For nearly three hundred years, white settlers and American Indians engaged in mutually destructive warfare. The bloodshed followed the path of white Western migration—from the first English settlement in Jamestown, Virginia, where colonists coming ashore in 1607 were met with a volley of the Powhatan’s arrows, to far Western lands like the Montana territory, where General Custer and his soldiers made their last stand in 1876, overrun by Lakota, Northern Cheyenne, and Arapaho warriors on the banks of the Little Bighorn River.

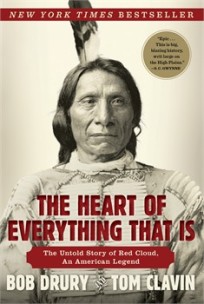

Their stunning victory in the Battle of the Little Bighorn immortalized the names of great Indian chiefs like Sitting Bull and Crazy Horse. But in The Heart of Everything That Is, Bob Drury and Tom Clavin make the case that a relatively obscure Oglala Lakota chief called Red Cloud was actually the era’s most fearsome and effective Indian leader, a brilliant tactician of guerrilla warfare who a decade before Little Bighorn had beaten the US Army in a bloody conflict known as “Red Cloud’s War.”

During the grim years of resistance leading up to the war, Red Cloud brought together several of the warring factions of the Sioux nation into an unprecedented alliance. In what is now Wyoming, he rallied an army of more than two thousand Lakota, Northern Cheyenne, and Arapaho fighters. And under his leadership, Indian forces successfully (if temporarily) swept US forces out of the prized lands that the whites called the Powder River Country and the Sioux called Paha Sapa—”The Heart of Everything That Is.”

Much of this story has never been told before. Drury and Clavin are among the first historians to draw from Red Cloud’s little-known autobiography. Excerpts of the manuscript “Life of Red Cloud” appeared in a South Dakota magazine in 1895, yet a complete version of the memoir remained unpublished. It withered away in the archives of the Nebraska State Historical Society until the 1990s, when historian R. Eli Paul rediscovered the manuscript, validated its authenticity, and published it. The autobiography has given scholars a deeper appreciation for Red Cloud’s unique talents—as a savvy war leader who outsmarted and outfought the US military, and as a determined peacemaker who built pragmatic coalitions among the tribes.

Born in 1821, Red Cloud grew up among the powerful Oglala Lakota, one of the seven sub-tribes of the Lakota people. (The Lakota, Nakota, and Dakota tribes together comprise the Sioux nation.) When he was four, his father—a Brule Lakota chief named Lone Man—died of alcoholism, leaving Red Cloud a fatherless boy. Under Sioux traditions, Lone Man’s death was not an honorable one sustained in battle or on the hunt, and the shame clung to his son, hindering his prospects among the Brule. Fortunately, two venerated maternal uncles welcomed Red Cloud, his mother, and his two siblings into the Oglala band. They demonstrated keen interest in Red Cloud’s upbringing and taught him tribal traditions. Despite the commanding influence of this bloodline, Red Cloud would shoulder the stigma his father had brought upon the family for the rest of his life.

The disgrace, the authors suggest, pushed the young Red Cloud to prove his valor and strength of character. He quickly distinguished himself as a warrior in the Lakota battles with neighboring tribes like the Crows, Pawnee, and Kiowa. At sixteen, he made his first kill during a raid on the Pawnee. He returned to camp a hero, lofting his victim’s scalp to his tribe’s approving ululations.

As his kills multiplied, Red Cloud’s courage and fighting skills became legendary—as did his mercilessness. Soon anecdotes began to circulate about the delight he took in terrorizing his enemies. During one battle, Red Cloud jumped into a river to save a Ute attacker from drowning, only to drag him to the water’s edge, press the knife into him, and scalp him. On another occasion, Red Cloud captured a marauding Blackfoot and then promised him he could return to his tribe safely—if he could withstand being scalped without making a sound. The Blackfoot survived the torture. Before letting him go, Red Cloud demanded that the brave tell his tribe who had mutilated him. Red Cloud coveted the scalps of his enemies, Drury and Clavin write, but it was more important to him that “rival tribes learned, and feared, his name.”

In detailing the ruthlessness of Red Cloud’s actions, the authors avoid both hero worship and censure. They use a wide array of sources to portray him as a product of his place and time—a boy hardened by his family’s bereavement, a man provoked by the deceit and destruction his long-suffering people witnessed.

By 1866, the tribes of the Powder River Country had grown tired of the US government’s broken treaties. Each time they signed pieces of paper that stated further encroachments on Indian lands would cease, and each time the promises, as the authors put it, “lasted about as long as it took for the ink to dry.” Red Cloud and his people came to the conclusion that it was only a matter of time before the white man would try to occupy all of Paha Sapa, for when had they ever known him to be content with the lands he already possessed?

Red Cloud reasoned that armed resistance by an intertribal coalition of warriors was the only recourse. Joined by Northern Cheyenne allies, he persuaded the fractious Lakota, traditionally neutral Arapaho, and rival Shoshones and Nez Percé to unite as one and direct their hatred of the white man toward a defense of their homeland. Paha Sapa was their birthright, Red Cloud reminded his recruits. It was worth the fight and, if necessary, the sacrifice of their lives.

In May 1866, Red Cloud attended one of his last treaty-signing ceremonies—this time, at Fort Laramie in Wyoming. As the leaders on both sides inked yet another piece of paper, the Lakota chief made a promise of his own. Addressing the US commander, Colonel Henry Beebee Carrington, he pledged, “As long as I live, I will fight you for the last hunting grounds.”

Red Cloud kept his promise.

Seven months later, the Oglala and their tribal allies ambushed a detachment of US soldiers just outside Fort Phil Kearny, Carrington’s base in the Wyoming hills. Mounted Cheyenne stampeded from the surrounding woods, while Lakota and Arapaho rushed out on foot from the tall prairie grass. The Indians enveloped the soldiers and hacked at them with knives and tomahawks in an “orgy of butchery.” The soldiers fired their weapons, yet there was little time to reload. When the fighting stopped forty-five minutes later, eighty-one soldiers were dead. It was the US Army’s worst military defeat to date on the Great Plains—a body count that would only be exceeded when Custer blundered Into the Battle of the Little Bighorn ten years later.

During the war that followed, Red Cloud unleashed on his American enemies the very same hit-and-run attacks that they had used so successfully against British Redcoats a century earlier. While the Indians’ weapons were no match for the US Army’s state-of-the-art munitions, Red Cloud’s fast-moving forces confounded and unnerved the Americans. Unlike other Indian commanders, he was strategic and disciplined, following up on his victories and applying continual pressure. “In Red Cloud the Indians had finally found a war chief who could coordinate and sustain an effective military campaign,” Drury and Clavin write.

The authors humanize the unfolding conflict with the stories of individuals on either side of the battle lines. The memoirs of Carrington’s two wives provide some insight on how white military officers understood the war. Drury and Clavin also present the accounts of Ridgway Glover, a flamboyant adventure seeker who believed himself—tragically—to be invulnerable, and the mountain man Jim Bridger, one of the best scouts on the frontier, whose affection for Indians did not extend to the Sioux. On the Indian side, notable war leaders make appearances in the book. In one vividly rendered scene, Crazy Horse, Red Cloud’s fierce but reckless protégé, heads out on his horse to coax Americans soldiers into battle.

Overextended and unwilling to sacrifice more of its soldiers, the US government eventually decided to negotiate with Red Cloud and his tribal alliance. Red Cloud demanded that his enemies close the Bozeman Trail, a recently blazed trade route that bisected the Powder River Country from Fort Laramie to Virginia City, Montana, and abandon the three forts established along its route. He would accept nothing less than full withdrawal, and in May 1868, the US government conceded. Later that year, Red Cloud traveled to Fort Laramie to sign yet another treaty, one that returned Paha Sapa to him and his people. He had won back the Sioux hunting grounds, and it was, the authors write, the proudest moment of Red Cloud’s life.

Yet his people’s repossession of the Powder River Country was short-lived. After the completion of the Union Pacific Railroad in southern Wyoming in 1869, white settlers swarmed the region and hunters decimated the buffalo. Red Cloud recognized that the Lakota way of life was ending. He traveled to Washington in 1872 and persuaded US officials to set aside territory for an Indian agency in northwestern Nebraska. Red Cloud relocated there that year. Soon after, he declared, “I shall not go to war anymore with whites.”

Two years later, gold was discovered in Paha Sapa. The US government violated their treaty and allowed miners and prospectors to occupy Indian land. It then announced that the Indians would be forced onto reservations, and this time, the US Army was prepared to root out any opposition.

Sitting Bull and Crazy Horse plotted retaliation and lobbied Red Cloud to join their fight. He demurred. By then Red Cloud had come to the conclusion that taking on the US Army was futile. During his visits to Washington, he had been struck by how many people and how much weaponry the United States had at its disposal, and he realized that all this power would be used to annihilate his people. Red Cloud saw no point in rallying his coalition to engage in a campaign of attrition. “Red Cloud had not changed,” the authors write, “but he had adapted, and unlike Sitting Bull and Crazy Horse and the others who fought on, he had seen his people’s future. He understood that he, and they, had been overcome by historical forces.”

The Battle of the Little Bighorn proved a military success, yet victory was fleeting. Sitting Bull escaped to Canada, Crazy Horse was captured and killed, and the Indians, facing starvation, retreated to the reservations. In 1878, Red Cloud himself made his last move, to the Pine Ridge Reservation in South Dakota. From there, he remained the political and spiritual leader of the Oglala Lakota. He fought US government officials with his words, demanding fair treatment and needed resources for his people. But he did not forget what he, and his people, had lost. “The white man made me a lot of promises, and they kept only one,” he once said. “They promised to take my land, and they took it.”

In 1909, at the age of eighty-seven, the old Lakota warrior Red Cloud died in his sleep.

After their deaths, legends grew around Indian leaders like Sitting Bull and Crazy Horse, who defied the US government only to be murdered off the battlefield. “Red Cloud may have been more feared than either,” Drury and Clavin write, “but it did not benefit his historical or popular reputation that the majority of his victorious raids, fights, and battles took place against fellow Indians and went, for the most part, unrecorded.” And when Red Cloud did face the US Army, they add, “in most of these cases none were left alive to testify to his military prowess.” If history is written by the victors, Red Cloud was a vengeful vision that the winning side was happy to forget.

Amy O'Loughlin Amy O’Loughlin is a freelance writer and book reviewer whose work has appeared in American History, World War II, ForeWord Reviews, USARiseUp, and other publications. She blogs at Off the Bookshelf.

- Follow us on Twitter: @inthefray

- Comment on stories or like us on Facebook

- Subscribe to our free email newsletter

- Send us your writing, photography, or artwork

- Republish our Creative Commons-licensed content