"Ladies, ladies!" A tall black man calls out to the two girls swishing down the sidewalk in short skirts. "Reggae bar, right here, come with me!"

The girls stop and turn toward the man. Behind them, the neon signs of nightclubs buzz. People of all accents and colors stream past, laughing and joking. "You got free drinks?" asks the brunette. Her face is round, her accent American. In her heels, she’s almost as tall as the man.

"Free entry all night!" says the man, throwing an arm around the girls’ shoulders and tugging them toward the bar.

The two young women don’t budge. "You got free drinks? For girls?" the brunette asks again. "We only wanna go if you got free drinks."

"Don’t worry, baby," the man says. His voice is deep and rich, the vowels rounded by a faint accent. "For you, it’s the first drink free. For a beautiful woman like you."

She remains skeptical. Her friend, a thin girl with wild, curly hair, takes one of the bar’s advertising fliers from the man. "Yeah, it says that here," she points. "It says, ‘First drink free,’ see?"

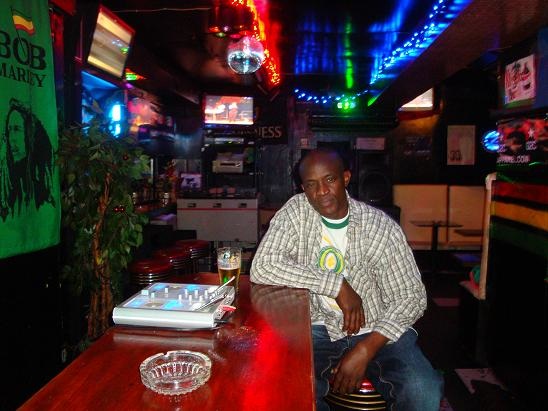

The brunette relaxes. The man, Danny Lekson, grins. The girls allow themselves to be led toward the bar, located on the fourth floor of a Tokyo highrise. The elevator doors close with Danny crowded between the two girls, his smile visible a second longer than theirs.

Nearly 40 years old, Danny Lekson works as a street caller – a man who pulls customers into bars – in an area of Tokyo called Roppongi. By day, Roppongi is a testament to Tokyo’s cosmopolitanism. Art museums, business offices, and luxury shopping plazas sparkle like jewels in the city’s international crown. But as dusk descends, the district transforms into a notoriously seedy meat market, where American military men prowl for willing women and international businessmen blow off steam at all-you-can-drink strip clubs. Danny works as one of the dozens of Nigerians who line the streets at night, shucking fliers and tugging the sleeves of passersby, pushing bars with cheap drinks and easy women. To the ex-pats who frequent the area, the group of tenacious Africans is "the gauntlet," a column of men whose solicitation, some say, borders on harassment.

Roppongi, with all its foreign faces, is an anomaly in a country that has traditionally prided itself on its unique, homogenous culture. For decades, Japan refused to open its borders to foreign influence until the American navy wrenched them apart in 1854. Today, at roughly 1.7% of the the population, immigrants are a tiny minority in the country. But as birth rates drop and the work force grays, many Japanese are calling for efforts to increase immigration. New people with new skills, the thinking goes, are needed to sustain the competitiveness of the world’s second largest economy. But the government has made it clear that Japan is not throwing open its gates to the huddled masses just yet. In the wake of Japan’s soaring unemployment rates during the recession, the country is seeking skilled, specialized immigrants.

The men who work as street callers, most of whom are Nigerian, are seen by some to be the exact opposite of the kind of immigrants Japan desires. Nigerians have always represented the largest African population in Japan, and their numbers have been steadily increasing every year. In 2007, the population consisted of 2,523 legal residents. "Roppongi is now virtually a foreign neighborhood," the governor of Tokyo, Shintaro Ishihara, complained in 2006. "Africans – I don’t mean African-Americans – who don’t speak English are there doing who knows what."

Often, other foreigners are no more sympathetic. One American, a ten-year resident of Japan, sees the street callers as banished criminals of shadowy provenance. "Those guys in Roppongi, they’ll cut your throat for a dollar," he said. "They all used to be in Nigeria carrying machetes on the street. And most of them can’t go back. That’s like being the worst guy in prison, getting kicked out of Nigeria."

Simon Ewuare, a 29-year-old Nigerian who came to Tokyo seven years ago, doesn’t dwell on such comments. To be successful in Japan, he tells newcomers, you can’t "think about if they hate you or not. Put it out of your mind."

A soft-spoken man with small town manners, Simon covers his solid frame with brand new Rocawear jerseys and bleach-white Nikes. But he wasn’t always so stylish. As a young man, he did, in fact, carry a machete back in Nigeria – but it wasn’t on the street, and it wasn’t for long. As the eldest son of a well-off cocoa farmer, Simon was expected to apprentice under his father and eventually take over the business. But the thought of spending the rest of his life cooped up in his family’s little village made him want to run far away. So he did. In his late teens, he ended up in Benin City, a coastal capital known as the home of some of Nigeria’s most esteemed universities. With a cousin, he started a transport business. Soon, one semi-truck multiplied into five, all busy hauling goods across the hills of Nigeria.

By the age of 22, Simon had become a self-made businessman. He began wondering what he could do abroad. "I actually got a visa to America," he says, with a trace of pride. "But I talked to some friends there and they said, ‘It’s so hard here, the money’s not good here.’ So I talked to friends in Japan. They said, ‘Come here, it’s good here.’"

When Simon first arrived on a three-month sightseeing visa, he was taken care of by relatives and friends who had come before him. The African community in Tokyo is tightly knit. In some cases, it’s as if entire swaths of villages have been uprooted and transplanted: brothers live together; cousins work together; and friends who used to attend the same primary school back in Nigeria go out drinking together. In an exceptionally lucky break, Simon knew a Japanese man who had worked with his father in Africa and who agreed to be his guarantor, a person or company required by Japanese law to be responsible for an immigrant who desires certain kinds of residency or work permits.

Danny Lekson, the bar caller in Roppongi, was not so lucky. After his three-month sightseeing visa expired, he stayed. Despite the risk of detainment and deportation, he’s not the only one who has made such a decision. At any given time, there are estimated to be more than 91,000 immigrants living in Japan on overstayed visas. Visa-related arrests make up a significant percentage of the crime that foreigners commit in Japan, and contribute to statistics that, compared side-by-side with the crime rates of citizens, make it look as if foreigners are much more dangerous than Japanese natives. Though the numbers are endlessly contested and re-interpreted, many people agree that excepting visa-related offenses, the crime rates of foreigners and natives are nearly equal. For five years, Danny lived in Japan without a visa, hopping from factory to factory. Before emigrating to Japan when he was 28, he had studied international relations and had worked as a journalist. Spending hours stamping sheet metal and walking on eggshells around bosses who could deport him at his first mistake was not the life abroad he had envisioned.

His salvation came at a Shinjuku club, in the form of an attractive Japanese woman named Yayoi. The two hit it off, and eventually, she agreed to marry him, despite his illegal status. The couple walked down to the local municipal office and announced their intentions. "How it works is, they take you to one room, and make you sign a paper about getting deported," says Danny, wearily rubbing his eyes. "And then you go into another room, and you sign a paper that says you are on probation."

The marriage loophole is a route to legality that many overstayers have taken. "They want to marry us," Danny says about the dozens of Japanese women who have African husbands. "I don’t know why." He pauses. "If you want to stay, there is almost no other way."

For Danny, marriage did not work out so well. After a few years together, his wife petitioned for divorce while he was visiting family in Nigeria. They no longer speak, but their seven-year-old daughter, Olucha, is a reminder of their time together. According to Danny, Yayoi refuses to let him see Olucha. In another long-standing point of contention between Japanese and foreigners, Japan affords foreign parents almost no custodial rights in the case of mixed children. Although Olucha lives just a few train stops away from Danny, he can’t remember when the last time he saw her was. Every time they talk on the phone, her English ability has faded a bit more. "They paint her with their native food and language, you know," he says. "I speak to her in English. She understands. But sometimes I call, and she doesn’t understand."

In a bar owned by his younger brother in Roppongi, Danny introduces me to his friend Michael, a 32-year-old dressed like a member of the ’80s hip hop group Run-DMC, in a black fedora and a snug leather jacket. Michael also works in Roppongi, where he says he makes about $45,500 a year as the manager of a strip club. He’s reserved but polite, and sits at the bar chain smoking. When I ask what town he’s from, he says, "Igbo," naming the second largest tribe in Nigeria.

Michael, who came to Japan three years ago, is married to a Japanese woman and has a two-year-old daughter. He shows me a picture of her on his cell phone: a delicately featured girl with skin the color of rain-soaked suede, staring up from the screen with eyes as bright as her smile. Michael’s interest is piqued when he learns I work as a kindergarten teacher at a Tokyo international school (where, for the sake of comparison, the average teacher earns about $9,000 less than Michael). "It’s all in English? They learn English?" he asks. "How much does it cost?" I tell him it’s $7,500 a year (later, I realize it’s more like $14,000 a year). He nods slowly, considering the price. "That’s ok, I can do that," he says. "If it’s in English." While Michael works, his daughter stays home all day with her mother, who speaks Japanese. Michael speaks English. He and his wife get by with the few words they can speak of each other’s language. But when Michael talks to his daughter, she can’t understand a word he says.

Simon, the well-dressed cocoa farmer’s son, was also married to a Japanese woman. Though they didn’t have any children, their relationship also ended in divorce. From the beginning, he says, her family did not accept him. "Her father took me [aside] and told me that it would not last," he says. But he wasn’t concerned; that’s how fathers are. "Even my own sister, she married a Nigerian man, but our father didn’t like him. But then later it’s ok, he’s accepted." His wife’s father didn’t end their marriage, but the couple’s differing goals did. She wanted to move to Norway, an idea that puzzled Simon. "Why do I want to go to Norway?" he asked her. "I am already a foreigner here, why do I want to go be a foreigner in Norway?"

Simon had a reason for wanting to stay in Japan. With the freedom of a sponsored visa even before he met his wife, Simon had been able to attend a Japanese-language school for two years while working nights at a restaurant. He had become confident enough in Japanese to begin thinking about doing what he did best: starting his own business. Just as he had turned to a cousin in Benin City to learn the transportation trade, he turned to a cousin in Tokyo to learn the clothing trade.

If Roppongi is where clothes come off, then Harajuku is where clothes are bought. The area, made famous overseas by Gwen Stefani and her Harajuku Lovers clothing line, is the heart of Tokyo’s reputation as a fashion free-for-all. Its main artery is Takeshita Street. On any given day, Takeshita Street is crammed with Japanese school girls and foreign tourists gawking at stores selling gothic Little Bo Peep costumes and vinyl sexy nurse outfits. To Simon, it was the perfect place for his shop: It was where people went to spend money.

Simon set his sights on the hip hop clothing business. The baggy style of urban America found a following among Japanese youth in the late 1990s. As fashion and rap music became increasingly intertwined, "hip hop shops" began sprouting up all over the city. For the Japanese trendsetters who could afford to pay $300 for a pair of sagging shorts, the presence of black employees made the shops’ image all the more authentic.

But Simon did not want to be a mere employee. He wanted to be the owner.

He had had only brief exposure to the intricate business customs of Japan, observing what he could while busing tables and chopping vegetables at the restaurant where he worked. His Japanese ability was far from fluent. And he was a foreigner. But he held tight to something he had learned when he arrived as a teenager in Benin City, as an immigrant on a ticking tourist visa in Tokyo, and as the unwanted son-in-law of a Japanese bride: "In the beginning, everything is difficult."

The first obstacle was securing a location on Takeshita Street. As one of the most heavily trafficked areas in the city, it was prime real estate. With the "gift money," security deposits, and advance rent that Japanese realtors demand upon signing a lease, the shoebox-sized space he had his eye on would cost nearly $60,000 upfront. But money wasn’t the problem. Simon paid in cash, wiring the money from an account in Nigeria where he had saved his profits from the semi-truck business. The problem was getting the realtor to take him seriously as a client. "They see you’re a foreigner, and they say no, they want to skip you," he says. He went about finding Japanese people who were willing to be paid to act as the face of his business. "You get some of their own people and push them forward, and then it is ok."

To Simon, this kind of adaptation is not a big deal. "A lot of foreigners complain," he says. "But Japanese are good people. In Nigeria, too, there are different groups of people. Everyone is different." In Simon’ home country, conflicts between the northern Muslims and the southern Christians have persisted for years, sparking riots every few months that kill hundreds at a time and displace thousands. If all he has to do to reach his goals is let the Japanese find comfort by dealing with other Japanese faces, then he is more than willing.

After only a couple of years in the clothing business, Simon was successful enough to open a second store in Tokyo and bring his brother over from Nigeria to staff it. Though he ducks his head bashfully when asked how much his business makes – "We only just met!" he says, practically blushing – he can afford to pay the $2,700 monthly rent on his Harajuku location, the $28,500 he says he pays each of his three street callers, the $45,500 salary his brother earns as a store manager, along with dozens of other expenses, and still have enough money left over to save for his next venture: a filling station in Nigeria.

The money that can be made by young, ambitious immigrants in Japan is seemingly endless. In some cases, it’s enough to lure them from other foreign countries. Michael, the father of the two-year-old who can’t understand him, previously tried his luck during a four-year spell in Switzerland. But conditions in Japan are better, he says. The most he could ever hope to make in Geneva was only $26,000 a year, almost half of what he makes now in Tokyo.

To some foreigners, especially those from developed countries, the entrepreneurial activities of the Nigerians indicate greed. "They don’t care about the culture of Japan," says one English teacher. "They’re only here to make money." But Danny Lekson says foreigners from rich countries don’t understand the circumstances behind his financial ambitions. When "an African makes money," he says, "it’s not for me alone. There are so many people looking up to me. So [$2,700 a month as a factory worker] is enough for me, but there are still problems back home. My nieces and nephews need pocket money in school. I have to pay for so many people back home." In Nigeria, Danny owns three homes. All of them house his extended family members.

Traveling across the world to be the main breadwinner for a dozen or more family members takes more than courage and a sense of adventure. It takes money. The average price of a one-way ticket from Lagos to Tokyo is around $1,500, and in the world’s most expensive city, charges pop up like inflatable boxing toys. Danny Lekson and Simon Ewuare both come from relatively well-off families in Nigeria. In a country where only slightly more than half of the children attend even elementary school, both men attended high school. Danny even went on to earn a four-year university degree. Talking about people like Simon, who attended a language school while working part time for two years, one Senegalese man says, "Any time you see Africans studying in Japan, they come from rich families."

Despite Danny’s education and Simon’ ambition, both of them are just anonymous faces in the crowds of Nigerian street callers that some characterize as nothing more than brutal thugs. Last year, the American Embassy issued a warning about partying in Roppongi after a string of incidents involving tainted drinks and stolen credit card information. Foreign users of an online forum about Japan immediately fingered Nigerians as the culprits. In one of the tamer comments, a user advised, "Avoid all Nigerians in any way, shape or form." Another described a scenario in which "a mate" followed a Japanese man to a bar, only to be confronted by an empty room until "out of the darkness half a dozen huge Nigerian dudes appeared" and demanded money. He lamented the injustice of the situation, explaining his friend was "an affluent hard-working professional who had been in Japan for over 10 years" while the supposed aggressors were "filthy african [sic] illegal immigrant [expletives] who had probably arrived on a plane from that [expletive] continent that very morning." To explain the lack of evidence connecting Nigerians to the drink-spiking incidents, users accuse the Japanese police force of indifference to crimes targeting foreigners.

Of course, not all of the foreigners in Tokyo are as obviously prejudiced as users of that message board. Wikitravel, the travel guide offshoot of Wikipedia that is updated freely by site users, blames the drink scams on seductive foreign females hired by disreputable bars rather than Africans working in the area. But all of the sources are right about one thing: crime does exist in Roppongi and, like every group in the area, the Nigerians have perpetrators among them.

One evening, a couple hours into his bar-calling shift, Danny and I walk into Don Quijote, the foreign-import emporium near his post on Roppongi’s main street. It’s the middle of allergy season in Tokyo, and Danny has had a raspy cough and itchy eyes all day. If it keeps up, it’s going to be a long night. As we walk into the store, Danny heads straight to the back, toward the medicine supplies. I linger near the entrance, distracted by a large display of makeup imported from America. After a couple of minutes, I scan the aisles for Danny, but he’s nowhere in sight. I choose a tube of mascara and wait my turn in the checkout line. As I receive my change from the cashier, my cell phone rings.

"Where are you?" Danny asks. I tell him I’m at the checkout, and walk a ways toward the back of the store, where he is. He comes toward the front. We meet in the middle. "You want me to buy you something?" he asks. He scans the area and offers the nearest, cheapest item, Japanese sweet potatoes roasting inside a heated glass case that cost a dollar each. "Here, you want a potato?"

"No, I’m fine," I said. "I already bought something, that’s why I didn’t see you."

"Oh, you bought something?" he asks, still scanning the area around us. "Ok, so let’s go."

Once we’re out of the bright store and back on the dark sidewalk, Danny opens his hand to reveal a tube of allergy-combating nasal spray. Maybe he bought it while I was looking at the mascara, I think, but I doubt it. He pulls a crumpled Don Quijote shopping bag out of his pocket and puts the tube inside. I wonder if he carries the shopping bag with him all the time, or if it’s shared among his friends.

I am surprised he is so trusting of me; earlier that night, it wasn’t the case. While we sat drinking and talking in his brother’s bar, an older Nigerian man had flung the door open and scanned the dark room. The moment he spotted Danny, the older man strode up to him. He had the kind of crazed eyes and ecstatic grin usually only seen with people high on stimulants, even though drug use is very low in Japan. He held a yellow plastic bag containing something heavy. He gave it to Danny, who peeked inside and then handed it off to another man. The man looked down at the object, raised his eyebrows, then stashed it behind the bar.

"What was in that guy’s bag?" I asked.

Danny barely hesitated before he answered, "Ah, some special wine, I think, some secret expensive wine."

A couple of minutes later, I asked Michael, Danny’s friend who had been interested in sending his daughter to international school. "Personal electronics," he said from behind his cloud of cigarette smoke. "A car stereo, I think."

It became slightly easier to understand how the governor of Tokyo, during an interview with the foreign press, could assert so nonchalantly that the presence of Africans in Roppongi is "leading to new forms of crime, like car theft."

Over on the other side of Tokyo, in Harajuku, Simon finds out his story will be told in the same article as Danny’s story. He is furious. "We are not the same people, I am not a Roppongi person!" he roars. Besides his rueful ruminations on Nigerian politics, it’s the only time he’s been anything but politely accommodating. "You say we are all Nigeria, but we are not the same! Even I, when I come here, even I am surprised about Roppongi!" But his anger soon fades to weary appeals: "Please, please, tell them I am not in that business, of the credit cards and this, it’s not for me. For me, you like the clothes, you buy them, if you don’t, you don’t!" He is, understandably, desperate not to bring any disturbance to his business: it is his future. He sees his life in Japan as an arrow aimed toward a secure, relaxed retirement in Nigeria. His profits have been bruised by recession-tightened fists, and he looks forward to opening an economy-proof petrol station in Africa. "I don’t want any trouble, I just want to do my business here," he says to me, pleading, "and then go home."

In The Fray Contributor

Dear Reader,

In The Fray is a nonprofit staffed by volunteers. If you liked this piece, could you

please donate $10? If you want to help, you can also: