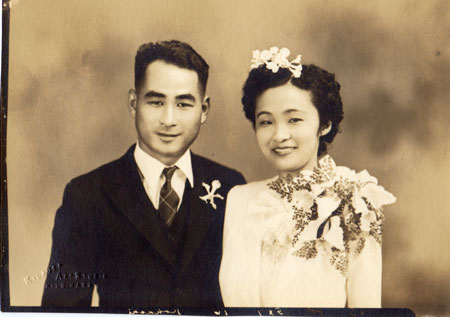

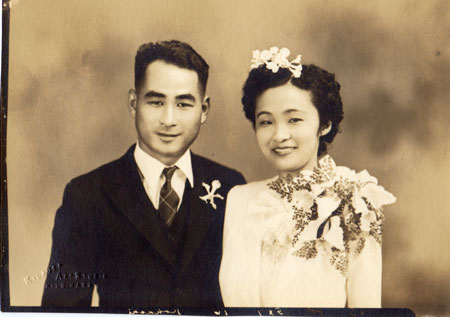

The perfect couple on a spring break cruise in March 2004. Photo snapped by Lindsey’s mom, who considers Todd her “adopted son.”

I met Todd on a curb outside a Target store. When I heard a high-pitched squeal reminiscent of sixth grader, I instantly knew I found a friend. It was all part of Michigan State University’s freshman orientation. They welcomed us with shopping bargains; I came home with a catch.

When Todd, my friend Danielle, and I exchanged phone numbers on the bus ride back, I knew Todd wouldn’t call Danielle; he would call me. Unlike Danielle, Todd and I both knew our exchanges weren’t a regular pick-up attempt. He called that weekend.

Todd was born and raised in Chassell, Michigan. You’ve probably never heard of Chassell because it’s located so far north in the upper peninsula of Michigan that Todd could basically reside in Wisconsin. Although Todd doesn’t have a yooper (the name by which downstate Michiganders refer to Upper Peninsula dwellers) accent for some odd reason, when he’s feeling festive, he will whip out his impersonation of an average yooper’s slang: “Aaaaayyyy, let’s go in da howuuuse.” His hometown is so small that Todd graduated with 23 people, including himself, and had to drive an extra 20 minutes every morning to get to the closest school that had a pool for swimming practice.

“They don’t like anyone who’s not like them,” Todd says of his family. “White, middle-class Americans.”

I imagine the conservative and religious Sauvola clan embracing me, fawning over the perfect daughter-in-law, except for the fact I’m gay.

Why don’t they have straight rallies?

Although fast friends, Todd and I took two months to come out to each other. Our discomfort showed in our hesitation at attending the annual Gay Pride rally held directly across from my apartment complex. Despite a little skepticism — “Do they have straight rallies?” we’d asked each other — we walked over.

There were men in leather g-strings, protestors outside the fenced area screaming we were all going to hell, and the two of us— confused, new to the scene, and somewhat bothered by the fact that there were 3-year-olds present.

Quickly, however, we came to appreciate the sense of unity a Pride rally can provide. Everyone there was either LGBT, or accepting of our lifestyle, and damn, it felt good.

Michigan State has come a long way when one considers that 50 years earlier, rather than gay pride rallies, two massive purges took place on campus, in dorms where Todd and I might have lived. Police ransacked gay persons’ homes, arrested them, and forced them out of college.

Witnesses told of friends who were handcuffed and taken in for lie detector tests to determine their sexuality — as well as their future careers. Two professors were “excused” from their teaching responsibilities, while nearly 30 men were harassed or contacted by the police.

Today the campus, like much of America, has changed. According to Michigan’s Triangle Foundation, voting statistics from the 2004 election show MSU’s campus town of East Lansing as one of only two cities in Michigan that voted for equal gay rights on marriage. Despite this seeming embrace of acceptance, the history of both the city and university reflects a continuing struggle of the kind of repression Todd and I still face on an almost daily basis.

During the 1990s, when Todd and I were mere 8-year-olds, not even thinking about boys or girls, MSU assembled a task force on LGBT issues. Between 1990 and 1992, the task force dug through old campus newspapers and personal accounts — a total of 100 people, middle-class folk, gay, straight, old, young, faculty, staff, and students, offering their private thoughts and experiences — to unearth a history of what happened on MSU’s large midwestern university from the ‘30s through the present.

In the 1930s, MSU’s campus (then Michigan State College) had nothinglike the amount of tolerance it has today. In fact, if you were gay, you guarded your secret and kept a watchful eye out for any undercover surveillance. According to the task force report, the closest establishment to same-sex bars back then was the Black and Tan Club on Shiawassee Street in Lansing. The B and T Club was not a gay institution, but something equally risky — a place where black and white people danced together, and where, emboldened by this barrier crossing, the occasional homosexual person would show up. The gay revolution, however, didn’t begin to appear until the 1950s.

In that era, despite the hatred toward gays, there was still hope for a place of their own, the task force reports, and two bars opened thei doors to the homosexual public. The Quick Bar, and later, Woodward, gave small groups a place to go, and more began to follow. These bars not only gave gay people a place to relax, and socialize, such as Spiral — the hippest gay bar in downtown Lansing — does for Todd and me, but they also allowed LGBT folk to open up and meet other people like themselves. The task force reports that after the bars opened, groups of people would meet in their homes and have private parties, expanding their gay networks.

Coming to terms

My own upbringing mirrors the slow adjustment of MSU and the state of Michigan because it has taken me years to accept my own sexuality.

I was born in Flint, Michigan, notoriously known for its run-down General Motors plant, Michael Moore, and the forever deteriorating image of the city since the car factory shut down. My parents, both GM employees, relocated when I was in fourth grade from Burton, Flint’s nastier sister city, to Grand Blanc, a ritzy, well-off city that’s known for the annual Buick Open — a golf extravaganza Tiger Woods and other pros play in. I went to Goodrich Area Schools, situated a few miles up the road from my home, in the middle of acres of corn fields. Corn isn’t really exciting, and neither was Goodrich.

It’s been hard for me to open up and be myself. In sixth grade I already knew something was “wrong” with me when I fell asleep dreaming of a female criminal whom I, the undercover agent, was supposed to hunt down and cuff. I found her in a corner in an abandoned warehouse, and all I could fixate on in my dream was her breasts. At the time, I didn’t really know what homosexuality was, so I told myself it would be alright. I would be alright.

Right I was about my sexuality; wrong I was about it being alright. After dating a dopey gothic boy almost my entire my freshman year of high school, I started to date a girl. I met her in the hallway one afternoon after lunch period. I had heard rumors she was gay. She was a year younger than me, and even our first conversation flooded with flirting. She told me, “The rumor’s true,” and walked away, telling me she’d see me later.

We kept our relationship secret from most of the school, but everyone pretty much knew we were dating. When you live amongst the corn, the corn has ears, and those ears pick up small bits of talk all day long. We never faced any hatred, however; Goodrich was pretty laid back. But, on the other hand, I felt I was separating myself from my family. I had to come clean with my mom, my confidant, so I wrote a page-long letter dishing everything to her — my relationship, my feelings for women, my fear she would reject me. I left it on the table, and slept between bumps and knocks in the house, constantly waking with the lump in my throat suggesting that my mother was at my door.

The next morning was the worst of my life. My mom cried, told me it would be alright, told me not to lie to her anymore, and told me a lot of other do’s and don’ts. She said we would get through the awkward stage, as long as I didn’t lie to her about dating people.

The last part didn’t take. I continued to lie to everyone at home, then in college until my sophomore year. But that was before I met Emily.

Emily came along months after Todd. In fact, when I first laid eyes on Emily, it was Todd who listened to my lovelorn descriptions of her. He was my personal relationship advisor, giving me the nod or shake of the head when cute or interesting ladies walked down the street. In my eyes, Emily was perfect — quiet, reserved, fashionable, and edgy. There was an aspect to Emily that was so mysterious, I couldn’t help but want more.

After Emily’s roommate, Katie, and I paired up for a project in history class, my interest was piqued. Katie constantly bitched and moaned about how irresponsible Emily unplugged her alarm clock at least once a week. I laughed and wondered how someone could deal with such a jerk, but after Emily and I started going out, I didn’t mind the alarm clock being unplugged every now and then.

Throughout all of this, Todd was by my side, slipping homemade cards featuring dancing butterflies under my door whenever love’s roller coaster took a dip.

It was during that freshman year when, down in the dumps and seeking an escape from MSU life, Todd and I headed out to the only 18-and-over joint that was also gay-friendly — Spiral Video and Dance Bar. We ventured out alone, and ended up at a table with another couple. They bought us tequila shots for the rest of the night and we danced in a foursome on the sweat-soaked floor. After being driven home drunk by the even drunker

couple, Todd and I declared Spiral would be our new home away from the dorms, and that’s where we would spend our weekends, dancing the night away.

Stolen pride

Emily, Todd, and Spiral were part of my coming out. Life on campus also allowed me to grasp my gay roots. Everyone was so liberal and open; there were signs hanging in dorms for meetings with other gay students, and the people I came out to never dropped their jaws in disbelief. I am so thankful I wasn’t on MSU’s campus during the 1960s, when life wasn’t a root beer float with whipped topping.

Fortysomeodd years ago was the breaking point for both homosexual people and campus administrators. Before then, there was no reference to homosexuality or gay arrests in any police report, on or off campus. But in the decade famous for its massive protests of the Vietnam War, it was evident gay people were gaining a voice and the police were clearly on guard. In 1960, “homosexual activity” was added as a category for complaints through MSU’s Department of Public Safety. Within a year after the category was added, nearly a dozen complaints and six arrests were made for what police referred to as“people engaged in or attempting to procure homosexual activity.”

As arrests continued through 1962-1963, campus landmarks were renovated in hopes of altering “physical arrangements to discourage the recruiting of homosexuals.” The campus student union had its basement men’s room remodeled in hopes that gay people would stop meeting there. Yet the handfuls of hidden spots on campus where heterosexual people, such as beneath the Belmont Tower, met remained intact.

In 1969, after police raided the Stonewall Inn — a dark and dingy predominantly gay club in Greenwich Village — campus groups become electrified by the resistance put up in New York. They admired their gay brothers and sisters who resisted the police force, and they too wanted to take a step into the accepting future. It was then, after Stonewall, that a weekly discussion group for homosexuals was formed off-campus, and MSU became one of the few universities across the country to have a gay organization.

Another positive step toward acceptance happened when the Gay Liberation Movement was registered as an on-campus student organization on April 27, 1970, and following it, the MSU Radicalesbians. Not far behind was a human sexuality course, taught by Eleanor Morrison, which focused on the components of sexual orientation and had assigned readings by lesbian and gay authors. MSU was becoming more accepting.

But progress for gay people is usually followed by repression. On March 4, 1972, the Michigan Gay Confederation established and planned the first Gay Pride Week on MSU’s campus. In June 1972, the start of what was to be Gay Pride Week provoked the first confrontation between MSU administrators and the Gay Liberation Movement.

Jack Breslin, MSU’s Executive Vice President, denied the organization permission to hang a banner at one of MSU’s campus entrances.

Complaints were filed with the MSU Antidiscrimination Judicial Board on the basis of sexual discrimination. In lieu of the complaints, Breslin responded, “I honestly believe that it is well within the powers of the MSU Board of Trustees to refuse permission for activities promoting lifestyles which are clearly at odds with the general atmosphere of the university.”

Arguments ensued regarding whether homosexuals should even be allowed to file complaints with the Judicial Board, and eventually the Board of Trustees decided complaints could only be filed by gay people if they were related to job discrimination. Through all of this, the banner was still not flying, and the first Gay Pride Week had come and gone.

Finally, in 1973, on-campus gay groups were allowed their banner recognizing Gay Pride Week. Kind of. Before the week began, administrators announced that the poles were going to be removed for “maintenance reasons,” the banner’s ropes were cut, and the landmark vanished from sight.

Downward spiral

Todd and I used to joke during our freshman year that if we didn’t find partners, we’d settle down together, get married, and fake the rest of our lives. If we were straight, we’d be able to do whatever we wanted. Todd and I could kiss by campus landmarks and no one would think twice about it. We could go into lingerie stores and buy handfuls of bras and underwear for me, and the clerk wouldn’t hesitate to serve us. If waiters asked the question, “One check, or two?” and we replied, “One,” they wouldn’t smile sly grins and think to themselves, “I wonder if I can get both of them home tonight …” It happens to Emily and me all the time.

Usually, though, we can find safety from the wandering eyes and glaring stares when we go to gay bars. So, a few weekends ago, Todd, Emily, and I went to our old favorite, Spiral. We still go to Spiral after all these years because it has a New York feel in our very non-New York town. When walking in, the industrial feel of the nightclub is punched out in tall, metal chairs adorned with red velvet on the cushions. Candles burn, little lounges are filled with red velvet couches, the bathrooms have red velvet curtains instead of doors, and the overall feel is pristine and modern.

Emily and I were sitting, sipping our glass-bottled beers, when a man approached Emily to tell her she was beautiful. She smiled, thanked him and proceeded to ignore his presence. You get these creeps all the time at the gay bar — men out to woo a lesbian.

The man finagled his way into a seat next to Emily and continued to tell her she was gorgeous. I tried shooting him a no-trespassing look, letting him know I was the only one who was going to eat sushi that night. There’s nothing more frustrating than a straight person trying to convert your lover. Instead of throwing a big fuss, though, I just pulled Emily onto the dance floor.

All of a sudden, I see him again. He’s talking to Emily, and I can tell by her uneven smile that he’s still telling her she’s beautiful, still trying to get into her pants, still being a pig.

“We’ve been together for two years,” I hear. “I’m sorry, I’m not interested.”

Emily’s smile is waning and my patience is growing as thin as the air on the packed dance floor. My friends, who can feel my tension, form a human wall between Emily and the man. It’s literally me, Emily, two friends, and the man trying to squirm his way into our dance circle. We’re still trying to keep our cool, dancing, but the man persists. He gives my friends the finger, picks my girlfriend up, raises her to the ceiling, and puts his face in her crotch.

I don’t remember if I shoved the guy, grabbed Emily, or if he just let her go, but we spilled off the dance floor in one fluid motion. I found Todd and his date and explained the whole situation; disbelieving, Todd and his date gallantly offered to kick the guy’s ass. I couldn’t stop thinking if Emily and I had been a straight couple, the man wouldn’t have had the nerve to so aggressively try and break us apart. I was surprised by the depth of my own anger. I hated this interloper and, if I didn’t want to be banned from my favorite gay bar, might even have entertained the idea of macing the bastard’s eyeballs.

And this is still the life we live, every day. We’re constantly battling to open ourselves up, dealing with a society that still wouldn’t mind repressing us and all the while politely doesn’t understand us. MSU has given Todd and me the chance to become who we are, and become more assertive along the way. We might not be 100 percent open, but we’re getting there.

Without the help of MSU’s understanding student population, or the Pride festivals Todd and I still venture to today, I might still be resting in the proverbial gay closet — a place where no LGBT person ever likes to hang out. And those pride festivals Todd and I used to feel weird about? We go to them every year, in as many cities as we can. Last year, Todd spent the night at my apartment, and when we woke up, the park across the river was filled with white trailers, rainbow flags, and tons of people. People just like us. We got dressed and walked over together.

This time, we stood by the fence where the protestors were and laughed at them. We ate elephant ears and strolled around the various vendors. We were happy children were there, because after all, when I have kids, I’m going to want them to see all sides of life. But most important, and closest to my heart, my girlfriend broke her pact of never showing public displays of affection and held my hand. And for the first time ever, I finally felt complete.

STORY INDEX

TOPICS > RESOURCES

Michigan State University’s LGBT website

Resources, event listings and services for students, staff and others.

URL: http://lbgtc.msu.edu/

ORGANIZATIONS >

Triangle Foundation

One of Michigan’s organizations serving the LGBT and allied communities.

URL: http://www.tri.org/

In The Fray Contributor

Dear Reader,

In The Fray is a nonprofit staffed by volunteers. If you liked this piece, could you

please donate $10? If you want to help, you can also: