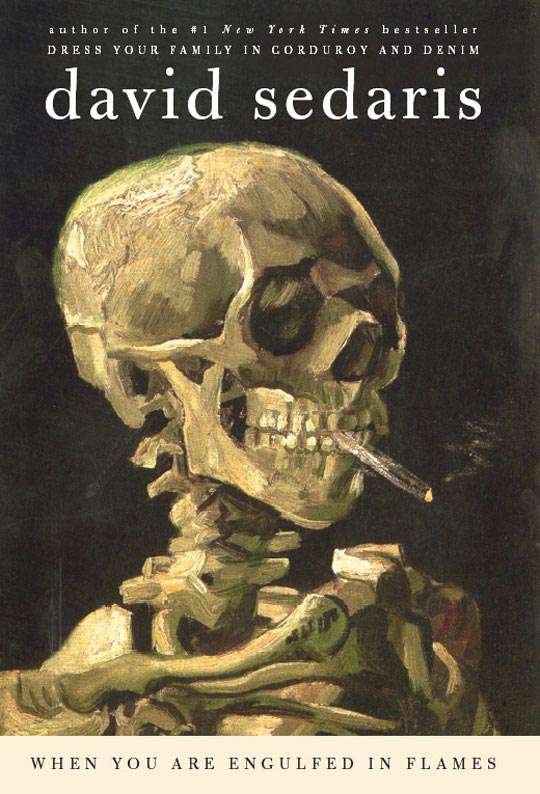

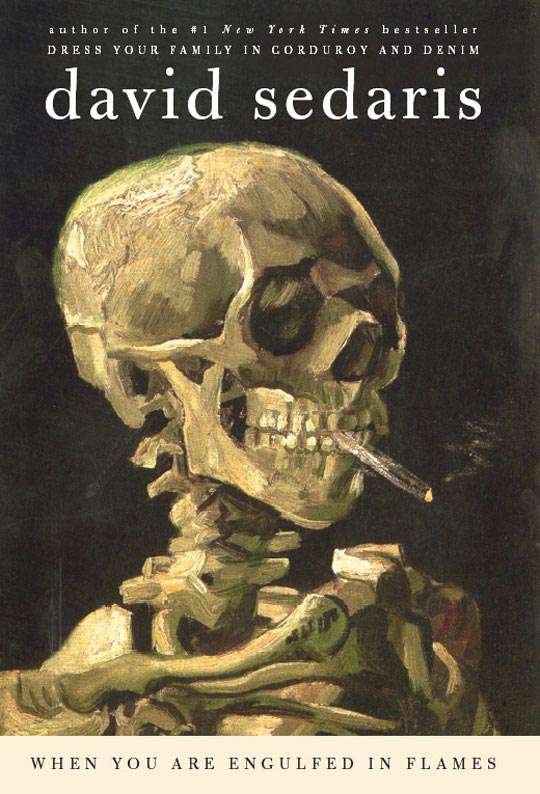

After selling millions of books worldwide, penning an Obie Award–winning play with his equally well-noted younger sister Amy, and cultivating the kind of sweater-vested, lefty politico audience that must keep the suits at National Pubic Radio (NPR) waist-deep in spicy tuna rolls, how exactly does David Sedaris manage to keep himself fresh and culturally relevant? At the top of his game, Sedaris has always been the thinking man’s humorist — the kind of literary lothario that even your grandmother has heard of (and adores, naturally). Now, with his sixth collection of witty, observational-styled essays, When You Are Engulfed in Flames, Sedaris has reached a crossroads in his epic career: either grow with your core base, or fade into pop cultural obscurity.

When You Are Engulfed in Flames, along with its accompanying global book tour, can best be viewed as an ongoing case study in misfit dysfunction — a natural continuation to Sedaris’ trademark genre of wry, autobiographical narration. Whereas his previous collections have revolved primarily around the outrageous hijinks of his thoroughly unpredictable Greek family, the stories presented in Flames display a heightened sense of maturity and confident self-awareness, the sort of which that courses breathlessly through every page and every chapter. If Me Talk Pretty One Day, Sedaris’ 2000 release about moving to France with his partner and his struggle to cope with learning a foreign language while thriving in a foreign land, stood as his literary adolescent years, then Flames represents full-fledged adulthood: a coming-out party for a now-seasoned world traveler; an awkward pupil of culture now especially skilled at the unusual art of adaptation.

As its inflammatory title suggests, Flames spends more than 300 pages highlighting emotions of fear and discomfort and the many perils of frequent travel, and no one recreates the outsider experience quite as vividly as Sedaris (in classic, peak form) does. There’s a reason why he is able to affix the title “noted humorist” to his business cards, and in Flames, the humor is no less sharp or wryly observant than in prior works. The difference here is that Sedaris is writing from an interloper’s perspective more frequently than he has in the past, and his descriptions of third party discomfort play as well as the book’s more personal elements do.

An early chapter entitled “Keeping Up” finds Sedaris watching vacationing American couples arguing loudly outside of his apartment window, taking desperate stabs at figuring their way around Sedaris’ adopted home of Paris, while concurrently mangling the French language as though it were a garbage-bound piece of paper. (One woman even mistakenly believes that her meager Spanish skills will suffice for the trip.) Still another story brings Sedaris to the doorstep of his father’s neighbors in Raleigh, North Carolina, where he makes acquaintances with a flamboyant 15-year-old, whose own Southern-fried parents proudly proclaim to be a homosexual. Odd, Sedaris sniffs in his biting narrative. In his own Southern childhood, identifying oneself as gay would have been nothing short of a death sentence; you’d have to find yourself a girlfriend “who was willing to settle for the sensitive type.”

The best story in Flames, however, is the memoir’s last: a multipart epic about the author’s two-decade-long love affair with smoking cigarettes and subsequent decision to give them up for good. It’s an arduous undertaking that has Sedaris and his partner, Hugh, relocating to Japan for a three-month excursion, steeped in the fundamental principles of cultural misfit-hood. Broken up into three distinct sections — “Before,” “Japan,” and “After,” respectively — the story offers an inside man’s perspective into Sedaris at his very best and most introspective, and indeed, the entire account reads as though the passages were copied directly from the pages of his diary. “The Smoking Section” is equal parts poignant and melodramatic, altruistic and self-serving, all at once. It is here that Sedaris demonstrates his remarkable ability to spin seemingly mundane scenes into funny and interesting lifestyle pieces, with no shortage of heart. By its conclusion, one can’t help but wonder why moving to Tokyo wouldn’t be just as, if not more, effective a method for kicking butts as attaching an endless parade of nicotine patches to one’s forearm would be.

As a performer, Sedaris’ star shines equally as bright, but in a radically different manner than his comedic persona radiates when regulated to the page. Currently underway on a multicity North American book reading tour, Sedaris has taken to reading out loud from works by other authors, a few of his as-yet unpublished essays, and even a smattering of excerpts from his personal journal, offering a rare glimpse of the author when he is unfiltered by the bounds of the editing process.

It’s fun to watch Sedaris relay his unique brand of offbeat, awkward humor to the audience in person, and listening to the introductory origins of each story provides the kind of elated enhancement that is more often applied to the most cherished of fantasy fiction, but rarely to the kind of observational memoir writing of which Sedaris has repeatedly proven himself a master. Robbed of the protection of editors and literary distance, many equally capable writers would more than likely find themselves foundering onstage. In his public readings though, Sedaris demonstrates that, on paper or off, he’s able to use his biting and keen sense of humor to make pathways into his audience’s hearts; put quite simply, he’s just a funny guy.

Converting humor from the page to the stage is no easy feat, and many fine nuances are often sacrificed in translation. The fact that Sedaris has been able to consistently maintain a long-lasting relationship with his avid readers stands as an overwhelming testament to his genius and talent as both a writer and a performer. The trick to remaining relevant is to grow and mature with one’s audience — a difficulty that has seen many gifted artists forfeited in its wake. Sedaris, conversely, continues to regenerate the kind of radiant humor and spark in both his writing and his performing that has simultaneously drawn in younger readers while keeping his core base unwaveringly interested. Upon reaching the summit of Flames, one gets the sense that this isn’t Sedaris’ zenith; rather, it’s something of a new beginning.

- Follow us on Twitter: @inthefray

- Comment on stories or like us on Facebook

- Subscribe to our free email newsletter

- Send us your writing, photography, or artwork

- Republish our Creative Commons-licensed content