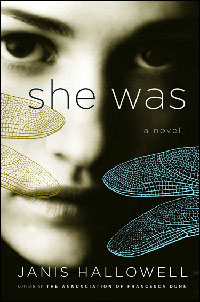

Reconciling the chasm between identity and action in the context of the Vietnam War and the Iraq War is the tight focus of Janis Hallowell’s new book She Was.

Thirty-five years ago, Lucy Johansson was a Kansas-raised young adult living in California. She believed the war in Vietnam was wrong and actively pursued nonviolent protest with fellow students. When the group decided to take its resistance a step further and target buildings after hours, Lucy joined an effort to detonate an explosion at New York City’s Columbia University. Despite her diligence in making sure no one would be harmed by the bomb, there was someone in the building after hours, and Lucy’s offense suddenly bloomed into murder charges.

Fearful and alone, Lucy decided to go underground along with her Vietnam vet brother, who provided food, shelter, and support, thereby sealing his own fate irretrievably with hers. They each took up new identities and new lives. Lucy became “Doreen,” attended dental school, married, and had a child.

But now Doreen’s days on the run are numbered. A fellow student radical has set her sights on her, hoping to trade what she knows about Doreen — one of the last ’70s student radicals still in hiding — to mitigate her own husband’s jail sentence. As the FBI closes in over the course of a week, Doreen realizes her days as a suburban wife, mother, professional, and community volunteer may be over. It’s time to tell her husband and son the truth about who she was.

Woven within Hallowell’s book are several critical subplots, each of which adds to the prism through which the reader is invited to view Doreen.

Her beloved brother Adam, who gave up everything in support of his on-the-lam sister, is haunted by his own memories of service in Vietnam and his life thereafter: from atrocities to lost friends and his father’s high expectations on “being a man,” to enduring the first wave of the AIDS crisis, only to be felled by multiple sclerosis (MS) years later.

Doreen’s family — husband Miles and son Ian — know nothing of her activities in the 1970s and her fugitive status, and find it difficult to judge her for things she did before she was part of their lives. Brief appearances by a couple of Doreen’s fellow radicals illuminate some of the influences that had been at work in persuading Lucy’s involvement with the group. Doreen’s mother, who’s never forgiven her daughter for causing her to lose a son, makes her own judgments crystal clear regarding her daughter and what she’s done.

These perspectives are helpful in developing Doreen as a fully realized character while continuing to allow the reader to draw his or her own conclusions on what Doreen would like to believe about her being a fugitive from the law: that more than three decades of good citizenship somehow mitigates her role in the death of one person at the hands of another.

To her credit, Hallowell’s examination of the roots of identity teases out numerous questions. While she reveals Doreen’s perspective on the idea of identity — that is, will she always be Lucy Johansson, judged by what she did 30 years ago, or can she be Doreen Woods, responsible wife, mother, and upstanding member of her community — at the conclusion of the novel, readers are, for the most part, left to determine for themselves the nature and solidity of an individual’s identity. Through the lens of each character surrounding Doreen, Hallowell weighs whether identity is what is conferred upon a person by others or created by what one becomes through one’s actions, and whether identity is static or fluid over the courses of time and action.

Drawing strong parallels between the 1970s and today, Hallowell juxtaposes Doreen’s antiwar bombing at Columbia with her son Ian’s participation at an antiwar rally protesting American intervention in Iraq. Young Ian, headed off to college, contrasts sharply with his uncle Adam, who more than 30 years earlier felt a heavy civic burden to enlist with the Marines. Likewise, the contrast is vivid between Doreen’s two old friends — one who still clings to her college ideals, while the other wholeheartedly lives what the group used to call the “bourgeois life.”

Hallowell deftly sets up one deeply flawed character against an ever-changing backdrop of American history, and through it, prods the reader to examine the ephemeral ideas of identity and responsibility.

- Follow us on Twitter: @inthefray

- Comment on stories or like us on Facebook

- Subscribe to our free email newsletter

- Send us your writing, photography, or artwork

- Republish our Creative Commons-licensed content