Since I was a child, I knew I was going to be a writer. Early on, though, I was ruined by the romanticism surrounding the craft. I’d read too much Jack Kerouac, Hunter S. Thompson, and Charles Bukowski. I did drugs. I drank. I wandered. At first it may have been to emulate my idols, but eventually it became about survival: running fast and hard from the horrors of an abusive home.

I don’t recall ever making the connection that all of my literary heroes were straight white men, but in the back of my head I knew that so much of how the world opened up for them would never be in the cards for me. But I kept writing, filling up composition books, not thinking about getting published so much as trying, word by word, to patch up my life.

In high school, several teachers took an interest in me, despite the fact I was a miserable fuckup who barely showed up to class. I read all of the writers they believed a girl like me should read. The men gave me Tennessee Williams, William Faulkner, Fyodor Dostoyevsky, Albert Camus. The women gave me Kate Chopin, Sylvia Plath, Anne Sexton. Not once did any teacher ever hand me a book by a writer of color.

I now understand this experience is hardly unique to me. If it weren’t for one of my oldest friends, Jessica Rodriguez, loaning me Loose Woman by Sandra Cisneros in high school, I would have never known a Latina could be a writer. I mean, I knew Latina writers existed—they were my friends, fellow notebook scribblers—but I don’t think it ever occurred to us that one day we could hold each other’s books in our hands.

Diversity in literature is something I’ve been thinking about quite a bit lately. Last month I attended a workshop run by the Voices of Our Nation Arts Foundation (VONA), which sponsors programs for writers of color working in a variety of genres. I sat at the orientation looking around in disbelief at more than 150 writers crammed into a room at UC Berkeley, thinking, “Holy fuck, I had no idea there were so many of us.”

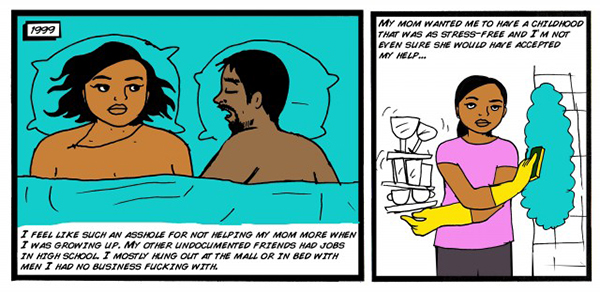

I was there because of the weekly comic strip I write with my best friend Julio Salgado. Liberty For All is his baby. In its early days, the queer, undocumented artist drew and wrote it himself and posted it on his Facebook page. When the comic was picked up by CultureStrike, I was brought on as the writer, giving the two of us the opportunity to work on our first project together after nearly ten years of friendship.

Liberty, the strip’s main character, is a writer without much of a filter. She is sometimes Salgado. Sometimes me. Sometimes our friends, lovers, or family members. She is never a stranger to us. By featuring her story, week after week, we hope she is seen as the quirky, complicated, sometimes problematic character we know her to be, rather than a laundry list of oppressions. But because of those less-than-conventional details of who she is—chubby, brown, undocumented, queer, feminist—I worry that mainstream audiences aren’t capable of recognizing her humanity.

Junot Díaz, the celebrated Dominican American author of The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao and one of VONA’s founders, has spoken out about the tough environment writers of color face. In a recent New Yorker piece—an excerpt from an anthology of writing from VONA attendees and instructors—Díaz describes his particularly miserable experience studying in an MFA program: “That shit was too white.” It’s the “standard problem” of MFA programs everywhere, he adds. Díaz brings up the story of Athena, a Caribbean American woman he praises as a “truly gifted writer.” She dropped out of his program because it was simply too challenging to be a woman of color in that space. Over the years, he looked for Athena’s work, but it appeared that she had chosen not to pursue writing. Díaz seems to recognize the tragedy of this, if only in the distant way a man who “made it” can.

How much better are things today? The women’s literary group VIDA does a yearly tally of the number of women writers in various mainstream literary publications, from the Atlantic to the New Republic—both of whose bylines were more than two-thirds male in 2013. Inspired by this hard-numbers approach, Roxane Gay set out to find out where things stood for writers of color. She found that nearly 90 percent of the books reviewed by the New York Times in 2011 were written by white writers. (Today, few writers of color can be found even in the pages of liberal magazines, which may laud diversity in theory, but do not actually practice it.)

Gay also pointed out another issue: the identity hierarchy. “Race often gets lost in the gender conversation as if it’s an issue we’ll get to later,” she wrote. Yes, progress is slow, but it’s always the most needed voices that are forced to wait. And as we push for a racial mix that better represents the world we live in, does that mean we’ll also need to “get to” queer and transgender writers later?

At least people today are more willing to speak out about these issues—on social media, in particular. In May, the #WeNeedDiverseBooks hashtag went viral after it was announced only white writers would be featured at BookCon, a new reader-focused book festival held in conjunction with the annual trade show BookExpo America. It wasn’t the first time BookCon organizers had come under fire. A month earlier, they had put together a panel on young-adult literature composed solely of white men.

Another diversity-related dustup blew up on Twitter in May when writer Daniel José Older reacted to criticism of a story in Long Hidden: Speculative Fiction from the Margins of History, an anthology he co-edited. A review chided one of the anthology’s writers, Troy L. Wiggins, for relying too heavily on “phonetic dialect,” calling it a “literary trick” that rarely works. Older tweeted that the reviewer was unfairly coming at a black writer for using AAVE (African American Vernacular English), even though critics have long called white writers—from Joyce to Shakespeare—“brilliant” for using vernacular in their prose. He and Wiggins, Older wrote, are “trying to stay true to our voices in a white ass world.”

In the comic strip Julio and I work on, many of the characters are queer, undocumented, body positive, sex positive, transgender, and people of color. They suffer from mental health issues. They live below the poverty line. They do bad things. In other words, they are messy and beautiful, just like our real-life communities.

Julio and I never had a conversation about being all-inclusive, but sometimes we get commended for our “diverse” comic. No doubt the nine other people in my graphic novel writing workshop—eight of whom were women—encounter the same weird praise. And that’s just it, really. When you give people at the margins the opportunity and platform to tell their own stories, what is reflected will look like intentional pushback against mainstream narratives. Our stories only seem revolutionary because they so often go untold.

At VONA, our instructor Mat Johnson told us we can’t hide behind our oppressions. We have to be good writers. Our only hope of getting mainstream readers to take interest in stories featuring people of color is by tapping into the human condition, those seemingly mundane and yet monumentally important life events that connect us all—and that magically render gender, race, culture, and class unimportant.

- Follow us on Twitter: @inthefray

- Comment on stories or like us on Facebook

- Subscribe to our free email newsletter

- Send us your writing, photography, or artwork

- Republish our Creative Commons-licensed content