We knew only one thing: We needed to pack sleeping bags and rubber gloves. Jenn, my friend and farm coworker, and I were gearing up for our trip to Humboldt County.

It was the old “friend of a friend who knows a guy” scenario. Yes, that’s how we committed to working on a medical marijuana farm. We didn’t know specifically where we were going, what the work entailed, who we were going to be working for, where we would stay, or even how long we would be there. But somehow, from our comfortable couches in Los Angeles, the complete omission of specifics only heightened our anticipation of the adventure. All Jenn and I needed to hear was “$20 per hour cash” and “marijuana farm.” We were in.

We had been instructed by the Bossman to wait in a small town about 40 minutes away from our destination. He would meet us nearby and then escort us to the farm because there was “no way” we’d find it on our own. He was right.

During our hour or so of waiting for him, we were entertained by the sight of packs of dirty hippies. I say the term “dirty hippies” lovingly, as I spent the first seven years of my life in a hippie commune. But apparently in order to qualify as a dirty hippie in Humboldt, you must A) have a dog with a hemp rope tied around its neck, B) be barefoot, C) smell like BO, turmeric, and flightiness, D) ask for money, and E) style your hair with nail clippers and mud. A tension exists in Humboldt County’s new social strata, as the locals are repulsed by this ganja-reeking crowd but attracted by the money they spend.

Finally, we got the call from the Bossman. It was time to go to the farm.

We were instructed to meet him by the side of the highway, which seemed rather gangsta. We were excited and nervous, but mostly excited.

And then we saw him waiting for us, our Bossman — an energetic, bandana-wearing Southern boy with a slight Eau de Hippie.

How it all began

I’ve long had a fascination with marijuana. When I’m numb from hearing about health care, unemployment, foreclosures, and H1N1, I turn to the debate over legalizing medicinal marijuana for stimulation. The agri-counter-culture that is budding in California is at the very least interesting.

For those in an ethical struggle over the value of legalizing pot for medicinal purposes, try a more pragmatic angle: the United States would experience staggering economic benefits from its legalization. According to a National Public Radio report, each Southern California pharmacy contributes hundreds of thousands of dollars per year in state tax revenue. Then there’s the geopolitical bonus: Stateside-grown marijuana directly threatens the dominance of Mexican drug cartels.

In fact, according to CBS, “The shifting economics of the marijuana trade have broad implications for Mexico’s war against the drug cartels, suggesting that market forces, as much as law enforcement, can extract a heavy price from criminal organizations that have used the spectacular profits generated by pot sales to fuel the violence and corruption that plague the Mexican state.” Yeah, duh. Of course “market forces” can take a bite outta crime. Think Al Capone and the repeal of Prohibition.

And then there’s the social justice angle. Users — perhaps you and I — will no longer have to risk buying weed from the sketchy kid down the block. Instead, we can take our cash and our self-respect and purchase our sack from the local, taxed, state-regulated pharmacy. I’m thinking you’d rather go to a pharmacy instead of waiting for “Tyler” to text you back to let you know the “Red Head” has arrived. Do we really think that by keeping marijuana illegal it’s going to go away and that bunnies and unicorns will run free?

I was once in a grow house up in Sonoma County, but it was literally that — a regular suburban house with its bedrooms converted into marijuana grow rooms. Each room had 30 6-foot-tall plants and an exceptional amount of lighting and fans. It was very impressive, very well contained, and definitely NOT “green” (as in carbon-neutral).

Because medicinal marijuana in California is an emerging industry, the laws are murky. According to the Drug Enforcement Administration’s website, “In California there is no state regulation or standard of the cultivation and/or distribution of medical marijuana. California leaves the establishment of any guidelines to local jurisdictions, which can widely vary.”

The laws are different in every county and every city. In Los Angeles County, each card-holding patient or “caregiver” (someone who grows marijuana for patients) can grow fewer than 10 plants. In Sonoma County, the maximum jumps to 30 plants. And in Humboldt County, a caregiver can grow up to 99 plants! Seems like encouragement to move from houseplants to farming. How much bud a caregiver or patient can carry at any one time also greatly varies per county. So as long as you’re following the specifications of your city and county for growing, you have nothing to worry about as far as the state’s law is concerned.

The thing you do have to worry about is getting robbed. It’s not the law that is the danger, but rather gun-slinging criminals. People associate growing marijuana with mountains of cash, which is a fairly accurate assumption. Grow houses are risky, as the smell alone, wafting from the house, is enough to give someone a clue. The blacked-out windows and the air-conditioning turned on full blast in January are additional clues. So if you’re considering starting your own grow house, do yourself a solid and get an off-site safe.

Anypuffpuff, speaking on the phone about the details of our trip wasn’t smart. Marijuana, medicinal or not, is still illegal federally, so Jenn and I could only assume the situation in Humboldt would be similar to the one I witnessed in Sonoma.

We had heard through the grapevine — from the friend of a friend who knew the guy, our soon-to-be Bossman — that our job description on the farm was to be “trimmers.” We were unsure of what being a trimmer entailed, but it sounded like something you might learn in home ec class.

In addition to our sleeping bags and rubber gloves, we also packed running shoes for daily jogs by the river; yoga mats for morning asanas; DVDs for movie nights in the cabin; bikinis for the possible Jacuzzi on premises; multiple purses, because really, you just never know; tweezers, just ’cause I’m in Humboldt doesn’t mean my brows have to go to hell; our computers for intermittent Internet distractions; and a plethora of different outfits. We were starting to think of this as our “Humboldt Vacation.” The marijuana gods were laughing.

But that’s the lifestyle we were expecting to live for two weeks while communing with nature and trimming some ganja. This is what actually happened …

The road to nowhere

After following our Bossman for 30 minutes up a winding, deserted mountain road, I not only started seeing our town outings evaporate, but I also began to see our faces on milk cartons.

We pulled up to the bottom of a very steep dirt road, and Bossman jumped out of his car.

“Okay ladies, some cars can make this road, and some cars can’t.” ’Nuff said. I’d like to be in a car that can, por favor.

It should be noted here that I have a Prius, which I now know is perhaps the world’s all-time worst off-roading car. It barely clears speed bumps, and Priuses are to steep hills what I am to corporate ladders — you’ll never see it climbing one.

Bossman continued. “So you should start way down there, at the bottom of the paved road [about 50 yards], and gun it. Then once you hit the dirt road, just keep pushing on that gas, and hopefully you’ll make it to the top.”

“Um, can I just park it down here?”

“No, ’cause during trimming season there’s lots of weirdos up here who will strip your car.” Flashing red light in brain…

I was in over my head. Why did I feel the need to add “marijuana trimmer” to my already ridiculous resume? But at this point, I was in too deep. We had just driven 11 hours from Los Angeles, and I was now depending on this money. The market showed its ugly face again. No turning back.

I told myself, “Okay, I’m cool. I’m cool. No worries. I can do this,” as I tried to ignore the image of my mom’s face when I’d tell her that I totaled my car by driving it up a dirt road to trim weed. I drove to the bottom of the hill, and at the last minute I yelled out the window, “Oh, what do I do when I get to the top? Go straight?”

“Oh no! You’ll go off the side of the mountain if you go straight! You gotta cut hard right.”

Good to know.

Jenn turned to me and, in the calmest manner possible, said, “How you feelin’?”

“Like I might barf and have diarrhea at the same time.”

You know those friends who are really good influences on you? The ones who really put your issues in check? That’s what Jenn is for me. I have a tendency to be neurotic and high-strung, but Jenn is calm … really calm. But at this moment, I needed Valium.

So I gunned it. We barreled up the hill and I cut hard right, and then the Prius coughed and pooped her pants and stopped. I floored the gas pedal, but the wheels just spun and whined, and we went no further. Bossman ran up and told me to back down the hill (oh, piece of cake!) and that he would go get his truck and they would tow us up.

My level of anxiety shot through the roof, and my shirt was now covered in sweat. But I was trying so hard to be cool. At this point, I began to feel sentenced.

A few minutes later, he sped down the hill in a beat-up truck with Bossman No. 2. They jumped out and started tying a rope (which I could only imagine was made of hemp) to my bumper.

Jenn crouched down with them, coolly inspecting the situation and knot-tying, while I stood a few feet away with pee trickling down my leg. Then Bossman dropped this load: “So, we had a little land dispute and lost the cabin. But there’s space for you ladies to sleep outside.”

My brain immediately jumped to the weather forecast (watching the weather is part of my genetics) and the fact that it was going to drop to the 30s at night while we’d be there. A) I might’ve grown up in a commune, but I do NOT enjoy sleeping outside. And B) I live in L.A. and I get cold if it’s below 70 degrees. I was speechless.

Jenn, Queen of Calm, said, “Huh. Well, we didn’t bring a tent.”

Bossman No. 1 replied, “Oh, that’s okay. You can share with the guys.”

Suddenly, we were not going to have movie nights, town outings, and Jacuzzi Sauvignon Blanc-sipping; we were going to be sleeping outside in 30-degree temperatures with “the guys.” I imagined these guys were like the dirty, barefoot, grime-caked, BO-stinking hippies we’d seen in town. In my head, Mom’s face was replaced by my boyfriend’s, shoving my belongings into a box and dumping them on the sidewalk.

“Well, that about does it,” said Bossman No. 2 as he secured the rope. “I just hope it doesn’t rip off your bumper.”

Well, gosh, me too. I didn’t think Toyota Financial would recognize “bumper ripped off on marijuana trim adventure” under my warranty.

But I stuffed down all my good sense, and with paranoia burbling to the surface of my brain, I said, “Okay, let’s do this.”

And so we did it — we towed my citified car up a dirt roller coaster using a hemp rope. Miraculously, my bumper remained secure and I kept my lunch down.

Down on the farm

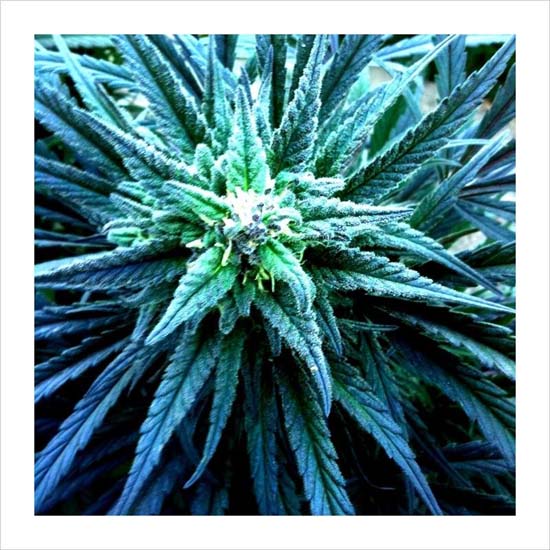

The farm really was something beautiful to behold. Nestled amongst the redwoods, the land was pristine. The only man-made items on the property were a small trailer where Bossman No. 1 and his girlfriend slept (and cooked most of our food), a large tent for trimming the marijuana, two small sheds where the marijuana dries, and THE GARDEN! This Eden boasted 45 marijuana plants ranging in size from 2-foot-tall babies to bushes well over 6 feet tall and 4 feet wide. These were some impressive plants.

We were then introduced to our workspace — the tent — and there was no getting prepared for the sight. Not scary or grotesque or hilarious, just reeeaally strange. Seated around a long table were 10 latex-gloved, heavy-metal-listening dudes — “the guys.” The air was thick with pot smoke, pot pollen, and dust from the dirt floor. The table was piled high with marijuana branches to be trimmed, and there were several large chafing dishes filled with the completed product — trimmed buds. Beautiful, perfect, and pounds and pounds of them. But the most peculiar thing about the tent was the flat-screen TV at the end of the table.

Here was a place where no one got cell reception, where we only had a Port-O-Potty, where there was no refrigeration or even ice, and where we had to sleep outside, yet we had DirecTV and a flat screen.

Metallica blared on the speakers and a baseball game filled the screen. Jenn and I were suddenly very aware that we were two women from Los Angeles in a male environment that chose TV over refrigerating meat. When we were given the option to go work in the garden by ourselves or stay in the tent to trim, in one voice we opted to work in the garden.

That first day in the garden, we couldn’t stop laughing. It wasn’t the pot — it was either laugh or cry. We kept asking ourselves what had possessed us to put our lives on hold and drive 11 hours to do manual labor with a bunch of dudes and then sleep on the ground? What were we thinking? So we just kept laughing. And pulling leaves off marijuana plants.

That was our job in the garden — pulling the leaves off the mature plants that were ready to be harvested. Doesn’t that just sound like a sweet little painless chore? That’s what we initially thought too. We had grand visions of finishing the entire garden in two days. And then we began our first plant.

First of all, we had to wear latex gloves because the resin from the plants is so thick and so sticky, in a matter of minutes you are covered in the gummy tar, which is impossible to get off. Later we learned an interesting fact: The resin can be removed from the gloves and smoked as hashish. At that moment, though, this information was not a bonus.

Anyhigh, we had to wear latex gloves, long-sleeved shirts, and long pants to avoid becoming resin babies. What we thought might take a few minutes of leaf-pulling per plant actually took over an hour per plant. There were zillions of leaves, and we had to pull delicately so as not to rip off the bud. We were immediately daunted, and as the sun bore down, we had a notion of what it must be like to be a migrant field worker.

Once the sun dropped, we joined the guys to work in the trim tent. The dust from the floor mixed with the pot smoke (yes, the trimmers smoke pot the entire time they trim — but as anyone who’s worked in a coffee shop knows, the last thing you want is a cup of joe) mixed with the airborne debris from 12 people trimming plant matter causes a sinus horror show. I blew my nose, and actual pieces of bud flew out. Listen, potheads, this is not okay. The tent was a constant cacophony of sneezing, wheezing, nose-blowing, hacking, and spitting. It was there we learned the term “the Humboldt hack.”

Trimming the buds into perfect little sellable nuggets was more mind-numbing than the garden plants’ deleafing, thus the flat screen. It also caused our hands and back muscles to cramp.

My multitasking, iPhone app-fiddling, Twittering, emailing, blogging, texting brain started to short circuit. I began to have a panic attack reserved expressly for middle class white people. How in the world was I going to do this for over a week, 12 hours a day? All the while sharing a Port-O-Potty with 10 dudes? I was not only dirty and disgusting (already!) I was bored. Picking and trimming leaves all day and night? Really? The social injustice was primarily body odor, and it seemed hardly worth the financial reward.

This was the temper tantrum my brain threw for the next two days. Bossman must have sensed my panic, because he got everyone a hotel room to share. And by hotel room, I mean a $25-a-night cell with a goat in the yard, 45 minutes away, in which we crammed as many bodies as possible. But hey, it had hot water and a roof, so I was grateful. I felt as though I were on Survivor, only without a million-dollar grand prize for surviving.

Meditations on pot

I’m not sure what got me through those first couple of days. It was probably Jenn’s constant calmness. And the fact that I needed to make this money or else I wasn’t going to be able to pay rent. It was also the knowledge somewhere deep, deep down in my gut that I needed this experience. I needed to be ripped away from my electronics, my comforts, my routine, and my false sense of control.

On the evening of day two, I had this epiphany: The universe sentenced my ass to a marijuana farm, and I had to do my time. I had to chill out, relax, and let go. If I counted the seconds, they would only get longer. I had to commit and be in the moment here more than in any of my previous meditations.

On day three, I embraced my epiphany and the work and living conditions. It started to feel less like prison and more like a spiritual retreat. I was becoming unplugged from my own expectations. That’s when I began to be fully aware of the unique experience I was having.

I started to ask the guys questions. I was amazed to find that what I once thought to be a motley crew of potheads and metalheads was in fact a group of interesting human beings. One had been a monk for 17 years in Laos. There was a chef, a firefighter, an actor, a screenwriter, a musician, a sports TV project manager, and a dad. We all had a desire to fall off the grid, if even for a brief period, and to experience some of the last days of the Wild West. And to make some fast money…

This truly was the Wild West. Our bossmen were in the throes of a major land dispute over another piece of property on which they had 350 mature marijuana plants. A mature plant can yield anywhere from half a pound to 2.5 pounds of dried bud. A pound of dried bud can sell anywhere from $2,000 to $4,000. So we’re talking about a lot of money.

The daily news told stories of local robberies and even violence. We would hear gunshots in the distance. Target practice on squirrels? Possibly. More land disputes and more robberies? Very likely. Small planes would fly over our heads as we worked in the garden. Private joyriding? Perhaps. Scoping outdoor gardens? Maybe. This is big business, and it is largely unregulated.

We often mused about how once marijuana is legal on a federal level, it will be so regulated that working on a pot farm will no longer be a retreat of sorts for those of us who are wandering and could use $20-per-hour cash. We could eat, drink, and pretty much work when we wanted. We just kept track of our hours, on scraps of paper, through a perma-haze. But once it’s universally legal and regulated, there will be masses of real migrant workers who, being paid $8 an hour, will be required to produce a certain amount of pounds per hour. There will be no DirecTV, no free Coors Light, no joint being passed around the trim table, no constant chatter, no getting to know a monk from Laos, a chef, or a musician.

But this is how it’s done now. This moment of time presents a brief opportunity for an opportunistic few to make a considerable amount of money. Cash. And let’s be clear: This Wild West scene has been created by the law.

The ambiguity of the law is tough to navigate. Proposition 215, the Compassionate Use Act, under which California voters approved the use of medicinal marijuana, is completely silent about transportation, distribution, and sales of marijuana. In 2004, SB 420 was passed, but it only focused on cultivation and possession.

Contradicting the very keystone of this debate is that while pharmaceutical prescription drugs are not taxed in California, medicinal marijuana is taxed. So medicinal marijuana is being treated more like alcohol and cigarettes under state law. This is just more evidence of the hazy laws and California’s own indecision of how it wants to treat marijuana. Like the citizens of Humboldt, the state likes the money it brings in but is having trouble with the stink.

The debate over pharmacies is likewise thick and convoluted. The laws themselves conflict and clarify little. In similar murky waters, the pharmacies and the patients who buy the bud are taxed, but the growers — the caregivers — are not taxed. Typically, a caregiver will sell his bud to a pharmacy (also called a “dispensary” or “collective” under state law) that will then sell it to the patients.

According to the California Attorney General’s elusive guidelines —

California law does not define collectives, but the dictionary defines them as “a business, farm, etc., jointly owned and operated by the members of a group.” (Random House Unabridged Dictionary; Random House, Inc. © 2006.) Applying this definition, a collective should be an organization that merely facilitates the collaborative efforts of patient and caregiver members — including the allocation of costs and revenues. As such, a collective is not a statutory entity, but as a practical matter it might have to organize as some form of business to carry out its activities. The collective should not purchase marijuana from, or sell to, non-members; instead, it should only provide a means for facilitating or coordinating transactions between members.

Well, isn’t that a fluffy mouthful? Let’s be real: Medicinal marijuana is a multibillion dollar business that could potentially help rescue us from a pulverized economy. The state of California stating that a pharmacy “might have to organize as some form of business to carry out its activities” is like refusing to admit your daughter is going to have sex at her senior prom.

Come on, give the girl a condom. Let’s look with eyes wide open at medicinal marijuana as the emerging, booming industry that it is. We need clear, concise laws to be mandated so that the grower, the transporter, the pharmacy, and the patient are at no risk for infringing on the law. And once we can do that, then maybe California — and the nation — can welcome another taxable business into the mainstream.

The give and take

Jenn and I went to the farm with our own agenda. From Los Angeles to Humboldt, we carried with us plans and schedules — an itinerary of what we wanted to accomplish. Humboldt took our plans and bitch slapped them. On the marijuana farm, we weren’t so much seduced by the high of weed, but rather by the buzz of letting go and being in the moment.

On the eighth day of our stay, it became overcast and cold. The forecast called for rain — lots of rain. Jenn and I took this cue and realized it was time to return to L.A. After hugs and promises to stay in touch with our new “trim” family, we packed up our sleeping bags and resin rubber gloves. Then, reeking of ganja, we headed down that winding road. In the redwoods, on a farm up in Humboldt County, we left our agendas, our naïveté, and our phone numbers for next season.

- Follow us on Twitter: @inthefray

- Comment on stories or like us on Facebook

- Subscribe to our free email newsletter

- Send us your writing, photography, or artwork

- Republish our Creative Commons-licensed content