Imagine a Goodwill tucked inside an elementary school, with the energy of a Cairo airport gate. That’s the scene, on busy days, at IRIS, the refugee resettlement agency where I work in New Haven. The downstairs donation space overflows with coats; lamps stand over stacks of pots, pans, and bassinets. Upstairs, refugees from the Middle East and Africa bustle about the hallway with cups of tea and paperwork. Along the walls are world maps and local bus routes, kids’ drawings of airplanes and stars, flashcards for the US citizenship exam.

Working with refugees is unsettling sometimes. Knowing who survived genocide only to get hit by a car, who has trouble eating when he thinks about his mom not having food back home, whose sister tried to get to Europe on a raft—it undoes you sometimes.

Over the last two years, refugee resettlement work has gotten tougher. In 2017, President Trump’s “travel ban” blocked visitors and migrants from a number of Muslim-majority countries and temporarily halted the admission of refugees altogether. The US refugee resettlement program is now operating again, but the Trump administration has taken other, less publicized steps to undermine it—most recently, setting a record-low cap on admissions of just 30,000 refugees for 2019, less than a third of the annual average since 1980.

A few years ago, I got to know a thirty-two-year-old refugee named Kamal while he was trying to figure out how to bring his family to safety in the US. (To protect their privacy, the names of the refugees in this story have been changed.) Kamal is from the Darfur region of Sudan. Before I met people in his community, all I knew about Darfur was headlines of atrocity: “Sudan’s bloody stalemate,” “Sudan’s Department of Gang Rape,” “Darfur Wasn’t Saved.” The conflict started in 2003, when the Sudanese government retaliated against rebel groups by targeting Darfur tribes. Since then, government-backed militias have been massacring civilians and burning villages in the region. The genocide continues, even as global interest in Darfur has waned. About three million people have been displaced so far.

Kamal sought refuge in Chad, where United Nations officials determined his eligibility to resettle in the US. That was only the beginning of an arduous application process of getting fingerprinted for security screenings, submitting documents, and convincing US officials in interviews that he really had experienced persecution. Between each step there were months of waiting, with no indication when or if his application would ultimately be approved.

During the next two years, Kamal lived in the Breidjing Refugee Camp in Chad. Founded in 2004, the camp houses tens of thousands of Darfur refugees on an arid patch of land along the country’s eastern border with Sudan. Conditions are harsh, and even the water is rationed. While he waited, Kamal worked as a history teacher in the camp. He eventually met and married his wife Safa there.

In 2015, Kamal found out that his refugee visa had finally been approved. But because Kamal and Safa had started their resettlement applications before their marriage, they were considered separate cases, and Safa was not allowed to join her husband—even though she was now eight-weeks pregnant with their daughter Rama. They were told he could apply to bring her later, through the “follow-to-join program” that reunites refugees in the US with their spouses and children overseas.

Kamal was faced with a difficult choice. If he stayed in the refugee camp, his visa would expire, and he would have to start the process all over again. He and Safa could end up waiting ten years or more, with no guarantee that they would both get resettled in the US. If he went, they would be separated, but his wife and their baby might get their visas much sooner.

Kamal decided to go. He was assigned to IRIS, which was already working with a small community of Darfur refugees who had found a safe haven in New Haven.

After Kamal arrived in Connecticut, he applied to bring his wife and child to join him. After a sixteen-month process of background checks, fingerprinting, and DNA testing, they thought they were close. Safa had her last interview with the US Department of Homeland Security in January 2017.

Two weeks later, on the day before Rama’s first birthday, the White House issued its first travel ban.

Before 2017, Kamal and his family had been separated by a bureaucratic machine that moved slowly, but did move. After the first travel ban, they had no idea what was going to happen. Safa called Kamal crying. She and the baby were now in Cameroon—they needed to be close enough to an American embassy for any visa interviews. This was supposed to be the last step in their family reunification process, but the executive order had suddenly made it much harder for them to come to the US. She told Kamal she wanted to go back to Sudan. She hardly knew anyone in Cameroon, and she didn’t speak the language.

“Please wait,” Kamal told her. It was too dangerous to go back.

One day, Kamal’s friend Ali shows me a home video from Darfur. In it, Ali’s brother is playing a stringed instrument made of tin, sitting next to a man in a suit singing. The people gathered around are standing and clapping along. Someone starts jumping. Another leaps up, and then another. They swing their arms and up they go, each time like a geyser—heels to the height of where their knees were, and somehow synchronized.

“I love this jump dance!” I say. “What’s it called?”

“Masalit.” It’s the name of their tribe and their native language.

“Darfur is the most beautiful part of Sudan,” Ali tells me. “On Fridays, you wash all the clothes and hang them outside to dry. You leave the doors open so the angels can come inside.”

Kamal’s six-year-old nephew Ammar has also resettled in Connecticut. Ammar has never been to their homeland, a lake-filled part of Darfur in Western Sudan. Like Rama, he was born in the Breidjing Refugee Camp. In 2015, Ammar came to the US with his parents, siblings, and their dad’s brother, Uncle Kamal. At the time he was just a toddler. When I first met them at IRIS, he was hiding behind his parents’ legs.

Sometimes Kamal shows Ammar videos of Masalit celebrations on YouTube: people gathered under the trees around a singer or two, jumping to the music. “Try to do this,” Kamal tells him. “This is your home song.” Sometimes Ammar dances along, jumping as high as he can.

About a month before the first travel ban, Sudanese community leaders invite me to what they call a welcome party, a celebration they are throwing for a group of refugees from their home region who arrived in New Haven the year before.

I see Kamal at the party. Still waiting for word on his family’s visas, he has kept busy with his work as a landscaper. (While refugees can receive temporary financial assistance from the government, it is not enough to cover their expenses. Employable adults like Kamal work long days to make ends meet.) Sitting next to him is his nephew Ammar. The child is wearing a button-up shirt with a silver suit vest, looking askance at a platter of watermelon in the middle of the table. When I sit down, he asks, “Do you have ice cream?”

“No,” I tell him. “I wish I did.”

“Do you have a car?” he asks.

“No, but I have a bicycle.”

“Then can we go get ice cream?” Before I can explain to him why I can’t take him downtown on my bike, he’s already talking to his uncle about something else.

I think for a moment about how much Ammar has changed since I first met him two years ago. Then, he was a little boy frightened about meeting strangers in a strange land. Now, he’s a kid who can get up to some mischief on the playground, who climbs jungle gyms and isn’t afraid to go down the slide, who asks you over and over on the swing set to push him high.

Later, Kamal shows me a picture of Safa holding baby Rama. “Since I left,” he says, “my heart has been thinking [of] my wife.” They will talk—across the Atlantic and half of Africa—through a video chat app. That’s how Kamal has watched their baby Rama grow—her first tooth, her first word. “Somehow, she knows me,” he tells me. She’s started to say “Baba”—Dad—to his picture on her mom’s phone, to the hand waving at her on the screen. She’s started to wave back.

Ammar will sometimes talk with his aunt Safa and little cousin Rama when they do a chat. Sometimes he shows them the food he is about to eat and asks, “What do you eat there?” Sometimes he asks, “Why didn’t you come here?”

Back at the welcome party, the celebration has turned into a dance-off. “Are you going to do the jump dance?” I ask Kamal.

He shakes his head. He isn’t in the mood to dance while his wife and child are still separated from him. “I’ll jump when I see them,” he says.

As defined by international law, refugees are people who have fled their homelands and undergone an extensive interview and verification process with UN officials to determine that they have a “well-founded fear of persecution” in their countries of origin. The UN refers the most vulnerable refugees to countries where they can apply to resettle. Less than 1 percent of the world’s twenty-five million refugees are granted resettlement.

The US used to be a global leader in offering safe haven to those refugees at greatest risk: individuals fleeing religious persecution in Myanmar, insurgency in Somalia, torture in Eritrea, ethnic cleansing in the Democratic Republic of Congo and Sudan, the wars in Syria, Iraq, and Afghanistan. That changed during President Trump’s first year in office. With a spate of executive orders, he began dismantling the US refugee resettlement program, cutting the number of refugees approved for resettlement here from 85,000 in 2016 to 33,000 in 2017—a larger year-to-year reduction than in any other country.

The Trump administration’s efforts to restrict travel from several Muslim-majority countries faced more pushback. Federal courts quickly blocked the first travel ban. The White House issued another ban two months later, which was again halted by federal judges.

The US Supreme Court ultimately upheld a third version of the travel ban in June, but the resistance in the courts made all the difference for Kamal’s family. It was during that brief legal opening after a federal court suspended the second travel ban that Safa and Rama received their visas. The family would finally reunite in America.

Kamal was at work when he got the good news. For the rest of that day, he couldn’t concentrate on the azalea bushes he was trimming. All he could do was sing.

I wait with Kamal on the day Safa and Rama arrive. A driver is supposed to bring them from JFK Airport to the refugee agency in New Haven—ETA 3:30 p.m. Kamal shows up at 2:30, in a cobalt-blue suit and wing-tipped shoes. We wait, with a car seat and a stuffed purple dinosaur with sparkly eyes, for the daughter he’s never met in person.

At 3:22, we go outside. I start to get that stars-in-your-heart feeling—when you’re so excited and nervous it feels as if something is leaping inside of you. You can’t bear to wait, yet you’re not ready.

Some coworkers and refugees gather outside to wait with us. A van pulls up, and I spot a young African woman and baby in back. The realization sweeps through the crowd. Some people start ululating. Surprised, I hear myself joining in. It brings to my mind Mary Oliver’s poem about whale watching: the moment you see the surface of the water break, you feel the breach inside of you; you hear whooping, and you realize it is you.

Kamal hugs his wife and attempts to hold his daughter. She starts crying. He tries to comfort her, telling her soothingly that he’s her “Baba.” She continues to cry. Eventually, he steps back to let his wife and another mom strap the baby into the car seat. Then, he gives her the purple dinosaur.

I see the family at IRIS three months later. Safa and Kamal have come to fill out W-2s for cleaning jobs. They’ve brought Rama, who wears a pink dress and Velcro sneakers with characters from the Despicable Me movies on the sides. (The shoes are hand-me-downs from Ammar.) We try to keep Rama entertained with a snack cake, a stuffed elephant, and toddler blocks, but she seems more interested in what her dad is up to. While he is making himself a cup of coffee, she tugs at his pants leg and points at another cup she wants to play with. “Baba,” she says, gesturing.

“She’s gotten used to you,” I say.

“Yes,” he says. “And she is starting to talk in English.” As if to prove his point, Kamal squats down and says to her, “High-five!” She taps her little hand on his.

Every day Rama plays with Ammar and her other cousins when they get home from school, the family tells me. By the way she bops around, even more buoyant than most kids her age, I can tell she’ll be good at the jump-dance someday.

This seems like a happy ending, but it’s not. Kamal’s mother was shot and killed in a militia attack on her village in Darfur last year. Kamal and his brother, Ammar’s dad, didn’t go home for the funeral. As Muslim refugees, they might not have been able to get back into the US, even though they’re legal residents here. Instead, they did a memorial service for their mother at their apartment in New Haven. The Sudanese community gathered there to pray and read the Qur’an together.

The last time I see Kamal at IRIS, he wants to know how he can apply to bring his younger brothers and sister in Darfur to America. Since their mother died, an adult sister has been taking care of the kids.

I don’t want to dash his hopes, but the Trump administration is making it harder and harder for immigrants to bring family members to the US. The president’s rhetoric against “chain migration” has coincided with both a drastic reduction in the number of visas issued to family members overseas, as well as longer wait times for them. In 2018, the number of family-based visa approvals plummeted to its lowest level in over a decade, according to Reuters.

Perhaps the younger siblings should follow Kamal’s path instead—seeking refugee status and resettlement referrals from the UN in Chad. But it’s unclear whether they would have a better shot at coming to the US if they pursued this option rather than a family-based visa, given all the restrictions that the Trump administration has placed on refugee resettlement as well. Since President Trump took office, refugee admissions of Muslims have dropped by 91 percent, according to the Cato Institute. (In September, Sudan—one of the countries covered by the original travel ban—was removed from the administration’s list, but seven countries still remain on it.)

In addition to the travel bans and the cap on refugee admissions, the federal government now requires refugee applicants to provide phone numbers and addresses for all relatives in their family tree—information most don’t have, because their families were scattered under duress. The administration calls such measures “extreme vetting,” but the US already had the most rigorous refugee screening process in the world, involving the Federal Bureau of Investigation, the Central Intelligence Agency, and the Department of Homeland Security.

Furthermore, the infrastructure of refugee resettlement is so impaired that it takes longer to process any refugees who do meet the requirements. In response to the barrage of bans since 2017, refugee processing centers overseas have closed offices and laid off or relocated staff. Many agencies that help refugees once they arrive in the US are having to shut down.

I don’t say any of this to Kamal. He knows much better than I do what refugees have to go through for a chance at reaching a safe place they can stay. I get him the form he needs to request legal help with his family’s case. Together we go over a chart that asks for information about the family members he wants to bring to the US. He writes down their names and birth dates, where they were born, and where they live now.

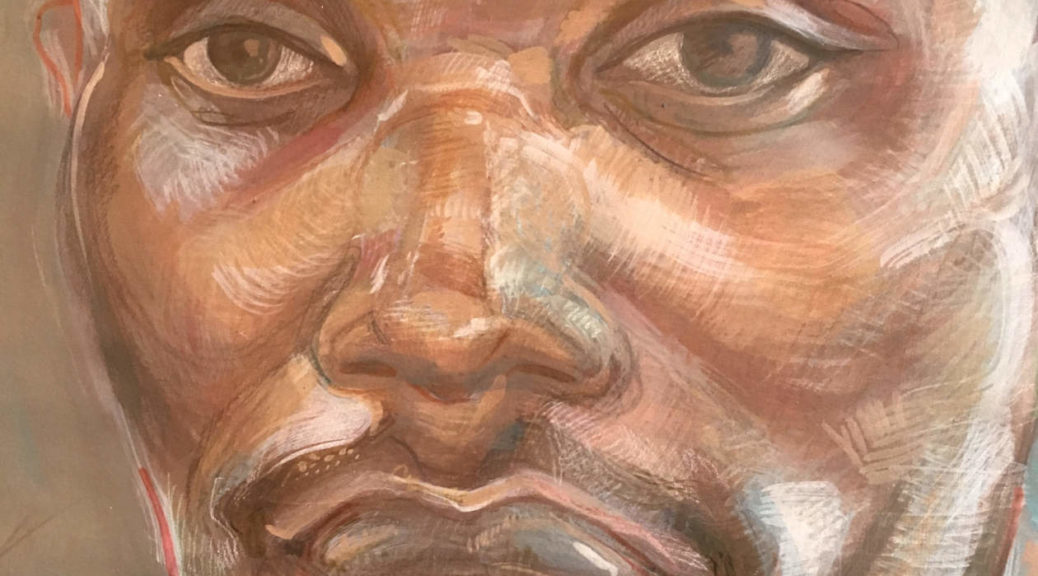

After finishing the form, Kamal shows me pictures of his younger siblings. He points out his little sister in a group photo from her school. Five girls are standing together, wearing purplish-pink hijabs that match their uniforms. The expressions on their faces are striking. They are not just cute school girls posing for a portrait. Their eyes have a somber, piercing look. I think about all the troubles they’ve seen, and all the ways they’ve had to learn—too early—to protect themselves.

Then I think of the picture that I’ve taped on the wall beside my desk. It’s Ammar standing in the grass at a city park, wearing a shirt with a big-mouthed cheese-and-pepperoni slice on front that says “You want a pizza me!” He has a cherubic face—but a mischievous spark in his eyes.

Ammar’s cousins in Darfur only have a remote chance of being able to come here someday. But I keep hoping for good news. Maybe policies will change to make America a place of refuge again. Maybe the cousins will be lucky. Maybe then we’ll have another welcome party, and I’ll get to see all the kids jump-dancing in light-up sneakers, late into the night.

Ashley Makar Ashley Makar is the community liaison at Integrated Refugee & Immigrant Services (IRIS). Her writing has appeared in the Washington Post, Tablet, and Killing the Buddha.

- Follow us on Twitter: @inthefray

- Comment on stories or like us on Facebook

- Subscribe to our free email newsletter

- Send us your writing, photography, or artwork

- Republish our Creative Commons-licensed content