I force myself to write a small fraction of all that I heard and saw, because it is important that we all know. Or maybe also because I need to share my own burdens. What can you say about a woman eight months pregnant who begged to be spared. Her assailants instead slit open her stomach, pulled out her foetus and slaughtered it before her eyes. What can you say about a family of nineteen being killed by flooding their house with water and then electrocuting them with high-tension electricity? —Harsh Mander, director of ActionAid India

At 7:43 a.m. on February 27, 2002, the Sabarmati Express was attacked while stopped at Godhra station in the Indian state of Gujarat. While precise events remain unclear, the mix of Hindu devotee passengers returning from Ayodhya, the contested site of a sixteenth-century mosque destroyed by Hindu nationalists, with the Muslim population living around Godhra, was lethal. Two cars were drenched with petrol while a Muslim mob threw stones, acid bulbs, and burning rags at the train. Fifty-eight passengers were roasted alive. Twenty-six were women and sixteen were children.

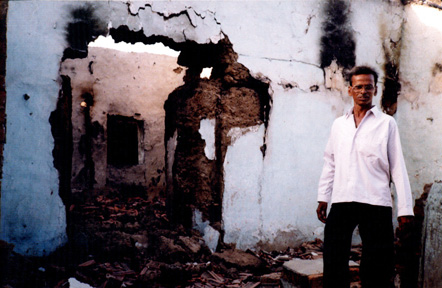

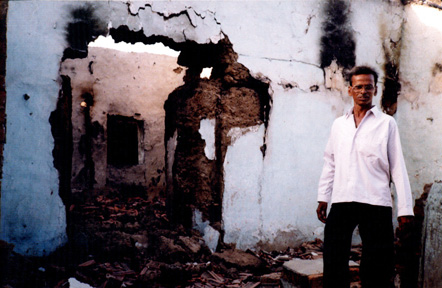

Many have described what followed as a meticulously executed pogrom against the Muslim community. Within hours of the Godhra outrage, shops were looted, houses were burnt, and whole cities came to a standstill. Officials numbered the dead at 800, while independent reports put the figure at well over 2,000. Women were stripped and raped, parents were murdered in front of their children. Hundreds of mosques were destroyed and homes ransacked. Some 100,000 Muslims became refugees in their own country.

A year later, the question remains: What happened in Gujarat? Was it “simply” communal riots? Or was it systematic genocide of a minority population on par with the atrocities in Rwanda and Kosovo? How did this state — Gandhi’s laboratory for nonviolence, source of the wealthiest diaspora of enterprising expatriates — become a petri dish of hate and fear? And why did the vast majority of India’s billion residents remain silent as Gujarat was soaked in Muslim blood? Simple answers remain frustratingly elusive, but it’s clear that the trail of clues leads through the rise of Hindu nationalism, its large-scale acceptance by the average citizen, and the increasing political apathy of the middle class.

The final count of the dead, dismembered, and homeless is only half the story. Initially, the media depicted rioting on both sides. But soon reports trickled in that these were methodical attacks organized by radical Hindu nationalists. Many were members of the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), which heads both the Gujarat state government and the coalition that controls the national parliament. Trucks would arrive full of slogan-shouting young men clad in khaki shorts and saffron sashes and armed with explosives, daggers, and tridents. Their leaders communicated on mobile phones with an unknown “command center,” checking targets against voter rolls and printouts listing Muslim-owned properties. Muslims’ homes and businesses were identified, looted, filled with gas cylinders, and set on fire. Women and children were singled out for the most perverse forms of torture. Mosques and other religious shrines were razed with bulldozers or burned to the ground.

The violence raged well into March and spread to almost all parts of the state. Over 10,000 Hindus were also made homeless either by retaliatory attacks or from being mistaken as Muslim. Twenty-six cities were placed under curfew. Yet Gujarat Chief Minister Narendra Modi kept issuing “all is well” statements while the State Reserve Police sat idle, waiting for orders. There is evidence of police guiding people straight into the hands of rioting mobs. Police sources admit that former parliamentarian Ehsan Jaffrey made frantic calls to the police control room hours before being brutally killed, along with his family, when a mob entered his home. Four constables stood as silent witnesses to the incident. The rest reached the scene two hours after the attack, and the fire brigade only three hours later. The police commissioner cited obstructions along the way as an excuse for the delay.

Those that escaped the murderous mobs faced yet more misery. At the height of violence, the government estimated 98,000 Muslims had been driven from their homes, yet refugee camps received little government support. The humanitarian aid agencies that proliferated during the 2001 earthquake were suddenly scarce. The camps, now officially closed, were run exclusively by bands of Muslim volunteers and a few NGO workers. At present, some estimate that 10,000 Muslims remain without regular shelter. Many are still unable to return to school, access public utilities, or supply themselves with enough food. Pamphlets calling for an economic boycott of Muslims have exacerbated the difficulties of finding work or rebuilding businesses. And to call out for one’s parents as “abba” or “ammi” in Urdu on the streets of Gujarat remains unwise.

The Rise of Nationalism

The BJP-led national government’s response was stunning in its denial. It took many weeks for the national party to respond. And when it finally did, members called upon India’s Muslim population — at 150 million, the largest Muslim minority in the world — to earn the “goodwill” of the majority community. Moderate prime minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee shocked observers when he said, “Wherever Muslims are, they do not want to live peacefully.” In Gujarat, the tragedy gave Hindu nationalist fervor an unprecedented boost. Once a low-key bureaucrat, Chief Minister Narendra Modi took full advantage, campaigning for his second term on a platform of Hindutva, or hardline Hindu nationalism. He won December’s election in a landslide.

The Hindu right focused on an immediate cycle of cause and effect: Muslims killed Hindus in Godhra, and the Hindus retaliated. Some even extended the timeline to prior riots, the ongoing controversy over building a Hindu temple on the former site of the Babri Masjid in Ayodhya, or even the Muslim invasions in 1100 CE. Opposition parties, the national press, and liberal intellectuals were labeled “pseudo-secularists” and “anti-nationals.”

The recent rise of Hindutva, in Gujarat and in India at large, is important to understanding how such a tragedy could have happened. A philosophy of Hindu revivalism, Hindutva seeks to make India a Hindu, rather than a secular, state. Its defining tenets can be traced to a seventy-seven page pamphlet called We or Our Nationhood Defined. Written in 1939 by Madhav Sadashiv Golwalkar, who once headed the RSS (the fundamentalist ideological arm of the BJP), it states, “The non-Hindu people in Hindustan must cease to be foreigners or may stay in the country, wholly subordinated to the Hindu nation, claiming nothing, deserving no privileges, far less any preferential treatment — not even citizen’s rights.” The subtext of the Hindutva war cry is a call for Hindus to assert their religious, economic, and political rights in the face of hundreds of years of subjugation — by the Mughal empire, the British, and then the so-called “pseudo-secularists” of the Congress party. Specious associations of Muslims with the creation of Pakistan, the Sikh nationalist movement, and missionary Christianity feed into the pernicious view that Hinduism is a religion under siege.

For the BJP and its political siblings, the RSS and the VHP (Global Hindu Convention), the killings were a celebration of their very existence. Founded on a Hindu supremacist platform advocating strong anti-Muslim and antiminority sentiment, and tracing its roots to Gandhi’s assassins, the movement has been brewing hatred for decades. Their ideologues echo Golwalkar: “The future of India is set. Hindutva is here to stay. It is up to the Muslims whether they will be included in the new nationalistic spirit of Bharat. It is up to the government and the Muslim leadership whether they wish to increase Hindu furor or work with the Hindu leadership to show that Muslims and the government will consider Hindu sentiments.”

To comprehend the spread of Hindutva, one must first grasp the leadership vacuum that has long been brewing. India claims to be the world’s largest multiparty democracy, yet a corrupt and self-interested political elite shuffle between the ruling party and the opposition in the Indian parliament. Because permission to govern is won based on volume of electoral votes and gerrymandered districts rather than the strength of public opinion, politicians have an easier time targeting specific populations for electoral gains. Voters are made empty promises, bribed with blankets at wintertime, or forced at gunpoint to vote for politicians they hardly know. And then they are conveniently forgotten. Once in power, ministers and members of parliament trade favors to amass wealth, often for generations to come. The BJP government is propped up by a ragtag alliance of political parties called the National Democratic Alliance (NDA). On the opposition benches sit the Congress and the Janata Party, which ruled India for many decades on supposedly secular political agendas until the BJP’s ascension in the mid-1990s.

Within a week of the first riots, the opposition went on a strike to adjourn the parliament, called for a formal censure of the state government, and demanded commissions of inquiry into the massacres. These same instruments of political action — strikes, boycotts, and public inquiry — were implemented during the freedom struggle against the British. But repeated application of these devices in every political conflict has, in Professor Pratap Mehta’s words, “downgraded the currency of protest.” He writes, “What ought to appear like an extraordinary event in the course of our legislative proceedings becomes simply another familiar gesture.”

India Buys In

To lump a billion people, practicing many religions and speaking even more languages, into a predictable and responsible political organism was a challenge on the part of the nation builders — first the British, then the Nehru-led socialists. They began to accentuate every imaginable attribute that could divide people — caste, religion, region, language, income. The government offered customized carrots to each identity-based vote bank: state boundaries drawn to serve linguistic majorities, caste-based quotas in jobs, food packets to the hungry.

The people acquiesced to the command-and-control socialist political system, rewarding politicians with landslide vote margins and a license to misrule. More importantly, the people relinquished the work of social adaptation to the sarkari babus — government bureaucrats, politicians, religious heads, and criminals. Political ideology, religious practice, and cultural norms came to be determined from somewhere above. Freedom was lost again. Thus the way was paved for Hindu nationalists to raise their divisive allegations: the opposition parties want only to appease minorities, to sell out the country, to leave Hinduism vulnerable to Muslim militants and — worse — Pakistan.

India’s deregulation of key industries in the 1990s led to a jump in middle-class affluence, which in turn led to increased consumption. However, the majority of citizens remain poor, with a per capita income of $496 per year. Caught in this transition between postcolonial socialism and a still nascent capitalism were millions of disenfranchised villagers, unemployed urban youth, and bored government officials. Their frustrations and fears were a treasure trove of emotions that could easily be harnessed by political ideology. When provoked by the threat of annihilation of identity, empowered by swords and tridents, and seduced by a feeling of nationalist dogma, this hidden ambivalence spilled over — as numbed apathy at the very least, and bloodcurdling anger at the very worst.

Beneath the veneer of silence and detachment from the blood and gore of Gujarat lies an eerie rationalization of nationalist revival. On Internet bulletin boards, in letters to the editor, or over cups of tea, educated young men (and some women) rationalized the massacres with talk of cause-effect relationships, clash of civilizations, or Newtonian physics — sentiments that resonate with the BJP’s agenda of anti-Muslim propaganda and Hindu revival. In activist Manish Jain’s words, “Their mental make-up and actions are governed by a strange mix of blind hypocritical patriotism, competitive rivalry, consumerist greed, and de-contextualized bits of information.” Who then, he asks, is the struggle between? “Not between ‘Us’ and ‘Them,’ but between ‘us’ and ‘us.'”

For those that believe in the blissful dream of a Hindu state, writer Arundhati Roy has some hard questions. “Once the Muslims have been ‘shown their place,’ will milk and Coca-Cola flow across the land? Once the Ram temple is built, will there be a shirt on every back and a roti in every belly? Will people be beheaded, dismembered, and urinated upon? Will fetuses be ripped from their mothers’ wombs and slaughtered?”

India Opts Out

Many people were shocked and numbed by what was happening in Gujarat. Writers and activists wrote passionately about the unbelievable cruelty and violence. But little happened. Now, a year later, political and social “experts” have moved in to dissect the phenomenon. A witch hunt has begun. They want to find out who started this fire or demolished that building. They continue to accuse BJP political party leaders like Prime Minister Vajpayee and Narendra Modi, some spineless opposition leaders, corrupt bureaucrats, and prominent intellectuals who voice themselves vociferously on both sides of intolerance.

The preferred dosage of intervention is one of technical policy fixes — dismiss the state government, seek a formal apology from the prime minister, call in the Indian army battalions, and impose a stricter code of conduct for press reportage, which in some cases circulated untrue and propagandistic explanations of the carnage. These are real issues, but shouldn’t be Band-Aids placed mindlessly over deep-seated, hidden value conflicts. One of the biggest adaptive challenges lies in the inability of the society at large to consider, in Jain’s words, “the broader processes and systems that shape and harden communal identities and pit neighbors and friends against one another.”

Attempting to pinpoint these identity-forming factors shifts the onus of leadership away from central authority figures, unravels the paradoxes of the competing interests of invisible groups, and probes deep into the contradictions in values so rampant in Indian society. The BJP has marched into power through democratic electoral processes after decades of being a fringe element. Who has given the BJP and the Hindu nationalists the authority to indulge in the brainwashing of millions? It is middle-class India, which forges ahead in its relentless quest for progress, seeking education, jobs, and material accomplishments and believing that political advocacy and influencing public opinion is inconsequential. Yet many hidden contradictions boil within the walls of their own houses — marital rape, child labor, unbridled opportunism, unsustainable environmental practices, and a sense of racial inferiority handed down from the ages.

Many middle-class Indians feel that the deaths in Gujarat are the sad but unavoidable collateral damage of the battle to regain the soul of a nation long suppressed. Ghettoization of Indian society into socially distant bubbles protects those with money from the suffering of the “invisible others”: poor people, minorities, and villagers. How would the middle classes behave if a plane carrying India’s richest man, Azim Premzi, Oscar-nominated actor and director Amir Khan, and cricket star Mohammed Azharuddin — Muslims all — was hijacked by a mob of Hindu fanatics? Their reaction would certainly not be as muted as it was for the Muslim shopkeepers, clerks, and laborers who were killed in Gujarat.

How did we come to be this way? Somewhere down the road, our society failed to perceive the dissonance between the harsh realities facing us and the illusions that our authorities made us believe in: that nationalist identity could somehow promote economic growth; that a nation could somehow leapfrog into global superpowerdom when millions of its children still do not go to school; that somehow all our pains could be linked to the presence of a few pockets of Muslims, Sikhs, and Christians. The pressure cooker of self-examination in which we held ourselves during the struggle against the British has become an open frying pan, steaming out fumes of self-aggrandizement and false nationalism. It took hundreds of years of struggle with others and within ourselves to bring together many ethnicities and create a system of political self-expression. We labeled it “secularism” and “democracy.” Now, secularism connotes the appeasement of minorities, and democracy is the synonym for stuffing ballot boxes with false votes every five years or so.

God, that word which denotes an explicable, multidimensional entity, has been reduced to a menacing idol of Ram with a bow and arrow, reeking of an inferiority complex. We, the people of India, who were supposed to have kept our tryst with destiny, have left destiny to the experts. Someone from above will arbitrate not just the spare change in our wallets, the hymns of our prayers, but also the very content of our character.

UPDATE, 3/8/13: Edited and moved story from our old site to the current one.

- Follow us on Twitter: @inthefray

- Comment on stories or like us on Facebook

- Subscribe to our free email newsletter

- Send us your writing, photography, or artwork

- Republish our Creative Commons-licensed content