification Palace.” And the tools of someone’s livelihood are seized — tables and chairs, pots and pans, bunches of bananas.

Earlier this year, an old regional sticking point, the Spratly Islands archipelago in the South China Sea, reared its head in the news. Territorial ownership is asserted by half a dozen countries in the area, including China, Taiwan, and the Philippines, although Vietnam has the strongest claim to these islands. Interest is piqued by the rich fishing stocks and reserves of oil and gas the archipelago possesses. In March, China began making noises about its rights to claim the islands — a country that, in 1988, was involved in a naval battle with Vietnam off one of the reefs.

At the time I was teaching Business English to university students, and one young man, Trinh, decided to do a class talk on the Spratly crisis. He brought in maps, Wikipedia references, and newspaper cuttings to show why the islands were rightfully Vietnam’s. The class applauded his jingoistic stance, a carbon copy of the nationalistic propaganda that the papers were full of at the time.

Bypassing the information superhighway

Fast Internet connections are widely available today and cheap in all urban centers. The only sites blocked are those to Geocities, where the Vietnamese overseas community has its pro-democracy sites. Such activists are now inevitably labeled “militants” and “terrorists” in the Vietnamese press.

But, thanks in part to the lack of English skills at higher levels, most sites like the BBC and Google are not blocked by a China-esque firewall. One would hope that this might mean some of the ideas about freedom of the press and democracy might make it though.

And yet this is a country that since 1975 has actively encouraged suspicion. It’s the ultimate neighborhood watch scheme. Everyone spies on each other and reports suspicious activity to the police. It is an inversion of Thomas Jefferson’s oft-quoted phrase: the price of un freedom is eternal vigilance.

All this may sound like a lot of 1950s McCarthy-era paranoia, as I myself thought when I first arrived, until I began to be followed to and from the newspaper. Each day, the same motorbike taxi driver (known locally as xe oms) began to appear either outside my house or outside the newspaper whenever I was there. It was sinister, unnerving. Par for the course, an Australian colleague said.

A life less ordinary

So, at times I find myself terrified and tested — when the heat is drawing out beads of sweat by the hundreds, and the bike horns, car horns and, worst of all, bus horns, are bursting my eardrums, scattering my patience and shredding my nerves. At those times I despair for what Vietnam has already become, and what it will be like 10 years hence.

At times I find myself enlightened and elated — a trip to a local temple alive with Buddhist chants, chance encounters on the street, how the city’s pollution turns the sun into a ball of red fury as it sets on another wearying day.

And, after four years, I would say that the key to unlocking the city is this: Despite all the accoutrements of capitalism that have accompanied its phenomenal economic growth in recent years — SUVs, mobile phones, laptops, Wi-Fi hotspots — Vietnam is still is starkly, unpleasantly totalitarian.

The roots of propaganda are sown young and sown deep. Some of the most highly educated and well-traveled Vietnamese people I have met here, including lawyers, doctors, and business people, have all reverted back to a potent, disturbing nationalism when any issue that portrays Vietnam in a negative light has been raised.

Vietnam, number one. Ho Chi Minh, number one.

That’s the country’s myth and mantra. And it’s what the youth are sticking to, at least for now.

In The Fray Contributor

Dear Reader,

In The Fray is a nonprofit staffed by volunteers. If you liked this piece, could you

please donate $10? If you want to help, you can also:

Seeking the zen of the present moment.

Seeking the zen of the present moment.