The island filth is clingy and stubborn. It’s an all-out war between me and the layers of Hawaiian dirt that have accumulated on termite-eaten walls. My mop lunges violently at the house that my grandfather built 50 years ago. The aging paint crackles and chips, as bubbling cleaning agents do their grimy work.

Droplets of sweat accumulate on my forehead as I toil away, but I mistake my perspiration for Hilo’s perpetual ocean spray. The air is so moist that some mornings I return home soaked from a run, not realizing that my clothes have been saturated by a gentle morning drizzle.

I take a break under the lines of fruit trees that Grandpa planted in front of the house’s entrance. Mom says that wherever Grandpa walks, vegetation pops up behind him — a green thumb I failed to inherit. For years he nurtured the earth daily so that he could leave us the gifts of his land. Lemons the size of oranges, oranges the size of grapefruits, star fruits, crunchy green mini-apples, and chubby berries wait to be plucked. I sink into the earth’s moistness, my toes slipping out of my slippahs and into papaya mush.

I start clearing rotting branches, fallen leaves and decomposing fruit from the black gravel ground and feel a wave of distress — Grandpa can no longer look out his living room window and watch us as we enjoy the fruits of his years of labor.

The disturbing images of the nursing home video I watched a month ago flood back as I remove mildew that has crept across the walls. “Don’t feel guilty about condemning your elderly loved ones to a cold, windowless home for the dying, where we are understaffed and unhappy,” was the message I took away. Viewing this video at home in the D.C. suburbs, 10,000 miles away from my grandfather’s nursing home room that he shares with a new person (his last roommate passed away), I shudder imagining his life.

He is lying on his back, developing skin sores behind his knees, elbows, and calves because of the constant contact with unfriendly plastic sheets designed to protect the bed from his incontinence.

There is no soul-warming miso soup, with little pieces of tofu and green onions floating on top. No soft, steamy white rice that can dissolve under his toothless gums. Instead, the hospital staff leaves huge chunks of “all-American” white toast that neither his shaky hands can cut nor his gums can manage.

Grandpa’s second-stage dementia triggers a series of daytime naps — the Wonder Bread, left beside his bed, goes stiff and is cleared away before he wakes. On their clipboards, the hospital staff note that he has no interest in eating. He slips in and out of reality, not knowing how or when to ask for food. His remedy? Singing his empty stomach to sleep.

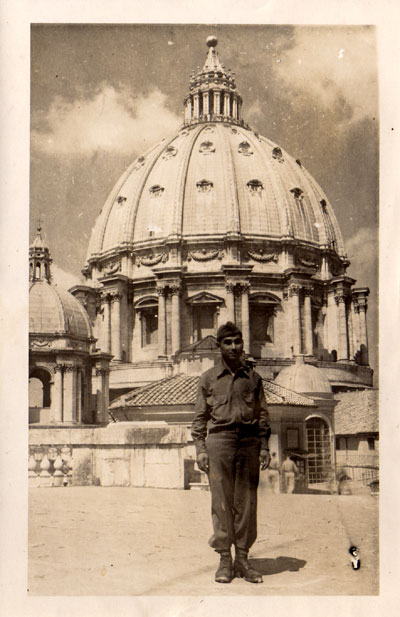

The songs he and his 442nd Purple Heart buddies used as their sustenance during WWII, serve as his now.

“Oh, but Grandpa Kohashi is doing just fine! He watches the birds every day!” the nursing home’s public relations employee tells my mom during a long-distance phone call.

“The birds, the birds — all they can talk about is the birds!” my mom mutters to herself as she hangs up, feeling helpless from the East Coast. “Can’t they comment on his health? His eating habits? His adjustment?” I see guilt emerge in tight wrinkles on my mother’s face. Scrawled on our kitchen calendar are X’s marking the number of days left before we fly to visit him.

And now here I am, in Grandpa’s hometown of Hilo, trying to protect and cleanse his house and the only piece of land I have known throughout my nomadic childhood. It is the plot that has sustained my struggling immigrant family for four generations. Its cement structure has proved impenetrable — withstanding tropical storms and the 1960 tsunami that claimed the life of my mom’s elementary school classmate only a few homes away.

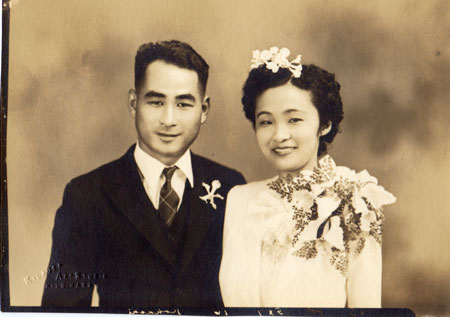

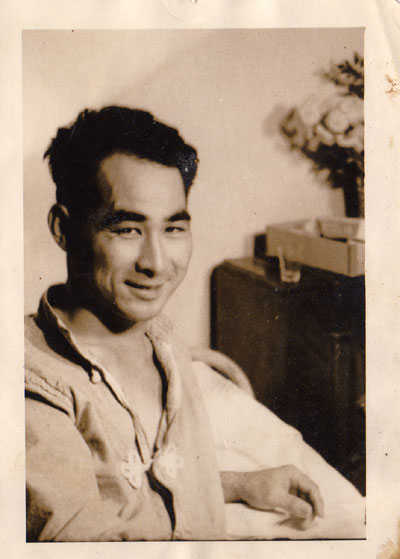

Grandpa’s name tag says, “My name is Hiroshi ‘Coffee’ Kohashi, and my favorite hobby is building my own house.”

I imagine Grandpa pouring wheelbarrow after wheelbarrow of cement into a foundation that would keep for future generations — it was a symbol of the unlimited possibilities for success.

“Are you Susan’s son?” my Grandpa asks my brother. His capacity to recognize our hapa haole faces has disappeared, and so has our opportunity to make him proud. I want to tell him that the reason my younger brother is studying biomedical engineering is that Grandpa inspired us to work everyday, to chip away at our goals until they no longer appear frightening to achieve.

I squeeze his withered hand and peer into his glazed-over eyes, realizing that they never read the postcards I have been sending him for over two years during my travels, tiny acts of gratitude for every achievement I owed to his silent support.

“Hey, take it is easy!” my mom yells out, as she hears paint splintering and ripping off the wall’s surface. I try to refocus and resort to my old childhood game of pretending to be the Karate Kid diligently painting fences white and waxing cars smooth for my Sensei. If the main character, Daniel-san, could follow a path inward and heal himself through the repetitive cleaning motions, I can do the same.

I whisper thanks to Grandpa’s cement walls knowing they will hold his history, our history. The now gentle, circular strokes remove stains, cobwebs, and the coating of neglect. I finally step back.

Stripped clean, the raw white surface now shines like a fresh coat of paint.

STORY INDEX

PLACES >

Hilo, Hawaii

URL: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hilo,_Hawaii

GROUPS >

442nd Infantry

URL: http://www.globalsecurity.org/military/agency/army/100-442in.htm

EVENTS >

1960 Hawaii Tsunami

URL: http://www.pdc.org/tsunami_history.php

MOVIE >

The Karate Kid

URL: http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0087538

- Follow us on Twitter: @inthefray

- Comment on stories or like us on Facebook

- Subscribe to our free email newsletter

- Send us your writing, photography, or artwork

- Republish our Creative Commons-licensed content