Screams of “$@$^%&*!,” “*&$#@,” and “#$%@^$%,” sirens piercing, fire alarms sounding, reggaeton blaring, and fists banging were all common sounds in the Cheetos-littered halls of Johnnie L. Cochran Jr. Middle School in inner-city Los Angeles, California. The school houses roughly 2,000 students nearly exclusively of Latino and African American backgrounds and from extremely low-income families. It had been named Mount Vernon Middle School after George Washington’s estate that included farms worked by a few hundred African-descended slaves. But in 2006, the school changed its name in memory of its alum, the attorney who defended O.J. Simpson during his murder trial with his “If (the glove) doesn’t fit, you must acquit” catchphrase.

By then, Cochran’s debate team had long disappeared from the school, along with other extracurricular activities. Cochran the school is under-resourced and failing, primarily focusing on keeping the peace and secondarily on raising test scores and receiving funding.

When I first arrived there, I felt a sinking feeling in my stomach and palpable fear. The campus was empty, but the school’s dilapidated state, graffiti, and omnipresent gates and bars worried me. Was this a school or a juvenile detention center, I wondered. Veteran teachers referred to the students as “little terrorists,” or worse, by four-letter names. They warned me and my other fresh-faced newbie colleagues not to smile for the first six months or expect anything from the little “$#@&s” since they were, after all, terrorists. Not surprisingly, after getting such advice, I questioned my decision to join Teach For America, and I tried to get accustomed to my queasiness at Cochran.

Teach For America is a selective national service corps program of recent college graduates who commit two years to teach in under-resourced urban and rural public schools. Corps members do not get to choose their placement location, grade level, or subject area, and although I had hoped for a kindergarten placement, I was given a middle school math and science classroom.

I failed math in college.

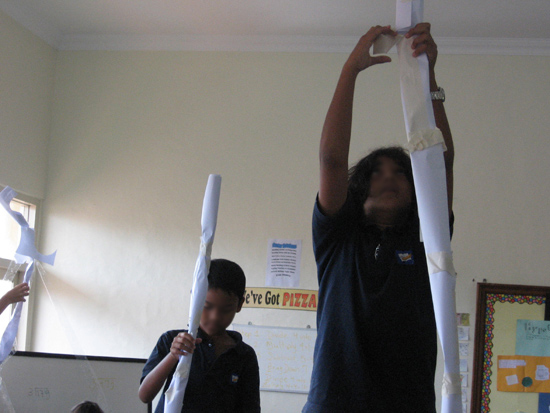

With time, tears, patience, and reflection, I adjusted to the Cochran culture and made great progress with my students. I learned they would live up to the terrorist moniker only if you treated them as such. If you showed them respect, they gave you the same. It was not necessary to break them down in order to attain classroom management, as I had been told. It was much more effective to build students up and engage them in order to attain a peaceful and productive learning environment.

Teaching at Cochran never stopped challenging or rewarding me, and I stuck it out. My crowded classes had as many as 45 students, comprising children of Latin American immigrants who generally did not know English and frequently worked multiple underpaid jobs. These adults put their dreams for their children in my hands and treated me with the highest reverence and appreciation. On Christmas and Valentine’s Day, I drowned in gifts and homemade tamales. These rewards were nice, but the more meaningful ones came in the form of my students’ success and growing confidence.

Most of the students at Cochran had never been told they were smart. They were expected by teachers, parents, and themselves to fail. While I did have parents who had high hopes for their children in “The Land of Opportunity,” others already had internalized a culture of poverty, which led to a resignation to failure. I was shocked at parent conferences where my reports of excellent student performance met disbelief and doubt. I was disappointed that some parents could not see what I did.

The pendulum also swung the other way, with parents in denial of their children’s low skill level, verbally attacking and blaming the very teachers trying to help these children. Dissatisfied parents especially targeted white teachers with the “racism card,” but even Latino and African American educators were not immune to this unfounded accusation.

Although most teachers were not racist, older colleagues occasionally used the “N” word along with subtle racist comments. Accusatory parents nevertheless unleashed their frustration with the institutional racism in the U.S. system overall on teachers with limited resources. In many ways Cochran mirrored the societal issues facing low socioeconomic populations.

Last year, with my two-year commitment having been achieved, I left Cochran hoping to regain a love of teaching at a school not plagued with inner city problems. I found a small international school in Yogyakarta (Yogya), Central Java, Indonesia. Having read in disbelief that the entire school of nine grades comprised only 60 students, I daydreamed about small classes and calm days.

In reality, there are never any calm days as a teacher. While the stress level has definitely decreased, and there are no longer bars on my classroom windows, the school still has gates and security, and we are trained to identify bombs. Here in Indonesia I am not warned about students who are “little terrorists,” but about real ones who throw bombs instead of spitballs. Replacing the lockdowns and fire drills at Cochran are earthquake drills, volcano evacuation plans, and tsunami warnings. In the same way that a Cochran student’s violent and drug-infested home life could affect his or her academic performance, challenges outside my classroom’s control also influence my Yogya students.

My students in Indonesia largely come from expat or mixed homes, and I confidently thought that a lack of economic hardship would lead to easier students, but this is not always the case. Students still come from single-parent homes, and as with my Cochran students, likely have a parent out of the country.

The difference is that in Los Angeles, the parents may have been deported to Central America or unable to cross the border, while in Yogya the parents may be working for non-governmental organizations (NGOs) that send them to another island or back home. The Los Angeles children walk home with friends at 3 o’clock in the afternoon, a key in one hand and a bag of Hot Cheetos in the other. The Yogya children play on the swings while drivers patiently wait with for them—their miniature bosses—holding small Naruto school bags on their adult backs.

Such a “boss” attitude among students toward local staff leaves them shy about disciplining students too harshly for fear of losing their jobs. And no matter how much I stress personal responsibility to my students, I watch their perbantus (maid or nannies) pick up after them outside the bubble of my classroom, my work evaporating in the dry Indonesian air.

Disadvantaged students in the United States often desperately need emotional and academic help. As Ms. Coleman, I was counselor, mother, and teacher. As Ibu Colette at my current school, I hear parents’ demands for help in teaching discipline, cooperation, responsibility, and values—a role in shaping social development.

This will be my last year of teaching. I take my hat off to the men and women who can tirelessly listen to personal problems, negotiate with difficult personalities, sympathize with hurt feelings and body parts, plan engaging lessons, discipline, boost, promote a love of learning, instill values—and explain why “i” comes before “e” except after “c” and how to isolate a variable.

Related Reading

LitWorld: an organization promoting international quality education.

Independent School Support Systems (ISSS): an organization founded by a Teach For America alum from Cochran to help especially gifted students get scholarships to top private high schools.

“Teens get a chance to shine”: a story related to ISSS.

- Follow us on Twitter: @inthefray

- Comment on stories or like us on Facebook

- Subscribe to our free email newsletter

- Send us your writing, photography, or artwork

- Republish our Creative Commons-licensed content