In the fall of 2002, I was teaching third grade at an independent, coeducational elementary and middle school in Manhattan. As October rolled by, I asked a student what he was going to be for Halloween.

“I’m going as an Indian,” he said, excitedly. He seemed to be looking forward to the upcoming candy fest. But to me, his response was a flag — a big red flag with “teachable moment” written all over it.

Zoom ahead several years to a graduate-level class about “otherness” at the New School for Social Research in New York. One Monday evening, our discussion turned to multiculturalism, terminology, and political correctness in schools. The question on the horseshoe-shaped table was does the term “multicultural” actually impede our ability to connect with “the other” in our lives?

As a teacher-turned-graduate student, I listened intently to my classmates sound off on the hot button issues: Multiculturalism is inappropriately associated with racial diversity, given the fact that the two are very different concepts. “Diversity Day” and “Multicultural Month” too neatly divide from the rest of a classroom’s curriculum the fact of diversity. Schools should abolish programs devoted to multicultural awareness and instead, simply be diverse institutions. Terms used in schools should reflect the latest in social thought, otherwise how can we raise kids who will become conscious and sensitive adults?

When I became a schoolteacher in 2001, multiculturalism and diversity curricula were considered good things. Multicultural activities and books were part of the curriculum. Diversity coordinators were being hired in many of the private schools, and teachers were applying to attend national conferences on diversity. The National Association of Independent Schools (NAIS) offered Diversity Leadership Awards each year.

But now, in graduate school, I listened to my classmates (much younger than me, just out of college, and with no teaching experience) and wondered about their thoughts. I didn’t necessarily disagree with them. My classmates, however, were demonstrating a typical problem. In graduate school classrooms, think tanks, non-profit organizations, and government offices, issues like diversity in schools are debated all the time. New terminology replaces the old, things become politically correct or incorrect, theorists publish controversial articles, minority group representatives speak about rights on the evening news, and social movements sweep along. We adults absorb the latest in what we should and should not to say.

Teachers try to stay updated. But could I have kept my eight-year-old students aware of the changing thought about, say, the issue of how to refer to American Indians? Aware enough so that in that one moment in time — the Halloween costume remark — we all would spew the most fashionable term?

A glimpse into the classroom

Though private and public efforts to jazz up schools do make a difference in keeping classrooms and curricula up-to-date, many classrooms — and I’ll speak only of my experience in two Manhattan private schools here — are a little bit like museums of childhood. Mine certainly were. It starts with the stuff you can still find in classrooms. A tinkerer like me might like to grind the old pencil sharpener, with lead marks dating back 40 years. (We had an electric sharpener, too, but it broke far more often than the grinder type did). A book collector could pore over yellowed copies of Mrs. Piggle-Wiggle and Winnie-the-Pooh. Who can deny the charm of framed children’s drawings whose creators are now middle-aged?

Then again, picture the classroom as a landfill. Many classrooms are stuffed with musty piles of papers. Chipped paint reveals layers of unfashionable color choices, as if you could peel back each one and reveal the philosophy of the day on the walls. If you hunt, you can still find a slide rule or a U.S.S.R. picture book. Some classrooms are just not cutting edge, regardless of what the admissions brochures say. Ideas and the materials used to teach them, for better or worse, tend to endure through generations.

The age of things extends to ideas, of course. Lesson plans that worked are recopied, while lesson plans that didn’t are filed into three-ring binders and kept for reference. If there’s a binder for “Diversity Day,” it gets recycled year after year. My classroom was chock-full of evidence of the greatest ongoing education experiment: trial and error. Like a museum (or a garbage dump), a classroom encapsulates nuggets of human thought.

It’s not that the curriculum is totally immune to the changes “out there.” In fact, like vaults run by pack rats, classrooms serve as the perfect repository for the ideological debris of political campaigns and social movements. What starts as dialogue or dissent in think tanks and graduate classrooms is inevitably dumped into teachers’ laps along with the immediate events of the day. Teachers must marry the politically correct, culturally sensitive world with the violent, offensive world, and translate the result into a civically and environmentally responsible yet age-appropriate curriculum.

Consider the teacher’s task after hurricane Katrina, or during last fall’s election, when Martin Luther King’s image could be viewed regularly on the news and the name Lincoln was dropped into more conversations than I can recall in recent history. Consider the teacher’s task on September 11, 2001. That, in fact, was my fourth day of teaching: streams of soot-covered office workers filing past the school, panicked parents trying to push their way upstairs to collect their kids and take them home, the head of my division explaining to students that “bad things happened to America today, but you are all safe.”

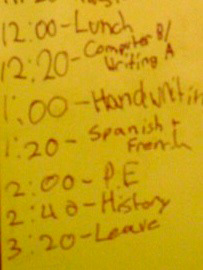

Again and again, new worksheets are created, new lesson plans put into place, new safety plans written, new “current events” times carved into the school day.

The questions at hand

So when my student said, “I’m going as an Indian,” what should I have done? My graduate classmates might have offered multiple choices: Remind him that a recent trend is to use the term “Native American”; explain that an even more recent trend is a backlash against the label “Native American,” against labeling at all; tell the boy he ought to use the officially recognized term “American Indian,” but compliment him for getting it close; use the moment to explain that dressing up for Halloween as an ethnic or racial identity instead of as a mouse or a pumpkin could be considered offensive, because reducing said identity to costume pieces perpetuates negative stereotypes. I did work through several options in that moment in 2002, but by the time I was ready with a response, the boy was long gone, off to the book nook where, I can imagine now, he pulled The Indian in the Cupboard from the shelf.

But I was new to teaching then. I have quicker reflexes now.

What am I getting at? Something I wish I had gotten at with my graduate classmates. That teaching is already a difficult job. Keeping eight-year-olds up-to-date on the political and social changes in our world, contextualizing those changes for them from the previous status quo, as politically incorrect as it may have been, and creating anew each day a curriculum that matches the latest in current events? We do our best.

I sat down with two teaching buddies who still work with the elementary school set and asked them about politically correct terminology. I’ll call them Scott and Amanda. Both work in private schools in Manhattan, both have graduate degrees in the field of education, and both were eager to discuss how, as teachers, they handle changing thought on race, ethnicity, class, gender, and sexuality.

“Would it faze you if a child said, ‘I’m going to be an Indian for Halloween’?”

“Deep inside, I’m feeling, uh-oh. This could end up being very stereotypical,” said Scott. “It raises questions of what representations on Halloween are inappropriate.”

Scott’s school allows costumes on Halloween, though within reason. Students are sometimes pulled aside and asked to alter details of their dress — I remember the debate over a fake cigar, complete with burning end, one year. Amanda’s school has a no-costume policy, though parents provide candy parties in the decorated classrooms.

“I think I would ask the student about his costume,” said Amanda. “Like, what are the things we learned about Native Americans that you incorporated into your costume?”

“So a gentle change of term?” I asked.

“I actually use the terms ‘Native American’ and ‘Indian’ interchangeably,” said Scott. “I think it’s important to understand the history of the words.”

In the moment the student told me he was “going as an Indian,” I didn’t know the history of the words, nor was I up-to-date on the latest best term choice. So I did what I always tell my students to do: I researched.

A brief history of names

It appears that when Christopher Columbus hit land and was hit with the urge to do what all explorers do — name things — he might have had one of two thoughts. Either he rejoiced, “We made it to the East Indies, or India, or somewhere over yonder! Check out the Indians!” (Sarcasm mine.) Or, improbably, he mused, “These spiritual people are with God, with Dios.” That seems like a long shot to me, and I could not find any sources to back it up save for some hobby historians writing about it on the Internet.

Either way, or for some other reason that never seems to have made it into our history books, the label “Indios,” and then “Indian,” was attached to Seminole, Pequot, and Sioux alike. “Indian” became the catchall word for anyone explorers and settlers met along their journey. It gained recognition worldwide, and some languages even adopted new words to differentiate between Indians of the Americas and Indians of India.

Then came the 1960s. Indians, along with non-Indian supporters, voiced objections to the term they’d been labeled with for centuries. Aside from the fact that it could have been a colossal geographical mistake by Columbus, the term “Indian” had become a bit of a joke. The dawn of film and cheap plastic toys had given Indians a bad name. Cowboys and Indians were so strongly made representative of good and evil, civilization and savagery, respectively, that many people believed the only way to erase the stereotype was to erase the name.

Thus Indians were reborn again, this time as “Native Americans.” “Native” because their ancestors were here before anyone else, and “American” for obvious reasons. Sensitive anthropologists informed the government of this new label, and the government promptly absorbed it into its classification system.

The term “Native American,” however, provoked some questions of logic. What makes a person native? Birth? If so, there’s a whole bunch of us in a big happy native, if not Native American, family. And “American,” like “Indian” before it, supplanted the beloved tribal names that existed long before Vespucci did.

By the 1980s, many acknowledged they preferred the old way. But the term “Native American” has nonetheless stuck around, to the dismay of some. Comic George Carlin bites at the “pussified, trendy bullshit phrase.” Cherokee writer Christina Berry requests that “Indian” be used but with contextual sensitivity (avoid the worst: “Injun” and “redskin”). Lakota activist Russell Means wants his people to call themselves “any damn thing we choose” and refuses to be classified as “Native American.”

In addition to “Native American,” the vast machinery of label production has spit out “Original Americans,” “Indigenous Americans,” “Amerindians,” “First Americans,” “First Nations,” and “Aboriginal Peoples,” to name but a few. The vast machinery of academic and activist opposition has spit back a reproach for each one, though you can’t completely fault those who try out “Native American Indian” or “Aboriginal American Natives” in a misguided attempt to get it right at both ends.

The U.S. government officially uses the term “American Indian,” while the Canadian government has adopted the term “First Nations” in place of “Indian” and lists the name under the umbrella term “Aboriginals.” The term “Indigenous Peoples” encompasses a wide range of tribes in Mexico and Central and South America.

When I sort through the often contradictory materials, the phrase that comes to my mind is political scientist Walter Connor’s “terminological chaos.” And this chaos is faithfully documented by the caretakers of education, in the filing cabinets and on the bookshelves of American classrooms.

Meanwhile, back in the classroom

Both Scott and Amanda teach social studies curricula that rely heavily on the heritage of the American Indians. November is both National American Indian Month and Alaska Native Heritage Month, and much of the commemorative excitement plays out in their classrooms. Scott’s school invites the Red Hawk Council Dancers every year, who, if I remember correctly, explain to students that what they have seen of American Indians in the movies isn’t always true. Scott also takes his students to the Museum of the American Indian. They don’t know the museum is one among many getting heat for not returning Indian artifacts to the tribes who claim them.

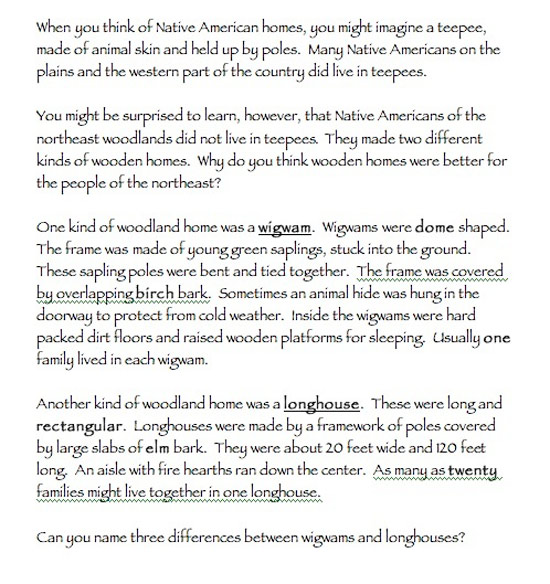

A bulletin board announces “Native Americans!” in bright red punch-out letters and is tacked full of “indigenous artwork.” I remember devoting a stretch of wall to the “False Face Society,” lined with Iroquois-inspired masks made of paper and markers, only to learn that I may have been making a major cultural intrusion by allowing my students to create their own false faces. For a long time, I reminded my students to walk “Indian file” (one behind the other) and sit “Indian style” (knees bent, legs cross), because I had grown up with these terms. I grew out of them, however, and started to say simply “single-file” and “cross-legged.”

Amanda reads The Indian in the Cupboard to her students.

“Do you adjust the term as you read?” I asked.

“No. The books are dated and are still in the classrooms,” said Amanda. “People don’t get brand new materials with the latest political material in them. They’re not interested in the idea that there’s a controversy over a name.”

Amanda said that even in middle school history classrooms, where her husband teaches, “Half the books say one thing, half the books say the other.”

There are a few resources a teacher might use to make sense of the terminological changes for his or her students. In 2002, a book called Contentious Issues by Márianna Csóti appeared in the United States. It’s a book about big ideas for little kids, as the title suggests. One section of this stereotype-destruction manual reads like a laundry list of terms you can use to get beat up at a bar: “Paddy, Paki, Sambo, Spade, Spick/spic, Spook, Taffy, Wog, Wop.” What comes between “Paki” and “Sambo” is “Red Indian,” an archaic British phrase that is still used by some to distinguish between American Indians and Indians from India. Many condemn the term as disparaging on the basis of race, and others wonder why black and white remained okay whereas red and yellow fell into disrepute. Csóti encourages adults to be clear with children about terms. “Red Indian” is racist, “Indian” is politically incorrect, “Native American” is “not wholly acceptable,” and the child’s best bet is to go with “Indigenous.”

I can only imagine what reaction the book would receive in my graduate school classrooms. Outrageously offensive? Possibly harmful, feeding the fire by putting words in kids’ mouths? Perpetuating a classroom environment in which difference is too starkly highlighted? Politically incorrect?

To me, it’s a saving grace kind of book, something to help put all the rapidly changing thought into one place. I asked my teaching friends about it.

“I have an increasing apathy toward political correctness,” Scott told me. “There’s always something new. I want to understand and be compassionate and considerate, but in the end, it’s about the values you project as a teacher.”

Scott was faced with a teachable moment himself when reading Runaway to Freedom by Barbara Smucker with his students.

“The book used ‘nigger’ quite often,” Scott said.

Runaway to Freedom is a historical fiction novel geared toward kids in the nine-to-12 years category, and it reveals, in context, how the word “nigger” was used in the 19th century.

Scott continued. “I asked my students, ‘Do you all feel comfortable going on with this? We have until tomorrow to decide if we’re all comfortable. Go home and talk about it. If anyone has any concerns, let me know.’ I checked in with the administrator, too.”

In the end, Scott’s administrator approved, and his students decided it was okay, that they would learn about the word in context.

“I was actually really moved by the book, but it was hard to read,” said Scott. “We agreed we wouldn’t actually say the word, we would just say ‘N.’ The kids took it very seriously.”

“It’s about teachers with good intentions who want to do the right thing,” said Amanda. “You can’t shield students from the idea that bad words exist, or that there are really ugly moments in American history.”

“In the end, the lessons you’re teaching — about different cultures and the history of a place — are about understanding the humanness of things,” she added. “They’re about building understanding for otherness.”

- Follow us on Twitter: @inthefray

- Comment on stories or like us on Facebook

- Subscribe to our free email newsletter

- Send us your writing, photography, or artwork

- Republish our Creative Commons-licensed content