It’s not 1975, and we aren’t Americans and South Vietnamese fleeing the advancing Viet Minh forces. It’s forty-five years later, in the middle of March, and we are mostly Australians (along with some New Zealanders) fleeing the contagion of the novel coronavirus.

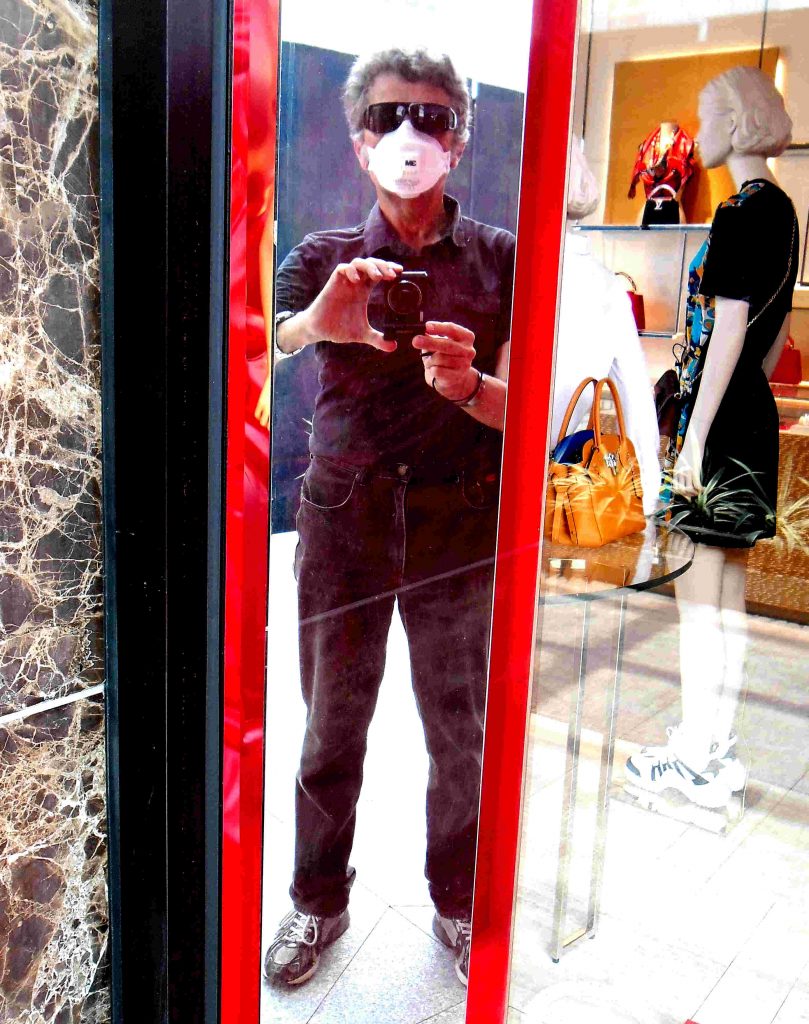

Amid rumors that the country will soon halt international flights, I board Vietnamese Airlines Flight VN773 out of Ho Chi Minh City, formerly known as Saigon. Bound for Sydney, the plane is scheduled to take off on this balmy Sunday night with a full load of passengers. When I flew in just one week before, my plane had been almost a third-empty. Only the cabin crew wore masks. Back then, the number of reported cases worldwide was under 100,000, with most of the infected in China and only a few dozen in Vietnam. But on tonight’s flight, the faces of all the passengers are half-hidden in paper filter masks. Cases in China and elsewhere have surged, and the World Health Organization, which announced just days earlier that the COVID-19 outbreak was a pandemic, is urging governments around the world to mobilize to stop its spread.

On the night of our evacuation, there are no tanks in the streets, and no artillery shells or small-arms fire lighting up the sky as in 1975. But the city is shifting into a lockdown. Having already closed all schools, the government yesterday ordered nightclubs and bars to shutter While the rumors of a total shutdown of international travel turn out to be untrue, Vietnam is now refusing most entry visas and quarantining those individuals who do make it into the country. Foreign tourists are leaving in droves. One Australian couple sitting across from me say they were denied entry into Vietnam because they had arrived from South Korea—at that time, a coronavirus hot spot.

When Saigon was evacuated on April 30, 1975, eighty-one helicopters flew 1,373 Americans and 5,595 Vietnamese out of the city. Tens of thousands of other Vietnamese refugees made their way across the water on fishing boats, barges, and makeshift sampans to seek refuge on the U.S. Seventh Fleet’s warships anchored offshore, fearing reprisals from the advancing North Vietnamese forces.

COVID-19 is more of a terrorist than an invading army. It seeks out a seemingly random selection of victims, though it is most lethal for those who are older or have preexisting medical conditions. In China, where the virus is believed to have originated, high smoking rates and the toxic soup of air pollution in industrial cities have made the population there particularly vulnerable.

I remember a conversation I had with my shuttle driver on the way to the airport. He said his wife and three children live in his hometown of Hoi An, in the pinch-waisted central part of Vietnam. He spends just four holidays a year at home: one for Tet, the lunar new year festival, and one each for his children’s birthdays. He said he’s lucky to have a good job ferrying passengers to and from the airport, but the future is looking decidedly bleak. Even though Vietnam calls itself a “socialist republic,” there are no unemployment benefits or public pensions. Schooling and health care are not free. In other words, there is not much in the way of a safety net to cushion the economic impact of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Then again, the situation in my country, Australia, is worrisome, too. The principal reason that I came to Vietnam was to get my teeth fixed; the same dental procedure in Australia would have cost three or four times more. With the coronavirus spreading, I’m anxious about my future livelihood. The government just announced that all Australians returning from overseas must self-quarantine for fourteen days. When my plane lands in Sydney, I will be under a kind of house arrest and unable to earn an income. In an economy that rejects permanent employment, I have no paid sick leave to fall back on. Perhaps there will eventually be some sort of bailout from the federal government to help people who have been economically affected by the pandemic. That said, there are limits to Australian socialism, particularly if the recipient is not destitute. (Such limits, of course, do not apply to banks or financial institutions.)

The Vietnamese cabin crew are polite and efficient. They serve us dinner, and for a moment the passengers look normal again, our masks no longer hiding our faces as we eat our hot meals. I chew my pork and rice cautiously with my newly crowned teeth.

Our plane is now flying over what the Vietnamese call the East Sea and the rest of the world knows as the South China Sea, a body of water whose islands and undersea wealth are claimed by several nations—most aggressively, China. This is one of the world’s most important trade routes, linking China and its markets across the globe. But fewer goods are flowing across it nowadays: trade volumes have sunk dramatically as China has struggled to contain the virus.

Our dinners eaten and trays dispensed with, we don our masks again. The cabin lights are darkened shortly afterward, and the passengers settle down to enjoy a video or catch what sleep we can. Next to me, an elderly Vietnamese lady begins to doze, her head toppling gently onto my shoulder. I watch a long movie and find afterwards that I cannot sleep. Instead, I watch the dawn gradually peep in through the darkened cabin windows.

We touch down in Sydney on a cool, drizzly morning. There is an air of finality as we leave the plane. This will be one of the last flights on this route, at least for the time being.

Igor Spajic Igor Spajic is the author of books on low-cost car restoration and vintage science fiction and a longtime contributor to Restored Cars Australia.

- Follow us on Twitter: @inthefray

- Comment on stories or like us on Facebook

- Subscribe to our free email newsletter

- Send us your writing, photography, or artwork

- Republish our Creative Commons-licensed content