A truck had dropped me off at a crossroads. But instead of driving away, the well-meaning driver was still trying to tell me something. Probably, “No cars are coming. You’re in the middle of nowhere. Are you crazy? What are you doing, little lady?”

I got the gist, even though I didn’t speak Spanish. I started walking, and as the distance between us grew, I could hear him yelling that maybe this was a bad idea, and he motioned for me to get back into the truck. He honked again.

But I kept on walking. No time for debate.

I passed a man wearing a suit and a felt hat, who was also headed for San Diego de los Banos, a town known for its thermal baths. He was just standing there, waiting in the middle of nowhere, as if it were a bus stop. But there was no bus stop. No car or another person in sight.

Perhaps he is still waiting there.

The man said that San Diego de los Banos was a long way off — 15 kilometers at least. But rather than join him, standing in the countryside, with the chance that a car may never show up, I decided that if I walked fast enough, perhaps I could still reach the town by nightfall.

It was now 3:30 p.m. The sky was overcast. About three more hours of sunlight left. Remembering the distance of bygone high school cross-country races, I calculated that 3.1 miles equaled five kilometers. If I can walk three miles per hour, surely I can reach town by dark, I thought. It is doable.

So I began walking. And I walked and walked.

And not a single car came by.

The road through the countryside rose and fell, and soon, the flatness of the land gave way to a forest of pines and cedars. Not far from here, Che Guevara had moved his headquarters into a cave during the Cuban Missile Crisis. It was just me and this forest, and if I shouted, I’d spook myself.

Suddenly, two men emerged from nowhere, walking next to their bikes. Perhaps there was a house tucked away in the forest that I couldn’t see. I began to walk a little faster, but the two men were gaining on me.

Why are they walking next to their bikes? I asked myself.

My duffel was heavy, and I tried to pick up the pace, but they were getting closer.

I could totally be raped and robbed right now, I thought, clenching my teeth.

I stopped and let them overtake me. A teenager with his father on a bicycle ride, it appeared. They happened to be walking next to their bikes because the hill was on an incline.

“Hola,” they said, after I gamely raised my hand and said, “hi.” I knew I was safe after I asked them how far San Diego de los Banos was, and the man replied with a wave of his hand into the distance, “twelve kilometers. It’s far away.” I reassured him that I was hoping to flag a car that came this way. He nodded, and they soon passed me.

I walked a few more kilometers when I saw two other men approaching from behind — again walking with their bikes.

There is nobody around, so I am really at their mercy here, I began to think. Suppose I get killed in this forest. The Cuban police might take a week to identify my rotting body from my passport photo. My imagination was getting the better of me again; I began to wonder how much media coverage the story would get at home.

And then, the men were next to me. One of them offered to put my bag on his bike. I said no, that I can carry it myself. Now there is a ploy, I thought. Put the tourist’s bag on the bike and ride off.

It was not until the younger of the two men smiled sympathetically and said something about confianza that I softened. I said “si,” and put my duffel on his bike. I recognized the word from the French confiance, which means “trust.”

And so began our 12-kilometer ride to San Diego de los Banos, where the two men lived. The sun emerged, and the skies then revealed the depth of their blue heights, with wispy clouds soaring high above. When we would reach the summit of a hill, I would sit atop the horizontal bar of the bike, “sidesaddle,” in front of the younger man, and hold onto the inner handle bar while he, wearing my backpack, would steer us both downhill, with the older man following close behind.

We’d breeze past palm trees and lush vegetation, the young man applying the brakes generously and carefully avoiding the road’s potholes, until the hill petered out. Then the three of us would hop off the bikes and walk them up to the next summit, get back on, and ride downhill again.

A strange grunting noise seemed to follow us each time we stopped. And then came a long squeal.

Poking out of the slits of two sacks tied onto each bike were two snouts, each sniffing the air as if to figure out what was going on. We were biking with a couple of hogs.

“Musica,” joked the younger man as we navigated down yet another hill.

As we approached town, we passed people who looked up and stared. Sometimes, I heard laughs and “Chiiiiina.”

I am American, but I let people think I was from China during this trip to see Cuba on my own. “Chairman Mao!” some would offer generously in a eureka moment of finding common ground. “Lejos,” or “far,” people would say, in remarking how long my plane trip must have been from Asia.

I often got those comments while walking — or waiting for transport.

This is a country where you often have to stick your thumb out to get somewhere, especially when off the beaten track, because of a shortage of buses. No hitch aboard a tractor, truck, or even motorcycle sidecar prepared me, however, for the possibility of catching a ride aboard somebody’s bicycle.

When the younger man had first motioned for me to jump on his bike, I balked. How did he want me to sit, I wondered. Did he want me to straddle it?

“You’re from China,” he said, laughing. “You don’t know how?” He then stuck out his butt to demonstrate that the best way was to sit sideways.

I do know this. I would probably still be walking in the dark in that uninhabited forest, were it not for those two men. Not once did a car pass along the road that entire time.

We made it to town just before nightfall.

- Follow us on Twitter: @inthefray

- Comment on stories or like us on Facebook

- Subscribe to our free email newsletter

- Send us your writing, photography, or artwork

- Republish our Creative Commons-licensed content

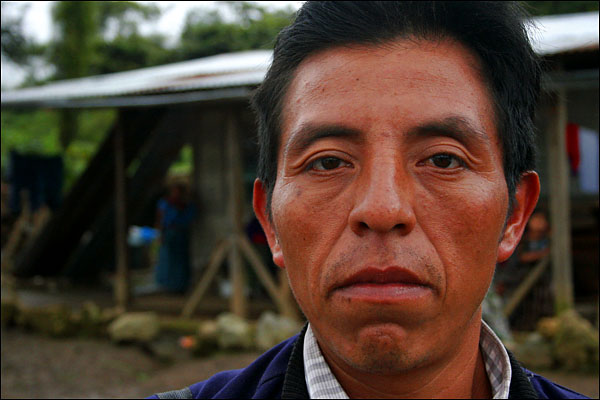

Post-war reparations in Guatemala.

Post-war reparations in Guatemala.