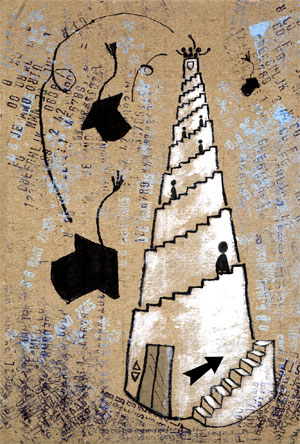

(Illustration by David Benque)

Cold, drenched, and hanging from a telephone pole on a rainy March day 16 years ago, Cathy Mulder decided she’d had enough.

Mulder had been with the telephone company for 11 years and was active in the union. This was her sixth year as a cable splicer, a dangerous but well-paying position she landed after filing numerous gender discrimination complaints.

“I found myself hanging from a pole and decided I could do more for workers than getting soaked,” says Mulder, a 46-year-old labor studies professor with a straight-shooting Jersey accent. A year after the revelation on the pole, the Teaneck, New Jersey native quit her job and went back to school full-time. Two years later, she graduated summa cum laude from Stockton State College with a bachelor’s degree in economics.

Spurred on by her Stockton State professors, Mulder went on to do something she never thought she would do: She enrolled at Temple University and started pursuing a Ph.D. After two years at Temple, she took a terminal master’s and transferred to the University of Massachusetts to finish her doctorate. She has passed her comprehensive exams and is now completing her dissertation.

While race and gender diversity among university faculty and graduate students has increased substantially in recent decades, class diversity has lagged behind, making stories like Mulder’s less than typical. Many working-class academics say it is still unusual to find a Ph.D. colleague who is not the child of a doctor, lawyer, corporate executive or other middle-class professional. Working-class Ph.D.’s have written papers, dissertations, and even books about feeling out of place and misunderstood in the ivory tower.

Since for most fields, graduate school is the only route to becoming a professor, class bias within doctoral programs must necessarily translate into a bias in faculty hiring. But trying to get a statistical handle on that bias is nearly impossible. None of the organizations contacted for this article — the National Center for Education Statistics, The College Board, and UCLA’s Higher Education Research Institute (HERI) — could provide statistics on the class backgrounds of graduate students. Information on faculty class backgrounds is also tough to find. However, the studies that do exist indicate, as expected, a strong middle-class bias among the nation’s professoriate.

When Seymour Lipset and Everett Ladd analyzed the results of the 1969 Carnegie Commission on Higher Education Faculty Survey in their 1979 paper “The Changing Social Origins of American Academics,” they found that roughly 60 percent of the fathers of the over 60,000 survey respondents came from professional, managerial, and business backgrounds, while only 25 percent were “of working-class origin.”

Looking at faculty makeup in the 15 years following the Lipset and Ladd study, researchers Joseph Stetar and Martin Finkelstein reported in 1997 that the percentage of faculty from professional and managerial-class families had scarcely changed between 1969 and 1984, although the class demographics of university students changed “significantly” during that time to include more students from low-income families.

In 2001, Kenneth Oldfield, an emeritus professor of public administration at the University of Illinois at Springfield, and Richard Conant from the Southern Illinois University School of Medicine, conducted a small-scale survey of the faculty at a Big Ten university. Over half of the 567 professors who responded said they had parents who were doctors, lawyers, or other professionals. Less than 2 percent of the respondents said their parents had jobs in the lowest 20 percent of the socioeconomic scale, in fields like farm work or dry cleaning.

What education destroys

Many people who identify themselves as working-class cite a family history of jobs involving manual labor, service work, and rock-bottom pay. Some, like Mulder, have earned a good living working with their hands. However, the social status of a well-paid manual laborer can be quite different from that of a well-paid white-collar worker.

Growing up, Mulder used to accompany her father, a plumber, to his weekend jobs. She says that although he earned as much or more than many of the people in the suburb where she grew up, she was “treated differently” because she was a plumber’s daughter.

For Mulder, being working class is about more than money. It is about knowing how to “get your hands dirty,” something she thinks many Ph.D.’s have little experience doing.

Carolyn Law is an editor with fellow working-class academic, C. L. Barney Dews, of This Fine Place So Far From Home: Voices of Academics from the Working Class, a book that features narratives of scholars from working-class and poor backgrounds. She observes, “For poor and working-class people, access to higher education is all about class.”

In This Fine Place, Law and Dews examine the “oxymoron” of the working-class academic label. In theory, earning a Ph.D. should propel a person into the middle class. It is not that simple, however. A college degree does not change a person’s past, and many working-class intellectuals feel deeply connected to their blue-collar roots.

Law still remembers the conversation she had years ago with her mother, a widow who worked a number of low-paying jobs to keep the family going after her husband died. “Education destroys something,” she told her daughter. Law agrees. “It was a break, and it did break something,” she says.

“It comes out in the way I talk. I can hear myself as different from my family now.” To illustrate her point, she contrasts what she calls her “higher education-educated accent” with the Ozark hillbilly twang of her relatives.

Law did graduate work in modern literature at the University of Minnesota, but left the school to pursue a full-time editing career. Her most shocking encounter with class in the classroom occurred while she was an undergraduate in Missouri. The professors in her education courses often talked about “at-risk” children — kids who have no books at home and whose parents do not read to them. Such kids, they warned, would always be a “problem” in the classroom.

“They kept painting this picture of a culturally deprived and deficient home that created this culture of at-risk children,” Law remembers. “And I was one of them.” That was the moment when she concluded that “to be valued in society, I’d have to shift my allegiance. I’d have to buy into the professors’ message, and turn a very critical eye on my home life.”

Law, who was raised in a home with no books, said the professors’ words made her ashamed and ambivalent. “You, on the one hand, hate your past, but want to defend it,” she explains. Her experience might explain why it is so difficult to pin down numbers of working-class Ph.D.’s. Scholars who study the class dynamics of academia use the phrase “class closet” to describe the mentality of Ph.D.’s from working-class and poor families who refuse to talk about their class origins out of fear that their middle-class colleagues will look down on them.

Hidden bigotry

Some working-class Ph.D.’s, like Marjorie Gurganus, think their professional progress has been hindered by middle-class colleagues who buy into negative class stereotypes. Gurganus is a law student who spends her spare time doing pro bono tax work in low-income communities. Before starting law school, she earned her Ph.D. in genetics at North Carolina State University. Her father made his living as a factory maintenance worker while pursuing his law degree at night. Though he eventually finished law school and set up his own practice, he never made much money as a lawyer, and the family still qualified for food stamps.

Gurganus, who worked at McDonald’s for two years while in high school, recalls one Ph.D. who would make fun of her for having worked at a fast-food job. She says that, instead of being impressed by her hardscrabble skills and work ethic, ”He was just horrified” and viewed her as “a contamination” in the lab. She thinks academics from working-class and poor backgrounds take a professional risk when they talk to colleagues about past jobs or problems with money. “Some of them have always worked in a nice, clean place that was always advancing their career,” says the Jacksonville, North Carolina native, who did her undergraduate work at Cornell University. She thinks some middle-class Ph.D.’s have trouble relating to people who have to “deliver pizzas for eight dollars an hour rather than work in a lab for five” just to make enough money to buy groceries. “They start viewing you as someone who has these problems,” she says.

Gurganus left the genetics field in part because she was unsuccessful in landing a position as a professor, a circumstance she feels was partly related to her class background. She describes the Ph.D.’s she was competing with as “more established.” She says many of them already had the standard middle-class accoutrements — “a home, a couple of cars, a stable family, hobbies” — in addition to strong scientific backgrounds. Gurganus believes that, when choosing among candidates with near-equal academic credentials, middle-class professors have little incentive to hire someone from the working classes. She sums up the mindset this way: “If there are several of you who are smart, why take the one who doesn’t have the same background as me?”

Blue-collar bonding

There is an irony inherent in academic elitism. After all, school is supposed to help level the playing field for people from economically underprivileged backgrounds. Students from working-class and poor families often expect a college education to increase their professional options and provide them with opportunities that their parents did not have. When that optimism butts with class realities, the effects can be painfully disillusioning.

Barbara Peters is a working-class academic from Oshkosh, Wisconsin, who teaches sociology at Long Island University’s Southampton College. “When you’re brought up in working-class and poverty-class situations, you’re taught that education is the ticket out,” she says. “It’s like Nirvana: You’re going to go to college, and your life is going to change. So you’re kind of idealistic.”

Acknowledging that a degree doesn’t offer the access it seems to promise, in 1993, Peters founded an online support group called Working-Class Academics, where professors, Ph.D. students, and independent scholars can discuss what it feels like to be working-class in academia. The group, which started with just 25 members, now has between 250 and 300.

“It’s probably the thing I’m most proud of in my academic career,” says Peters, whose mother was a school cook.

Not everyone is impressed by her activism, however. Peters’s views were once challenged during an online discussion with fellow intellectuals. One person criticized the concept of class labels, saying that people change classes throughout their lives. The same person said that she herself had chosen to be working-class by taking a job as a waitress.

“If you chose to be working class, then you aren’t working class,” Peters replied. That exchange prompted Peters to start the Working-Class Academics list.

Peters, who walks with crutches due to a degenerative arthritis condition, points out that being disabled adds another dimension to her concerns about discrimination. She also notes the challenges faced by women and people of color in the academy. “It’s a matrix of oppression,” she concludes.

Despite the criticism she has faced (some have called her a “reverse classist”), Peters is determined to keep reaching out to working-class intellectuals. “We are here. It would be wonderful if people from the upper classes would listen.” Citing growth in the Working-Class Academics list’s membership, she adds, “I think there are more working-class academics out there than we’d even realized.”

Money too tight to mention

While in graduate school, Amy Feistel worked multiple research assistantships to avoid taking out loans she knew she could never repay. She says she was criticized for spending too much time at work and not enough time on her studies. She remembers one scholar telling her that she was “not cut out for academic work” and would “be better as support personnel than as a scholar.”

Such comments did little to bolster Feistel’s image of herself as an academic. “I felt like I was not provided with the appropriate support to build the analytical skills required to be a scholar,” she says.

Feistel, whose parents struggled to support five children on modest missionary salaries, did graduate work in cultural politics at a top-ranked university. Her family history reveals a mix of classes. She describes her father’s relations as upper-middle-class and college educated, “with well-provided, secure futures.” Relatives on her mother’s side, however, have always had financial problems, often raising large numbers of children on low military salaries.

While Feistel appreciates the support she received from some of her professors, she insists that “one or two people hardly make up for a difficult system.” She adds, “I have always been forthright about my circumstances, but have found the circumstances often make others uncomfortable.”

For working-class academics with few financial resources, the economic obstacles to graduate education begin long before the courses start. “It’s just difficult at every step of the way.” says Paige Adams, who holds a Ph.D. in neuroscience from Baylor University. She had to scrape together nearly $100 just to take the GRE, a large investment for a woman who waited tables, taught aerobics, and took out $35,000 in loans to finance her undergraduate degree at the University of Houston. She handwrote all of her applications to graduate school because she could not afford a computer. To make matters worse, some of the schools to which she applied did not offer application fee waivers.

“This whole idea that you have to have all of this money upfront puts aspiring working-class scholars at a disadvantage from the start,” Adams insists.

Most Ph.D. students put up with long hours and low pay as teaching and research assistants. However, Adams thinks those from working-class and poor families have it especially hard. “Most people I knew in graduate school had parents that helped them out,” she says. “There weren’t a lot of students there from poor families.”

Feistel remarks, “Working-class academics face the usual issues that all academics face, but I believe the issues are exacerbated by the concerns for daily living: income, housing, food, transportation.”

Jennifer Gibbons, a pharmacology Ph.D. student at Duke University, relates, “I find that many people here in graduate school went to private high schools, or at least large schools where they had the opportunity to have honors classes and take Advanced Placement tests.” Her own high school offered “no real honors classes” and only one AP test: English. The Indiana native continues, “I feel as if I had very many lost opportunities at my school, but had no choice — my parents couldn’t afford to send me anywhere else.”

Carol Williams, a professor of Women’s Studies at the University of Lethbridge in Alberta, Canada, felt similarly disadvantaged coming into graduate school. “Poor results on the GRE is perhaps where I felt most disabled coming to graduate school initially,” Williams recounts. “I felt I came to the exam already lacking basic skills. No account is taken in standard testing for cultural or economic differences, and I feel this favors not only Caucasians, but those from wealth.”

A different world

Sociology professor Michael Schwalbe relaxes in his paper-packed office where a poster for his book, Remembering Reet and Shine, a biography of two working-class African American men living in the South, hangs near the door. Sporting shorts and sneakers, he talks about his journey from Boys Technical School in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, to North Carolina State University in Raleigh. “I haven’t pursued my career in a conventional way,” says Schwalbe. On his way to becoming an academic, Schwalbe worked as a mechanic, a bartender, a music promoter, and a nature writer.

He calls his decision to buck family tradition and pursue a non-vocational path “risky but freeing,” though he admits he was a little lost at first. “I didn’t know what you do to become a professor.” When he decided to pursue his Ph.D., he considered only two schools: Washington State University for its natural surroundings and the University of Texas at Austin for its folk rock music scene. That way, he figured, if the sociology path did not work out, he could easily pursue one of his other passions. He did not even consider applying to the prestigious University of California at Berkeley, though one of his professors urged him to do so. At that time, Schwalbe had no concept of what he calls “the prestige factor,” and how going to a school like Berkeley might influence his professional future.

Most of the working-class Ph.D.’s interviewed for this article say they grew up knowing much less about the academic world in general than their middle-class peers. “You mean there’s school after this school?” was working-class academic Beverly Rockhill’s reaction when her undergraduate cohorts at Princeton started talking about doing a Ph.D.

The language of academia shocked Jodie Lawston more than anything. “They were talking very theoretically and using language I had never even dreamed of,” recalls the sunny-voiced Long Island native. She describes the students in her graduate program as being from wealthy families and “worlds ahead” in terms of vocabulary. Lawston found their theoretical lingo intimidating at first, but now pokes fun at the bulky phrases. Her answering machine greeting instructs unsuspecting callers to leave their name, phone number, and “a brief ontological explanation of women’s existential dilemmas.”

“The academy is a place for ideas and not for activists.”

During one of her graduate seminars, Lawston suggested that scholars put social theory into practice. According to her, a classmate erupted, “The academy is a place for ideas and not for activists.” Lawston was stunned. She later heard a similar comment from another colleague.

Lawston, whose father is a construction worker, grew up having to deal with things like the phone being disconnected and the heat being cut off in the middle of the winter. “We were not philosophizing at the dinner table,” she laughs. She thinks some of her middle-class counterparts take a hands-off attitude toward social activism because they have not had to do without basic necessities. “Even though they study classism, that’s all they do — study it.” she says. “They don’t really struggle with it.”

Working-class academics themselves struggle with it in different ways. Monique Lyle, a Ph.D. student in Duke University’s political science department, remembers being “really class-conscious” when she began her studies at the elite school. But for Lyle, class has always been a question of both money and race. “In a lot of ways, class distinctions are along racial lines,” notes Lyle, who is black.

Jason Allen, an assistant research professor at Duke, came to the United States from Barnsley, England, and earned his doctorate in exercise physiology from Louisiana State University. He lives with his pal, Gordon, a tomcat who paws for attention during our phone interview. Allen sums up the difference between the United States’ and England’s ideas about class this way: “In England, they care where you came from. In America, they care where you’re going.” Allen thinks American class distinctions are based more on money than birth, but, like Lyle, he also believes those distinctions are impacted heavily by race.

Allen, whose mother works in a bakery factory, has found that many American academics hold British people in high regard. He believes the Yorkshire accent that might have hindered his professional advancement in his native land actually worked to his advantage here in the States. “I moved from working-class to upper-middle class in the blink of an eye,” he says.

The discomfort of straddling

Several working-class academics speak of feeling torn between the world of their families and that of their peers. Carol Williams had a tough time explaining her academic ambitions to her mother. “When I was raising money to attend my program in a master’s degree in England, she stated, ‘Why all this trouble and pain to get a few letters after your name?’” Williams recalls. “She didn’t comprehend the motives for advanced education, nor did she understand what exactly we did there.”

Lyle has had similar troubles. “[My mom] thinks I talk like a white girl,” she laughs. Though she has a strong relationship with her family and loves going home, she does not think they have a real sense of what she does. She feels removed from her extended family and worries that she does not fit in with the black working-class community where she grew up.

Despite the challenges they face, most of the working-class Ph.D.’s interviewed say they benefited from going to graduate school. “I just had a great graduate school experience,” says Adams. “I had a great job, a great boss … It just felt like a family. I made a lot of good friends.”

Like Adams’, most of Mulder’s experiences in academia have been positive. Still, Mulder admits, “I don’t know anybody else like me.” Mulder now teaches labor studies to workers and unionists at a satellite campus of Indiana University, a job she got in part because of her unusual life path. “That’s precisely why they hired me,” she notes. “There are not too many Ph.D.’s that know how to be a worker.”

The hybrid advantage

The same family relationships that can complicate a working-class Ph.D.’s relationship to academia can also be a vital source of support. In working-class families where no one has attended college, there is often a sense of vicarious accomplishment in watching one of their own go all the way.

Paige Adams’ mother has been her biggest cheerleader, urging her to pursue the college education she herself always wanted. “She always felt that she missed out by not going to college,” says Adams.

Jodie Lawston thought of dropping out many times during those first few years of graduate school, but her mother’s words helped her stay the course: “You gotta do it ‘cause we never did.”

In the end, having a foot in both worlds might be one of the working-class academic’s greatest assets. “I’m resigned to a sort of hybrid status, which, as I grow older, I recognize gives me a unique and under-represented intellectual perspective on many issues,” Rockhill says.

Feistel, who now works in educational administration, says her experiences have made her more understanding of the challenges facing working-class students. “I’m in a better position to understand a working-class student,” she remarks. “I’ve been on both sides of the system, and I know how the system works.”

“Mostly what makes me different is a consciousness of what work really means,” adds Law, whose father made his living digging basements with a bulldozer. “To hear some tenured professor talk about their work environment like they’re some kind of miner … it really hurts me.”

Other working-class academics, like Schwalbe and Allen, say their life experiences have made them extremely adaptable. “You can move in almost any environment and function with almost any group of people,” says Allen.

Jodie Lawston, who felt “so inferior” to her middle-class colleagues when she started graduate school, now views her working-class background as an asset. “I think it gives you a stronger perspective on everything. I think you’re able to relate to people better,” she says.

STORY INDEX

ORGANIZATIONS >

Working Class Academics List

URL: http://www.workingclassacademics.org

MARKETPLACE >

Purchase this book through Powells.com and a portion of the proceeds benefit InTheFray.

This Fine Place So Far From Home: Voices of Academics from the Working Class by C.L. Barney Dews (editor) and Carolyn L. Law (editor)

URL: http://www.powells.com/cgi-bin/partner?partner_id=28164&cgi=product&isbn=1566392918Strangers in Paradise: Academics from the Working Class by Jake Ryan and Charles Sackrey

- Follow us on Twitter: @inthefray

- Comment on stories or like us on Facebook

- Subscribe to our free email newsletter

- Send us your writing, photography, or artwork

- Republish our Creative Commons-licensed content