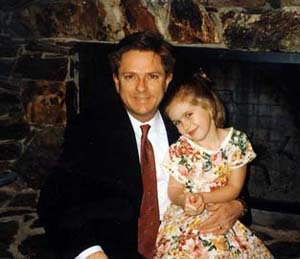

For a little girl, I had many big questions while growing up. My mother usually recommended I write them down, so I wouldn’t forget, and then ask my father. No matter my age, my father always treated my questions with awe and philosophical fascination. I remember sitting in our downstairs living room — the one without the TV — me in my pajama set with my wet hair freshly combed, while my father sipped a glass of red wine. I’d feel so grown up, my mom in their bedroom, my younger sisters already upstairs asleep, and my father and I speculating.

I’d ask him greedily: What happens when we die? Do animals have feelings? Does he prefer to be awake or asleep? He’d tell me he secretly wondered if our whole universe was just a cell on the body of a giant creature — the moon an amoeba. I’d ask him if time really exists because sometimes it didn’t seem to. His eyes would widen while the skin around his brown eyes, the same ones I have, would stretch as he spoke and listened.

I’m sitting at a coffee shop, still heartbroken over my father’s death four and half years ago. I’m trying to write, pursue my dreams and all, because my father would have liked that. Yet, I can’t write because an elderly, plumpish man without much hair is distracting me with every lift of his silver eyebrows. He looks nothing like my wavy-haired, spirited father, but something about his eyes, or maybe the thin skin around his eyes, reminds me of him. I try not to stare at this man while he speaks to his friend, but I feel as though he’s flicking pieces of my father at me with every shift in his facial movements. How can this be? It’s like dreaming of my father only to wake up and realize he is dead. Yet, seconds ago he seemed so alive.

It’s trickery for this man to reach into my deepest ache with his eyes and confuse me. I am startled by this man and must remember he’s not my father. And that my father is not here.

I remember getting the call. That particular night I had been studying for a test the next day, books sprawled across my kitchen table. I missed the first few calls, as I had put my phone on silent to concentrate.

When my mother finally got through, she said my father had had some sort of seizure and the paramedics were sending him via STAR Flight to Seton Medical Center Austin. My mother and sisters were driving the hour-long distance. I was already there in the city for college.

I arrived at the hospital before my family, but for more than twenty minutes the doctors wouldn’t let me see him. I paced in the white-tiled waiting room. I wondered if I should have emailed my teacher to cancel my test for the next day. I wasn’t sure exactly what was happening, but I walked around, overwrought that my father could be feeling all alone when I was only a few rooms away.

When I finally did see him, he was talking loudly, but his voice had no variation. He sounded like a robot. He hadn’t had a seizure, but a massive stroke, and his brain was swelling. He kept asking me to squeeze his hand. He wanted to feel his hand on his right side, but he couldn’t because his right side had gone paralyzed.

His left eye darted around, panicked. “Squeeze my hand, Shannon.”

His left eye darted around, panicked. “Squeeze my hand, Shannon.”

“Daddy, I’m squeezing it.”

“Squeeze harder.”

“Daddy, can’t you feel that?”

I try not to look back at the man in the coffee shop. I could hear his voice soften. My father’s voice used to soften. My father had the most booming, charismatic voice. It was also the most gentle. I’d like to stop thinking about my father now. I’d like to write and get on with my life.

Yet against my better judgment, I begin to study the wrinkly face and protruding gut of the man in the coffee shop. My skin begins to radiate heat. I bite my lip and begin typing furiously — about nothing — on my old yellow laptop my father had bought me.

How come this man gets to live? My father was young and healthy. I want his soft voice, not this stranger’s. Why couldn’t it have been the other way around?

Shame breaks my anger down.

This man seems nice enough. I can’t make out what he’s saying, but I hear his voice. Its familiar cadence starts to soothe me. My mind drifts to another memory of my father. I was twenty years old, and for the first time I saw raw despair in my father’s eyes — or at least it was the first time I was able to identify it.

We met for dinner at a small-town Mexican food chain called Margarita’s, halfway between my college and home. My father ordered a top-shelf margarita on the rocks, while I daringly ordered a Negra Modelo to impress him, two months shy of my twenty-first birthday. I wasn’t carded, and my father didn’t even care.

His face wore a hardened look of intensity that scared me. He wasn’t doing well at work. He and my mother were struggling. He wasn’t where he wanted to be, and he said that time was running out. He wanted to be happy, he was fifty-six, and he wanted to do the best with the time he had left, he said.

“Daddy! Stop! Fifty-six is young these days.”

“I have a lot of life to live. I’m not ready to die, Shannon.”

“Well, of course you’re not.”

But he did, shockingly, just one month later.

I wonder if the fatal blood clot that traveled up to my father’s brain had already started clumping then. I wonder if a part of him knew what was coming.

It reminds me of when I visited Wyoming. I walked along several rivers, and occasionally I’d see natural debris cluster together, clogging the waterway. I guess this is what was happening inside of my father, to the point that his brain couldn’t take it.

As the eyes of the man in the coffee shop widen, I see my father clearly. I now understand why this man reminds me so much of him. It’s a very specific facial expression — the same one my father wore when in meaningful conversation, usually about something existential.

As the eyes of the man in the coffee shop widen, I see my father clearly. I now understand why this man reminds me so much of him. It’s a very specific facial expression — the same one my father wore when in meaningful conversation, usually about something existential.

I want my father back every day. I see him and feel him, and I’m unsure that he could actually be gone. I have all the same questions as when I was a little girl. Yet, I am stuck. If there are answers, do I really want to know them?

I’d rather be tormented like this, unsure where he is, than to be certain he’s gone. I’d rather be lost and searching than in a place he’ll never be.

Shannon Schaefer Perri is a writer with a background in social work. She lives in Austin, Texas, with her dog, birds, cats, and husband. She is one of the cofounders of the upcoming literary magazine, the Austin Review. This essay is her first published work. Twitter: @ShannonPerri1

- Follow us on Twitter: @inthefray

- Comment on stories or like us on Facebook

- Subscribe to our free email newsletter

- Send us your writing, photography, or artwork

- Republish our Creative Commons-licensed content