Amy Wilentz first visited Haiti in 1986, when she was a writer for Time magazine and the ousting of dictator Jean-Claude “Baby Doc” Duvalier was underway. Admittedly, Wilentz was not the type of foreign correspondent who traveled from war zone to war zone, or from one uprising to the next in pursuit of a grand and dramatic news event. Rather, Wilentz’s journalistic demeanor ran more along the lines of observational witness; she was a spectator of all that surrounded her, and sparked her imagination and curiosity.

Yet, when it came to Haiti, there was something “eternal” about the country that called to Wilentz. She had read The Comedians, Graham Greene’s 1966 novel about the reign of Jean-Claude’s father, François “Papa Doc” Duvalier, and scenes from the book remained etched in her mind.

Elected president in 1957, Papa Doc Duvalier is one of history’s most unforgettable political figures. His fourteen-year reign was the longest and most brutal in Haiti’s history. To quash political dissent, and protect himself from being overthrown, Duvalier created the Tonton Macoute, a personal police force that terrorized citizens and assassinated anyone Duvalier thought was a threat. In 1971, when Jean-Claude succeeded his father as president, Duvalier-style despotism continued.

From her office in Manhattan, Wilentz perused the daily news written by Haitian exiles in the 1980s, which heralded Baby Doc’s impending departure from power. Wilentz felt an impulse to witness the end of the Duvalier era. Plus, she wanted a firsthand look at the Tonton Macoute, which was still in use by Baby Doc. With guns tucked into their waistlines and hats lowered over their sunglasses, the Tonton Macoute haughtily prowled Haiti’s streets to search for so-called troublemakers.

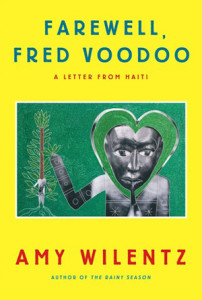

Thus began Wilentz’s love affair with Haiti. Her decades-long relationship with “La Perle des Antilles” (“The Pearl of the Caribbean”) has been anything but straightforward, simple, effortless, or predictable. In her first book about Haiti, The Rainy Season, Wilentz chronicled a nation and a people that were oppressed by the Duvalier regimes’ terror and totalitarianism. In her latest book, Farewell, Fred Voodoo, a deeply personal narrative about post-earthquake Haiti and Wilentz’s connection to the place, she revisits the country to listen to Haitians and recount her astute, unvarnished impressions.

Hello, Fred Voodoo

Wilentz’s experiences on her initial trip to Haiti commenced her “Haitian education,” and introduced her to stereotypes of Haitians invented by the outside world. One stereotype that persisted was the idea of “Fred Voodoo” — a dismissive term used by many reporters to refer to the ordinary Haitian man (or woman) on the street. “Fred Voodoo” could be a presidential candidate, a market lady, a renowned academic, a taxi driver, an unwed mother, or an Army general.

In 1986, Wilentz routinely interviewed Haitians, who told her what it was like to not have enough food for themselves and their families, and who wondered what it was like to live in a real house, not a shantytown shack. They discussed what it would be like to live freely and vote openly for a president who cares about ordinary Haitians and their suffering. They talked about democracy.

That was in 1986.

In 2010, after the 7.0-magnitude earthquake struck, many Haitians Wilentz interviewed still said a lot of the same things. Although this time they added more details of death and dying, blood, pandemonium, loss, amputation, starvation, and fear.

Returning to Haiti almost didn’t happen for Wilentz. She knew an abundance of international relief groups with “their money [and] their development résumés” would descend on a nation that already had more than ten thousand aid organizations in operation before the earthquake. She wasn’t sure she could tolerate a “salvation fantasy” from the international community, in which well-intentioned, post-disaster relief workers insist their presence would solve Haiti’s unmanageable, centuries-old troubles. Exasperated by the media’s reductionist portrayals of Haitians in despair — which she calls “the objectification of the Haitians’ victimization” — Wilentz wondered if she could “bear to watch the difficult lives of most Haitians rendered even more unbearable by this dreadful event.”

But she could not stay away. Within two weeks of the earthquake, Wilentz was back in Haiti for what may have been her thirtieth or fortieth visit. (She lost count after so many years.) The experience was consequential. She explains:

This book in your hands, then, is my attempt to put Haiti back together again for myself, to understand why all the simplest hopes and dreams of the men and women [that outsiders] call Fred Voodoo have been abandoned, and to stack the pieces flung apart by the earthquake back up into some semblance of the real country. I wanted to figure out, after so many attempts by so many to uphold democracy, why Fred and all his brothers and sisters have become, in our eyes at least, mere victims, to be counted up on one ledger or another as interesting statistics, casualties of dictatorship, of poverty, of disaster, of outside interference, of neglect, of history — of whatever you want to point a finger at — rather than as active commanders of their own destiny.

“Nothing You See Is What It Seems to Be.”

The long-standing misapprehension about Haiti and Haitian identity has everything to do with the country’s history, religion, culture, isolation, and relationship to the United States. As Wilentz discusses in great detail, and with keen insight: “[Haiti] defies categorization.… It’s eccentric and unexpected. At every corner, in every conversation, with every new event, Haiti makes you think, it challenges you.”

One of the many indeterminable stereotypes about Haitians is that “ninety percent of Haitians are Catholics, and one hundred percent are voudouisant, or voodoo worshippers.” Wilentz attended several voodoo ceremonies, during which various African gods were worshiped and spirit possession occurred. At the end of these “stunningly theatrical and participatory” services, she wondered whether Haitians really believe in voodoo, or if its practice is more tradition than conviction.

Wilentz knows this question is formalistic, and the answer is as enigmatic as the country itself. “Tou sa ou we, se pa sa,” a Haitian proverb warns. It translates to: “Nothing you see is what it seems to be.” Still, Wilentz doesn’t sit back and leave a gap in her analysis. She delves deeply into voodoo’s cultural importance.

“For most Haitians at a ceremony,” Wilentz asserts, “this is community, escape, entertainment, and as much transcendence as is allowed to them. For others, the ceremony represents Haitian patrimony and inheritance, and they take pride in it even when they have little or no religious belief.… This is a culture that values theater and a certain degree of artifice, even a great degree. Artifice and duplicity were natural and necessary survival methods during slavery.… How much of what the white man sees in Haiti is specifically a show for the white man to see — and this not just in terms of voodoo ceremonies, and not just today?”

Although an answer is unattainable, a look at Haitian history is instructive. In 1804, after obtaining freedom from France in the only successful slave-led revolution in history, Haiti became the first independent black nation in the Western world, but its legitimacy was suspect because it was ruled by descendants of slaves. After wresting power and prosperity from a European colonial power, Haiti was regarded by many as a nation that “never really had the right to exist.” As Frederick Douglass said in a speech at the 1893 Chicago World’s Fair, “We have not yet forgiven Haiti for being black.”

Haiti is much like the U.S. and France, countries whose histories cite revolution as a defining force that established sovereignty and national identity. Haiti’s revolutionary forefathers — Henri Christophe, Toussaint Louverture, Jean-Jacques Dessalines — maintain a presence in many Haitians’ minds similar to that of George Washington and Thomas Jefferson for Americans. Folklore has it that Dessalines “ripped the white stripe from the French tricolore in order to create the new red and blue Haitian flag, [sending] the message [that] the white man will have nothing to do with [Haitians’] destiny.”

It wasn’t to be.

For more than a century, France forced Haiti to pay reparations for the loss of the slave economy, while the slaveholding U.S. imposed a burdensome embargo that crippled the fledgling nation’s integration into the world economy. The U.S. occupied Haiti from 1915 to 1934, and it has meddled in the country’s affairs ever since.

Wilentz explains that, for almost all of the twentieth century, only U.S.-approved Haitians were allowed to become president in Haiti. She also cites a U.S.-led military intervention in 1994, Operation Uphold Democracy, that re-imposed President Jean-Bertrand Aristide. (Aristide had been overthrown by the Haitian Army just three years before the U.S. intervention.)

“I cannot recall another U.S. military deployment that performed regime change by reinstating an unseated leader,” Wilentz writes.”But Haiti is always singular, and so is America’s long, torrid relationship with it.”

Wilentz continues:

How Haiti works in general has historically had more to do with foreigners than is the case in most other countries, and this has never been so obvious as in the post-earthquake era. With so many coming down to assist in relief and reconstruction, so much of it concentrated in the capital, it has sometimes felt as though the country is being taken over by a new occupation, by a different kind of army.…

Rather than disrupting old ways of thinking about Haiti, the earthquake allowed many commentators, political analysts, and columnists to restate what they’d always imagined to be true about the world’s first black republic. The white Western world has a tendency, when confronted by Haiti’s intractable problems, to fall back on easy stereotypes and a deep-rooted, unconscious racism that suggests to them that this is all “depressing” and “hopeless,” and that somehow all the problems are the fault of this irresponsible, ungovernable people, with their weird old African customs and religion. It’s all Fred Voodoo’s fault.

But in fact, this depression and hopelessness come from “experts” who don’t understand Haiti, don’t acknowledge its strengths (and don’t know them), don’t get its culture or are philosophically opposed to what they assume its culture is, and don’t know its history in any meaningful way.

Despite billions of dollars in aid that flowed into Haiti, and thousands of relief workers who donated their time, it’s no secret that the country remains in disrepair. Wilentz is unsparing in her criticism of the failures of the international community and the Haitian government, and her writing on their dereliction is superb. She is unafraid to ask whether it is worth continuing to provide humanitarian assistance to a “kleptocratic” country that lacks a “functioning government that works for the people.”

Two Westerners who receive indisputable praise from Wilentz for “getting Haiti” are Megan Coffee, a doctor who cares for tuberculosis patients at her perpetually under-resourced Port-au-Prince clinic, and actor Sean Penn, who ran a refugee camp and moved refugees to real housing within days of the earthquake.

In the end, the most profound and perplexing question Wilentz asks, and tries to answer, is: “All the outsiders who come to Haiti, and come again, and never absolutely leave … what is it they get out of Haiti? This is the mystery I was trying to solve, after all. What do I get out of Haiti?”

At this point, Farewell, Fred Voodoo comes full circle. Wilentz’s love affair continues, yet it is changed. Indeed, Wilentz is changed. After “years of being schooled by Haiti,” she realizes the lessons have exacted an emotional toll.

“This book is … what I’m doing to relieve the pain,” she confides. “Putting down these marks across my computer screen: I can feel the release.… Yet what I’ve done in Haiti, what I’ve achieved with marks on paper, I cannot help but feel is useless, especially in the wake of this terrible disaster.”

Is Farewell, Fred Voodoo Wilentz’s goodbye letter to Haiti? For both her readers and a country that has been misunderstood for so long, I hope it is not so.

Amy O'Loughlin Amy O’Loughlin is a freelance writer and book reviewer whose work has appeared in American History, World War II, ForeWord Reviews, USARiseUp, and other publications. She blogs at Off the Bookshelf.

- Follow us on Twitter: @inthefray

- Comment on stories or like us on Facebook

- Subscribe to our free email newsletter

- Send us your writing, photography, or artwork

- Republish our Creative Commons-licensed content