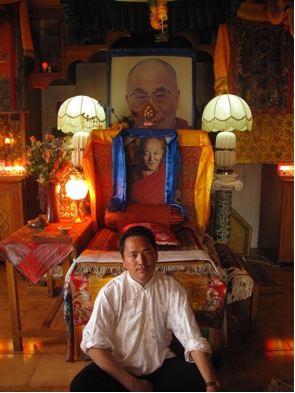

Waiting customers, mostly westerners who come to sip coffee at his cafe a minute, walk from the Tsuglag Khang, the Dalai Lama’s main temple opposite the god-king’s exile residence in the Indian Himalayas. Jamphel Sichoe comes from an immigrant background and knows what it is like to grow up with multiple traditions, having “chinky” little eyes which most ethnic Indians consider being of Chinese origin. Sichoe, 24, born in exile, works each day from noon till night attending to customers at his café. He wears an Indian dress, but in his mind are thoughts of his unseen homeland, Tibet.

Like all Tibetan shops, his cafe has a Dalai Lama portrait hanging on the wall, featuring a khata, a traditional scarf, as a holy gesture. During his long shifts, he stands managing the café, at times on with social networking sites on his MacBook. Though with each day’s hard work he finds himself restless – helping his Dad with English translations every morning, participating in various non-governmental organizations and Tibet support groups, organizing various human rights protests.

As the sun sets his old friends – Tenzin Chemi, Dolkar and Kalsang – come to meet at the café to sit around talking about their daily activity. Chemi and Kalsang were born inside Tibet but fled into exile with their family when they were 10 years old, following massive unrest inside Tibet. Both come from areas far inside Tibet, where technology and modern living are just dreams. Chemi and Kalsang are from Amdo province inside Tibet, while Dolkar and Sichoe are from Shigaste and Lhasa, in Tibet’s mainland. They all come from far corners of the large autonomous region now under Chinese rule. Chemi and his family crossed the border with the help of a guide and trekked through the mountains for more than a month before reaching Nepal, where he was kept in a Tibetan refugee center before being sent to the one in Dharamsala, the de-facto capital of Tibetans in exile in India.

They are the young guns of the exiled Tibetan community, educated to understand world politics and keeping up traditions, customs and religion in the midst of modernity. They talk about ethnic conflicts within the society; about disputes between the People’s Republic of China and their spiritual leader, the Dalai Lama; about the unrest they hear about inside Tibet and its outlying areas. About solutions to the political divide between generations in exile. About the Free Tibet movement. About lives and grass root problems they face each day, living in a land that is not their own with many complicated factors – poverty, racism, political or oppression. About the brutal suppression their countrymen have faced throughout their lives. Solutions to Tibet’s problems seem hard to come by, and hope is fast receding with the 74-year-old Dalai Lama aging; Tibet’s problems almost too numerous to count. They debate in Tibetan, Hindi and broken English, at times speaking typical local dialects, as if they were Indians making fun of each other.

As they finish meeting, Sichoe thinks of the day’s most important work he needs to perform – working with Tibet support groups until late in the night. He’ll be organizing tomorrow’s event, and a lot of effort has gone into this organization. The date is March 10, and this year it will be the 51st anniversary of the failed Tibetan Uprising against the Chinese rule, marking 51 years of the Dalai Lama’s flight into exile with thousands of his followers, who left their homeland in search of freedom and the desire to live their lives as they see fit. They say they did so to avoid political oppression and religious persecution.

Closing the café at 9, Sichoe walks back home down the steep road lined with deodar. The sky is dark over the Himalayas, and there is a shiver of cold despite the fact that spring is almost here. At home his eldest brother’s family waits for dinner. His father is a highly religious person and is early to bed after the evening prayers. Sichoe rests a few minutes before watching news on the TV, news of security beefed up in Tibet’s capital Lhasa ahead of tomorrow’s celebration of the 51st anniversary. Chinese police have cordoned off the entire city. His niece Choezom, who is half his age, listens carefully to the family’s conversation. She studies in a convent school where most of the students are local Indians.

Soon Sichoe finishes his dinner with his family members, and with many things to do for tomorrow, he meets his friends who await him down the street from his residence, and from there they all go straight to the community hall. There is a meeting with fellow refugees to discuss tomorrow’s event. Some of them prepare by writing anti-China, Free Tibet and human rights slogans on cardboard for display at the tomorrow’s ceremony and during protest marches on the streets. Sichoe helps other refugees, mostly newcomers, to get excited about tomorrow’s event. He stays up until midnight helping his friends, and then he goes back home, hoping for a successful event tomorrow.

**********

The light comes up above the animated settlement on its little ridge overlooking the Kangra Valley, and chants from the temple carry on the morning breeze. A gong sounds as the sun comes up above the snowcaps. The day has come that every Tibetan awaits: March 10. The morning before he goes out to attend the ceremony, Sichoe prays at his family’s prayer hall. Like many other Tibetans, he does the kora – the holy walk around the Dalai Lama’s residence and temple.

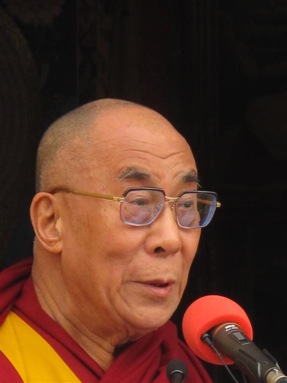

Thousands of Tibetan exiles and their supporters, most of them dressed in traditional silk and wool robes, gather in the compound of a Buddhist temple to hear the Dalai Lama and other senior leaders of the Tibetan government-in-exile on the eve of the day marking 51 years of exile. The crowds include hundreds of Tibetan children dressed in school uniforms, Tibetan nuns and monks in orange and maroon robes, and other young Tibetans with “Free Tibet” and Tibet’s national flag painted on their faces.

In the speech the Nobel Peace laureate blasted Chinese authorities, accusing them of trying to “annihilate Buddhism” in Tibet. His message has an impact in the refugee community that has made a visible effort to keep Tibetan culture alive – its language, crafts, and the practice of Tibetan Buddhism. Soon after the Dalai Lama’s speech thousands of Tibetan monks and youths march through the streets, shouting pro-Tibet slogans and praying for the Dalai Lama. The demonstrators, including those who followed the Dalai Lama when he fled Tibet and their children, all pledge support to their spiritual leader.

Indeed, new generations remain devoted to the cause. There have been no signs that Tibetans in exile here will give up their hope of returning to their homeland in freedom. And many are confident they will ultimately achieve their goal. An elderly Tibetan in the crowd says, “Don’t let anyone steal your dream. It’s our dream, not theirs. As long as there is no enemy within, enemies outside cannot hurt you.”

For the first generation immigrants, the image of the homeland remains quite vivid in the mind’s eye, despite planting firm roots in their new homes over successive generations. The images may gradually recede, but Tibetan people living in exile still hold firmly to the notion of freedom and rang btsan, or self-determination, hoping that their country will be given back to them some day. In fact, living in exile has only strengthened the resolve of Tibetans to regain their homeland.

Hundreds of Tibetans from different walks of life stage a massive protest rally, which starts from the main temple and culminates at a local bazaar. Huge presences of Tibetan protestors on the streets lead to traffic chaos. Since he has eagerly awaited this day, Sichoe joins the massive protest as well. Wearing the Tibetan flag over his back and marching down the steep roads from Mcleod Ganj down to the Indian bazaar in Dharamsala, he shouts slogans, appealing to world leaders to listen to their plight. The event climaxes in a candlelight vigil, with participants holding banners with slogans like “Stop torture in Tibet” and “China stole my land, my voice and my freedom.” Young radical groups shout anti-China slogans and call for rangzen, or full independence, for Tibet.

In the last 51 years, India has attracted many Tibetan refugees with its image of a slow pace of life and a peaceful lifestyle for refugees of all nationalities. This exiled community has created a new Tibet away from Tibet – a Tibet 2.0 — that aims to be more modern, more visible and more internationally connected than the real, existing Tibet over the border. There are over 12,000 exiles living in the valley; most reside in the suburb of Dharamsala known as Mcleod Ganj.

Sichoe’s father fled into exile in 1959 just after the Dalai Lama. Once in India, he lived with his family in Darjeeling and Mysore until 1981, and later in Madhya Pradesh in central India until 1990, quietly serving as a lama for the Tibetan community in exile throughout that time. Sichoe was born in Chattisgarh, an Indian state, but soon his family moved to Dharamsala to be closer to His Holiness, the Dalai Lama. He went to school at the Tibetan children’s village where all Tibetans get educated, mostly funded by support organizations. Sichoe believes he’s living in the world’s most successful refugee community, but this wasn’t his peoples’ aim. Many refugees feel they have no purpose and meaning in life. The pain of being an exile is that you do not belong where you stay, and you cannot return where you belong.

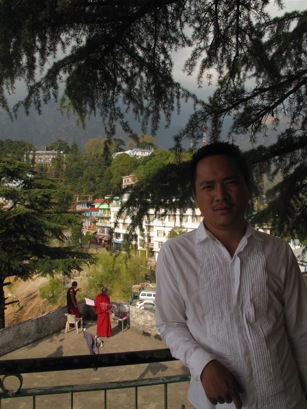

For Sichoe life in Dharamsala is a positive, multicultural, and diverse experience of everything from “shanty” to Bollywood, which he enjoys. Still, though, there is sadness. Sometimes he forgets he’s a refugee, but at the end of day he remembers. He believes that China thinks every Tibetan in exile is a criminal, and he wonders if he is.

The night after the candlelight vigil, Sichoe, drained of energy, returns home. The buzzing town is full of travelers and Tibetan shops remains closed all day to commemorate the event. At home his family prepares the special dinner when all members of the family will sit together, eating, before the short prayer. Tibetan dishes fill the evening after the day’s hard work, with soup bowls, mutton momos, tingmo, the Tibetan bread, rice noodles, chicken and thupka all served at the table in a small room and presented with Tibetan Thangkas.

After the special dinner, Sichoe helps his family clean the room while others collect the plates to wash. His niece Choezom enjoys time with Sichoe, sharing with him her day’s activities. Tired, Sichoe wishes all a good night and walks to the front of his room. As he enters his room he sees one of the cardboards he prepared the night before, on which he wrote “China: respect human rights in Tibet.”

*******

Sichoe wishes to return to his homeland as a Tibetan, not a Chinese. India is the best country for refugees, but it’s not the same as being a citizen of his homeland. Sichoe’s homeland Tibet is a plateau region in Asia. Often referred as “Roof of the World,” Tibet is the highest region on earth. During Tibet’s history, it has existed as a region of separate sovereign areas, a single independent entity that is now under Chinese sovereignty. Approximately 6 million people live across the Tibetan Plateau, and about 150,000 live in exile, who have fled from modern-day Tibet to India, Nepal, and other countries.

However, for Tibetan refugees, the picture is quite different. They left their homeland in search of freedom and escape from the Chinese dominance over the region. With 51 years in exile, most refugees and their children have been forced to resettle throughout the world. The Dalai Lama’s seeds of compassion are helping young refugees to settle and maintain their ethnic culture.

Tibet is extremely hard to reach, but China’s recent development has connected it to the world, despite it being hemmed in on the south by the Himalayas and on the north by the almost equally high Kunlun Mountains. The terrain is inhospitable, since the plateau itself is about 15,000 feet above sea level. The climate is harsh, with violent swings of temperature between night and day at all times of the year. It is well-known as the “Third Pole of the Globe.” The world’s highest summit-Himalayan, which strides across the boarder between China and Nepal, claims a height of 8,848 meters above sea level. Lhasa is the administrative capital of the Tibet Autonomous Region in the People’s Republic of China. It is located at the foot of Mount Gephel. The city is the seat of the Dalai Lama, the location of the Potala and Norbulingka palaces having names in World Heritage Sites, and the birthplace of Tibetan Buddhism. The Jokhang in Lhasa is regarded as the holiest center in Tibet.

All young Tibetan exiles are torn between these two views of Tibet – one magnificent, the other horrible. For Sichoe his homeland is far from sight. He was born in Chhattisgarh, a state in India. His father is the 9th Jestun Dhampa, the most religious figure in Mongolia after the Dalai Lama. Khalkha Jetsun Dampa is considered one of the most revered teachers of the Kalachakra Tantra, the Tara Tantra, and Maitreya, the future Buddha. His incarnation was recognized, at the age of four, by Reting Rinpoche, the Regent in Lhasa, as well as other high lamas and the state oracles. His identity was kept secret due to Stalin’s influence and oppression in Mongolia. At the age of 25, he gave back his monastic vows, and then went to stay at Ganden Phunstok Ling, established by his predecesor Taranatha, until the age of 29 when the Chinese invasion forced him into exile, along with hundreds of thousands of Tibetans.

Then, in 1991, with the dissolution of the Soviet Union and the newfound religious freedom in Mongolia, many Mongolian monasteries sent their abbots, lamas, and ministers to India to discuss with the Dalai Lama, in Dharamsala, the possible location of the Ninth Khalkha Jetsun Dampa. It was at that time, through the Religious Office of the Tibetan Government in Exile, that the Dalai Lama gave the official stamp of recognition and acknowledgement of the Ninth Khalkha Jetsun Dhampa, the spiritual head of Buddhism in Mongolia.

Sichoe is grateful for the teachings he’s gotten from his father. For him he feels 60 percent Tibetan, 20 percent Indian, and 20 percent American. His country will be wherever he’s make his living.

Thousands of mainly young Tibetans have escaped to the small hill town of Dharamsala, which has turned people from poor, rural Tibetan areas with little education, business and few career prospects in China into professionals whose horizons extend around the world.

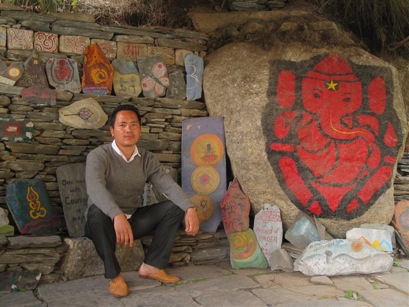

As home to the Dalai Lama, the Karamapa Lama, Tibet’s third highest spiritual figure, and other high-ranking lamas and monks, Dharamsala is the heart of Tibetan exile life, and its hills are adorned with Tibetan prayer flags. The town, where monks and nuns outnumber tourists, is also thronged with small cafes, bustling with activity as monks perform their daily routines and teach courses in Buddhism, while locals engage in community activities such as volunteering as teachers. The Tibetan equanimity is striking. The town is smaller than an average county town in China and possesses modest economic resources, yet there is a notable calm. Some of this may derive from the regular stream of new arrivals from Tibet. They have not risked their lives on tough journeys across the Himalayas to begin the next phase of their lives as refugees. Some want a better education, some want to become monks in monasteries, some just want a better life.

Recent Tibetan refugees even speak Chinese. A favorite pastime of the younger ones is spending time in Internet cafés, watching Chinese video-clips and chatting online. Tibetans making international calls to their relatives and friends on the other side of Himalayas often talk in Chinese. The young refugees are growing up defying easy definitions; the children of exile are slowly coming of age.

Sichoe knows time is running out, and even if he doesn’t go back, he’s ready to work and help his exile community. “I will work in the Tibetan government, may it be in exile or back inside Tibet, bringing more and more reforms is the need of the people,” Sichoe says. With a Bachelor of Arts degree from Delhi University, he’s talented, modern and has a Tibetan blood for struggle. He shares his thoughts about the life after the Dalai Lama, when Tibetans will have to struggle even more than they do today, but he’s ready as life moves on.

“Here, it’s like a confused cocktail of my citizenship – half Tibetan, half Indian and now with western culture rooting in us, it’s a blend,” he says. To go back to his homeland is his dream, like it is for many refugees. As each day dawns, Sichoe will walk the kora, and later he’ll help his father with English translations, then go back to the café at noon. For now, he sits on a stone overlooking the high mountains, dreaming of Lhasa.

- Follow us on Twitter: @inthefray

- Comment on stories or like us on Facebook

- Subscribe to our free email newsletter

- Send us your writing, photography, or artwork

- Republish our Creative Commons-licensed content