What is life like in Gaza, more than a year since Israel began its military assault there? I spoke to Mariam Salah, a twenty-nine-year-old artist and teacher who lives there, for a personal perspective on the war. Salah has lost six family members and eight friends since Israeli forces swept into the Gaza Strip in response to a Hamas-led series of attacks on October 7, 2023. They are among the tens of thousands of Palestinians reported to have been killed during the ongoing conflict, which shows no sign of ending. An estimated 1.9 million out of Gaza’s 2.2 million residents have been displaced, while the fates of dozens of hostages taken by Hamas are still unknown.

When the Israeli military assault began, Salah was living in Gaza City. She and her family have been forced to flee their homes several times since then. Currently, they are camping out in Khan Yunis in the south—“seeking shelter amid the rubble we’re surrounded by,” as she puts it.

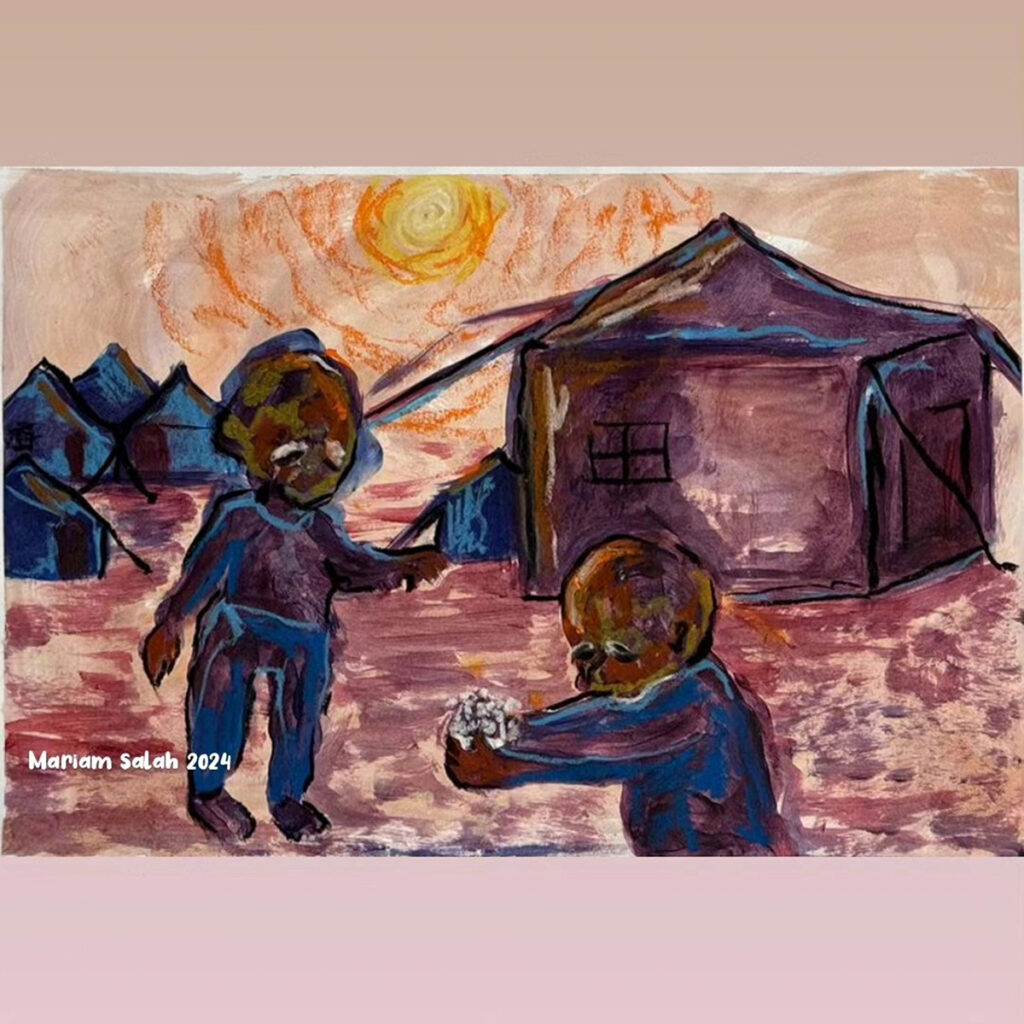

A painter and sculptor, Salah had her work exhibited in galleries throughout Palestine before the war. She designed costumes, masks, and puppets for a local company called Theater Days. Salah also worked with children as an art teacher and art facilitator at schools run by the United Nations Relief and Works Agency (UNRWA), the main U.N. aid group in Gaza. She graduated in 2017 with a bachelor’s degree in art education from Palestine’s Al-Aqsa University—since flattened by Israeli strikes. “Every single place I used to study or work has been turned into rubble.”

Where exactly were you living in the Gaza Strip before Israel attacked?

I was living in northern Gaza—specifically, in the capital, Gaza City. There were eight refugee camps spread throughout the Gaza Strip, and I lived in the Beach Camp, which is very close to the Mediterranean Sea. It’s since been decimated—completely reduced to rubble.

Like so many people, my family and I didn’t want to leave our home at first. We took shelter in a nearby UNRWA school. We were confident we’d be protected, as we thought the institution’s role of preserving human rights would be upheld. We were under the impression the occupation forces wouldn’t have the audacity to blow it up with so many people crammed in and seeking shelter.

On one particularly harrowing day, the building began to shake from the force of the shelling. We couldn’t sleep. Early in the morning, a young man was killed at the front entrance of the school.

We decided to flee. We didn’t take any of our belongings, only the clothes we were wearing.

There was an impending sense of doom, and I was reminded of the movie War of the Worlds. We traveled several kilometers on foot to seek safety in the southern city of Rafah. Of course, it’s since been destroyed. We have been displaced four times since the military assault began.

I understand one of your nephews was killed.

His name was Bashar. He was eighteen years old and my eldest nephew. On July 22, a missile struck the home in which we had been seeking refuge, and he was martyred. My nephew, Hassan, who was ten months old, was seriously injured in the head, but thankfully, he survived. My two brothers-in-laws were also seriously injured, but they’ve also been making progress with their recovery.

Bashar was really dear to me. I considered him a son, as I’m still single. I’d describe him as being kind and compassionate. He never wanted to hurt anyone, and he always looked after everyone else’s needs. Following his death, it became apparent just how much he was loved.

We used to have a skincare ritual—it was something we’d do together periodically, just to lift our spirits a bit. He wanted me to help him look and feel better, as we’ve all been so weary. One week before he was killed, during our ritual, we had a conversation about the fragility of existence—how our lives hang in the balance between life and death. I held him close.

A missile would eventually destroy his face, shattering it into pieces. Now that he’s in heaven, my hope is that his face is even more beautiful than it was here on earth.

I thank God we buried him and that we actually know where exactly his grave is. The truth is, so many people have been buried, and their families have absolutely no idea where they are. My maternal grandmother is one example. She was killed on the day the despicable Israeli Army entered Khan Yunis. There was intense bombing and shelling.

She was buried, along with others, in a mass grave in the hospital’s courtyard. We neither have a designated place to mourn, nor to grieve. My mother was deprived of saying goodbye to her, and so were the rest of my aunts. I haven’t fully recovered from all of this.

How have you gotten food, water, and medical care?

During the first month of the military assault, almost everything was available. We’d buy and store canned food to eat. Once we were in Rafah, we found a lot of expired products in the markets. We’d only buy vegetables once a week, as they were very expensive.

Every two months, we receive a box of humanitarian aid that reaches schools or other distribution points. We used to buy food with the money we had saved prior to the military assault, but it’s simply not enough to cover the exorbitant cost of everything, thanks to the damned war merchants.

In a Facebook post, you discussed the challenges of cooking over a fire.

We have to light a fire every day, because there aren’t any alternatives. We’re all forced to search for paper, cartons, and wood to start a fire. It’s also difficult, because everyone else is trying desperately to find the necessary material. With children being out of school, their old notebooks have been used.

The mothers who are constantly cooking over fire have been experiencing respiratory problems. And to be honest, food cooked over a fire is hardly appetizing to me. But we all want to live, so we carry on.

You mentioned how your flip-flops came apart and how difficult it’s been to get a new pair.

The journey of my flip-flops may be comical, but since my fourth displacement, I’ve lost four pairs. I had to resort to fashioning a pair on my own. I used cardboard and the caulking that’s used to fill holes in windows and doors.

I also had a pair of shoes that were covered in dirt, so I painted them in an attempt to refurbish them. I wanted to give them a shine akin to the shine of a new pair, but they quickly became dirty due to the sewage, dirty water, sand, and rubble in our streets.

Please tell me a little about the artwork you’ve been able to create.

I’ve lost all my paintings, sketches, materials, and supplies, and all my books and research on art. I’ve managed to express myself in some way on paper, but I don’t consider what I’ve produced to be artwork. What I’ve drawn simply represents a release of myself. There’s no time for art. I’m now saving my life and the life of my family. My life is now more important than art.

Your artwork was exhibited at a gallery in Bethlehem a few years ago. Can you tell me about this exhibition?

To be honest with you, ever since the genocide started, I’ve had trouble remembering specific details about my past activities. I don’t recall what was displayed in Bethlehem. It might’ve been a painting about the right of women to live freely, or the right of children to live in dignity. I really don’t know. I just remember I had sent a few of my artistic works there.

In any case, it really doesn’t matter. The crux of the matter is the reality of our lives under a brutal, decades-long military occupation and apartheid.

What’s the role of art under the circumstances we’re currently enduring? It has neither allowed us to live, nor has it allowed for a ceasefire to come into effect. I’d like to say that art is of no use amidst mass displacement, starvation, and killing. The artist must come to acknowledge that neither the paper drawn on, nor the quill used for writing, can compare to the deadly power of a weapon on a battlefield. Unfortunately, I don’t have any military training, so I’m of no use, whether as a fighter or as an artist.

Do you have any wishes or dreams for the future?

I’d like to make a wish, but I know it won’t come true: I wish that all the people who were killed were alive. I wish that life could return to what it was like before. But it’s too late. Now, I only wish for the genocide to end. I also wish for Palestine to be liberated and rebuilt.

The Palestinian cause is inherited from one generation to another. The misery will not end until the aggression and injustice end. This will not end until those who support Israel wake up. And if they don’t wake up now, they may regret it in the afterlife.

Is there anything or anyone giving you strength or support to endure?

No, not at all. Everyone’s weak and exhausted. All of us have been deeply affected by this genocide. No one has been left untouched. To some extent, the strength within me is due to my faith in God. Right now, my goal is to support my family and to have them cling onto me amid a sea of blood.

It’s been impossible to heal. However, there’s something in my heart that reassures me that I’ll be reunited with Bashar in another world. I often look at the mobile phone charger he gave me and think it’s only a matter of time before I see him again.

This interview has been condensed and edited for clarity.

Ayah Victoria McKhail Ayah Victoria McKhail is a writer based in Toronto, Canada.

- Follow us on Twitter: @inthefray

- Comment on stories or like us on Facebook

- Subscribe to our free email newsletter

- Send us your writing, photography, or artwork

- Republish our Creative Commons-licensed content