It was fall in Mongolia, and the dusk falling round the State Department Store, the central meeting place in the capital city of Ulaanbaatar, made it hard to see anyone’s face — not that I knew what the man I was supposed to meet looked like. I had just arrived for the year to work with writers, and my desire to see the creation of a Mongolian branch of International PEN was shared by Dugar, an Inner Mongolian writer living in New York City.

The two of us had never met. Dugar got my name from the Freedom to Write and international programs director Larry Siems at PEN in New York when Dugar called to ask about the possibility of establishing a Mongolian PEN Center. Larry happened to know I was in Mongolia, trying to make that very idea a reality. Dugar emailed me and asked me to look up an Inner Mongolian writer living in exile from China, in Ulaanbaatar: Mr. Tumen Ulzii Bayunmend. I thought the two were friends, but later I’d find out that Dugar knew of Tumen Ulzii because Tumen Ulzii was a prominent essayist — he wrote about the Chinese government’s actions toward Inner Mongolians — and a leading figure in the People’s Party of Inner Mongolia.

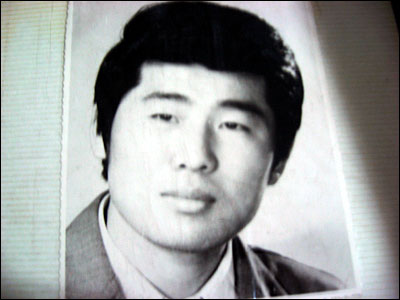

The man I met in front of the State Department Store didn’t look like a refugee, which goes to show how many assumptions I had. Tumen Ulzii has an open, smooth, and youthful face. We wove through the crowds of young people hanging out in front of the State Department Store, and made our way onto Peace Street and into a melee of knockoff sunglasses stands and Korean restaurants. That night at Broadway Pizza, with only the most basic Mongolian words under my belt and about ten English words under his, Tumen Ulzii and I relied almost entirely on pens, paper, an electronic dictionary, beer, and universal gestures for conversation.

Tumen Ulzii is keen and quick. He told me about himself first, then about his move to China, his wife and daughter who are still there, and the books he wrote about race and politics that brought Inner Mongolian fans in from the countryside just to meet him. These same books precipitated a ban on his writing in China and the police raids on his office and home after he left China for Mongolia in 2005. The reason so many Inner Mongolians speak out against the Chinese government — or would like to — is the long history of oppression like that suffered by Tibetans; the effort for cultural preservation, expression, and autonomy among ethnic minorities has often led to clashes with the Chinese government, and Tumen Ulzii’s story is just one of many.

Differences between Inner and Outer Mongolia

The country of Mongolia is the territory once referred to as Outer Mongolia, and the territory of Inner Mongolia lies in China. The size of the difference between Inner and Outer Mongolians depends on who you ask.

Inner Mongolians see themselves as part of a larger Mongolia, but this view is not shared by the Outer Mongolian public, and anyone from any part of China is at risk here due to a sentiment proven by the “fucking Chinese go home” graffiti outside my apartment, and the recently acquired black eye of my young Chinese friend Li, who is here to study. Ulaanbaatar is a small city, and Tumen Ulzii, audibly from a Chinese region, does not feel safe.

Language differences between the two are also apparent; Tumen Ulzii speaks differently from Outer Mongolians. Inner Mongolian dialect has a “j” sound where Outer has a “ts” sound, and the pronouns are a bit different. Inner Mongolians still use the traditional Mongolian vertical script for everything from school notes to street signs. Tumen Ulzii, also fluent in Japanese and Chinese, is confounded by the Cyrillic type used here in (Outer) Mongolia. My Mongolian teacher, Tuya, is the only younger Mongolian I’ve met who knows traditional Mongolian script well. Though the Cyrillic type was instituted here in (Outer) Mongolia only in 1944, it has taken deep hold. The pages of Tumen’s notebook, however, are covered in the rows of lacy black script whose vertical nature, Mongolians say, makes you nod yes to the world as you read instead of shaking your head no.

Refugee situations are not easy

On a much colder and clearer day in January, Tumen Ulzii and I walked the five minutes from my apartment to the Mongolian branch of the United Nations (U.N.). Uniformed men in their early 20s guarded the compound. Even without my passport — I had left it on my dresser to remind myself to get more pages at the American embassy — they let me in. Tumen Ulzii and I crossed an eerily quiet parking lot filled with white vans to a pink, Soviet-style building, where the receptionist asked about my lack of documentation. We walked into the U.N. High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) office, whose walls were home to UNICEF posters and the air smelled of coffee, and I asked one large Mongolian man, Mr. Och, what the holdup was on Tumen Ulzii’s refugee status.

Refugee situations are never easy, and this was no exception. Mongolia does not have an official UNHCR branch, only a liaison office, so the decision to grant Tumen Ulzii refugee status had to come from the nearest branch, which happened to be in … Beijing. Mongolia also has no provisions for asylum seekers in its law, so as long as Tumen Ulzii remained one, he was at risk of deportation and then punishment at the hands of the very government who had its police officers storm his house and strip-search his wife.

Tumen Ulzii has not been the only one. His friend Soyolt, another Inner Mongolian dissident, was arrested on January 7, 2008, upon touchdown in Beijing on a business trip. Soyolt was in the impenetrable world of arbitrary detention without charge or trial somewhere in China for the next six months while his wife and three children remained powerless here in Ulaanbaatar. He was allowed one phone call back in January, and he reported that Chinese officials had told him that if he made a fuss or alerted any foreign media, things would get worse.

The imminent Olympic Games in Beijing seems to be both a blessing and a curse for Chinese dissidents: Attempts by the Chinese government to silence them during the buildup to the Olympics has increased, but for the lucky dissidents who get noticed by the international community — a community currently paying extra-close attention to China and its human rights record — the imminence of the Olympic Games can help their cause.

Mr. Och at UNHCR told me to secure a letter of support for Tumen Ulzii from Freedom to Write at PEN in New York, and that a decision should come in the next week — something he would tell me for three months. Afterward, Tumen Ulzii and I went to get a beer. Tumen loves that I like beer. It was midafternoon, but around here people drink beer at lunch — at least the demographic I work with (read: middle-aged male writers).

“Bayarlalaa, minii okhin,” he says. Thank you, my daughter. “Sain okhin,” he says. Good girl.

Visiting with friends and family

Tumen Ulzii is extremely intelligent, but there are some things he says that boggle me. He can understand lesbianism, but not male homosexuality, and he wants to know why it exists, and how the sex happens. He thinks Hitler’s fine, since he wasn’t as bad as Stalin. He likes President Bush, purely because Bush is the president of the United States.

He does have a few good friends here. Uchida is a gentle Japanese man and a great friend of Tumen Ulzii’s. I met with both men several times at the pub around the corner from where I live. Uchida, who studied in Inner Mongolia, showed me cell phone pictures of his four-month-old baby — the baby and her mother live in Japan. When I wrote up a bio of Tumen Ulzii to forward to PEN’s Freedom to Write program, the men checked it over, with Uchida translating, while I dug into fried meat and rice. Though they are both in their 40s, they looked and sounded like school buddies hunched over a cheat sheet, casual and affectionate. Afterward, I told them I needed to go and clean my floor. They told me they would like me to stay and drink beer with them instead.

“Do tomorrow,” Uchida said.

“What do tomorrow?” I asked, and at the same time, one man mopped with an invisible mop and the other swept with an invisible broom.

Tumen Ulzii had Tuya and me over for a real Inner Mongolian dinner at his modest and bare but immaculately clean apartment, which was on the worst side of town, near the black market. To begin, he gave me a bowl of milky tea with some kind of grain cereal at the bottom. This was suutetsai, a dish nomadic Mongolians have at every meal, which consists of green tea, milk, and salt. He then surprised me by thumbing off pieces of meat from the boiled sheep leg on the table and dropping them one by one into the bowl, something he kept doing throughout the meal. It wasn’t half bad, once I expanded my mindset to one that included garnishing something like crunchy Cream of Wheat with mutton.

The second time I visited Tumen Ulzii at his home, I came by myself during the February holiday of tsagaan sar (“white moon” or “white month”). He had invited me weeks beforehand to be present on the first day of his wife and daughter’s 10-day visit. He and his daughter Ona, a delicate university student speaking very good English, picked me up in a taxi (which in Ulaanbaatar is usually a beat-up stick-shift car driven by a regular guy who could use a thousand or two tugriks). We stopped for groceries; he wanted to get beer for me and he wanted Ona to have one too, like me, something which she does not usually drink and which I tried to stop drinking.

On the way up the stairs, Tumen Ulzii took us one floor too far, then couldn’t figure out why his key didn’t work, and Ona gave him grief for it in universally understandable tones. That night Tumen Ulzii came alive, bickering with Ona, their voices singing in Mongolian and Chinese across the kitchen. Tumen Ulzii is immensely proud of his daughter; she tested into the top 10 percent of university students in China. I took videos of them singing traditional Inner Mongolian songs and smiled at his wife, a quiet geography teacher a few years older than Tumen Ulzii. I felt guilty for knowing what was done to her at the border the last time she visited her husband, trying not to imagine it now that I had seen her tired face.

An official refugee, at last

Spring 2008 … not spring by the standards of my home in California — it snowed last week — but sunny enough for sunglasses as I waited for Tumen Ulzii in front of the State Department Store. He approached in a long black coat and shades that made him look like a spy in a big-budget movie. He smelled my cheeks, the customary Mongolian greeting, and as we walked away from the throngs, he said, “Min! United Nations, okay!” and put his thumb up. I whooped and called Och, who confirmed the news. Tumen Ulzii had become an official refugee, eligible for resettlement. The letter Larry Siems at PEN Freedom to Write in New York sent expressing concern about Tumen Ulzii had been crucial to the decision.

To celebrate, Tumen Ulzii took me to a Korean restaurant. He laid several strips of fatty meat (Mongolian meat always comes this way) on the griddle set up at our table. My Mongolian was better than it was six months ago when we first met, but we still did a fair amount of the gesturing. He raised his beer, pronouncing me an Inner Mongolian daughter.

Resettlement, yes. But where?

Uchida comes and goes from Japan every couple of months, always with new pictures of his child to show Tumen Ulzii. Their friendship thrives despite distance, so when Tumen Ulzii resettles, there is no doubt they’ll remain in touch. Meanwhile, Tumen Ulzii’s keen to know which presidential candidates are leading in my country, and overjoyed that Obama is dark-skinned. He now wonders where I think the best place to resettle would be. America? He mimes an injection into his arm, then, reading from a book, puts his arm high into the air: “Hospitals and university fees are high in America.”

Resettlement can be a long and difficult process. Canada or Europe, we hope. He is very concerned that Ona go to a good university. He loves dogs, but can’t have one here — somewhere he can have a dog. Tumen Ulzii insists that when I visit Hohhot next month I stay with his wife.

“Sain okhin,” he says, kissing the top of my head. Good girl.

- Follow us on Twitter: @inthefray

- Comment on stories or like us on Facebook

- Subscribe to our free email newsletter

- Send us your writing, photography, or artwork

- Republish our Creative Commons-licensed content