Standing on the edge of the Red Sea 60,000 years ago, the first people looked across the water, saw mountains rising above the horizon, and decided to go there. No one knows how they crossed the water, but they did. Somehow, this small band of as few as 150 individuals made their way from Africa to Arabia — from what is now the tiny country of Djibouti on one side, to the troubled nation of Yemen on the other. After that, they kept going. They followed the shorelines. They went inland. They scaled mountains and crossed plains. They spread out into the world until they filled every corner of it.

They, of course, were us.

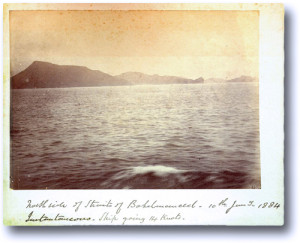

Bab al-Mandeb is thought to be the place they crossed. It is the “Gate of Tears,” where the Red Sea narrows and powerful ocean currents have sunk countless ships over the ages. But back when those first people crossed, the oceans would have been 400 feet lower, so instead of seventeen miles of water there would have been just seven, with islands along the way. Today the islands are submerged and the ends of the strait reach out to each other like a continental version of Michelangelo’s Creation of Adam.

When I first read about this, I found the place on a map. The language those people spoke, the clothes they wore, the thoughts they had — those are all gone forever. But the place is still there, and I knew I wanted to go there. I wanted to be where it all began.

The problem was I couldn’t think of any good excuse to go to Djibouti. It’s a hot, dry, poor country in the middle of nowhere whose only export is people on their way out. Almost all the information I could find told how to get from Djibouti to someplace else.

Then one day a few years ago, I heard about the Bridge of the Horns, a massive project that aimed to span the Red Sea, linking Africa and Arabia in a way they had never been before. It was announced with great ceremony at a 2008 press conference in Djibouti, and those present were taken aback by the audacity of the scheme. The bridge would be eighteen miles long with 100,000 cars crossing it daily on a six-lane highway, as well as 50,000 rail passengers and four light-rail lines. There would be pipelines for water and oil. At each end, a new city would be constructed — a “City of Light” — to be populated by 2.5 million people on the Djiboutian side, with 4.5 million on the Yemeni side.

It was a bold, beautiful vision. It would create millions of jobs. It would bring commerce, peace, and prosperity. It would funnel a massive amount of traffic safely over the troubled waters below.

It was also absurd. Eco-cities in Djibouti? Thirty-six million cars a year? Then again, I had been to Dubai, just across the Arabian Peninsula, where in thirty years they’d turned a tiny pearl-diving village into a global financial hub and home to the world’s tallest building. I had seen what could emerge from a pile of sand: shopping malls, theme parks, man-made archipelagos.

So who knew? Bab al-Mandeb was already a place I wanted to go. It was a hole in my imagination I needed to fill. For several years, I pitched the story before I finally managed to get an assignment to write about the Bridge of the Horns. The money would only cover part of the costs. But it would be just enough to get me there.

It was 3 a.m. when my plane landed in Djibouti City, and I had no idea where I was going to stay. There was little travelers’ information online, and even my Lonely Planet devoted just twelve pages to the country, which began: “Never heard of Djibouti? Don’t feel bad.”

At immigration, the official stared at my passport and asked several times, “Tourism?” as if he couldn’t believe it. I nodded and said, “Yes, tourism,” which was true enough. He shrugged, stamped my passport, and waved me through.

Outside there was one taxi in the parking lot. The driver asked me where I wanted to go and I blurted out “Sheraton.” He nodded knowingly. We pulled out of the parking lot and sped into city. As we drove past the beach, I saw hundreds of people lying on the sand, their silhouettes visible in the pale blue moonlight. I made a mental note: if all else fails, sleep on the beach.

At the Sheraton, I walked to the front desk, set down my bag, and asked how much a room was. The man told me it would be close to $200.

“That’s a little out of my budget,” I said. “Do you mind if I wait here till it’s light?”

“No problem,” he said, and pointed to the couches in the lobby.

When I woke several hours later, the sun had risen and the room was full of German soldiers greeting each other with “Morgen” and “Morgen.” They ignored me as they watched TV and drank their coffee before heading out to report for duty.

By the time they left, the city seemed to be rousing itself, so I shouldered my pack, walked out into the heat, and entered what had once been dubbed the “Hell of Africa.”

For a place where there isn’t much to do, Djibouti City is insanely expensive. This is partly because the country is a rocky desert, and everything has to be imported. As one scholar noted, the country has “virtually no arable land, no permanent fresh water source, no significant mineral resources, very little vegetation, an average daily temperature of 34°C [93°F], and severe, persistent drought.” Even the electricity was rumored to come from two discarded ship engines outside town.

Djibouti has been this way from the beginning. The site of the city was chosen by the French in the 1880s for its location, and to this day its location is its main asset. Sitting on one of the world’s most important shipping channels, through which much of the world’s oil flows, it is an island of relative stability surrounded by turmoil.

In fact, its geography has been called Djibouti’s “unusual resource curse,” because almost every country in the world wants a military base there. As a result, the country has become a kind of geopolitical slumlord, charging exorbitant amounts to host fighting forces from across the globe, including 2,900 French troops, 1,500 Americans, 800 Germans, 50 Spanish, and 180 Japanese (who operate Japan’s first overseas military base since World War II). Every day, fighter jets and heavy aircraft roar through the sky. At the airport, you can sit in the departure lounge and watch drones taxiing across Camp Lemonnier, the U.S. military base.

All of which means there is no budget-travel scene, because most foreigners are here on an expense account. Nonetheless, my first day I did manage to find a place to couch surf for a few days, in an extra room at an Internet café. The following day, after that was settled, I headed to town to start my search.

At the very center of Djibouti City is Menelik Square, an open place in what was once the “European Quarter” of town. It’s surrounded by old colonial-Moorish buildings that look like they might have been glorious in another era. These days, many of the buildings around town are empty and their facades serve as makeshift urinals. As the heat of the day rises, the smell of baking urine wafts through the streets. The city has a rundown, forgotten look that makes it feel like something in a Graham Greene novel. Strolling the streets, I walked past Pakistani barbers, Yemeni electronics dealers, Ethiopian restaurants, French grocery stores, and Somali coffee shops. Djibouti is, as it always has been, a kind of crossroads between nothing and nowhere.

Across Menelik Square, past two defunct telephone booths, I spied a small bookstore. Surely, I thought, this was the kind of place information flowed through. Maybe there was even a book about the bridge. I went over and ducked inside. Most of the titles were in French, with a small English section. The owner was a friendly young Indian man.

“Are you from Djibouti?” I asked.

“Yes,” he said. “I was born here.”

“Do you like it?”

“Well,” he said, “all you get in Djibouti are booze, babes, and bridge.”

“Bridge?”

“Cards,” he said, and made a dealing motion with his hands.

“I thought you were talking about the bridge to Yemen,” I said. “Do you have any books about that?”

“No,” he said, “It’s two years now since I heard anything about it. They announced it, then nothing.”

“So they’re not building it?”

“I don’t know. They were supposed to finish it in six months. But this is Africa. If something is supposed to take two years, it will take twenty. You just have to add the zeros.”

I bought a paperback, thanked him, and stepped back out into the heat.

The next day, when I knew my way around a little, I decided to get serious about the bridge, first by asking people I met around town about it. One Yemeni man told me that the work had stopped, but that all the equipment was still there. An Ethiopian man said he hadn’t heard anything about it. A Somali man told me there was too much corruption for that to happen. Most of my inquiries were met with indifference, which struck me as strange: here was one of the world’s biggest projects on one of the world’s most important sites, but no one seemed to know or care much about it. In the end, I would have to go there to see for myself.

I stopped in the National Tourism Office to ask about how to get up to Bab al-Mandeb. The woman behind the desk suggested I take a taxi from Obock, the last town on the road north to Eritrea. She handed me a photocopied list of hotels there, then told me the office was closing, since it was almost 1 p.m. That’s when Djiboutians begin their three-hour, narcotic siesta, during which they chew the leaves of a psychotropic plant called khat.

Since Djibouti is an arid desert where nothing grows, the khat comes from Ethiopia, and the average family spends 40 percent of their income on it. Until around 2010, the khat arrived every day on a plane that landed at noon. Traders would race back to the city from the airport, then all the shop doors would shut tight until late afternoon, when things slowly came to life again.

Now the khat comes on overnight trucks, and you can buy it all day, but the siesta remains and the streets are eerily empty. It was during this time that I was walking along when I heard someone yell, “Hello, my friend!”

I looked to see a man waving me over. He was sitting on a piece of cardboard, under a crumbling portico, with another man. I walked over and shook his hand. He smiled. There were green bits of masticated leaf smeared across this teeth and gums. His cheek was jammed so full of it that it looked like a giant pustule ready to burst.

“Sit down, sit down,” he said. His wife brought over a piece of cardboard for me, and I sat. He started speaking in broken English. I asked where he’d learned it.

“I was working in the shipping,” he said. “I saw many places! So many places. I speak Greek! You like Djibouti? Djibouti people?”

“Yes,” I said.

“Djibouti people very good,” he went on. “Djibouti is security. Not like Yemen. Yemen there is always fighting. Arabs fighting. Libya. Yemen. Don’t go to Yemen.”

“Why?”

“Yemen is bullshit.”

“Don’t they want to build a bridge to Yemen?” I asked.

He didn’t answer, but just stared out into the street and muttered to no one in particular, “Yemen is bullshit.”

Yemen might be bullshit today, but around 60,000 years ago it wasn’t. No one is exactly sure what it was like, but there is evidence that it would have been a kind of paradise for early hunters, a place with plentiful rainfall, rivers full of fish, and large game roaming across what is now known as the Empty Quarter. It was a place where the grass may have literally been greener.

For a long time, archaeologists assumed that humans left Africa via the land bridge connecting Egypt with the Middle East — what is known as the Levant. The problem was that there was little evidence on the ground of this so-called Levantine corridor.

But in the late twentieth century a new theory arose, which held that there was another route out of Africa by way of Bab al-Mandeb: the “southern corridor,” or the “Arabian corridor.” According to this theory, people then followed the Arabian coast up and around to India, and from there out into the wider world, sailing, walking, and climbing to every corner.

This happened in a very short time, historically speaking, and no one knows exactly why. But something seemed to have changed, and many think it was something in those people. The archaeological record is confused and spotty and tells contradictory stories. But in the 1990s and early 2000s, the field of “genographics” began coming into its own, by which scientists traced the DNA mutations in populations around the globe. This way they could follow our ancient routes like so many genetic breadcrumbs.

Among the theories that emerged was one that said all modern humans are descended from a group of about 5,000 people, who survived the global winter caused by the eruption of the Sumatran supervolcano Toba 74,000 years ago. Shortly after that, these people started moving around the continent and beyond.

Specifically, it appears there was one group of 150 to 550 people who crossed the Red Sea at Bab al-Mandeb in search of something. All we know is that once they started moving, they spread out across the world very rapidly, and today nearly all non-Africans are descended from them.

It is a story that is being constantly rewritten by new discoveries. But we are sure these people had language, art, and abstract thought. They could plan ahead, navigate, and imagine what they couldn’t see. It seems there was something different about them from those who had gone before them. Others had crossed the Red Sea earlier, but these groups appear to have died out or stayed put. But this last group, once they made the crossing, never stopped.

I wanted to stand where they’d stood. I wanted to picture in my mind’s eye what they might have seen in theirs. I wanted to look across the water as if looking back in time.

On the street, a van pulled up where I was standing. The door was broken, and a tout hung out the window rattling some coins in his hand. “Héron?” he asked. I nodded and got in, and we rolled out of downtown and through the quiet, diplomatic area of Héron. At the end of the road we came to an otherworldly place called the Djibouti Kempinski Palace Resort, the country’s first five-star hotel.

I climbed out, walked across the grounds, and went through the front door. It was like passing through a wormhole into another dimension. One minute I was in a blazing hot, corrupt, miserable dump of a country. The next I could hear violins and the trickle of a waterfall, and my body was in shock from the cold. There were marble floors, ornately carved chairs, colorful stained-glass lamps.

I’d come to the Kempinski to meet a middle-aged, clean-cut man named Houssein who gave birding tours throughout the country — and who knew a lot about remote regions like Bab al-Mandeb. I found him in the Kempinski café and we drank five-dollar glasses of orange juice while we looked over a map of Djibouti. Houssein pointed to the area around Bab al-Mandeb.

“This area is closed,” he said, “because there are some problems with Eritrea.”

“Problems?” I asked.

“Yes,” he said. “Eritrea invaded, and now the situation is under some kind of mediation. But I think they closed the road after Obock.”

I looked at the map. Obock was the old town where the French first established their outpost in 1862, before the colonists moved across the bay to Djibouti City. Today it’s the last town of any size on the road to Bab al-Mandeb.

“That is where they are building the bridge, right?” I asked.

“Yes. Actually they announced the bridge here, at this hotel,” he said.

“And what did people think of it?”

Houssein shrugged. “Well, if you are not connected with reality, you can believe it. But it is very difficult. It is twenty-eight kilometers. The maritime currents are terrible. Sometimes even these supertankers are struggling to get through. I don’t know. These people are crazy.”

“There’s no infrastructure there at all?”

“No! These are fishing villages. The people don’t even know how to build houses. They don’t even need houses, because it’s warm all the time and they sleep outside. And there was supposed to be a city with one million people on one side, and a million people on the other side? I think it was somebody doing drugs and saying, ‘Oh, this is a good idea.’”

Back in town, at Menelik Square, I ducked into Djibouti’s Planet Hollywood knockoff. The walls were plastered with black-and-white photos — Madonna, Mel Gibson, John Wayne, etc. The waitresses were sassy and looked like they might moonlight in an older profession as well. I took a seat and spread out my notes on the table in front of me.

This news about the invasion was unnerving. When I’d tried to find out what was going on with the bridge before leaving the U.S., no one had mentioned any invasion. Before I’d left, I’d called the Djiboutian embassy in Washington, and they had assured me that it was still on track, that construction had begun, or would begin soon, and that they were just waiting for some funding that hadn’t quite materialized.

Then I had talked to Dean Kershaw, one of the engineers involved, who told me the project was definitely off, and that the original cost of $200 billion ($50 billion of which they had raised from Dubai) would more likely be $400 billion.

So I had emailed Tariq Ayyad, CEO of Noor City Development Corporation, which had been formed to spearhead the project, and he wrote back to say the bridge was still going forward but was “on hold untill political climet [sic] been addressed.”

Clearly there were mixed messages, which I sort of expected. But I hadn’t expected to be heading to the front lines of what the New York Times called a “David-versus-David battle,” between “two of Africa’s tiniest nations squaring off over a few piles of uninhabited sand.”

At the table next to me, three Somali businessmen sat talking among themselves. After a while, one of them turned and started chatting with me. He slid into my booth and asked what I was doing. I was looking at my map.

“I want to go to Bab al-Mandeb,” I said, “to see the bridge they are building.”

“Ah, the bridge,” he said, and waved his hand. “I think it was just a dream of our president. But also, that was the reason  Eritrea invaded. They said, if you build this, we will take it.”

Eritrea invaded. They said, if you build this, we will take it.”

“That’s why Eritrea invaded?”

“Yes, of course.”

I looked at the map.

“So they can’t build it?”

“No,” he said. “Never.”

Part of me had known all along that the bridge was a fiasco. But I loved the idea of it, the irony of the first crossing overlaid by a second, as if humanity had come full circle. Once I got to Djibouti, I thought I would be inspired to muse about bridges, but now every bridge metaphor seemed to end in a cliché. Honestly, I had no idea what I expected to find up at Bab al-Mandeb. Some deserted equipment? A sign next to an empty lot that said “Eco-city”? Nothing at all?

Now I was starting to wonder if I would even get there. After all, that was the real reason I was in Djibouti: because of that older crossing, the one where we took our first steps into the wide world and became the species we are — restless, forward-moving, curious, able to see not only what is, but what can be.

How those people got across the Bab al-Mandeb is a question that will likely never be answered. The real question for me was why? It’s possible they ran out of food, or were escaping from hyenas. But then they kept going over every horizon. They built boats and sailed across oceans with no land in sight. At the Max Planck Institute, evolutionary geneticist Svante Pääbo told the New Yorker he is comparing human DNA with those from Neanderthals and others to see if he can find out whether “some freak mutation made the human insanity and exploration thing possible.”

Pääbo’s notion that our restlessness is innate speaks to me on many levels: as a traveler, a writer, as someone who gets bored with any routine that lasts longer than a week. Growing up, the hills around my hometown always felt like prison walls. After I escaped, I spent much of my young adulthood exploring unknown corners of the world, trying to fill what felt like a bottomless need to see and know things. The movement was intoxicating, addictive, exhausting, and fulfilling.

Life goes on, however, and if you want other things out of it, you have to meet the people you love halfway. But even after my wife and I bought a house and had children, the restlessness remained. I have found as many outlets for it as I can, and cultivated my inner life, but deep down I still feel torn between the devotion to the family I love and this other need. I struggle to find a midpoint between stasis and motion — between “citizen and nomad,” as novelist and travel writer Bruce Chatwin put it.

Outside Planet Hollywood, I looked at my watch. The shops were closed. The heat was crushing. I tried to think of something to do. My guidebook listed two things to see in the city — a mosque and the market — and I’d seen them both. The stasis of the city was starting to wear me down: it was time to get back in motion.

I went to my place and packed up my things. In the morning I walked across town to a dusty lot littered with discarded car engines, where I found the “bus” (a Toyota Land Cruiser) going to Obock. It was a little after 1 p.m. when we pulled out of town.

The road wound up and down through the mountains. It was hot, rocky, and barren. At Lake Assal, 500 feet below sea level, the temperature must have been around 115°F. It felt like driving across another planet. The only thing that seemed to grow out of the ground were rocks and the occasional scrubby tree.

Three of us were jammed in the front seat next to the driver, and twenty more in back. I had to move my leg every time the driver shifted. Next to me was a young guy named Ali who said he was from Ethiopia, but who I later learned had escaped Eritrea and was waiting for his papers.

It felt so good to be out there, traveling though a new landscape, slaking my thirst for motion — a feeling Chatwin knew well. “Why do I become restless after a month in a single place,” he wrote, “and unbearable after two?” He spent much of his life trying to explain this need, and when he died he left fragments of a manuscript called The Nomadic Alternative, in which he tried to prove that “evolution intended us to be travelers,” and that “travel does not merely broaden the mind. It makes the mind.”

Writer and traveler Michael Mewshaw voiced a similar sentiment, saying that for him travel “isn’t just a way to escape, as Graham Greene put it, or a way to gather material or battle against boredom.… It’s my method, à la Arthur Rimbaud, of systematically deranging my senses, opening myself up to the new and unexpected.”

Rimbaud — the poet and patron saint of modernity, and one of the giants of French letters — abruptly left his literary life behind in his early twenties, eventually settling in Djibouti, before moving on to Ethiopia. The first place Rimbaud landed was a tiny, sweltering village on the Red Sea called Obock, where he, in a real sense, became a new person. I’d always read Rimbaud’s story with a kind of longing, because of its sense of creation, discovery, and rebirth.

That, more than anything, was what I loved most about new places, new languages, and new cultures. It was seeing the world of possibilities expand before my eyes and letting them become part of me. It was this sense that new places, people, and ideas could make you into a new person.

It was nearly dark when we pulled into Obock, which was Ali’s stop too. After we’d piled out of the car with our bags, I asked Ali if he knew where a hotel was. He turned to ask a woman walking by, then turned back to me with a troubled look.

“No hotel,” he said.

“What about the Village Mer Rouge?” I asked.

“Closed.” We stood in silence until he said, “Wait here.”

A few minutes later, he came back with a friend who spoke better English. They took me down a hill to a small house where a man who owned a shipping company rented out rooms: thirty dollars for a cot, a locked door, and an air conditioner.

It was a low, one-story building, and the only thing in the room besides the cot was a plastic chair. There were heavy wooden shutters on the window, but it seemed safe enough, so I set my bag inside, locked the door, and wandered out to look for something to eat. I found a small shop where I bought a baguette and a packet of cheese, then walked down to the water where I sat on the sea wall.

The moon was out. The beach in front of me was littered with trash. Small crabs skittered over the refuse, in and out of holes, while dogs roamed about, looking for scraps.

Behind me sat the small, ruined house where Rimbaud once lived. The roof was caved in, and it was full of building supplies. But it was still there. I wondered what the poet would have seen as he looked out his window. Even in the moonlight, it was hard to tell where the water ended and the sky began, let alone imagine what lay beyond it.

When I’d read about those first people crossing the same waters 60,000 years ago, I’d felt a sharp sense of recognition, like we must be from the same species, one drawn to the horizon, one whose restlessness was something deep and old. It’d made me feel like that’s who we are.

The next morning, I walked through town trying to find a taxi, or a bus, or some other way to get to Bab al-Mandeb. But no sooner had I started making inquiries than a battered pickup pulled up beside me. The driver was a wiry old man dressed in military fatigues. There were two people in the backseat.

The driver motioned wordlessly for me to get in. I stood there for a minute.

“Police,” he said. “Come.”

“Why?” I asked.

He didn’t answer, but motioned again and looked ahead.

There was nowhere to run, even if I tried. So I got in and we drove to the other side of town without speaking. When we arrived at the police station, I was told to sit at a table in the yard out front. Several officers sat around me. One in a white T-shirt seemed to be in charge. He lit a cigarette.

“Tell me why are you here,” he said.

“Tourism,” I answered.

“And where did you come from?”

“Djibouti.”

“You have a car?”

“No,” I said. “I came in the Land Cruiser.”

“The white one?”

“Yes.”

“Why are you here?”

“Tourism.”

“Tourism?”

“I want to go see Bab al-Mandeb.”

“Ah,” he said with a scoff, “that is not possible. The road is closed.”

“Closed?”

“Closed. No tourists. No foreigners.”

“Because of the war?”

“Yes,” he said. “You have a visa?”

“Yes.”

“Show me.”

I handed him my passport. He leafed through it lazily.

“What is your work?”

“Teacher,” I said. As they talked among themselves, I was sure I heard the word journalist. After some discussion, the man copied down my passport number and handed it back to me.

“Okay,” he said. “Thank you.”

The sun was high by the time I got back to town. Military trucks rolled by on their way to the northern front. Bab al-Mandeb wasn’t far — just forty miles away. Yet it might as well have been on the other side of the moon.

The thought of stopping, of giving up, was unthinkable. I’d come so far. I was so close. Outside Obock, I’d seen a lighthouse on a point called Ras Bir. It was high and isolated, and I thought if I climbed up it I might get a glimpse of the Gate of Tears.

I started asking around for a ride. One guy wanted sixty dollars, which I didn’t have. Another asked for two hundred dollars. After trying a few more people, I walked to the north side of town. The lighthouse was a tiny upright sliver on the horizon. The distance was supposed to be nine kilometers, about five miles. I’d gone farther than that on foot before. So I just started walking.

The sun was relentless. The only sounds along the way were the wind, my breath, and the crunch of rocks under my feet. Far off the road I saw a lone goat herder, but otherwise not a soul. To my left, I passed some caves, and I wondered if someone might be in one. Down by the sea was an abandoned resort, its round huts slowly falling apart. I felt utterly alone as I moved across the plain, with no idea what I would find when I arrived.

I walked and walked, but the lighthouse never seemed to get closer. I had a lot of time to think, and I wondered if this could have been what it was like for those first people who lived along this shore: fishing, hunting, dreaming. It’s possible they had been in this very place, and that my footsteps fell in theirs, as they traveled up and down the coast looking for a way out into the world.

After an hour, I ran into some wild camels and gazelles and wondered idly if there were also hyenas. But by then, the city of Obock had grown small and there was nothing to do but go on. Slowly, the lighthouse drew nearer. It felt like I was in a science-fiction novel trekking toward a remote outpost of civilization.

When I finally arrived, I followed the wall around to the gate, which was open. I walked inside. Several young soldiers stopped what they were doing and stared at me in mild shock. One stepped forward and introduced himself. His name was Hassan.

“You want to go up?” he asked.

“Yes,” I said.

He spoke to his boss, then came back and motioned for me to follow him. Together, we wound upward through the dark, along concrete stairs inside the tower, until we came to a small balcony that encircled the beacon.

I followed Hassan though a doorway. Outside, high above the sand, the world opened up before us. He leaned over the railing and looked at the water below.

“It’s beautiful, isn’t it?” he said.

The sea was deep blue. The sand was bright gold.

“Yes,” I said. “It’s very beautiful.”

He pointed east across the water. “Yemen is there.”

He turned and pointed south. “Djibouti is there.”

He pointed north. “Eritrea is there.”

“And Bab al-Mandeb?” I asked.

“… is there,” he said, and pointed far off, to a place where the sea and land faded into the haze.

I looked to where he was pointing and squinted in the sun. I was sure I could almost see it.

Originally published by Nowhere magazine.

- Follow us on Twitter: @inthefray

- Comment on stories or like us on Facebook

- Subscribe to our free email newsletter

- Send us your writing, photography, or artwork

- Republish our Creative Commons-licensed content