It’s one of the most grueling, dangerous jobs on Earth. Workers at the Cerro Rico mines near Potosí, Bolivia, toil from dawn till dusk in constricted, dust-filled passages, knowing they might die at any moment and likely will never reach middle age. Now, Cerro Rico has become a leading tourist attraction—despite the risks, the plight of the miners, and the downward spiral of a community that has fallen far from past wealth and glory.

“It’s like going to the zoo, looking at animals,” said Julio Morales, an ex-miner turned mining tour operator turned activist, who believes the visits are getting out of hand. “The mines are not a game.”

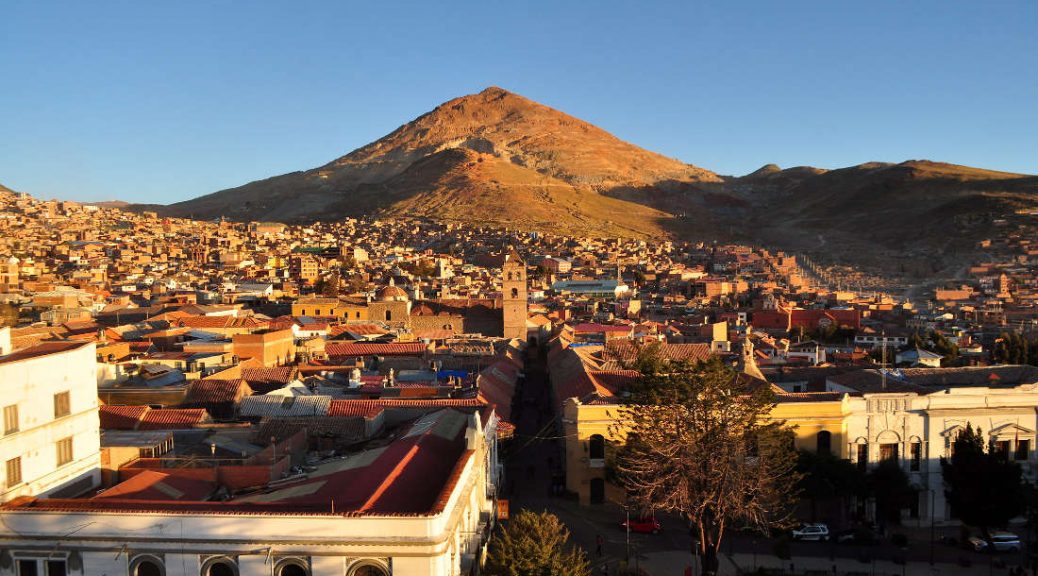

In the sixteenth century, Spanish conquistadors discovered silver inside a mountain overlooking a remote village in the Andes. They named the mountain Cerro Rico, “rich hill.” At the time, Cerro Rico contained the largest silver deposit on the planet. The precious mineral was so abundant it bankrolled the Spanish empire and transformed the village of Potosí into a world economic powerhouse. By 1611, the population had risen to 160,000, making Potosí one of the largest cities on Earth.

As wealth flowed out of the mines, indigenous and African slaves flowed in. The Spanish forced the slaves to live underground—often for days at a time—enduring brutal conditions as they labored to extract the silver ore. Many never resurfaced, succumbing to hunger, disease, and overexertion. By the time the Spanish departed Bolivia three centuries later, millions of workers had perished, earning Cerro Rico the nickname “the mountain that eats men.”

Today, the silver that made Potosí famous for its extravagant wealth is all but depleted, but miners continue to work the mountain. In addition to trace amounts of silver, the sought-after minerals are now tin, lead, and zinc—used in the manufacture of paint, ceramics, pharmaceuticals, textiles, batteries, auto parts, and electronics. The workers at Cerro Rico are no longer slaves, but their working conditions are still dangerous. Approximately half of Potosí’s mines are at least a hundred years old; some date back half a millennium. Wooden planks hewn in colonial times still brace many of the 20,000-plus tunnels crisscrossing the mountain. Cave-ins are common, and they have become even more so in the past decade, as miners have shifted from following veins to indiscriminately removing mass quantities of rock from shafts, or even mining at the surface of the mountain. Taking these more aggressive approaches extracts more of the Cerro Rico’s ever-diminishing minerals, but they also weaken the mountain’s structural integrity.

In 2011, a sinkhole opened at the peak of Cerro Rico. The government filled it with cement to stabilize the rock. The summit has continued to cave in slowly, however, and the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), which previously named Potosí one of its World Heritage sites, added the city and Cerro Rico to its list of endangered locations in 2014. A report by UNESCO and the International Council on Monuments and Sites called the situation at Cerro Rico “urgent,” saying that extensive mining had “severely weakened” the upper part of the mountain and resulted in “a significant risk that miners could die from collapses inside the tunnels, as … has already occurred.”

Tom Perreault, a geographer at Syracuse University, describes Cerro Rico today as a “honeycomb.” “There are hundreds of mine openings, and miles and miles of mine shafts,” he says. “It is anyone’s guess how structurally sound the mountain is.” In spite of the danger, Perreault says government officials have little interest in regulating the mining industry, given how important it is to the economy. “They don’t want to kill the goose that lays the golden egg.”

Thanks in large part to relatively high prices for minerals, gas, and other commodities, Bolivia’s economy has grown steadily over the last two decades. The boom allowed Evo Morales, the country’s first indigenous president, to fund dramatic increases in spending on schools, hospitals, and infrastructure, among other things, which experts say contributed to a sharp reduction in levels of extreme poverty during his presidency. (Morales, who had been in office since 2006, won an unprecedented—and, his opponents say, unconstitutional—fourth term in October, but was forced into exile after outside election observers discovered vote-counting irregularities, sparking deadly riots across the country.) Economic growth has tapered off somewhat in recent years, however, as worldwide commodity prices have dropped. Meanwhile, a lack of infrastructure and education has stymied Bolivia’s efforts to pursue alternatives in industries that are not as volatile.

Potosí’s star, of course, faded centuries ago. The hunt for tin, lead, and zinc has kept the mines humming but not brought back the city’s old glory. Once equal in population to London, Potosí is now one of the poorest cities in South America’s poorest country, and there are few employment options in the area. Potosí is located at a high altitude (13,000 feet) in a desert, making farming difficult. Other than mining, the only jobs available are in restaurants and hotels geared to international tourists. Tourism is a growth industry in Bolivia—the World Bank says almost one million foreigners visited the country in 2016, 67 percent more than in 2007—and locals are hopeful that more of these tourist dollars will make their way to the country’s southwestern region. In recent years, dozens of entrepreneurs there have launched tours into the mines, trying to build Potosí’s future on the back of its past.

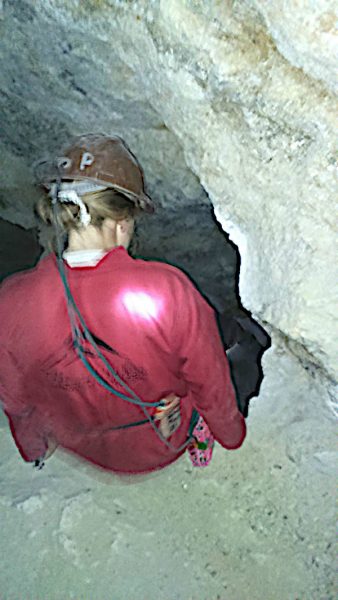

A trip with one of Potosí’s travel agencies normally costs $10 to $20, including protective clothing, rubber boots, and a helmet with a headlamp. Many companies hire ex-miners to lead the excursions. On a recent trip to Potosí, I join a group led by Jose Antonio Ferrufino Ticona, a middle-aged ex-miner who runs Potochij Tours. Ticona started working in the mines decades ago, at the age of fourteen, but he quit five years later after his father, a miner, died of lung disease. (His grandfather, also a miner, had died of a similar condition.) Ticona switched to guiding to escape the profession, he says.

As is typically the case at Cerro Rico, the tour begins with a stop at the local miners’ market, located near the base of the mountain. There, visitors are strongly encouraged to buy gifts for the workers, such as dynamite, cigarettes, and coca leaves (miners chew the leaves to boost their energy and reduce hunger during their long shifts). Though it might be considered poor form, I can’t bring myself to purchase anything. Giving a miner crackers to “perform” for me feels a bit unsettling and suspect.

We get into a small passenger van and drive for a few minutes up to one of the mine’s many entrances. Given how deadly a place Cerro Rico is, the entrance seems rather mundane: a cramped, unlit opening in the side of the mountain, framed and supported by weathered timbers. As our group of six guests approaches in the late morning, we come upon a heavyset tourist from another group standing just outside the entrance. After staring into the darkness, she tells us, she lost her nerve to go in. “I can’t do it,” she says, sobbing.

Over the next two hours, we walk in the darkness through uneven, muddy shafts, squeeze through tight, claustrophobic spots, and gingerly scramble up and down rickety wooden ladders that appear to have been in place for decades. We descend four levels deep into the mine; Ticona says he steers clear of the other ten levels, where there’s increased activity and an increased chance for mishaps.

The Bolivian government once ran Cerro Rico’s mines, but it decided to lease them out to mining cooperatives in the 1980s when worldwide commodity prices crashed. Cooperative mining partners, or socios, pay the government for the right to work sections of a mine. The socios form “workgroups” to extract the minerals from their sections, covering the costs and reaping the rewards of the work done there.

The cooperative mining sector has grown dramatically in recent years. In 2014, there were 113,000 socios representing 155 cooperatives, up from 49,000 partners and 94 cooperatives just six years earlier. But these figures do not account for the day laborers, or “peons,” who make up half of the workforce in the Cerro Rico mines. The socios can tap this pool of contingent labor when mineral prices are high and they can afford the extra help. The peons have no ownership stake and only get paid either a set, pre-determined wage or a percentage of what minerals they collect. A day’s work can earn them as much as twenty-one and as little as ten U.S. dollars—an average to below-average monthly wage in Potosí. Sometimes the peons must even provide their own tools, including dynamite to blast through rock. While socios can potentially receive a big payoff if their workgroup strikes a rich vein, they are often not much better off than the peons, given that they also bear the expenses and risks of the excavation. “The majority of miners are living paycheck to paycheck,” says Kirsten Francescone, Latin American coordinator for MiningWatch Canada, an international watchdog agency. “If they get ahead for a week or two, they quickly fall behind when they get sick.”

Critics say the “cooperatives”—which tend to be run by families or small groups—are nothing more than unscrupulous businesses that exploit their workers. In Bolivia’s nationalized mines, the miners are represented by labor unions and receive fixed salaries and benefits. But the private cooperative sector now dominates the industry, accounting for 88 percent of the country’s mining workforce.

In Cerro Rico, roughly eight thousand people are employed across four hundred mines. (This includes child labor: a 2014 report by the Bolivian national ombudsman’s office said there were 145 child workers at Cerro Rico, most of them between the ages of fifteen and seventeen.) Miners typically work eight to ten hours a day, and sometimes more when the prices of the minerals on global markets fall. But in spite of the constant danger of falls, collapsing tunnels, dynamite blasts, and carbon monoxide, most of these miners have just helmets and rubber boots for protection and use the most primitive tools—dynamite, picks, and shovels—to excavate the tottering mountain. The biggest health threat is silicosis, an incurable lung disease caused by breathing in tiny rock particles from drilling and explosions, yet few miners wear masks. Because of these hazards, Francescone says, the average life expectancy of a Cerro Rico miner is between thirty-five and forty years.

The Bolivian government claims it keeps no national statistics on deaths or accidents associated with the mining cooperatives. Reliable figures are hard to come by, given that police reports of mining accidents—which recorded twenty-two deaths in 2010—suffer from underreporting, even as the number of cooperatives has swelled. One tour operator estimates that each month five to six people die in Cerro Rico, the majority from cave-ins. MUSOL, an advocacy group that works with local women and their families, calculates that mining-related accidents and diseases create fourteen widows a month. “A lot of miners completely understand they are killing themselves,” says William Strosnider, an ecological engineer at the University of South Carolina. “They are making a deal with the devil for higher earnings … but shorter lives.”

Most of these dangers could be avoided if the cooperatives invested in modern mining technologies. For instance, wet drilling—a method of mining that uses compressed air to force water out of the end of drill bits—eliminates almost all the dust that causes silicosis. But the equipment is expensive to purchase and maintain, and the cooperatives argue that they are already on the edges of profitability. They have fiercely resisted any government regulation of their activities, and they have the grassroots power and political clout to punish those who cross them. In 2016, cooperative miners staged nationwide protests, in part calling on the government to relax environmental rules so that mining output could be increased. Bolivia’s deputy interior minister, Rodolfo Illanes, was kidnapped after going to negotiate with the miners at a roadblock they set up outside the capital. The next day Illanes was found beaten to death on the side of the highway. In July, four cooperative miners were sentenced to five years each for the murder.

As our tour group continues exploring the fourth level, we eventually run into a group of miners. A half-dozen men are using well-worn sledgehammers to smash rock from an earlier explosion. None of them wear eye protection or masks, even though a haze of rock residue fills the air in the confined passage, making it challenging to breathe.

Our guide Ticona greets the miners, and we stop for a moment. As he distributes the various presents we bought at the market—crackers, juice, cigarettes, coca leaves—I notice that one of the miners is sitting off to one side. He appears to be a veteran of Cerro Rico, perhaps in his late thirties. Though still early in the shift, he slouches heavily against the wall, already spent.

I start chatting with another miner, who tells me his name is Ivan. “I’m Russian,” he jokes, before erupting into laughter.

I ask how he feels about our presence underground. “You are welcome,” he says. “You bring gifts. You bring coca leaves.”

There’s no avoiding the moral question of whether tourists are helping or exploiting the very miners they come to see. At the end of the guided tour, I ask the other people in my group—five twentysomething tourists from around the globe—how it felt to visit the mines. Hanna Michali, a tourist from Germany, tells me that “everyone” should see what is going on in Cerro Rico—and “how lucky we are compared to how hard others work,” she adds. Annabelle Brewer, a New Zealander, points out that tourism is a “big help” to people in the community, but she also feels uneasy about being in the mine. “It felt weird just going into someone’s workplace and taking photos.”

According to critics of Cerro Rico’s guided tours, too many visitors are coming to Potosí in search of extreme tourism—here, a sort of “danger tourism,” given the mountain’s real risks—without regard for how chasing such exotic experiences might sensationalize and demean the local culture. Julio Morales worked in Cerro Rico for three years before founding Greengo Tours, which leads tourists into the mines. He has grown more conflicted about his work over the years. He rails against the “stupid” tourists who, in search of thrills, will harass guides to take them to the mine’s more perilous areas. “They don’t care about the miners. They just want selfies.” Visitors to Cerro Rico, he adds, need to show respect for what happens there. “They are going to a real mine, where miners die.”

In 2019, Morales stopped leading tours, in part because he was shaken by a mining accident that killed four of his friends. “I have ghosts in my life,” he says. “That is why I want to change the system.” Morales says he and other activists have been lobbying for more government oversight of mining tourism. Among other things, Morales wants to limit tourists to just one mine considered to be safe, require better training for guides, and mandate that a fixed amount of tour proceeds go to social welfare programs that benefit the miners and their families. (As a goodwill gesture, tour companies advertise they donate around 13 to 15 percent of their proceeds to the cooperatives or social welfare programs, but advocates for the miners claim the percentage is much less.)

For his part, our tour guide Ticona says the trips serve an important educational purpose. “If we do not visit the mines, we will continue to consume electronic products without knowing and valuing the sacrifice they make to obtain the metals that are the basis of these products.” (Some of the metals extracted from Cerro Rico are used in circuit boards and computer chips, meaning the smartphone or laptop you’re using to read this article might contain a bit of the mountain’s minerals.) Other supporters of the tours point out that it sustains small local businesses and provides work other than mining for the people of Potosí to do. The miners, they add, are proud of their ability to persevere underground, and some enjoy teaching tourists about what their work looks like. “It is one thing to think theoretically about mining. It is another to see it,” says Ricardo Farinha, a Portuguese tourist who was also in my group. Farinha acknowledges having qualms about the “zoo”-like nature of the tours. “But I wanted to see the working conditions, so I put my morals aside.”

Every once in a while, a group of miners will strike it rich by discovering a high-grade vein. This is a dream that drives many workers at Cerro Rico. “The mine is like a lottery,” Morales says. “Today might be the day.” Yet today might also be the day that they are injured or killed in the course of their work, he adds. “You have to be crazy to work in the mines, with the conditions. But there are no other alternatives.”

Mark Dickinson Mark Dickinson has taught on three continents and traveled to more than seventy countries. Before beginning his career in the classroom eighteen years ago, he worked for almost a decade as both a television and newspaper reporter.

- Follow us on Twitter: @inthefray

- Comment on stories or like us on Facebook

- Subscribe to our free email newsletter

- Send us your writing, photography, or artwork

- Republish our Creative Commons-licensed content