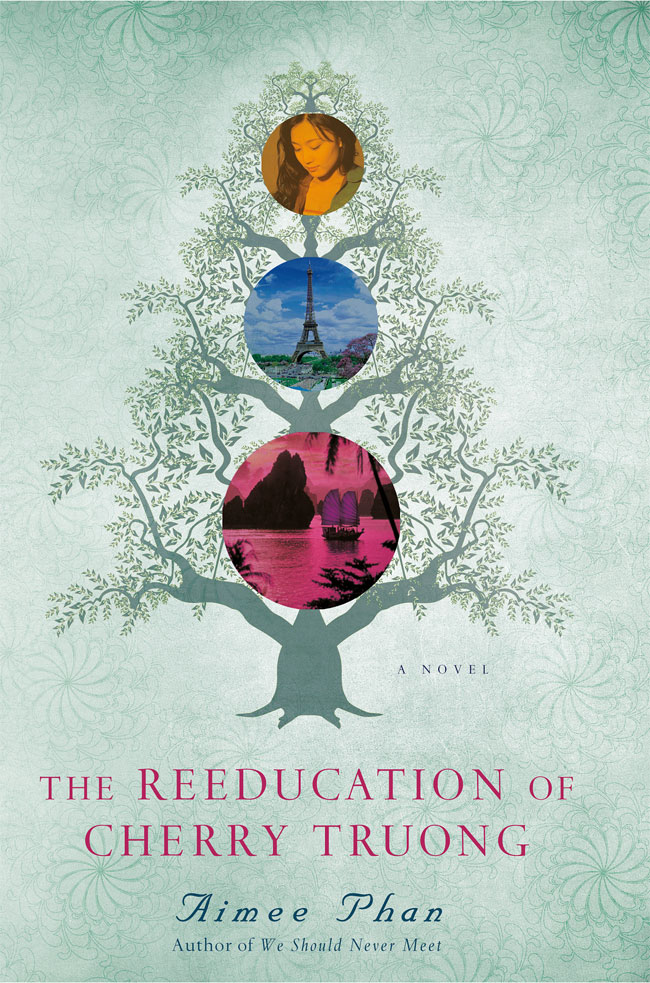

Spanning three decades across three continents, The Reeducation of Cherry Truong is a story of the fierce love, betrayal, anger, heartbreak, and forgiveness that can only exist between family members. Aimee Phan’s debut novel follows three generations of the Truongs and the Vos, two Vietnamese families tied by marriage. The novel illustrates how decisions made by one generation can cast a high, consequential shadow over the next generation, and explores the difficult balance between fulfilling our duty to family and keeping our sense of independence and identity.

Phan’s protagonist, Cherry Truong, is a second-generation Vietnamese American. After getting into a California medical school, Cherry disobeys her family’s wishes by deferring medical school for a prolonged visit to Vietnam to reconnect with her estranged brother, Lum. This is the first major act of rebellion in Cherry’s coming-of-age story.

Lum, who has a gambling addiction, was banished overseas by his family after he accidentally endangered Cherry’s life. Cherry goes to Vietnam to reunite with her brother, but she also has another purpose: Cherry is on a fact-finding mission to uncover her family’s past. Thus begins a narrative journey into the history of the Truongs, Cherry’s paternal side of the family, and the Vos, her mother’s side.

Set against a backdrop of historical events in the post-Vietnam War era, Phan’s story shows the pain of displacement. The year is 1979, four years after Saigon has fallen to North Vietnamese forces. The Truongs are attempting to escape Vietnam, aided by their middle son, Yen, who is waiting for them in France. Daringly, the Truongs set out to flee Vietnam by boat. But the Truong family patriarch, Hung (Cherry’s paternal grandfather), splits up the family. Hung had agreed to buy ship tickets to Malaysia, where the family could apply for political refugee status. However, he is unable to buy a seat for his daughter-in-law’s mother, Kim-Ly Vo (Cherry’s maternal grandmother). The family ends up in a refugee camp in Malaysia, while Kim-Ly stays in Vietnam.

In the refugee camp, the Truongs prepare for their journey to France, but the daughter-in-law, Tuyet (Cherry’s mother), convinces her husband, Sanh, that they should part ways with his family. This decision stems from guilt as well as love. Some years prior, Kim-Ly had tried to marry her daughter to an older and unappealing American officer. This marriage would have essentially guaranteed the Vos safety in America. Tuyet defied her mother’s scheme and ran off with Hung’s son, Sanh (Cherry’s father), instead. This was a blow to the Vo family, which suffered immensely during and after the war. Tuyet’s oldest brother died in a North Vietnamese forced-labor camp. After disappointing her mother yet again by leaving without her for Malaysia, Tuyet is desperate to rectify their relationship. She refuses to go to France by way of Manila, and seeks to immigrate to America, as her mother originally wished. Eventually, Tuyet and Sanh, along with the Vos, end up there, while the rest of the Truongs settle in France.

Later we discover that Hung had chosen not to get a ticket for Kim-Ly on the boat, as he had been holding out spaces for his mistress and illegitimate children. This one selfish decision alters the fate of the Truong and Vo families forever.

‘Our Mistakes Don’t Dictate Our Lives’

Phan deftly weaves her narrative back and forth through the past and present, and through three countries — France, America, and Vietnam. She describes how her characters grapple with displacement and assimilation, and explores their lives with an impressive level of emotional nuance. They have been shaped by both the tragedies they experience, Phan suggests, and their responses to these tragedies. At one point, Cherry remembers a fable about how “everyone has choices taken away from them,” and how “despair is pushed into our lives … [and] we can only control how we recover.” The experiences of Cherry’s family members parallel the fable. In the face of the great hardships experienced by the Truongs and the Vos, Phan shows us how the family members find different ways of coping — guilt, blame, anger, the displaced expectations of others.

In America, Phan introduces us to the world of Little Saigon, in southern California, where Cherry’s mother, Tuyet, is still atoning. She escaped the refugee camp, but it took her five years to get her mother out. In Little Saigon, Kim-Ly has invested in a successful beauty salon enterprise and has been loaning money to other Vietnamese families with interest. But she will not let Tuyet forget her transgressions.

While the Vos try to adjust to their new life in America, on the other side of the Atlantic the Truongs are pursued by their own past. In France, Yen’s wife, Trinh, suffers from a mental breakdown. Trinh is haunted by her experience in the refugee camp, but she will not seek help because she feels the need to protect her family from the truth.

Trinh is not the only Truong overcome by past traumas. Hung’s wife, Hoa, has been verbally and physically abused by her unfaithful husband. Hung insists that he has done his duty as a father by sticking with his family and not running off with his lover. However, his treatment of Hoa seems to reflect his frustration with losing his chance at happiness. Hoa endures her husband’s abuse and floats through her life without much complaint. When Trinh laments that a “family curse” befell them when they left Vietnam, Hoa replies, “Everyone suffers. We are not special.” When Hung later develops dementia in his old age, Hoa wonders if his illness “was not a tragedy, but rather nature’s way of correcting their relationship.” In one of Hung’s few lucid moments, she confronts him about his infidelities and tells him that his indiscretions will die with him. Hoa accepts misfortune but longs for catharsis.

Phan explores the family members’ relentless desire for reconciliation, and how this is often hampered by memories of the past. Many of the characters seem to remember too much; some, like Trinh, are almost imprisoned by their traumatic memories.

Cherry, who has a photographic memory, wants to make sense of why her family members keep hurting each other. She discovers old letters from her mother, Tuyet, to Kim-Ly, and catches a glimpse of the love letters from her grandfather, Hung, to his mistress. She uncovers some of her family’s secrets and finds proof of past indiscretions.

Yet, despite these revelations, Cherry realizes she is no closer to understanding why her family’s anguish runs so deep. She asks her brother if he thinks it might be better for their family to forget its past, to have “the worst memories erased.” Lum’s reply gets to the core of Phan’s novel. “The things our family did to each other, what we did to each other, they don’t make up who you are,” he says. “Our mistakes don’t dictate our lives.”

Susan M. Lee Susan M. Lee, previously In The Fray's culture editor, is a freelance researcher and writer based in Brooklyn. She also facilitates interviews for StoryCorps, a national oral history project. In her spare time, she maintains the blog Field Notes and Observations.

- Follow us on Twitter: @inthefray

- Comment on stories or like us on Facebook

- Subscribe to our free email newsletter

- Send us your writing, photography, or artwork

- Republish our Creative Commons-licensed content