In Riyadh for a business trip, I found myself with a couple of hours to kill. I decided to wander around Al Olaya, the Saudi capital’s commercial core and upscale shopping district. In a gleaming shopping mall surrounding my hotel, I saw familiar brand logos on either side, a glitzy array of high-end storefronts much like those you’d find in any major Western city—except for the stylized Arabic lettering. Eventually, I came across the garish window display of a Victoria’s Secret. There I stopped, amazed.

![]() I had actually lived in Riyadh two decades earlier, having come to Saudi Arabia to work as a physician. At the time, there were no Victoria’s Secret stores to be found. The company’s website was even blocked by the religious authorities. Women could buy lingerie, but they had to do so in a general store—and all the shops back then were staffed exclusively by male attendants (women were not allowed to work in most public spaces). All these prohibitions had made shopping for intimate apparel a singularly humiliating experience.

I had actually lived in Riyadh two decades earlier, having come to Saudi Arabia to work as a physician. At the time, there were no Victoria’s Secret stores to be found. The company’s website was even blocked by the religious authorities. Women could buy lingerie, but they had to do so in a general store—and all the shops back then were staffed exclusively by male attendants (women were not allowed to work in most public spaces). All these prohibitions had made shopping for intimate apparel a singularly humiliating experience.

So much had changed in Saudi Arabia, and it wasn’t just about the overt femininity of a lingerie store. I walked into another familiar Western store, a Louis Vuitton boutique. The fall collection was being displayed—luxury scarves, elegant handbags—much the same as it would be in New York City. The mannequins wore shorts and dresses with bare plastic legs. But what captured my attention were their heads—molded plastic, with detailed facial features. Two decades ago, that depiction of the female form was forbidden. The mannequins back then would have been headless.

I must have looked ever so slightly lunatic in that store, gawking at the mannequins. Soon enough, a store clerk approached me, and we began talking about my impressions of the new Saudi Arabia. A group of attendants—all of them, notably, women—began to gather, curious about my excited chatter. I explained to them that when I lived in Riyadh, the mall had a designated floor just for women, the only place in this mall where we were allowed to shop. Even having that women-only space had been an advance at the time; other malls would only let women shop during restricted hours when men would not be present.

As I told the women about their country’s recent past, I felt like a time traveler speaking of unimaginable sights. All the store clerks were young—not surprising in a country where two-thirds of the population is under thirty. While some of them wore headscarves, others did not. They seemed to find my enthusiasm infectious, and they asked many questions. We ended our impromptu chat with the conclusion that, yes, this was Islam: the freedom for a woman to choose how to observe, to choose how to be.

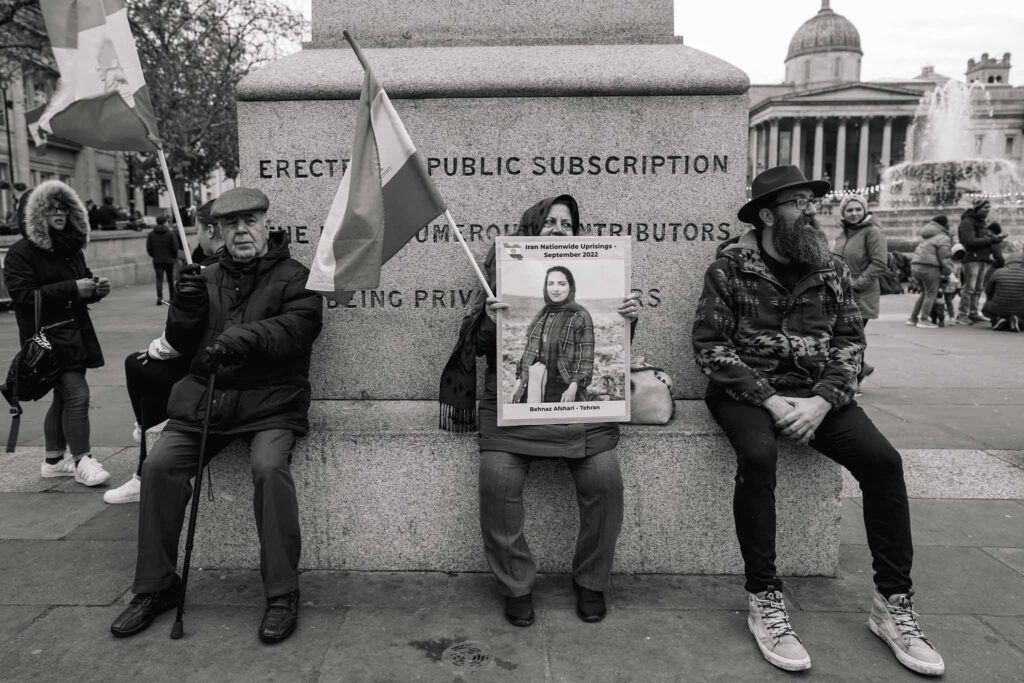

Since I’ve returned from my trip, I’ve thought often about how much Saudi Arabia has changed—and whether another Muslim country, Iran, might take a similar path. For several months beginning in September, Iran was paralyzed by massive protests unlike any the country had seen since the 1979 revolution. The spark of this explosive rage was the suspicious death of Mahsa Jina Amini, a twenty-two-year-old Kurdish Iranian woman who had been detained by police for “improperly” wearing her hijab.

As protesters flooded the streets of Tehran and other major cities, social media greatly amplified their voices. RILA Global Consulting tracked Arabic- and English-language tweets in response to Amini’s death across hashtags like #IranRevolution, #IranUprisings, and #MahsaAmini. It counted more than 204 million tweets (a quarter of them in English), almost three times as much as for any other protest last year. In the last quarter of 2022, tweets about Amini accounted for almost half of all posts globally. This flurry of activity on social media went well beyond posts about the street protests, with some young Iranians finding creative ways to publicly express their anger at the theocracy, such as through viral video clips showing them running up to clerics and knocking off their turbans.

Iran promptly tried—and failed—to block access to the Internet during the height of the demonstrations. It was far more successful in quelling dissent on the streets, the brutality of its repression hinting at just how threatened the Iranian state was by the unprecedented uprising. At first, the regime pulled back the morality police from the streets of Tehran, which at the time some commentators reported as a possible concession to the protestors. But the bloodshed only ramped up from there. Ultimately, hundreds died (including dozens of children) and thousands were injured.

The regime has itself admitted to detaining “tens of thousands,” and it executed at least four protesters after what human rights groups described as sham trials. Majidreza Rahnavard, a man in his early twenties accused of fatally stabbing two state militia members, received just one court hearing; in the courtroom, his left arm was wrapped in a plaster cast, raising suspicions he had been tortured. He was later hanged from a crane.

The viciousness of the state’s crackdown was not surprising. The demonstrations drew immediate comparisons to the Arab Spring, the wave of uprisings across the Middle East that unfolded after the self-immolation of a Tunisian fruit seller in 2010, ultimately leading to the dismantling of multiple governments. Through a combination of live ammunition, beatings, jailings, and executions, the Iranian regime stamped out the existential threat posed by the street protests.

Nevertheless, the public furor ignited by Amini’s death has raised serious questions about the future of Iran’s authoritarian regime. While there are no signs that the government will reverse any of its repressive policies anytime soon, there were no obvious signs either, back in 2001, that Saudi Arabia was on the path to major reforms in its treatment of women or in the dominance of its hardline religious establishment. But reform came. My recent travels to Saudi Arabia have made me wonder what lessons other Muslim societies anxious for change could draw from the kingdom’s progress over the years in expanding freedoms for its citizens—as much as that struggle still continues.

In 1999, I moved to Saudi Arabia somewhat impulsively. I had just finished my training in New York City as a critical-care physician, and my special immigration visa was about to expire. But I didn’t want to return to England, my country of birth, where I had grown up as the daughter of Muslim Pakistani immigrants. Working in the UK’s struggling National Health Service didn’t appeal to me. I wanted to relocate to a place in need of my skills as an American-trained physician specializing in a technologically advanced field of medicine.

With only three weeks left on my U.S. visa, I found a recruiter hiring for medical positions in the Middle East. I landed a job practicing intensive-care medicine at the Saudi Arabian National Guard Hospital in Riyadh. The paperwork went through quickly, and on Thanksgiving Day I found myself waking up in Riyadh.

The two years I spent in Saudi Arabia were filled with some of the most extraordinary experiences of my life. This is where I built the foundation of my later academic work and became an expert in “Hajj medicine,” developing clinical approaches to tend to the needs of the millions of people worshipping in Mecca during Islam’s annual pilgrimage. Yet my early life in Riyadh was dominated by tense encounters with fundamentalist Islam.

Being a Muslim woman myself, I had expected that the culture shock I would experience in an Islamic country like Saudi Arabia would be mild. At that time, though, the country was dominated by an ultraconservative Sunni Islamic movement that outsiders called Wahhabism, given its roots in the teachings of the eighteenth-century scholar Muhammad ibn Abd al-Wahhab. As they are in Iran today, women and girls in the Saudi Arabia of that time were infantilized by the reactionary and puritanical clerics the state had chosen to empower. Wherever women went, however educated they were, they faced restrictions in movement, dress, and action. Most obviously, they were compelled to wear veils in public and denied the right to drive. Even as a non-Saudi, I had to cover my hair in public with a hijab and wear a floor-length abaya (a long black cloak) over my clothing to hide my form, and I too was forbidden to drive.

When I lived there, women and girls in Saudi Arabia could not obtain or renew their passport without the approval of a male guardian—a husband, father, brother, or son. They could go on the Hajj pilgrimage to Mecca only with a designated male relative, and they needed written permission from their male guardian to travel abroad. My female colleague, a surgeon-in-training, regularly had to obtain such permission from her father to travel overseas to professional meetings in Canada and elsewhere.

During my time in Saudi Arabia, I remember being regularly followed by pairs of religious police, the mutaween, who would admonish me whenever my headscarf inadvertently slipped down. The mutaween would also intercede whenever they saw people of the opposite gender interacting. Mixed gatherings, even in professional settings, were the target of raids. It was unlawful to sit with an unrelated person of the opposite gender in any public space—whether a mall, restaurant, or coffeeshop—and couples who did so might be asked to present their marriage licenses. The religious police took this persecution to a truly ludicrous extent. They once accosted my friend Atef, an Egyptian doctor, when his wife laughed out loud at one of his jokes. After forcing the couple to verify they were married to one another, the officers chastised my friend for causing an unseemly scene.

This infantilization of women extended to basic decisions about their lives. Women could not initiate a divorce (even though Islam permits this), and the law automatically awarded custody to fathers for any children older than seven. As a physician trained in the West, I was shocked to find out that women could not give consent for medical procedures; only their male relations could. At my hospital in Riyadh, I remember once tending to a Saudi woman in critical condition. I was unable to turn to her or any other adult—including older female relatives—for approval to move forward with her care. Instead, her young son—probably eleven or twelve years old—was the only one with the legal authority to make decisions on behalf of his deathly ill mother. I’ve forgotten her specific condition after all these years, but I’ve never forgotten the frightened expression on that small boy’s face as I explained the surgery his mother needed.

The Saudi state’s repression also extended to non-Muslims. I remember the lengths that my Christian colleagues had to go to observe Christmas. In Saudi Arabia then, foreigners could be deported for possessing symbols of other religions, which were forbidden upon entry into the kingdom. Nevertheless, residents of my expatriate compound secretly constructed nativity scenes inside their homes. In the medical center where I worked, some Christian nurses would hide their crucifixes under their clothes. A nurse from London had an exquisite gold crucifix that she had hired a Saudi jeweler to make—illegally—based on another crucifix the nurse had brought—illegally—into the country. I studied her gold cross one evening in the ICU as we worked on a patient together, thinking about how much trust was required to make that holy symbol in secrecy.

Many of my male colleagues—Saudi and non-Saudi—were enormously supportive of me, including my department chair and the hospital CEO, who were forward-thinking leaders and created numerous opportunities for women. But some colleagues were themselves ultraconservative fundamentalists and could not relate to a woman as a peer. Because of them, I felt invisible and silenced at work.

A British-born expatriate with a New Yorker’s brash personality, I quickly grew exasperated with the country’s gender apartheid and institutionalized male supremacy. I tried to tell myself that every new slight would someday make a good after-dinner story (and, indeed, at one point I had so many I wrote a book about it). But I was angry at the puritan overlords who were oppressing women—and, in doing so, often emasculating their menfolk. I was angry that this oppression was performed in the name of Islam, when Islam to me was a source of liberation, free-thinking, and autonomy, including for women and girls.

Two years into my work as a senior physician, I recognized there was no way forward for my career. In Saudi Arabia, I would remain stuck in the same role, however hard I worked. The novelty of being in the kingdom had worn off, and its gender restrictions were feeling increasingly punitive. I missed the diverse cultures of London and New York. I missed movies and books. I missed mixing with friends and colleagues.

I decided to resign. The same day I gave my notice, I came home and switched on the TV to see the World Trade Center on fire. I watched the first tower collapse and a second plane impale the other tower.

As for many people, the terrorist attacks of September 11 changed the course of my life. Within my personal and professional circles, I found myself continually asking myself the same two questions: What forces are driving Muslims to commit terror? And how can this cycle be broken? In the years ahead, I would become a fierce critic of Islamism, a form of political totalitarianism with twentieth-century roots in Egypt’s Muslim Brotherhood that masquerades as my religion of Islam. Six weeks after 9/11, I left Saudi Arabia with a new sense of purpose—believing in my heart that nothing would change in the country I was leaving, so set was it in its fundamentalist ways.

Around that time, the prominent British department store Harvey Nichols had just opened a branch in Riyadh. I remember visiting one evening very excited to look at the make-up section—an extraordinary offering in those days. But trying on lipstick in public was taboo. Considerately, Harvey Nichols had set up a private room where women could safely apply their make-up, without Saudi men—including the religious police—looking on.

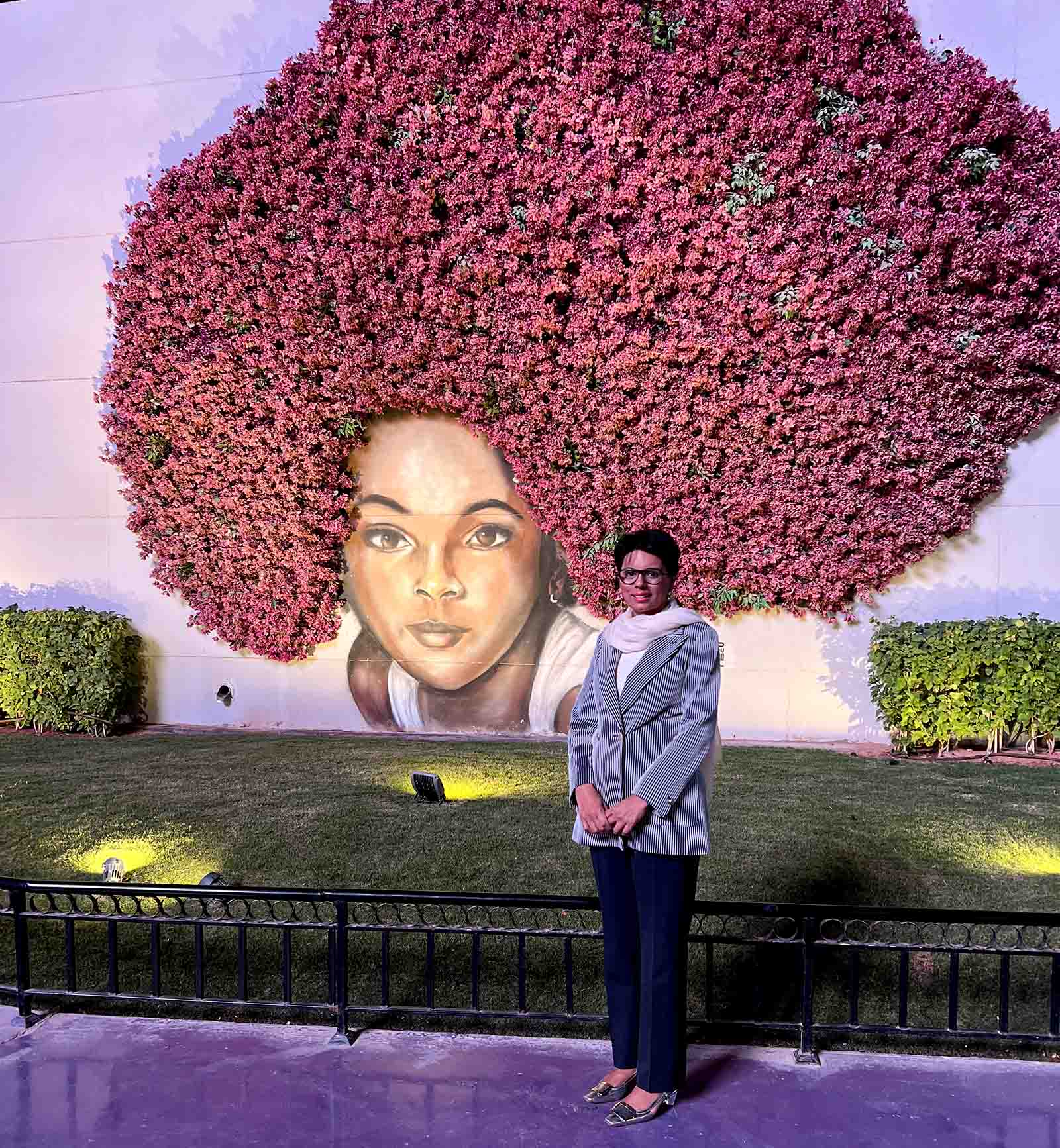

Weeks into the Iranian protests, I visited Saudi Arabia in October as a guest of the Muslim World League to meet its secretary general, Sheikh Mohammad bin Abdulkarim Al-Issa. Headquartered in Mecca but not part of the Saudi government, the Muslim World League is a humanitarian NGO and the largest organizational humanitarian body representing the Muslim world, with representatives from every Muslim-majority nation and territory serving on its supreme council. Al-Issa had heard of my televised appearances challenging some of the Western criticism of the kingdom. Interested in what I had to say, the Muslim World League invited me to Riyadh for a conversation with its leader and a tour of the new Saudi Arabia.

This trip was the first time I’d been to the country since 2010. My first clue about all the changes that had occurred was the security personnel at the airport in Riyadh. I had never seen Saudi women serving as police officers and soldiers before. As the passengers in my line were searched, I could see both how different things were now—having women in such positions of authority had previously been unthinkable in the kingdom—and how much cultural conservatism remained—security guards exclusively searched people of the same gender.

In Riyadh, I was immediately struck by the greater visibility of women in public spaces. They moved freely on the city streets. While most of the women I saw were modestly dressed, I saw some in knee-length sundresses, their legs bare. Others wore skinny jeans, tank tops, and midriff-baring outfits. Many did not wear any head coverings, and those who did adopted diverse styles of veiling—from niqabs that concealed all but the eyes, to token scarves (like the one I wore during much of my visit) that were more accessories than anything else. What coverings I saw were often elaborately printed and brightly colored.

The scene on Riyadh’s streets was so much more vibrant than what I had experienced even a decade earlier. The ubiquitous black cloaks that had once enshrouded the city’s women were all but gone. Patrols of religious police—before a common sight—were nowhere to be seen. In stores, women workers served women shoppers. And astoundingly, women were driving cars—a basic right that had been denied until 2018. Women friends drove me around Riyadh unchaperoned. One of my male friends apologized for picking me up in his wife’s car—his was in the shop—and politely ignored my visible shock. Yes, Saudi women had long owned cars—to be driven by their male chauffeurs—but to have cars of their own that they actually drove on the city’s streets?

Curious, I asked my driver one day to let me take his car for a brief spin. It took him a while to understand that I was asking him to step out of the driver’s seat and into the passenger seat, and he seemed simultaneously entertained and anxious about my ability to handle the steering wheel. As for me, driving for the first time on streets I knew well was the most surreal moment of my trip. It felt like driving on the moon.

As part of my tour, I visited the Ministry of Defense’s Strategic Center for Intellectual Warfare, which seeks to study and combat extremism. There, I was struck by how the public relations team was comprised wholly of women, who delivered their presentations to gender-mixed audiences from a stage—some wearing niqabs, others in hijabs. Through my own initiative, I also arranged a visit to the newsroom of the Arab News, one of the Middle East’s most highly regarded English-language newspapers. Noor Nugali, a senior editor, met with me and ended up assigning a piece I pitched to the opinion editor, Lojien Ben Gassem Abdulfattah. Both women were not just accomplished Saudi journalists, but they were also helping drive public discourse in the kingdom and beyond.

Over the rest of my ten-day stay in Saudi Arabia, I moved freely across the country—this time, carrying my own passport. (Today, women in Saudi Arabia can travel without the permission of a male guardian, and they can travel alone on pilgrimages.) I spent a day in Mecca performing the umrah, the lesser, non-obligatory pilgrimage. Soon after dawn prayers, I set off for Medina, the second-holiest city in Islam, where I planned to worship at the Prophet’s Mosque. Back in 2010, I had made the same trip from Mecca to Medina by car, a grueling three-hundred-mile drive that had ended with a female guard at the mosque turning me away because I had lacquer on my nails. This time, the high-speed rail took me to Medina in barely two hours, and I entered the mosque—the location of the Prophet Muhammad’s tomb—without any comment on my (still manicured) nails.

As I prayed in the small, highly sacred enclave known as Rawdah Al Shareifah (the Garden of Eden), I noticed the women around me were Pakistani. They spoke in Punjabi and seemed to be from a rural part of the country, based on their dress and colloquialisms. I surmised that they were Shia Muslims, given how they sometimes prayed in the direction of the Tomb of the Prophet rather than toward Mecca. This was noteworthy. Saudi society had repressed the religious freedoms of Shia Muslims when I had lived in Saudi Arabia, in line with the exclusionary tendencies of ultraorthodox Sunni Wahhabism. Even native-born Shia Muslims had been forced to conceal their faith lest they face discrimination in the workplace or suspicions about their loyalty to Saudi Arabia. While the kingdom continues to restrict Shia practice—among other things, it still outlaws the building of Shia mosques except in one of the country’s thirteen provinces—it recently lifted restrictions on publishing and distributing Shia religious materials. Prominent Shia clerics like Sheikh Hassan al-Saffar now speak publicly in defense (and sometimes even self-criticism) of the country’s Shia minority, about 12 percent of the Saudi population. And there is fresh hope that sectarian strife will diminish further, given the agreement that Saudi Arabia and Iran reached in March to resume diplomatic ties—which were officially severed seven years earlier after the kingdom’s execution of a high-profile Shia cleric.

At restaurants, complete strangers—men and women—would learn that I was from America and come up to talk to me. They wanted to know what I thought of their country. They also asked me what was wrong with America. They noted that crime was rising there, and they also expressed concerns about pro-LBGTQ content on streaming services like Netflix, especially in programs geared toward young children.

That was one side of the new Saudi Arabia’s take on gender and sexuality. At the Riyadh Boulevard, a massive entertainment complex, I saw another. There, I spotted a teenage Saudi girl in combat pants and pigtails learning to skateboard by herself. She looked like any American teen, and I was struck by the confidence she exuded. Again and again, she fell, and again and again, she got back up on her board. After seeing her take several hard spills, an older Saudi boy politely asked if she wanted some tips. Agog, I watched the girl skate with the boy’s help as her mother and sister cheered her on.

What had changed in Saudi Arabia over the past few decades? A report by the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace describes how the reforms began with King Abdullah bin Abdulaziz Al Saud, who ruled from 2005 to 2015. He and his successor King Salman bin Abdulaziz Al Saud took measured steps to marginalize religious hardliners and roll back fundamentalist policies. Those efforts have expanded under the Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman (widely referred to as “MBS”), who succeeded his father as prime minister last year and is now considered the country’s de facto ruler. In 2021, MBS appeared to make a definitive break with the country’s puritanical past, publicly stating that Saudi Arabia was no longer “committed blindly” to any “certain school or scholar.”

For their part, the authors of the Carnegie report on Saudi Arabia are cautious about reading too much into these recent shifts in power away from the kingdom’s religious hardliners. “Because these alterations amount to reshufflings rather than redesigns, they may be reversible or may simply be the endgame in themselves,” scholars Yasmine Farouk and Nathan J. Brown write. “There have been some suggestions of marginalizing but no frontal assault on Wahhabi teachings; long-standing structures have survived, apparently immune and adapting to existential challenges, at least for now. Nothing is being wholly dismantled, but everything is being changed.”

My own view is that the changes are more deeply rooted. Long before 9/11, Saudi Arabia itself had been victimized by Islamist violence, including a 1995 car bombing at a national guard facility and the 1996 Khobar Towers bombing—two of al Qaeda’s earliest acts of terror. Rocked by 9/11 and the key roles that Saudi nationals had played in the attacks, the kingdom took steps to strangle terror-related financing and root out violent Islamist operatives, even as domestic terrorism continued to rage (including a 2003 attack in Riyadh that killed thirty-five and injured hundreds, many of whom were treated by my former hospital colleagues). In more recent years, the government’s crackdown has extended to stamping out Islamist ideology, with the shutting down of madrassahs and other religious organizations with ties to the Muslim Brotherhood (itself designated as a terrorist organization in Saudi Arabia), the banning of Muslim Brotherhood educational materials and libraries, and the development of school curricula to combat such ideas.

The overreach of the religious police eventually prodded the government to act on this other form of domestic extremism as well. The tipping point was arguably a 2002 fire at a girls’ school in Makkah. Religious police on the scene forbade students in the burning building from leaving without their veils. That decision was blamed for the subsequent deaths of fifteen girls and triggered widespread horror and outrage. As public sentiment turned against the religious police, the administration of King Abdullah cracked down, greatly curtailing their power. In 2017, the religious police were finally disbanded.

The Carnegie report singles out Al-Issa, the Muslim World League’s secretary general, as one of the Saudi leaders most responsible for moderating the country’s approach to religion. Before the crown prince appointed him to that role as well as a spot on the Council of Senior Scholars, the kingdom’s governing religious body, Al-Issa had already distinguished himself as a progressive reformer, filling court benches with centrist Islamic jurists when he previously served as the country’s minister of justice. A trusted advisor of the crown prince, Al-Issa has led the regime’s efforts over the last several years to denounce the extremism of the Muslim Brotherhood and other Islamist organizations.

As an internationally recognized advocate for moderate Islamic perspectives, Al-Issa has become particularly known for his interfaith outreach. In 2020, the seventh-fifth anniversary of Auschwitz’s liberation, he became the most senior Muslim cleric to bring a delegation to the concentration camp. There, he led Islamic prayers, bowing and prostrating in supplication on the ground of Auschwitz and acknowledging the Holocaust as a crime against humanity.

Al-Issa has hosted Christian, Jewish, and Hindu religious leaders in Saudi Arabia and addressed major evangelical Christian gatherings in the United States. He has met with Pope Francis and signed a bilateral memorandum of understanding—the first such agreement between the Muslim World League and the Vatican. And last Christmas, he publicly stated that Muslims were not violating any tenet of Islam by wishing their Christian friends and acquaintances season’s greetings at Christmastime—a seemingly innocuous statement that drew a backlash from hardliners, but that Al-Issa robustly defended with reference to scripture.

Importantly, Al-Issa has also made a number of bold public statements rejecting the use of violence in the name of Islam—including inside Israel. For instance, during the Islamic Hajj pilgrimage last year, he delivered its key sermon, the address from Mount Arafat, in which he called for unity among Muslims and emphasized Islam’s humanitarian values. (The sermon prompted a firestorm of criticism, with Qatari social media even labeling him a “Zionist.”) As a sign of his organization’s commitment to nonviolence, last fall Al-Issa unveiled a replica of the Knotted Gun, the Swedish sculptor Carl Fredrik Reuterswärd’s iconic symbol of nonviolence, as the centerpiece of the Muslim World League’s gardens in Riyadh.

When I met with Al-Issa, I covered my hair during our meeting as a show of respect to his religious office, but no one told me to do so—as would have been mandatory in the Saudi Arabia I’d previously known. When we stood for a group photo, the organization’s photographers politely asked me to wear my hair as I typically appear in public.

The staff joining us were all women, and I learned that one of Al-Issa’s senior advisors, Haya Al Jadouah (who had been responsible for my invitation to visit with Al-Issa), had received all her education—including her doctorate in digital media communications—in Saudi Arabia. At the time I had lived there, there had been few medical schools or residency and fellowship programs, and what institutions of higher education existed had been dominated by religious studies. Most of the Saudi doctors I met then had studied internationally. It seemed that the secular educational system that had trained Al Jadouah had been assembled from scratch over the last two decades.

When we finally sat down to talk, I was struck by how candid Al-Issa was about his fears of a religious war between Ukraine and Russia. Holding his head in his hands, he despaired that two Christian nations—Russia and Ukraine—were so casually using the language of martyrdom and holy war to describe their conflict. After all, along with Pakistan and the United States, Saudi Arabia had been a patron of the mujahideen—the ultraorthodox Islamist fighters who had beaten back the Soviet Union in Afghanistan—and the kingdom later paid a bloody price for that support, as the mujahideen’s austere fundamentalism became the template for violent Islamist groups across the region and eventually the world. To me it seemed that Al-Issa—entirely Saudi in origin, education and practice—had internalized the lessons of that disastrous history of violence.

The prominence of moderate religious leaders like Al-Issa in today’s Saudi Arabia speaks to the discreet and pragmatic approach that Saudi rulers have taken in recent years to rein in the country’s fundamentalism. Rather than seeking to dismantle the religious machine outright, Crown Prince MBS (and before him, King Salman) empowered progressive Saudi theologians like Al-Issa and diversified the country’s schools of Islamic thought. They kept some of the older ultraconservatives but diluted their influence by consulting with them less often. As the Carnegie report concludes, MBS’s eventual public break with a “blind” commitment to Wahhabism in 2021 “fits with the Saudi monarchy’s practice of creating parallel institutions, religious interpretations, and (in this case) religious leaders to compete with and eventually replace the old ones, without explicitly discrediting their predecessors.”

Given this subtle approach, it is no wonder that many people in the West have been unaware of all the reforms that have transpired in Saudi Arabia over the past decade and a half. Saudi Arabia has maintained Islam at the center of the state, but its rulers have deftly weakened and delegitimized the extremist clerics who once wielded such total power over the Saudi people. For that reason, I am more hopeful than the Carnegie scholars are that the reforms launched by King Abdullah, continued by King Salman, and accelerated by Crown Prince MBS will be permanent. The fundamentalists have been defanged, and all the changes in Islamic jurisprudence and legal codes mean there is no turning back, even if pockets of hardline resistance and resentment remain.

This is not to say that Saudi Arabia has become a liberal state in the Western mold. The diplomatic tensions between the United States and Saudi Arabia over the assassination of the Saudi dissident journalist Jamal Khashoggi speaks to the gulf that still exists. (Western intelligence agencies allege the assassination was personally authorized by MBS, which he denies. Under Islamic law, a wrongful death must be legally compensated with damages, and the crown prince—who has acknowledged that the atrocity occurred “under his watch”—has rendered such payments to the family in Riyadh, who accepted them.) Wherever I went on my last year visit to Saudi Arabia, the Khashoggi incident would come up, along with concerns about how U.S. president Joe Biden had made Saudi Arabia a “pariah“ in response to the assassination.

It is important to recognize that Saudi culture is deeply defined by honor, and many Saudis sees the horrific butchering of Khashoggi—much like the shamefully homegrown origins of al-Qaeda—as permanent stains on that honor. At the same time, the liberal-minded Saudis I talked to were frustrated by how the West has sought to isolate the country following the assassination, even as Saudi Arabia has taken such bold steps in recent years to put forward a mature and moderate Islam and show openness not only to its citizens but also to the outside world. It comes across as hypocritical, too, for the West to talk about human-rights atrocities in Saudi Arabia when there has been no accountability for the costs of its colonial interventions throughout the Muslim world. Indeed, a recent Brown University report estimates that over 4.5 million people have died in the “post-9/11 war zones of Afghanistan, Pakistan, Iraq, Syria, and Yemen”—some in combat, but many more due to infectious diseases, malnutrition, and toxins unfurled by war and worsened by the ruined public health infrastructures in each country.

Sadly, the West nowadays is exerting pressure on a country that has made determined efforts to reform—Saudi Arabia—while doing little where its influence could be more decisive—Iran. Months into the protests—after the killings of hundreds of protestors—the United States finally drafted a resolution to expel Iran from the United Nations Commission on the Status of Women. In early December the U.S. and Canada announced the sanctioning of three Iranian officials said to be involved in the detention of protestors. Canada went further, banning about 10,000 members of the Iranian Revolutionary Guard Corps from entering the country.

What accounts for the West’s tepid policy response in the wake of such a dramatic pro-democracy uprising by the Iranian people? Perhaps Western governments felt they had little ability to influence what was happening in Iran beyond sanctions and other measures already in place. A more cynical take—one that resonated inside Iran—was that countries that relied on oil from Iran, one of the world’s top petroleum producers even with existing sanctions, had no interest in confronting its repressive regime, especially when their economies were already facing inflationary pressures in the wake of the Covid pandemic and war in Ukraine. In any case, in comparison to the near-unanimous Western support for Ukraine after Russia invaded it, which included providing arms and ammunition to Ukrainian forces, the international response to Iran’s protests was largely symbolic.

Exhibitions in the European parliament honored protesters killed by Iranian authorities. Social media feeds featured celebrities cutting their hair in solidarity with Iranian women. In New York, where I live, a well-intentioned NGO worked with artists to put on “Eyes on Iran,” an exhibition of works by Iranian and Iranian American photographers. Reading about it reminded me of the emotions I felt when I saw an exhibition featuring the photography of Steve McCurry in Paris last summer. The centerpiece was McCurry’s iconic image of a green-eyed Afghani girl, Sharbat Gula, presented alongside a portrait of her two decades later, tragically weathered by the hardship of her life. As powerful as this sort of art can be, I also remember the self-revulsion I felt as I took the images in. The Taliban had just returned to power, and girls and women were once again living under fundamentalist oppression. Here I was, a privileged woman living in the West, standing in an impeccably lit exhibition hall and observing, glamorously, a community’s suffering from a distance. And now we were collectively doing the same thing with Iran: hosting exhibitions on Iranian anguish while tolerating their oppressors on the international stage.

It is also important to note that the situation in Iran is not merely a matter of civil strife, but has numerous geopolitical ramifications. For example, one underreported angle of the protests is how they were sparked by the death of a Kurdish Iranian woman. The Kurds are the world’s largest diaspora that has been denied nationhood. They fight for independence in Turkey. They carve out autonomous, but internationally unrecognized, enclaves in Syria. They share power in Iraq (where I have met frequently with Kurdish leaders) and have played a vital role in beating back the Islamic State. In Iran, however, Kurds remain a highly persecuted minority.

Their marginalized status was reflected in international news reports, which often reduced the Iranian protests to a simplistic struggle for freedom for Iran’s women and girls. The ethnic identity of Amini—who hailed from Saqquez, a Kurdish province in northwestern Iran—received little interest, even though for her Kurdish Iranian community, the uprising in her name was something much more: a fight for the right to their identity, language, and culture within a repressive Iranian Islamist theocracy. Meanwhile, the Farsi translation of “Jin, Jiyan, Azadi”—a Kurdish phrase coined by the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) inside Turkey and widely used to show solidarity across the diaspora—became a rallying cry for a protest movement by ethnic Iranians on behalf of Iranian democracy, an “erasure” of its ties to the fight for Kurdish self-determination and statehood.

In spite of the many human rights arguments on behalf of regime change in Iran, international support was minimal during the protests. After two decades of using its military to pursue a fantasy of installing liberal democracies in its own image across the Middle East, the United States clearly had no stomach for further entanglements in the region. And even though it has poured tens of billions of dollars into assistance for the Ukrainian people in their struggle against Russia, it would not do the same to empower the Iranian people to achieve regime change themselves. “It is amazing that the lesson so many Americans have taken from the wrong actions of the past is to choose inaction,” the Iranian American poet Roya Hakakian said in a December interview. “History has shown us that inaction can be as damaging as wrong action, and a sin equally as great.” In their meetings with U.S. secretary of state Antony Blinken and other Biden administration officials during the protests, Hakakian and other activists made the case that America could be providing useful assistance even short of arms. For instance, satellite phones and Internet service would help protesters coordinate with each other and mobilize on the streets in spite of the regime’s efforts to curb online access and shut down social-media platforms.

Nothing of the sort happened, however, and the protests died out, put down by the government’s ruthless crackdown. To pay tribute to the regime’s victims, the Iranian musician Shervin Hajipour wrote the song “Baraye” (“For the Sake of”), which became a global anthem for the protests. Those who died, Hajipour sings, merely wanted a “zendagi ma’mouli”—an ordinary life. The word “zendagi” carries the same meaning in Farsi and Urdu, my mother tongue. Months later, the song still makes me tear up.

Now that the protests seem to be over, what hope is there of an eventual overthrow of Iran’s hardline theocratic government? In my view, Saudi Arabia provides a roadmap for those who hope to escape fundamentalism and Islamist extremism. When I lived in the kingdom two decades ago, it seemed unimaginable that the status quo would ever change. But things did change, with time. The reforms came largely without bloodshed or major upheaval, and they appear to be deeply rooted, enjoying widespread public support and reaching far into the ranks of the country’s clerical leadership.

The Iranian protests have already shown how much the first condition of grassroots societal change—popular will—is already a reality. During the months of turmoil, Iranians from many regions of the country unified across lines of class, gender, and profession to express their outrage, their words and actions underscoring a shared nationhood and dignity and common culture and history. Even if the demonstrations have ended for now, the fact that Iran is potentially an economic powerhouse with a central position in the world’s petroleum economy—unlike other pariah nations like Afghanistan and North Korea—suggests that, like Saudi Arabia, it will not be able to keep its population repressed and infantilized for too much longer.

Yet it is hard to see how the country’s ruling theocrats will be shaken from power without some sort of intervention from the top. In Saudi Arabia’s case, the brave and daring dissidents who protested the kingdom’s fundamentalist policies over the decades created an urgency for reform and made people aware of the extent of the repression. Many Saudi dissidents remain imprisoned to this day, another sign of the limits of the monarchy’s policies of openness. But as I described earlier, marginalizing the country’s Islamist clerics required a movement from above as well as one from below—a political vise that eventually crushed the ultraconservative orthodoxy of the old guard.

As for pressure from the international community, it played a more minor role in kindling Saudi Arabia’s reforms than we overseas observers might like to think. In fact, I would argue that the impetus for change came less from outside hectoring about the kingdom’s human rights record and more from the country’s own shame and suffering about its role in nurturing the violent Islamist extremism that led to al-Qaeda and 9/11. Likewise, the most effective weapons employed against the kingdom’s religious hardliners were not arms supplied by foreign powers, but the potent ideological antidotes available within Islam itself.

Dissidents in Iran need to cultivate their own Al-Issas: liberal and pluralist-minded clerics waiting to be empowered and legitimized, who could dilute the repressive form of Islam that now holds sway. This is work that will span decades. And it will likely require more than street demonstrations, as hopeful, courageous, and inspiring as they are. As many of the protesters themselves recognize, they need international support to go any further, and that support will continue to be improbable under current geopolitical conditions.

The Iranian regime must realize the global clout it now wields amid jittery energy markets and persistent inflation. It has been nimble in managing international sanctions so far, and once the moribund Iran deal runs into its 2025 sunset provisions, Western nations in search of cheaper oil may not be willing to put up further resistance. Furthermore, Iran recently signed a twenty-five-year deal with Venezuela, home to the world’s largest oil reserves. Iran will share its refining technology, expertise, and distillate in exchange for Venezuelan crude. Not only are the Iranian regime’s economic prospects looking brighter, but it seems to have shored up some of its other vulnerabilities, too. For instance, in addition to the recent détente between Iran and Saudi Arabia, the long-running civil war in Yemen—widely seen as a proxy war between the two regional powers—appears to be ending. These developments will ease the external pressures being placed on Iran’s theocracy, allowing it to focus on suppressing its internal enemies.

In short, Iran’s geopolitical position seems sound, and internally, I still do not see the political and social conditions that would allow for major reforms in the treatment of women and the overturning of Islamist ideology. Indeed, while Saudi Arabia has slowly but steadily pulled itself out of extremism after 9/11, Iran’s fundamentalism and totalitarianism have only deepened.

Recently, I shared my thoughts about the parallels between Saudi Arabia and Iran with a Los Angeles-based Iranian activist I know. After listening to my hopeful scenarios of possible Saudi-like reforms in Iran, he sounded a cautionary note: “We had eighty years of liberal reforms in Iran, but the extremists were always there.… They had never gone away.” He urged me to read about Reza Shah Pahlavi, the first leader of the Imperial State of Iran, who was succeeded by his son Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, the shah ousted in the 1979 Iranian Revolution.

Born Reza Khan, the first shah was an officer in Iran’s Cossack Brigade when he and his supporters seized power in 1921. Over the next two decades, he instituted ambitious infrastructure programs and sweeping educational, military, and economic reforms, building the foundation for the modern Iranian state. Much like Saudi Arabia’s recent rulers, Reza Shah sought to rouse the country’s national identity as a way of bridging its numerous tribal, ethnic, and provincial divisions. And like King Salman and MBS, he pursued policies of pluralism and openness. He reformed the judiciary along the lines of France’s multi-tiered secular system. He expanded schooling for both boys and girls. And he marginalized the reactionary clergy, surrounding himself instead with forward-thinking advisors—many trained at Western institutions.

However, Reza Shah’s reform agenda faltered as his rule became increasingly autocratic. His regime tightly controlled the press, maintaining a state monopoly on radio broadcasting to push its propaganda. It rigged elections for the shah’s favored candidates and imprisoned would-be challengers. During World War II, the Allied Powers grew impatient with Reza Shah’s corrupt and ineffectual regime and forced him to abdicate. His son succeeded him, but by then, a reactionary tide was forming. As the historian Shaul Bakhash writes in The Fall of Reza Shah, the first shah had not yet secured the “institutions, political practices, and habits of mind” that could have carried Iran toward a lasting democratic pluralism. Crucially, Reza Shah’s top-down approach in transforming Iranian society had meant that there was a lack of grassroots support for his reforms. The fundamentalists reemerged and rolled back decades of liberalization.

Could the same thing happen in Saudi Arabia? I’ve thought about that a great deal since learning more about the reversals of Iran’s own reforms. I can’t help but think, too, of the documentary images I’ve seen of a dazzling Kabul in the time before war and fundamentalist rule, or Latif Al Ani’s poignant photographs of a cosmopolitan Baghdad in the time before autocracy and anarchy. Cynics would say that the scenes I witnessed in Riyadh are just a brief interlude before another descent into puritanism. Perhaps Iran will be the model for Saudi Arabia rather than the reverse. Perhaps the “oil for security” bargain that has tied together the kingdom and the United States for eight decades will unravel, and without sufficient pressure not to be a “pariah,” Saudi Arabia will return to its theocratic past.

I do not share this view. The reforms are just too deeply woven into the social, political, legal, and economic fabric of the new Saudi Arabia. When it comes to the liberalization of recent years, the kingdom is all in. That said, I see how Saudi Arabia is adapting to new geopolitical realities. The United States is experiencing an unprecedented contraction in global influence, and Saudi Arabia is nimbly pivoting eastwards, with a nod to the emerging multipolar world order. China has avidly courted Saudi Arabia, recognizing it as a central player in the region, and Saudi Arabia, in turn, no longer views itself as dependent on the protection of a sole superpower. Meanwhile, a recent Gallup poll of 13 Muslim-majority nations found that Saudi Arabia’s leadership has a substantially higher approval rating than Iran’s (39 percent versus 14 percent). Much of the Muslim world apparently prefers governments that prioritize individual freedom and economic stability, both of which are necessary for self-actualization.

For all these reasons, I am hopeful about the staying power of Saudi Arabia’s reforms and the long-term prospects for democracy in Iran. And I am optimistic, too, about the future of Islam. Over these last two decades, I have made it my personal mission to understand violent extremism and learn how to combat it. My efforts have taken me across four continents to meet victims of genocide and talk to rehabilitated jihadists and the professionals who work with them. In New York, I continue to work with survivors of the September 11 terrorist attacks at my NYU Langone office, where we treat the long-term sleep disorders they have suffered ever since the horror of that day. Across my work in medicine and activism, my faith has always inspired me to reject extremism and violence and embrace freedom and compassion.

My belief is that this face of Islam—the true Islam—will eventually gain ground in countries like Iran, as it has in Saudi Arabia. The fanaticism that animates the Iranian theocrats who execute, maim, and silence their opposition needs to be pushed aside, and sooner or later leaders will rise up to do just that. Iran’s street protests may have been stifled for now, but sooner or later new voices will rise up to continue them. Let us hope that when they do, all the pieces will be in place to put an end to Iran’s fundamentalism, bloodlessly and decisively.

Qanta A. Ahmed Qanta A. Ahmed, MD, is a senior fellow at the Independent Women’s Forum and a life member of the Council on Foreign Relations.

- Follow us on Twitter: @inthefray

- Comment on stories or like us on Facebook

- Subscribe to our free email newsletter

- Send us your writing, photography, or artwork

- Republish our Creative Commons-licensed content