Less than one year after Gavrilo Princip assassinated Franz Ferdinand, archduke of the moribund Austro-Hungarian Empire, the American journalist and future Red army fighter, John Reed, set off for the Balkans with likeminded, and sometimes controversial, political cartoonist Boardman Robinson to cover the war Princip had sparked: World War I.

Since Reed and Robinson published their illustrated history, The War in Eastern Europe, a historical consensus seems to have emerged that of all the soldiers who fought in all the world’s wars, those who fought in World War I were the most confused about what, if anything, they were fighting for. While Princip himself may not have known why he had been instructed to shoot the archduke, aside from the pressing matter of removing the term “archduke” from the Austrian lexicon, his superiors certainly did. The leaders of the Black Hand — Bosnian Serbs tired of Catholic Austria-Hungary’s vicious rule, and envious of neighboring Serbia’s independence — agreed that Ferdinand’s death would expedite the creation of Yugoslavia, a national home for the South Slavs.

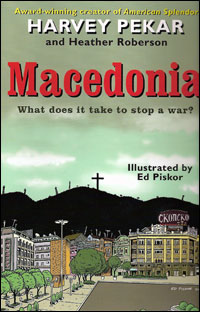

Nearly a century later, the Black Hand’s accomplishment undone and the republics that briefly comprised Yugoslavia again plunged into war, Harvey Pekar, Ed Piskor, and Heather Roberson take up where Reed and Robinson left off in their graphic novel, Macedonia: What does it take to stop a war? — written by Roberson, illustrated by Piskor, and orchestrated by Pekar.

While Reed covered the Balkans after people “had settled down to war as a business, had begun to adjust themselves to this new way of life,” Roberson wants Macedonia to give people “a firm idea about what peace is.” Pekar similarly describes the book as having an opposing agenda. “There isn’t any fighting going on. There are disagreements, but people aren’t shooting at each other.”

A motivated, Gandhi-admiring student in University of California, Berkeley’s Peace and Conflict Studies Program, Roberson met Pekar by chance in 2003, when her sister invited him to speak at a showing of American Splendor, a movie based on Pekar’s successful comic book series, in their hometown of Columbus, Missouri. The timing was fortuitous. Roberson happened to be stopping through Missouri en route to Macedonia where, she told Pekar, she planned to spend a month researching why that country did not descend into civil war in the 1990s while the other former Yugoslav Republics — Slovenia, Croatia, Bosnia, and Serbia — did. Intrigued, Pekar asked Roberson to send him some notes that he could use as the basis for a story. “I was expecting to do at most a long short story, maybe 25 to 50 pages,” says Pekar. “But she sent me almost 150 pages of material, and I thought ‘Wow, we could make a book out of it.’”

While Pekar’s earlier work rarely comes across as political, he says he cares “much more about history and politics than people realize.” Indeed, he lectured me authoritatively for 20 minutes, succinctly summarizing Yugoslavia’s history since the archduke’s assassination. When World War I ended four years and many deaths after that fateful event, Yugoslavia was created, he explains. If millions of people had fought and died for naught, at least Princip’s superiors could take solace in the fact that the Yugoslavian nationalists had not.

“When the Second World War started,” explains Pekar, “Germany invaded Yugoslavia and there was all this guerrilla warfare. The most effective guerrillas were led by [Josip Broz] Tito. Tito managed to pull Yugoslavia together, to pull all these ethnic groups together who had a lot in common with each other, but who, nevertheless, had been fighting each other for God knows how long.”

Tito’s Yugoslavia was communist but unaligned, undemocratic but relatively free, and — despite ethnic and religious variety — united. But after Tito died in 1980, the common identity he had managed to instill in, or force on, the Yugoslavian people began to fade away. When the new leader, Slobodan Milosevic, tried to reimpose that identity (albeit with less popular support and less skill than his predecessor), local nationalisms were awakened and civil wars broke out. Macedonia, with its large Albanian minority and weak central government, was a prime candidate for violence. Surprisingly, some might say, war never broke out.

Roberson is a firm believer in peace, but it does seem remarkable, given the unwavering pessimism with which journalists, scholars, and Macedonians alike prophesied Macedonia’s demise after its secession in 1991, that war never came. In Robert Kaplan’s Balkan Ghosts, the editor in chief of Macedonia’s largest daily newspaper is quoted as saying, “This is the most volatile area of the Balkans. We are a weak, new nation surrounded by old enemies. Several nations could come to war here as they did at the beginning of the century … And don’t forget that we are a quiet Kossovo: twenty three percent of Macedonia’s population is actually Albanian … We face the same fate as the Serbs in their historical homeland.”

Perhaps it is this fear that makes Macedonians so nostalgic. As one woman tells Roberson, Yugoslavia “was wonderful. Just traveling was so different then. We could go wherever we wanted. We used to go to the beach in Croatia … I was very young, but yes, I cried at his [Tito’s] funeral. Everyone was devastated.” Surprising or not, the avoidance of war in Macedonia proves Roberson’s point: What is needed to prevent a civil war is that “people within the country and in the international community make a commitment to peace and diplomacy as a strategy.”

For Roberson, peace does not necessarily mean harmony. It may actually entail conflict, which she sees as a good thing. “Conflict is how we learn,” she says, “it’s how we uncover problems in our own way of thinking.” Despite being a tiny country of barely 2 million people, Roberson insists, Macedonia’s case is applicable elsewhere, even to larger countries with valuable natural resources. Pekar adds, “Macedonia shows that if you can ever get international cooperation, a lot of things could be accomplished. Right now, there’s very little cooperation.”

A graphic novel whose illustrations are both immensely comical and brutally honest, especially in their depiction of prejudice, Macedonia is much more than a lesson in political optimism. Perhaps Pekar’s disillusionment with the standard superhero comic — which he had grown sick of by age 11 — and his desire to break away from the arbitrary limits imposed on the graphic novel as a medium, make him underestimate the humor inherent in this book. “Some parts of Macedonia are funny,” he admits, “but basically, I saw this as a serious project and I didn’t have any problem with that. Just because it’s never been done doesn’t mean it can’t be done.”

But scarcely a page lacks an image or anecdote worthy of a hearty chuckle. The existence of a Bill Clinton Street in Kosovo, for example, is very funny, as is the anecdote about a policeman who pulls over an international worker because he mistakenly believes a dog is driving his car.

Amusing, informative, and often compelling, Macedonia fits into no preexisting genre; its format serves its purpose effectively. Roberson explains, “A graphic novel is a great way to tell a story that has so much to do with geography, so much to do with where a place is and who lives there.” Even more so when the story concerns Yugoslavia, a historical labyrinth that not even Borges could have concocted. Boasting “the most frightful mix-up of races ever imagined,” as John Reed put it, Yugoslavia’s constantly changing names and boundaries, regular population transfers, and wealth of religions and alphabets render the Macedonian situation entirely inseparable from Yugoslavia’s sprawling history. This book serves as “a primer, something that is as accessible as possible, but that has the history people need to know in order to understand Macedonia and why it was so exceptional for dealing with its conflicts peacefully,” says Roberson.

The huge cross that sits atop a hill overlooking Skopje and reminding Muslim Albanians that they are not in charge; the segregation between ethnic Albanians and Macedonians; the rumors of Macedonian doctors who poison Albanian children — these are not exactly signs of a harmonious society. But in the same country, citizens plaster billboards with antigun posters; graffiti declares “war is bad for your health”; NATO troops peacefully disarm militias; nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) listen to Albanian grievances and pressure the Macedonian government to consider them; and young people set up a multiethnic university. Only segregation has found its way into history books, but it’s been the antiviolence campaigns and the cooperation that have ultimately triumphed; it is these symbols that should be recorded as phenomena of historical significance.

Macedonia is a valiant attempt to set history straight. Roberson, Pekar, and Piskor have created a moving and memorable book that has revolutionized the art of the comic and has the potential to alter the long-dominant discourse on war.

Visit jeremygillick.blogspot.com for the full interviews.

- Follow us on Twitter: @inthefray

- Comment on stories or like us on Facebook

- Subscribe to our free email newsletter

- Send us your writing, photography, or artwork

- Republish our Creative Commons-licensed content