Yelling over the loud rock music in the small border patrol office of the Chilean desert town, San Pedro de Atacama, the tan, jolly officer looked at my paperwork and asked in English:

“Married?”

I nodded.

He raised his eyebrows in surprise and looked around for evidence of a husband. Not finding any, he asked, confused:

“Happy?”

I shook my head.

“Por qué?”

Why? All the Spanish in the world wasn’t enough to explain why I found myself alone in the middle of a Chilean desert on the opposite side of the planet from the man with whom I’d shared more than a third of my life.

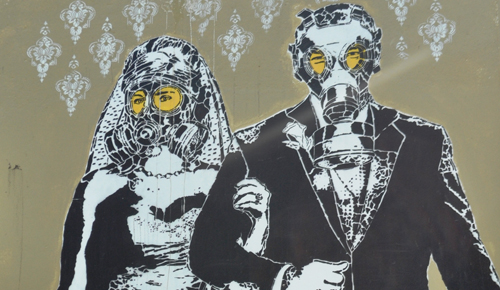

Having grown up in a divorced household, I had always been so terrified of divorce that for years I didn’t want to get married. But eventually, on one sunny afternoon, I uttered the words I do and till death, only to discover a few years later that I no longer meant them.

After a ten-year relationship, our divorce came as a complete surprise to everyone close and far, and although it was my decision to leave, that didn’t make it any easier. It felt like getting off a bus at the wrong stop. The bus pulls away and suddenly you stand there wide-eyed and alone, in the middle of nowhere, not knowing where to go, unsure whether this detour will lead to a serendipitous discovery of something new and amazing — or a sluggish struggle to get back home.

After the first few weeks of oscillating between the ecstasy of newfound freedom and pangs of loneliness and failure, I decided to make the best of my predicament and skip town. I wanted to go somewhere far away from the epicenter of my former life, leaving everything familiar in hopes of forgetting, distracting, discovering, healing, and eventually moving on.

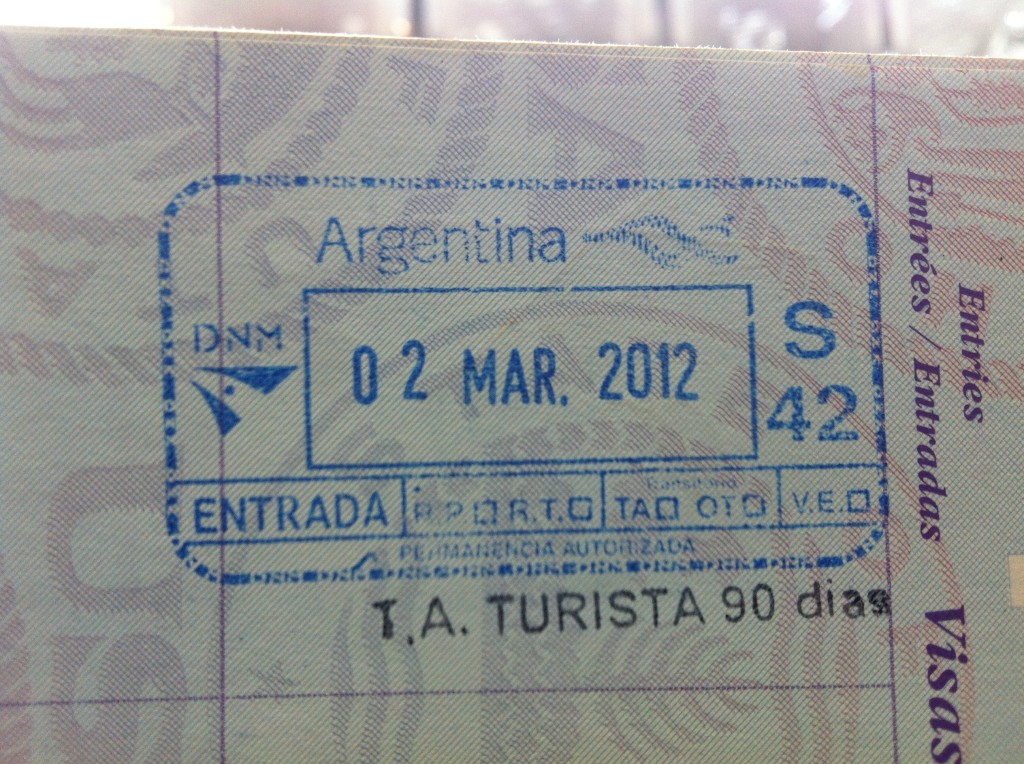

I looked at the world map and saw South America, which beckoned with the promise of untamed nature, sexy music, exotic fruits, and tropical heat. The fact that I didn’t speak Spanish or know a single person on the continent wasn’t a problem. I had been comfortable far too long. Now I needed an adventure.

Traipsing through five countries in three months, I climbed huge mountains, gasped at divine waterfalls, danced until the wee hours, and ate a lot of strange things. But the memory of my divorce was never far.

No matter where I went, I seemed to meet other young divorcés.

Hours after my plane landed in Uruguay, I met Ignacio, a thirtysomething local businessman who married his young girlfriend after she became pregnant. The marriage didn’t last long, but he didn’t regret it because of the beautiful daughter they share. He told me my situation was easier because we didn’t have any children.

Then, at an expat happy hour in Buenos Aires, I met Leo, a freckled New Yorker who needed a drink after the latest frustrating attempt to divorce his Argentinean wife. She was ignoring all his communications, thus solidifying his belief that all Argentinean women were crazy. Not surprisingly, Leo’s advice to me was to get a lawyer.

Being a crazy Argentinean woman was exactly why my other new friend — Ana, a tall and striking redhead — was forced into a divorce by her Spanish husband. Two years earlier at work, she had a breakdown that turned into a bout of depression, and he wasn’t willing to deal with it. Ana told me she would never love again, and although I’m sure that won’t be the case, I knew exactly how she felt.

Another friend I made in Buenos Aires, Pablo, told me his marriage ended after he started his business, a neighborhood pub. Or at least that’s what I understood from his long, Spanish-only monologue over two bottles of wine we shared in an old San Telmo restaurant. Having started a business with my husband, I knew more about that than I could express in my limited Spanish.

Then, in Chile, I met Raj, a Canadian entrepreneur of Indian descent, who told me about his marriage to an Indian high-caste girl, his first love, who wasn’t willing to stand up for herself — or for them — to her strong-willed parents. He said that after he left her, he was certain he had made the right decision because she never asked him to come back. Ah, I know the feeling, I thought.

In Peru, my Spanish teacher revealed that she had left her partner of fifteen years — the father of her two children — after he decided to have children with someone else. Naturally, our lessons quickly devolved into exchanging post-divorce dating stories, which left me with some unique Spanish vocabulary.

In Rio de Janeiro, my youthful, blond roommate Leticia turned out to have a twenty-year-old son, whom she’d inherited from her first husband. She has had many lovers since but never remarried. On the night I received my divorce papers, she took me to a bar and said Brazil was one of the best places on earth to get served. I couldn’t agree more.

Although these people’s circumstances were different from mine, I was starting to feel much less alone as my divorce became just one dot on a world map of broken hearts. And then, I met Hugo.

A tall and soft-spoken man with red hair, Hugo was a friend of a friend who owned a mountain lodge in a small resort town in the lake region of the Argentinean Andes. I went up there for a weekend to ruminate. I was the only guest, so while cooking dinner in the kitchen, he took out two beers and asked for my story.

As soon as I got to the “I’m getting divorced” part, he stopped, turned from the stove where he was stirring something in a pot, and said, “You too?”

He told me he was also getting divorced after also spending a decade with his wife, who was also my age. It was starting to sound familiar. Then, he sat down opposite from me, took a sip of beer, and told me his wife had left him because he’d been addicted to drugs.

I was shocked. Not only because of the courage it took to admit that to a complete stranger, but also because it was the exact same reason I’d left my husband.

We both fell quiet, as the boiling water gurgled on the stove. This is what it must feel like when two soldiers from the opposite sides of the trenches meet after the war, I thought.

Slowly, Hugo began telling me the story of his transgressions: how his wife found out, how he kept promising he’d change, how he kept lying, and how finally she stopped believing him and left. I was listening to the story of my life.

He told me she was still angry with him. Check, I thought. He told me that she doesn’t trust him even though he no longer lies. Check and check.

It was the lying that was the worst, I explained.

“I know,” he said. “I wasn’t just lying to others but also to myself. I thought I could stop anytime I wanted to, but instead I kept going.”

Why couldn’t I have heard this from my ex-husband? God knows we tried to talk it out, but anger, shame, or pride would always cloud our minds. Instead, here I was having one of the most intimate, gratifying conversations I’d ever had, with someone I’d just met.

We moved to the living room, where Hugo, a father of two young children, told me about the guilt he was now feeling for having lost his family because of a substance. His words reminded me of my ex-husband’s post-divorce confession, “How am I supposed to live with the guilt?” I could see the agony in Hugo’s blue eyes, and it made me empathize with my ex-husband.

It was getting late and we were both exhausted by the emotional conversation. After Hugo went to bed, I sat on the terrace gazing up at the unfamiliar South American constellations, bright and clear in the cold mountain air. How was it that despite being half a world away from my former life partner, I felt I understood him better than ever before?

It was a therapeutic weekend for both Hugo and me. We took his kids sailing around the mountain lake, hiked through pine forests, and went to a party where he introduced me to other business owners in town. It was more than I had expected from my short getaway. And yet, when I was leaving, it was Hugo who was full of gratitude: “Thank you, it has been a very long time since I had such a nice, peaceful weekend.”

Even though I’ve now left South America, its magic is still with me. I keep in touch with Hugo and other divorced friends I made on that continent, and I know that no matter where we are, eventually we’re all going to be all right.

Pseudonyms have been used to protect the identities of the individuals mentioned in this story.

- Follow us on Twitter: @inthefray

- Comment on stories or like us on Facebook

- Subscribe to our free email newsletter

- Send us your writing, photography, or artwork

- Republish our Creative Commons-licensed content