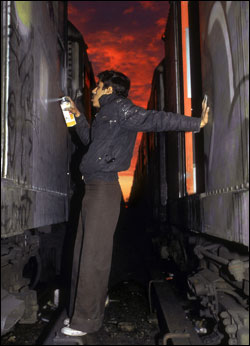

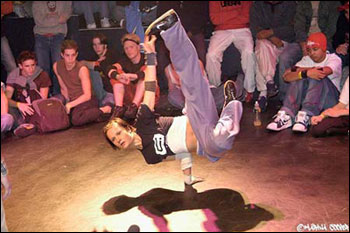

From the time Martha Cooper received her first camera — a Baby Brownie — while still in nursery school, she has been in love with photography. Sixty years later, Cooper is a renowned documentary photographer based in New York City. She worked for the New York Post as a staff photographer from 1977 to 1980, but she is best known for her pioneering work in the 1970s and 1980s, documenting the emerging hip-hop scene. Her book Subway Art (Thames & Hudson), published in 1984 in collaboration with Henry Chalfant, raised subway car graffiti to an art form and is still considered a classic text for graffiti artists today. In 1994, she published RIP: Memorial Wall Art (Thames & Hudson) that showcased the practice of spray-painting murals on city walls and subway cars to commemorate recently deceased friends and relatives. Since then Cooper has collaborated on many other projects that portray little known aspects of urban folklore. Her latest book (together with Nikki Kramer) is We B*Girlz (PowerHouse Books, 2005) about female break-dancers. Cooper recently talked with former ITF Travel Editor Anju Mary Paul about her projects past, present, and future, the increasing appreciation for urban culture in New York today, and the difficulties of getting published. But first, we had to convince Cooper that she was an activist.

The Interviewer: Anju Mary Paul

The Interviewee: Martha Cooper

I’m active; I don’t know if I’m an activist. It’s a subtle form of activism that I do — it’s not like picketing. Do you know about Citylore? I’ve worked for them for 20 years. They’re a non-profit community organization that documents, among other things, the ethnic communities, festivals, arts, traditions, and urban folklore of New York City. This is their 20th year and I’ve been involved with them as director of photography for the entire time.

Did you become interested in Citylore because your own interests are so closely aligned with urban culture?

Yes. I did an early project on “play” which evolved into a book called City Play. That sort of led to my introduction to Amanda Dargan and Steven Zeitlin, who had similar interests and then they founded Citylore. They do poetry gatherings, public programs; it’s not just photography. Their mission statement reads: “As cultural activists we are committed to the principles of cultural equity and democracy. We believe that cultural diversity is a positive social value to be protected and encouraged; that authentic democracy requires active participation in cultural life, not just passive consumption of cultural products; and that our cultural heritage is a resource for improving our quality of life.” So, yeah, I guess I’m a “cultural activist.” Let’s go with that one!

How did you get into this field in the first place, connecting photography and urban culture?

I grew up with photography because my father had a camera store. And I wanted to travel. As soon as the Peace Corps was formed, I joined. I was in the Peace Corps in Thailand from 1963 to 1965. Then I decided I liked traveling around and looking at different cultures. I wanted to be an anthropologist. So I did a year of graduate work and then decided that I really didn’t want to be an anthropologist! It was too analytical. I just wanted to look at the stuff, take pictures and things. So I decided I wanted a job that would combine photography and anthropology, but there really wasn’t a good path to do that at the time.

So you pretty much created the job for yourself?

I did. Of course, there is a history of ethnographic photography. And there are actually some books on it. And now I think there’s even an organization: Visual Anthropology, but I haven’t followed what they’re doing.

Did you start taking photos of urban culture through your job at The Post?

I was very attracted to New York City for no reason I can put my finger on. I knew all the publishers were here and I wanted a career in photography. At the time I was living in Rhode Island, but the things I wanted to photograph fell more in the category of “urban folklore,” so when I came to the city, I naturally sought out the things that interested me and took pictures of them. And then I found out that there is a field of urban folklore, so I connected with those people who were doing research in this field. A very early project I did was called “Brooklyn Rediscovery.” We produced a slim little pamphlet Making Brooklyn Home that we are constantly going back to for information about these places. It covered typically urban and New York City things like pigeon flying, playing bocce but using old railroad tracks under the El as opposed to a court, playing skelly, which is a game only played in New York City, and the giglio (pronounced jil-i-o) festival in Brooklyn, which is still going on. We did extensive research with urban folklorists on this project. There’s a core group of folklorists in the city and I kind of fell into it and that’s where I still am.

Do you find that interest in urban folklore within New York has grown since you first started?

Yes. I think that people are much more aware and so I don’t shoot it as much anymore because I don’t like to go to these festivals and find hundreds of photographers there. When I was the only photographer, I felt I was discovering something interesting and unusual, and preserving it. Photography is a great way to preserve history. It’s cheap and one person can do it; you don’t need a film crew. But now, when I go to many of these festivals, I just feel like I’m elbowing other photographers. In a way, that’s a good thing. It means that New Yorkers are more aware and participating in cultural activities that are out of their own culture. But I like to be the discoverer.

Do you find yourself moving more overseas to do projects? Is the U.S. maxed out?

I don’t want to go overseas to do projects. What I found is that even though it’s a lot of fun to travel, it’s too hard. It’s hard to do a continuing project and connect with people and be able to go back. I’m always arriving and being told, “Oh, you should have been here last week! That’s when we really had the big thing,” or “Wow! It’s coming up next week,” but I’ve already gotten my ticket home.

What projects are you working on now?

There’s a neighborhood in Baltimore called “SoWeBo” — South West Baltimore — after Soweto in South Africa. The name of it appealed to me as much as anything else. And I found a little house there. There are no stores, there are no Starbucks; it hasn’t gentrified yet. There’s a liquor store, I think. But I met this couple and they said, “We’re going to make this place into Georgetown!” And all this is right on my street. A block away there’s one of the oldest stables in America. They have 18 horses and they have these guys called “A-rabs”, and they go round the neighborhood with horse carts selling produce. There’s another Baltimore tradition of painted screens. People paint their screen doors and windows so you can’t see in through them. There aren’t that many left; the screen painters have all pretty much passed away, but I did see a few. And this is all in my neighborhood. This is urban folklore in Baltimore.

How do you choose your projects?

Something about it has to excite me in order to invest so much time and money in it. I like to feel that I’m investigating something that hasn’t been extensively covered before, though in the world today, that’s practically impossible. But graffiti was like that, and when I started covering hip-hop, the words weren’t even in use. And I got into that through break-dancing, which I’d never seen before and wanted to pursue. And my neighborhood in Baltimore, I feel that there has not been any documentation about it.

A lot of other projects are just given to me. I do them with somebody because it’s their project, not mine. I’m pretty much a jack-of-all-trades; I’ll do anything. I’m fortunate that I don’t have to go out looking for work; work comes to me. At this point, I don’t even have a portfolio.

Do you have any dream projects in your head?

Well, the Baltimore project is the one that’s kind of taken over my imagination right now. The thing that’s different about Baltimore is that it’s all my own. I’m not working with anybody else; it’s just me so I’m completely free to decide what I want to shoot and how far I want to take the project. There’s no pressure to satisfy someone else; I just have to satisfy myself. And when I get a good picture, it’s very exciting. When I see kids playing in inflatable pools on the sidewalk, I get a buzz! So Baltimore in some ways is my dream project because I can take what I’ve learned in the last 20 years and apply it to a fresh site. There’s nothing like going to a new place to get your juices flowing. But I can also come back to New York easily. It’s like traveling — I call it my “country house” even though it’s very urban. Going there evokes the same kind of joys of traveling, but without the inconveniences. I can go back and forth. For instance, I was in Baltimore for the past three days, I came back here for two days, and tomorrow I’m going there again.

There are other projects that I would like to do. For instance, I lived in Japan for a couple of years in the 1970s. And I’m trying to put those photos together into a book. I have enough photos for a hundred projects. So I’m now thinking I should start to put them together.

Has it been hard at times to get other people interested in the projects you’re interested in?

Yes. It’s definitely hard to get them published. For instance, for years I’ve documented vernacular architecture. I have huge files on vernacular architecture in New York that I have on my computer. And I’ve had all kinds of book proposals out and I’ve gotten grants to do this, but I’ve not been able to get a publisher. And when you look at architecture books in stores and you see all this formal architecture but there’s not even one book on urban vernacular structures. My photos have to do with surviving in the city and finding interesting ways to ply your trade without spending a lot of money; for example, by squeezing a tiny store between buildings. And there’s all kinds of personalized things: door-handles, signs, awnings, and menu holders. There are many different ways that individuals transform the city. That’s my theme. But I’ve just not been able to get anywhere with this in terms of publishing it. My idea was to simply publish it as a little book similar to the one I did on memorial walls. And I have contacts with publishers — it’s not like I’ve never been published. But they just look at it and say, “Nah, won’t sell,” but I think it would sell. I just think that people walk up and down the street and they don’t notice these things.

I remember you told me how much trouble you had getting Subway Art published.

Exactly. But when I did get it published, the same publisher published Memorial Art and I would have thought—it’s an architecture publisher—that I would have been able to talk him into this one too. But I have not been able to get anywhere. What I’ve decided is that the longer I wait, the more interesting these photos become as the city changes. Most of the structures are already gone. It’s hard to get these projects out there. And if they’re not published, what’s the point really? I shoot for my own pleasure of course, but to me, a project isn’t really successful until it’s in some form that is tangible and public.

- Follow us on Twitter: @inthefray

- Comment on stories or like us on Facebook

- Subscribe to our free email newsletter

- Send us your writing, photography, or artwork

- Republish our Creative Commons-licensed content