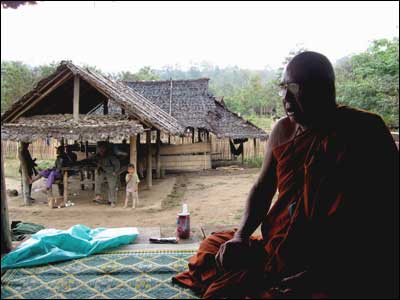

In a jungle encampment in eastern Myanmar, 67-year-old monk Saw Wizana sits meditating in orange robes. Behind him, hundreds of men with semi-automatic weapons line up in military formation and march in circles around a field. They are preparing for another battle against Myanmar’s military government.

Saw Wizana and the soldiers are Karen, the largest ethnic group in Burma. They have been fighting the government for 60 years in what has become the world’s longest running civil war. While tens of thousands of monks caught the world’s attention last August and September for their massive nonviolent protest, some Buddhist clergy in Burma — including Saw Wizana — insist that violent resistance is the only viable strategy against the ruling junta. Today, monks from both schools of thought continue to battle the military dictatorship. They say they belong to the same revolution.

Saw Wizana argues that as a Buddhist monk, he supports the controversial Karen armed struggle because he says it saves lives.

“We want to use a peaceful way like Martin Luther King, like Gandhi, but the military regime doesn’t accept it. That’s why we have to pick up arms,” he said. “Of course we want peace. Everyone wants peace. But it doesn’t work. That’s why we need weapons. We only use them to defend ourselves.”

The Saffron Revolution, brutally suppressed

The Buddhist country of Myanmar, named Burma until 1989, is among the most oppressive in the world. Pro-democracy advocates are routinely imprisoned, and ethnic groups like the Karen are regularly attacked by the military government.

Until recently, because of the government’s stranglehold on dissent, only the Karen rebels have openly confronted the dictatorship. But in August and September of last year, when tens of thousands of monks became involved in what originated as pro-democracy and student protests against rising fuel prices, a nonviolent resistance was reborn.

After days of nationwide protest dubbed the “Saffron Revolution,” the monks were brutally beaten and shot at by the military.

Monk Saw Wizana says the tragic result of September’s protests, in which at least 31 people were killed and hundreds imprisoned, proves that nonviolent resistance won’t work against the Burmese dictatorship.

“Nearby countries like Sri Lanka, Laos, Cambodia, and Thailand — they are all Buddhist countries, and they wouldn’t hurt monks,” he said. By contrast, in Myanmar, he added, “monks were tortured by the military soldiers and forced to worship their torturers.”

Buddhism and armed struggle

Saw Wizana — an imposing, heavyset man with gold wire frame glasses and rolls of orange fabric — has been a monk for 37 years. He spent four years in prison between 1984 and 1988, and was forced into hard labor as punishment for challenging the government.

“I was in the forest with several young students I was teaching. When we were sleeping, the military shot my students because we are Karen,” he said. “I told them they were breaking the law, and because I talked back to them, I was put in prison.”

He insists the Karen armed struggle is not in conflict with Buddhism because it is protecting life.

“We have to use it together with religion,” he said. “Use weapons for defense and religion to keep us courageous.”

Of the armed groups that have fought Myanmar’s dictatorship, all but the Karen have surrendered. The Karen National Union (KNU) comprises Christian, Buddhist, and Animist ethnic Karen people, and has suffered major troop losses over the decades. The KNU estimates its forces are outnumbered by government forces at least 25 to 1.

The KNU is also criticized for planting landmines, recruiting child soldiers, and instigating violence in civilian areas — accusations they deny.

At KNU headquarters, Saw Wizana is known as “Monk Rambo.” Other monks say they too understand the Karen armed struggle. One of them, 53-year-old Oh Bah Seh, was a leader of last year’s protests and says he does not condemn the Karen war. He is neither Karen nor part of the KNU movement. “No one wants violence, but because of the inhumane persecution [by] the government, that is why some came to take arms to fight the evil system.”

He, however, practices nonviolent resistance, like most other Buddhist monks. He says that as he was being beaten with a stick during the September protests, he still continued chanting loving kindness toward his oppressors.

Nonviolence is key, others say

Twenty-eight-year old Ghaw Si Tha, another leader of September’s peaceful marches, said nonviolence is key to a Buddhist resistance.

“We must go on chanting love, as we are monks. Even though they use force, even though the regime doesn’t follow the Buddhist precepts, we have to be faithful to love,” he said. “We believe that only love can produce success. That’s why we march with loving kindness, peacefully without violence.”

In Myanmar, political resistance by Buddhist monks dates back to British colonial times when Buddhist clergy helped fight for independence. The Buddhist clergy are a venerated group, seen by the general public as leaders. Today, Myanmar’s 400,000 monks are a group outnumbered only by the military.

Although unwilling to give specific details, monks Ghaw Si Tha and Oh Bah Seh say there are plans for future nonviolent protests in Burma. Many suspect August 8 — the 20-year anniversary of the massive pro-democracy protests, as well as the opening of the Beijing Olympics — to be a day to watch in Myanmar.

“Now, in this way, we Buddhist monks are also doing the same thing as the Karen fighters,” said Oh Bah Seh. “Revolution.”

- Follow us on Twitter: @inthefray

- Comment on stories or like us on Facebook

- Subscribe to our free email newsletter

- Send us your writing, photography, or artwork

- Republish our Creative Commons-licensed content