Hiba Nisar was eighteen months old when she became the youngest casualty of the latest phase in the deadly, decades-long conflict in Kashmir. Last November, protesters clashed with Indian security forces outside her home in Kapran, a village in the south of the Muslim-majority state controlled by India but also claimed by Pakistan. As protesters pelted them with stones, Indian police fired tear gas, which began to seep into Hiba’s home. Hiba started to choke.

Her mother, Marsala Jan, grabbed her and opened the door, intent on getting her out of the smoke. “As I sneaked out, I heard a loud bang,” Jan recalls—the security forces had fired their shotguns. A spray of lead pellets ripped through the doorway. Jan had covered her daughter’s face with her hand, but a pellet went through her hand, she says, and into Hiba’s left eye.

Hiba was partially blinded. “Fate struck a terrible blow,” Jan says. “I held my child tight, but … I failed to protect her eye.”

Since 2010, Indian security forces have used pellet guns to deal with widespread protests in Kashmir, leading to the blinding, maiming, or killing of hundreds of people, according to human rights advocates and local medical personnel. While the term “pellet gun” brings to mind a children’s toy, the pellets—also known as birdshot—are metal and spray over a wide area. Most countries do not use them for crowd-control purposes because they cannot be aimed and thus cause indiscriminate injury.

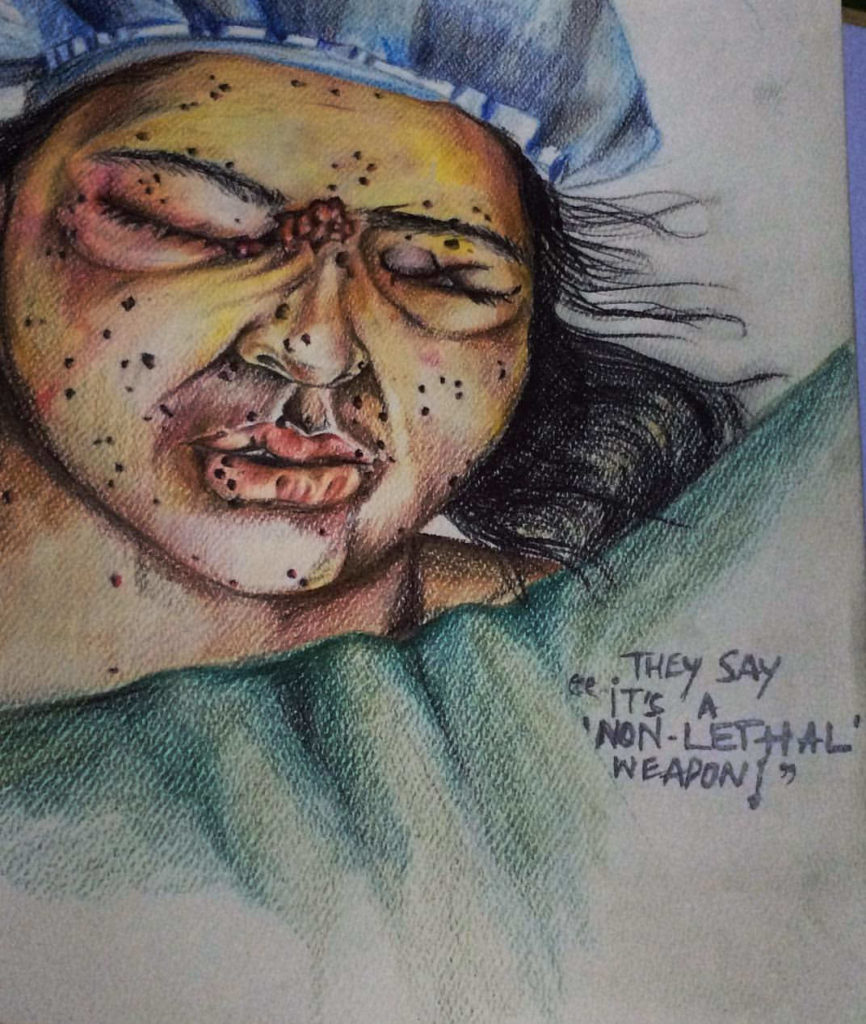

Furthermore, while touted as “non-lethal,” the projectiles can kill and mutilate. In Kashmir, seventeen people died in 2016 and 2017 after being hit with pellets, according to reports compiled by the Jammu and Kashmir Coalition of Civil Society (JKCC), a consortium of human rights organizations working in the state. Hospital records from Srinagar, the state capital, indicate that more than a thousand people have suffered eye injuries from pellets since 2016. A study earlier this year by researchers at Government Medical College in Srinagar found that 59 percent of those with pellet-related eye injuries ended up with permanent visual impairment, and 11 percent were completely blinded.

The long-running conflict in Kashmir continues to kill scores of people every year, with 108 security forces personnel, 120 militants, and forty-three civilians dying in the first half of this year alone, according to the JKCCS. In response to the international outcry over civilian deaths and maimings from pellets, Indian security officials have argued that they need to respond with deadlier forms of force because anti-government protesters use deadly force, including throwing stones. “There is an orchestrated campaign against pellet guns precisely because it is doing the work of effectively controlling the violent mob protests,” an unidentified senior security official in Kashmir told the Washington Post. “When there is a determined militant crowd hurling sharp stones at us and [they] break our helmets, shields and bones, then we need to act. Tear-gas shells are not very effective, because protesters use wet cloth to cover their eyes and are back in action in two minutes.”

But the use of pellet-firing shotguns in Kashmir has brought about an epidemic of “dead eyes”—blindings from the sprayed projectiles. In 2016, medical workers in Srinagar, the capital of the state of Jammu and Kashmir, were seeing so many of these injuries that they staged a protest, wearing gauze patches over one eye to raise awareness about the suffering caused by the Indian government’s use of the deadly ammunition.

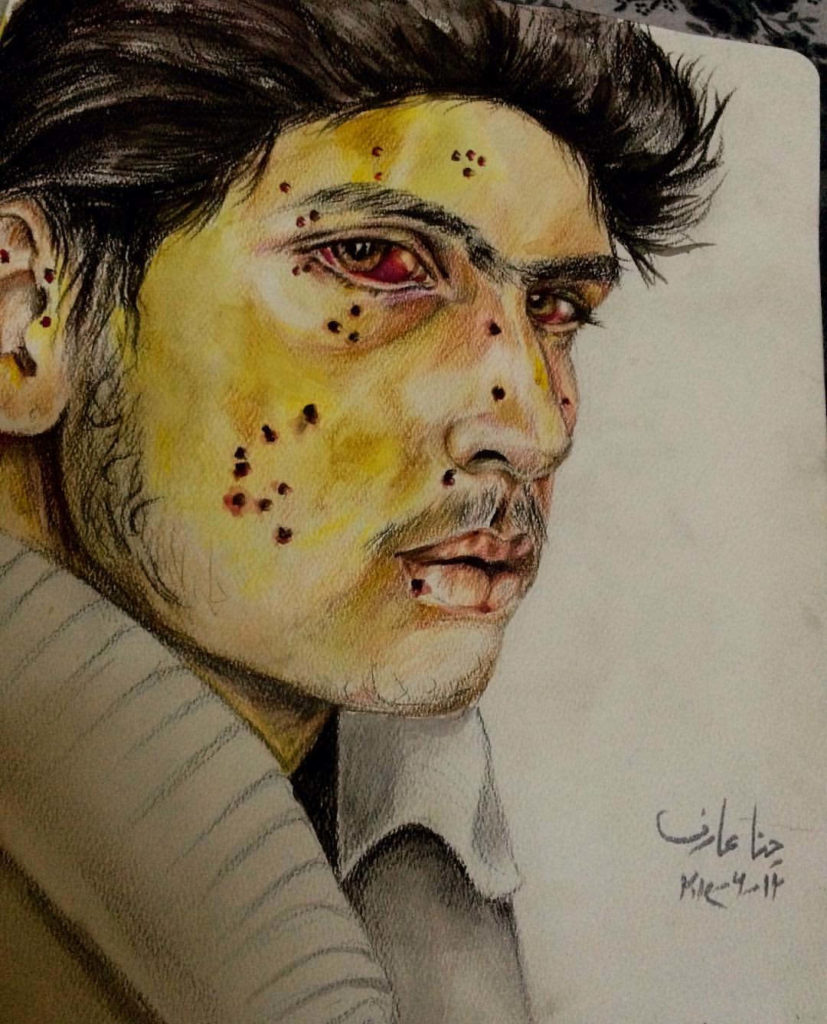

Danish Rajab was partially blinded after being shot during that year’s wave of protests in Srinagar. A soft-spoken man in his early twenties, Rajab says he regularly took part in anti-India demonstrations downtown, joining the throngs of young men who would throw stones at security forces. At one protest near his home in the city’s Jogi Lanker area, Rajab was running toward the crowd to join them when he heard a bang. “I felt a little warmth in my eye,” he says. “I looked down, and blood was pouring across my face and neck. The blood was coming from my left eye, and I wasn’t feeling any pain. People watching me from the alleys shouted that pellets had hit my face.” Rajab was rushed to the hospital. The operation to save his eye was excruciating, he says. Today, after raising money from his community to fund three expensive surgeries, Rajab can still only see blurry images from his wounded eye. He says he used to work as a salesman, but he could no longer continue with his job after he was injured.

In a 2017 report, the human rights organization Amnesty International documented eighty-eight cases of people blinded by pellet-firing shotguns used by the Jammu and Kashmir Police (JKP) and Central Reserve Police Force (CRPF) over the previous three years. It condemned the use of pellet guns in Kashmir as violating international human-rights standards on the use of force. “Authorities claim the pellet shotgun is not lethal, but the injuries and deaths caused by this cruel weapon bear testimony to how dangerous, inaccurate, and indiscriminate it is,” said Aakar Patel, the executive director of Amnesty International India, in a statement. “There is no proper way to use pellet-firing shotguns. It is irresponsible of authorities to continue the use of these shotguns despite being aware of the damage they do.”

In spite of the Indian government’s statements over the years that it would replace pellet guns with less dangerous forms of crowd control, “those promises have not been kept,” the report by Amnesty International concluded. Two years later, Indian security forces continue to use pellet-firing shotguns. In a May protest in Srinagar, for example, about sixty civilians were injured by pellet fire, according to hospital officials—ten critically.

While the blindings have become a graphic symbol of the violence in Kashmir, the larger issue, activists say, is the government repression that makes such injuries so common. As Arif, a student activist from Srinagar, puts it: “Indian forces find it justifiable to mow down civilians.” (The student, a graduate student from Kashmir University who asked that his last name not be used, was later arrested and is currently detained under a state law that permits authorities to hold suspects up to two years without a trial.)

According to the Jammu and Kashmir Coalition of Civil Society, civilian deaths from the state’s ongoing conflict spiked again in 2018. That year, 160 civilians died, the largest death toll since 2010. The group also says that between 2003 and 2017, eight children died from pellet injuries in Jammu and Kashmir, though another eight died from riot-control measures that are supposed to be less deadly than pellet guns: tear gas and “chili grenades” (a pepper-based weapon similar to tear gas), which can bring about asphyxiation.

After subsiding somewhat in recent months, violence in the area has surged again following a controversial government decision to revoke Jammu and Kashmir’s special status. On August 5, the administration of Indian prime minister Narendra Modi passed legislation in parliament to strip the state of its semi-autonomy and split it into two territories. Modi’s right-wing Bharatiya Janata Party, known for its Hindu nationalist policies, sees the move as a way of better integrating the conflict-ridden region. When the Modi administration announced the decision, it immediately imposed a curfew, sent in additional troops, and cut off phone and Internet service across the state. As protests have raged in the streets over the past month, authorities have released little information. According to government data acquired by the Reuters news service, however, security forces have so far arrested more than 3,800 people. About 1,200 individuals—among them, some prominent state leaders—are still being detained, and dozens more are being arrested every day, an Indian official told Reuters. Meanwhile, the communications blackout remains in place. After first denying that there had been any casualties because of the military lockdown, the government earlier this month confirmed five civilian deaths, which an Indian army official blamed on “terrorists, stone pelters, and puppets of Pakistan.”

In the past, the Indian government has called upon Kashmiri locals to stop “supporting the terrorists” by attacking Indian security forces as they conduct anti-militant operations. In a 2017 statement, Indian army chief Bipin Rawat in 2017 condemned the “local boys” who flock to the sites of gun battles in order to throw stones and help militants escape. “If they want to continue with the acts of terrorism, displaying flags of ISIS and Pakistan, then we will treat them as anti-national elements and go helter-skelter for them,” Rawat said. (The Islamic State, also known as ISIS, has supporters in Kashmir, and in May the extremist group declared it had established a “province” in the state—though experts have said ISIS is merely using such claims to motivate its dwindling base of support following its recent expulsion from Iraq and Syria.)

The conflict over Kashmir dates back to 1947, immediately following the subcontinent’s partition, when the Hindu ruler of the Muslim-majority state turned to India for protection after armed tribesmen from Pakistan’s North-West Frontier Province threatened his rule. India currently administers 45 percent of the territory that it and Pakistan both claim, with the remainder controlled by Pakistan and China. India and Pakistan have fought three wars over Kashmir, but neither has been able to claim the territory in its entirety.

India, the world’s largest democracy, has allowed Kashmiris to vote in elections. But widespread allegations of rigged elections and brazen meddling by New Delhi in the region’s governance has led many residents—particularly young Kashmiris—to lose faith in Indian democracy over the years.

The dissent reached a more dangerous pitch when armed revolt erupted in 1989. Pakistan backed the separatist movement, providing militants with weapons and funding and training fighters in Azad Kashmir, the western part of Kashmir that it controls. In response, the Indian government pursued brutal counterinsurgency measures, resulting in the deaths of more than 47,000 people—not including those who have disappeared amid the violence.

The latest phase of the conflict—marked by the widespread adoption of pellet guns by Indian security forces—can be traced to the Amarnath land row in 2008, when hundreds of thousands of people took to the streets in Hindu-dominated Jammu and Muslim-dominated Kashmir to either challenge or support a government decision to use public lands to facilitate a Hindu pilgrimage. The street fighting spiked again in the summer of 2016, after the killing of Burhan Wani, the popular twenty-two-year-old commander of the pro-Pakistani militant group Hizbul Mujahideen. Forty-five protesters and one police officer died and thousands were injured during the ensuing protests that swept the state of Jammu and Kashmir.

More recently, relations between the region’s residents and security forces have suffered due to the discovery of mass graves with the remains of an estimated 2,000 individuals allegedly “disappeared” by authorities, as well as accusations that security personnel have sexually harassed local women and men. These developments have added to a long history of alleged human rights abuses in India-controlled Kashmir, some of which are—decades later—still being investigated or litigated. Such atrocities inevitably occur, activists say, because of the impunity that Indian law provides to security officers when they operate within the conflict-ridden state. At the same time, government officials have cracked down on the civil liberties of Kashmiris. In addition to the state laws that allow them to detain suspected militants—including minors—without a trial, the authorities impose periodic curfews and have taken to throttling the Internet whenever a civilian or militant killing sparks renewed fears of protest.

The constant presence of armed Indian paramilitary troopers in Kashmir has brought about a collective feeling of “hopelessness” and an uncertainty about the future, says the Kashmiri poet Madhosh Balhami. “We can’t even be sure about what will happen tomorrow, leave aside the future,” says the fifty-three-year-old, whose real name is Ghulam Mohammad Bhat. Last year, separatist militants forced their way into his home in Balhama, seeking cover in a standoff with Indian troops. The poet and his family fled, but their house burned down in the firefight, destroying hundreds of pages of his poetry, he says. Nowadays, Balhami is pessimistic that India and Pakistan will ever negotiate peace. “Most people in Kashmir think both nations are after their own interest,” he says. “If this dispute was not resolved for seven decades, how can it be resolved [now]?”

One thing that has changed in recent years is the ability of Kashmiris to document the violence around them. After her injury, a photo of Hiba’s bloody face went viral, leading to a renewed wave of international criticism of India’s use of pellet guns in Kashmir. In May, the toddler was the focus of media attention after she and her family appeared at a demonstration in Srinagar. In another photo that appeared online, Hiba held a placard that read “India: Stop Blinding Kids.”

Social media has also played a role in channeling local anger at the Indian government. Militant leaders regularly share video and audio messages on these platforms. Those young Kashmiris who are not protesting on the streets may instead be posting comments critical of the India government on social media—and the authorities appear to be cracking down on such activities, in addition to harassing and jailing local journalists.

With every “horror” visited upon the residents of Kashmir, says twenty-nine-year-old local activist Ashraf Wani, the population becomes more resistant to Indian rule. Wani lost most of his sight in one eye after he was injured in the face and chest by pellets during a 2016 protest in the southern Pulwama region of Kashmir. Afterward, he and other injured Kashmiris formed the Pellets Welfare Trust, which helps raise money to pay for the treatment and rehabilitation of those wounded by the use of such weapons. According to his organization’s figures, more than a thousand Kashmiris have had their eyesight damaged by pellet guns. “Not all the victims were demonstrating,” he says. “Even then, no government has the right to blind civilians for taking part in protest.”

In addition to blinding victims, the pellets fired by Indian security forces can become permanently lodged in their bodies—including in their eyes—because the metal ammunition is too risky for surgeons to remove. With each cartridge containing five hundred pellets, the bodies of victims can be riddled with the lead balls—as vividly depicted in X-rays. Doctors are unsure about what long-term complications may arise from the presence of these foreign objects in people’s bodies.

The damage is not just physical, but also mental. Without their eyesight, many young Kashmiris can no longer pursue their educations or continue to work the jobs they once did. They often become socially secluded and deal with depression and anxiety, says Ashraf Ali, an associate professor at Jamia Millia Islamia who studies Kashmir youth.

“I am worthless,” says one man in his twenties who was blinded by a pellet gun after attending a protest in Srinagar. “It [would have been] better to be killed than live a life of a corpse.” The man, who asked not to be identified, said that his injury turned his life “upside-down.” He requires constant assistance to survive, and he continues to have nightmares about being chased by Indian security forces, he says. “Whenever I find any military personnel coming towards me, I shiver.”

- Follow us on Twitter: @inthefray

- Comment on stories or like us on Facebook

- Subscribe to our free email newsletter

- Send us your writing, photography, or artwork

- Republish our Creative Commons-licensed content