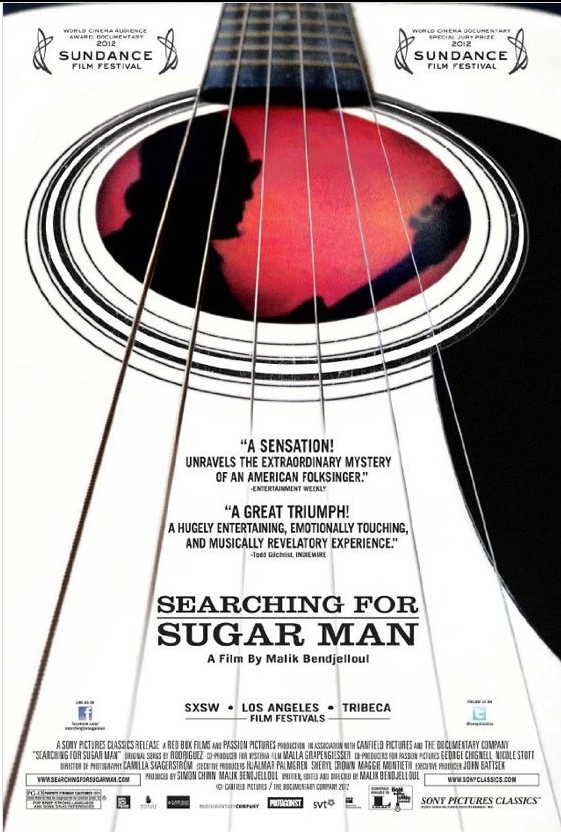

Searching for Sugar Man tells the true story of Sixto Rodriguez, an unassuming Detroit musician whose politically charged songs transformed him into a dissident hero in apartheid-era South Africa, even as fame and fortune eluded him back home. Swedish director Malik Bendjelloul’s feature-length debut spends its first half describing the mythology that arose in South Africa around this Mexican American singer-songwriter, and then delves — with surprising results — into the mystery of his sudden disappearance from the world stage.

Rodriguez was really big in South Africa. Just how big was he? “Much bigger than the Rolling Stones,” his South African distributor says matter-of-factly. Back home, one of his first U.S. producers hailed Rodriguez, the son of Mexican immigrant parents, as a “prophet.” His critically acclaimed songs invariably led to comparisons with Bob Dylan. So how was it that this outstanding artist bombed commercially in the States and was oblivious to his mega success overseas?

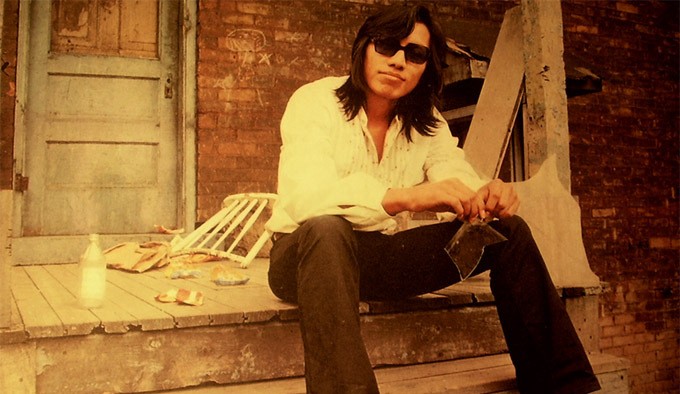

Bendjelloul starts the story in the late sixties, when Rodriguez was playing guitar in dusty Detroit clubs, keeping a characteristically low profile. The power of his voice and his songs eventually drew the attention of talent scouts. A local label, Sussex Records, invited him to sign a two-album contract.

Rodriguez’s first album, Cold Fact (1970), was praised by critics but never took off in America. Released in South Africa a year later, however, it struck a chord with young Afrikaners living under the country’s system of apartheid.

To maintain a radical segregation by race, the white-supremacist regime then in power brutally suppressed any form of dissent and heavily censored popular music and other media. (It would be another five years after Cold Fact was released that South Africans were introduced to television for the first time.) The apartheid state immediately saw Rodriguez’s music as a threat. Its censors physically scratched out the grooves of one of his tracks on the imported LPs of Cold Fact. The song? “This Is Not a Song, It’s an Outburst: Or, the Establishment Blues,” which halfway through makes its politics deadly plain: “This system’s gonna fall soon, to an angry young tune / And that’s a concrete cold fact.”

Rodriguez did not have apartheid in mind when he wrote those lyrics. Yet when the first copy of Cold Fact was somehow brought into South Africa, its songs quickly became anthems of the anti-apartheid movement, the smuggled albums and bootleg copies swapped among educated, middle-class young whites who identified with Rodriguez’s radical politics. At a time when Afrikaner indie rockers struggled to find their voice, Rodriguez’s lyrics directly inspired them and others of their generation to defy apartheid, long before such resistance was mainstream.

Beyond its politics, though, Rodriguez’s music was simply catchy — making it all the more dangerous to the apartheid regime. His popular song “I Wonder,” for example, is a clever fusion of breezy pop musings and the political concerns of an activist, all buoyed by an addictive bassline:

I wonder: how many times you had sex.

And I wonder: do you know who’ll be next?

(…)

I wonder: about the tears in children’s eyes.

And I wonder: about the soldier that dies.

I wonder: will this hatred ever end?

I wonder … and worry, my friend.

Amazingly, in spite of the censorship, Cold Fact went platinum in South Africa. By the eighties, it had become — for many white, middle-class South Africans, at least — an album as legendary as the Beatles’ Abbey Road and Pink Floyd’s Dark Side of the Moon. But Rodriguez was unaware of his fame in South Africa. For some reason, the royalties from his album sales there never reached him.

One of the film’s most riveting interviews is with Clarence Avant, the pioneering Motown producer and former head of Sussex Records, Rodriguez’s old label. On camera, Avant seems inexplicably skeptical of Rodriguez’s underground popularity in South Africa, and becomes defensive when asked about his missing royalties. Yet Avant never expresses any doubt about the musician’s exceptional talent. The producer who collaborated with Motown’s greatest places Rodriguez among the top five artists he has ever worked with.

But talent can have little bearing on fame, the film argues. A year after Cold Fact, Rodriguez came out with a second album, Coming from Reality. It, too, flopped stateside, and he was dropped from his label. Disappointed, Rodriguez disappeared from the scene. Among his fans, rumors abounded that he had committed a spectacular suicide on stage.

‘Nothing Beats Reality’

At this point, Bendjelloul’s film becomes a detective story of sorts: a cross-continental trek to piece together clues to Rodriguez’s current place of residence — or rest. For much of the journey the guide is South African record-shop owner Stephen “Sugar” Segerman, a passionate fan who took his nickname from one of Rodriguez’s signature songs, “Sugar Man,” about a drug dealer.

When Segerman was asked to write the liner notes for the 1996 South African re-release of Rodriguez’s iconic first album, he included an open invitation: “Any musicologist detectives out there?” Segerman called on his fellow fans to find out what exactly happened to Rodriguez. Music journalist Craig Bartholomew-Strydom took on the challenge.

The two South Africans started hunting for answers, but without any luck. Rodriguez had vanished. Fortunately, the nascent Internet provided some new tools for would-be sleuths. Segerman and Bartholomew-Strydom set up a website in 1997, asking people to contribute any information they might have about Rodriguez’s whereabouts. A year later, the pair was shocked to read a post from someone named Eva Rodriguez, who claimed to be the musician’s daughter. “Sometimes it’s better to keep the fantasy alive,” Eva wrote.

The film’s spoiler turns out to be a fantastic twist: Rodriguez was still very much alive, living in the same house in downtown Detroit that had been his home for decades.

When Bendjelloul finally puts the star of his documentary in front of a camera, Rodriguez comes across as stupefyingly grounded. Asked why he abandoned his short-lived music career to go back to earning a living through demolition and construction work, he shrugs. “Nothing beats reality,” says Rodriguez, who turned seventy in July.

Thanks to Eva’s own home-video footage of her father’s South African “resurrection” tour in 1998, the final part of the documentary grants us the emotional satisfaction of seeing Rodriguez standing serenely with his guitar before thousands of screaming fans at six sold-out concerts.

Here, and elsewhere, Bendjelloul allows Rodriguez’s music to carry the film. His soulful melodies set the atmosphere for sundry, occasionally animated scenes, while snatches of his sharp lyrics provide insight into the mind of a man of intense modesty.

Even if Searching for Sugar Man unravels the mystery of that man with more than a few loose threads, its passion for Rodriguez and his music is infectious. Not only directed, but also written, edited, and illustrated by Bendjelloul, this handcrafted, low-budget film shows every sign of being a labor of love.

It’s a Cinderella-like tale of talent and humility, perseverance and chance. And the story continues. The international release of this film, together with Rodriguez’s recent tour across the United States, heralds the third act of the artist’s life and musical career. Like Rodriguez, the story is very much alive.

Cherise Fong Cherise Fong is a bicycle traveler, writer, and journalist currently based in Japan.

- Follow us on Twitter: @inthefray

- Comment on stories or like us on Facebook

- Subscribe to our free email newsletter

- Send us your writing, photography, or artwork

- Republish our Creative Commons-licensed content