Click here to enter the photo essay.

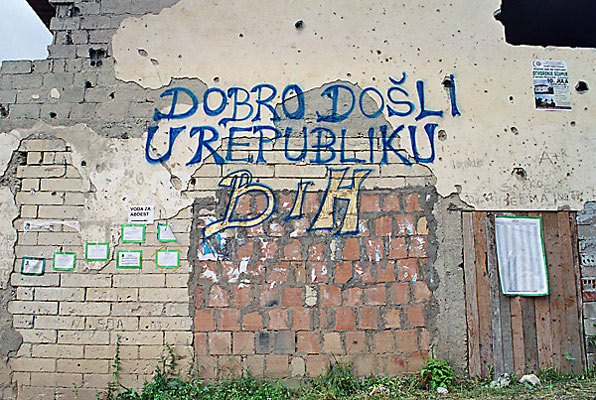

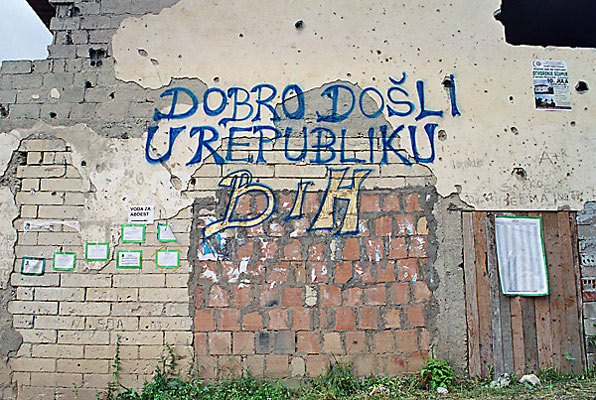

Between July 12 and 16, 1995, up to 8,000 Bosniak men and boys were killed by Bosnian Serbs under the command of the indicted and still at-large former General Ratko Mladic. July 11, 2005 marked the ten-year anniversary of the massacre. On that day, 610 victims of the Srebrenica massacre were buried at the Potocari commemoration center in the Serbian Republic of Bosnia-Herzegovina.

There was a time when I was afraid to look at these photographs.

I developed them at the end of August, after a summer of reporting in Bosnia-Herzegovina. Though images from the Srebrenica commemoration still intermittently flashed through my mind without warning — bullet-punctured skulls in a mass grave, an old man sobbing and clutching his grandson’s coffin as it was lowered into earth — the thought of looking at them seemed somehow more threatening than my fractured, yet fierce, memories.

For several days they sat on my desk, bulging in their sealed envelopes. Could I bear to face what I’d experienced? I didn’t know how to make sense of it myself, and nothing and no one had helped so far. And of course by now the newspapers had no mention of Srebrenica, as if the real story was a one-day ceremony and not the daily lives of people in the area — Bosniaks, Bosnian Serbs, returned refugees, family members of victims, and victimizers.

After the commemoration, friends and I drove through the winding roads of the Serbian Republic and back to Sarajevo. Around 1am I arrived in Bascarsija, the historic Ottoman section of the city where I was living, and phoned my parents. “You don’t know what I’ve seen!” I told my father. “I won’t be able to sleep. I saw a father jump into the grave of his son who’d been killed … How can I forget this?”

I told him I was sure I’d have nightmares that night and every night afterwards. “You won’t dream about it,” my father assured me. He was right. Instead, images flickered through my mind during unpredictable times of the day: the lyrical, cyclical movement of coffins as men passed them from hand to hand to hand; the despairing duplication of rows of green shrouded caskets lying in the old battery factory where the Dutch troops were headquartered in 1995. At other times, phrases, not pictures, jarred me back to the experience: the comment of a young Bosnian Serb woman living in Srebrenica — “It’s hard to live here because it’s hard to always live between the past and the future,” or the refrain often heard from those whose family members were killed — “We don’t need a commemoration — all we want are our relative's bones.”

When I finally looked at my photographs, I was shocked by how innocuous they were. I’d had nothing to fear. Everything was so inappropriately static and calm. The images of the mass grave we visited just outside Potocari didn’t reveal the haunt and hush as it was unveiled. Missing, too, was the tremulous voice of the translator for President of Bosnia Herzegovina’s State Commission for Missing People, Amor Masovic, as he told us the shattered vertebrae and bones we were looking at were approximately 50 of those “who never made it” as they fled Srebrenica for Tuzla. Masovic then soberly explained that almost all these bodies were incomplete. The remains of each individual might be scattered throughout multiple graves. It could take years to make positive identifications and inform victims’ families.

The wide angle shots of the commemoration couldn’t capture the cacophony of disparate yet interconnected sounds: the dzenaza (funeral) prayer, whose final lines implored, “That Srebrenica / Never happens again / To no one and nowhere!”; the whir of European Union Force helicopters circling above, monitoring the events on the ground; the muffled, crackled voices of officials as they condemned the massacre, one after another. No image could convey how the mist hovered over the lush surrounding hills like uneasy, heavy spirits, ready to descend — hills that almost certainly contain more scattered remains of those massacred around Srebrenica.

There was a moment during the commemoration when I and the Serbian journalist with me put down our cameras to offer tissues to a woman with tears streaming down her face as she bailed rain water out of her son’s still-empty grave. I had the humiliating realization that this was perhaps the most significant thing I had done that day.

Are these photographs evidence of witness bearing, or merely being there? I’m still not sure. To me they are merely a reminder of the importance of looking, and of remembering — and understanding the complex responsibilities that accompany both.

- Follow us on Twitter: @inthefray

- Comment on stories or like us on Facebook

- Subscribe to our free email newsletter

- Send us your writing, photography, or artwork

- Republish our Creative Commons-licensed content