When the Soviet Union began to crumble a quarter-century ago, more than a dozen of its former republics gained their independence. But in the South Caucasus—that much troubled limb of land that, depending on your perspective, either connects or divides the Eurasian continent—the withering of Soviet rule meant the escalation of war. In the early nineties, Armenia and Azerbaijan fought over Nagorno-Karabakh, a mountainous, landlocked region inhabited mainly by ethnic Armenians but recognized by the United Nations as part of Azerbaijan. The conflict left as many as 25,000 dead and a million displaced from their homes.

Since then, attempts to broker a lasting peace between the two countries have failed. Ethnic hatreds go far back, entangled as they are with Armenian hostility toward Turkic people and anti-Armenian sentiment that fuelled the Armenian genocide conducted a century ago in the Turkish-ruled Ottoman Empire. Although Armenia and Azerbaijan signed a ceasefire in 1994, dozens continue to die each year in frontline skirmishes. And the situation has worsened in the past few months, with the fighting intensifying and the threat of a large-scale conflict becoming more palpable. “We expect war every day,” said the commander of Karabakh’s defense forces, Movses Hakobyan, in a recent interview. “And the goal of our army is to stand ready for it.”

Onnik Krikorian is a British-born journalist, photographer, and media consultant who has worked for years to promote peace between the two countries. His independent-media platform Conflict Voices brings together grassroots activists, bloggers, and citizen journalists from around the region, who use social media to challenge stereotypes and encourage dialogue between ordinary citizens of both countries.

Normally, Azerbaijanis and Armenians have very limited contact. Armenia is an oligarchy, rife with electoral fraud and poverty; Azerbaijan is a dictatorship. Each country routinely demonizes the other in the media. Krikorian, whose ethnic surname comes from his Greek Armenian father, emphasizes the need for an alternative view of the conflict, one not swayed by the propaganda on either side. Through his work with Conflict Voices, his role as a consultant and trainer, and his own writing and photography, Krikorian has sought to build that “third narrative” piece by piece, documenting life in communities where ethnic Azeris and Armenians still live and work together peacefully.

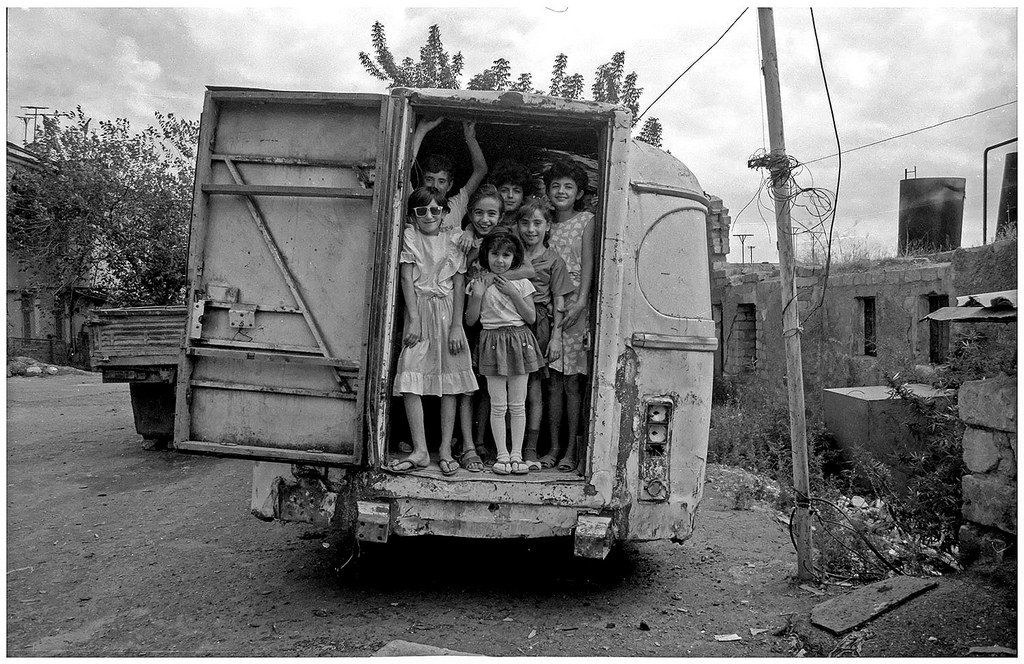

Nowadays Krikorian is based in Georgia—a country he describes as something of a neutral ground between its two warring neighbors. He has reported extensively on his city of Tbilisi, including recent pieces on the lives of its street kids and an environmental protest camp in Vake Park devoted to stopping the construction of a hotel. Yet his work as a journalist has also taken him to the farthest corners of the region. His photography tells the stories of the forgotten people of the South Caucasus: those living in remote villages, foraging landfills, or dwelling in institutions.

In The Fray spoke with Krikorian about his days toiling on Web 1.0 websites, his first awkward but breakthrough meeting with young Azerbaijani bloggers, his hopeful pragmatism about the ongoing conflict, and why he thinks photojournalism is, at its heart, about empathy.

How did you first get into photography, and what was the process that led you to the South Caucasus, doing the kind of work that you do?

When I was in my early teens I saw the work of Don McCullin, a British war photographer, and Dorothea Lange, who photographed poverty in the Dust Bowl in the United States in the 1930s. It just blew me away. These images for me represented what the power of photography was. They weren’t just of foreign wars, they were also of poverty in the United Kingdom, for example, and it had a major effect on me. That was what really pushed me into photography.

I started at the Bristol Evening Post doing paste-up and sub-editing. Eventually I decided to move to London. I got a job at the Independent newspaper, but again on the production side of things. It was then that I got to the South Caucasus. The ceasefire in Nagorno-Karabakh had just been signed, so I went to the picture editor and said, “Listen, there’s a humanitarian-aid flight going to Nagorno-Karabakh. Let me go.” And the guy said, “Sure, okay.”

When I came back, Mosaic—the web browser that popularized the Internet—had been released. I took a look at this web browser and thought, Wow, I understand where this is heading, and I need to do this. So in 1994, I set up my first Internet site, on the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict. I also became involved with the Kurdish Human Rights Project, following a chance meeting with some Kurdish activists in London.

In 1998 they asked if I’d like to go to Armenia to research the human rights situation of the Yezidis, the largest minority in Armenia [a Kurdish religious group now in the news because of their persecution in ISIS-dominated Iraq —ed.], and while there it was obvious that there was very little reliable information coming out of the country. I was struck by the poverty, the corruption, and other issues that no one was really reporting on. So that’s when I decided to write. Because ultimately, I felt that these issues need to get out there. I was offered a job with the United Nations Development Programme and moved to Armenia in 1998. That’s when the sort of work I do now started.

What languages do you speak?

I speak English and some Armenian. I learned Armenian when I was in Armenia. While my dad is ethnic Armenian from Greece, my mum is English. My parents divorced when I was about a year old, so I was never brought up by Armenians, and I never had any contact with Armenians until I was about twenty-one, when I got in touch with my father again. I don’t know what that really says. Maybe I have a different view of how identity works.

This concept of ethnicity in the South Caucasus is a concerning thing. People relate to each other here based on their ethnic group, rather than, you know, “You’ve got the same biological makeup as me.”

How did Conflict Voices come into being?

In 2007 I was Caucasus regional editor for an organization in the United States called Global Voices. I would put together posts about issues that were underrepresented in the regional and international media from the South Caucasus—for example, about gay rights, women’s rights, or the flawed process of elections in the region. But in 2008, Facebook started to emerge in the region, and then things really got interesting. You could basically form relationships across borders online.

I was still based in Yerevan, Armenia. As the regional editor for Global Voices, how could I do anything referring to Azerbaijan without knowing what was really happening there, or without even being in contact with any Azerbaijanis? It’s just not professional, and it’s definitely not possible to have a clear view of the region if you don’t speak to people from the other countries. So I ventured up to Tbilisi and made contact with some Azerbaijani bloggers at a BarCamp. It was very interesting. You had the Armenian contingent, who would be standing about twenty meters away from the Azerbaijani contingent. They were just totally separate. I thought, Well, this is bloody stupid! So I decided to approach the Azerbaijanis. I had my camera on me. They thought, This looks like a photographer, let’s give him our cameras and ask him to take pictures of us together.

I handed them their cameras, and they said, “Thanks very much, where are you from?” I said. “I’m from England.” They said, “What’s your name?” I said, “Onnik Krikorian.” Deathly silence. But people are people, and there’s always that initial thing when you have stereotypes and whatever. You don’t know how to react in such a situation. After ten seconds, they say, “Thanks, stay in touch. Could you send some of the images you took with your camera?” So I found them on Facebook and made contact with them. Suddenly, a world in Azerbaijan through young Azerbaijanis was opened up to me. And not surprisingly, they weren’t very different from Armenian youth.

They’re not totally preoccupied with the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict, and they have the same interests as any young person does—mainly posting about music, films, university, or whatever. I saw the potential of social media to break down stereotypes and thought, if only a young Armenian in Armenia could see what a young Azerbaijani is doing. They would see that actually each side is not a monster, each side is not perpetually thinking about armed conflict. In that sense, social media was incredibly revolutionary.

I had a foot in the door of Azerbaijani social networks. And as a journalist, the more they saw my work, the more I think they understood that I wasn’t a threat. Trust and relationships were built, and my material was shared. I thought, okay, something really has to be done now, something proper, because this is a very wonderful, personal tool for connecting people.

Has this affected your view of the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict?

Yes, it’s changed my view of the conflict. Don’t get me wrong—it’s also a really depressing situation, with no solution anywhere in sight. In 1994, when I returned to London from Nagorno-Karabakh, analysts were telling me, “In twenty years, the conflict will be solved.” Well, it’s now twenty years since then, and the conflict is nowhere even close to being solved. I’m not even sure it’ll be close to being resolved in another twenty years.

So do you just envision a continuing standoff, or do you think something else is going to happen?

I think the standoff continuing is, unfortunately, a safe bet. What some are concerned about, however, is whether hostilities will resume. I think the consensus is that no side will start a new war, but that there’s a danger of an accidental war when a skirmish on the border spirals out of control. But despite how depressing the situation looks, I can at least see in the interactions I have with Azerbaijanis and Armenians, that there is a—albeit small—group of progressive, open-minded people on both sides.

They communicate with each other, and some meet face-to-face. In Georgia, of course, you have ethnic Armenians and Azeris who have absolutely no problem with each other at all.

You have now been based in Georgia for two years. Was this a tactical decision?

Georgia is very different from Armenia. There’s a more liberal and freer environment here. I’d been visiting since 1999, and even then—when it was a failed state, when it was criminal, when there were problems with electricity—there was something about Tbilisi that I really loved. Yes, I knew all the problems, and it was inconceivable that the Rose Revolution would happen and things would start going in the right direction. There was something I liked about the place, and I always knew I’d probably end up here. My Armenia-Azerbaijan work is another reason. This is the center of the South Caucasus, the place where everyone can intermingle.

It’s difficult for Azerbaijanis from Azerbaijan to get into Armenia, and it’s even harder for Armenians to go to Azerbaijan. It’s a horrible conflict and people don’t mix. People-to-people contact is an incredibly important—if not the most important—component of reconciling differences and finding a peaceful solution. And it’s the one thing that the citizens of both countries are prevented from doing—except in Georgia. There are Armenians from Armenia and Azerbaijanis from Azerbaijan mixing here. Not thousands, but it does happen.

I think this is the strength of Georgia. It’s always been the heart and soul of the South Caucasus.

I remember reading your articles about Tsopi, the Georgian village co-inhabited by ethnic Azeris and Armenians, and about the Azeri-Armenian teahouse in Tbilisi.

You know, you have this in Georgia. But when you have really intense nationalism and propaganda in Armenia and Azerbaijan, both sides cannot see eye to eye or find any common ground. Some would argue this is by design. Both governments have a vested interest in maintaining the status quo, because it allows them to cling onto power. They’ve come to power on the back of the Karabakh conflict, and presidents have lost power on the back of it, too. These are the things that have defined the leadership in both countries. But there are alternative voices emerging, and that’s the most important thing for me. Ten years ago these alternative voices didn’t have a space, online or off, but now you have alternative media outlets in both countries. I would even argue that despite there being more anti-Armenian sentiment in Azerbaijan than anti-Azeri sentiment in Armenia, there’s an even larger group of alternative young Azeris who are more open-minded than their counterparts in Armenia.

There could be very many reasons for this. It could be because there’s a more oppressive regime there. But the youth movements, the alternative voices in Azerbaijan are incredibly impressive—and they face the greatest risks in the entire South Caucasus for what they’re doing.

You’ve covered a lot of different stories around Armenians and Azeris living together, but also around social movements in Georgia—like the Vake Park protests—as well as street kids in Tbilisi, and institutions and asylums. How do you decide which stories you’re going to cover?

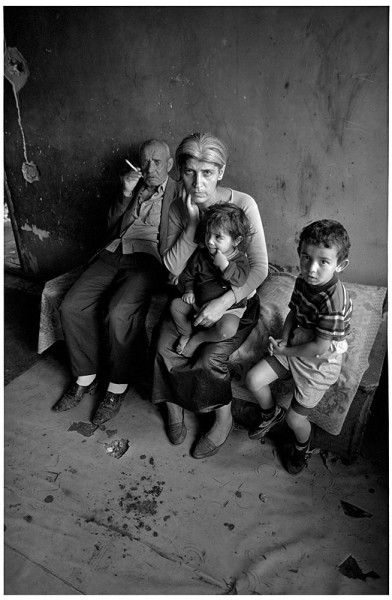

I stumble upon something and see there’s something wrong and that no one is covering it. Actually, the problem of vulnerable children in residential care started in Armenia, as part of a big project I did on poverty in Armenia. There’s a lot of poverty. I saw this and I was very shocked by it. I worked with organisations like Médecins Sans Frontières [Doctors Without Borders], and that took me into the issue of the institutionalization of children. In 2007 I came to Georgia to look at the situation here. They had the process of de-institutionalization, so it was an interesting contrast.

Vake Park was an impressive display of a non-politically partisan social movement that managed to attract the involvement of everyone. I’m used to movements in Armenia being politicized, and for me that’s not the way you achieve social change. Maybe it’s a part of it, but you need grassroots nonpoliticized movements. Vake Park is still going on, the hotel has not been constructed, and they’ve still got their camp. It was a pleasure to document something like that, as well as an interesting story.

The street kids project is ongoing. There’s a lot of kids on the streets of Tbilisi. These kids are not necessarily sleeping on the streets. The majority do have homes, but are from poor families. They’ve got no choice but to beg on the street from early morning until late at night. The street is not a safe place for a kid. Under UNICEF’s definition, they are still street kids. They’re great kids. I really enjoy hanging out with them.

It seemed that you had a strong rapport with those kids—and, in other stories, with the people who live by salvaging from landfill sites, or who live in small villages like Tsopi and Sissian. How do you create a level of trust that allows you to take such intimate portraits?

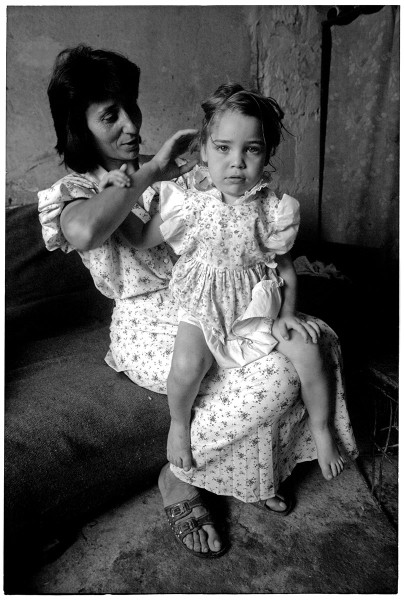

You don’t necessarily try to gain their trust. You either have empathy with them, or you don’t. A lot of photojournalism is about empathy with a subject. Unless, of course, it’s a battle raging around you, or police beating protesters—then you don’t really have empathy with the policeman—but for those sorts of social issues, you need empathy. You can tell if someone’s being open with you or not. Also, it takes a lot of work. In some cases you have to spend days for them to get to know you. There were times documenting poverty in Armenia and especially at the landfill sites that I wouldn’t take any photographs, because they didn’t want pictures taken. Why would someone who’s taking rubbish off a landfill want their picture taken? Why would someone who’s living in extreme poverty want their picture taken? Of course they don’t want their picture taken. There was this horrible hostel in Yerevan, and this beautiful little kid in rags. I ask to take a picture and her mother says, “No, no, no!” And she drags the kid away, takes her into the only other room, and then emerges with her in this clean, immaculate dress. I’ve got a picture of the mother with the kid sitting on her lap, brushing her hair, and she’s dressed beautifully, because they’ve got pride still. Maybe that picture works because it shows that. I can’t go into someone’s home and intervene in their lives, then just walk out. I would also go back many times, to see if their lives had improved.

Have there been any improvements?

The poor people, no. There is the building of the homeless shelter, but that’s not really a major success story, because the government, being the Armenian government, decided to build the homeless shelter right on the outskirts of the city, where no homeless person can actually get to. Homeless people stay around markets, and there’s a reason for this, and that’s because homeless people go through the bins later looking for discarded stuff. And buses won’t take homeless people. And taxis, even if they could pay, don’t take homeless people. So it seemed like a success, but in reality it didn’t really do much to achieve a solution.

I guess the main success story for me is the number of Armenians and Azerbaijanis that I’ve managed to connect who would never have done so without me acting as a bridge. You need someone to break the ice and to bridge that divide. I think that’s the most successful thing I’ve managed to do. Of course, the conflict is nowhere near resolution, and however many people I manage to connect, it’s still not a critical mass. I was recently at a closed meeting on Nagorno-Karabakh, and a very bright guy from Azerbaijan simply noted, “There’s no peace movement. There’s no demand for peace. And NGOs, it’s time for you to stop sitting around, patting yourselves on the back, talking about the projects that you’ve done, because they’re really not changing much. There really is no genuine grassroots peace movement in the South Caucasus, and especially Armenia and Azerbaijan, and now you guys need to work on creating one.”

Maybe that’s what I hope I can contribute to. To try and make this bigger. Obviously I can’t do it on my own, but maybe as part of a bigger process that can finally sort out the mess that is the Nagorno- Karabakh conflict. It’s a major obstacle to the development of both countries. The conflict will be over one day. It cannot last forever, and so I’d like to think that my work can be part of the process that brings that day sooner. Of course, whether I’ll see it in my lifetime is still unclear.

This interview has been condensed and edited.

Jo Magpie Jo Magpie is a freelance journalist, travel writer, and long-term wanderer currently based in Granada, Spain. Blog: agirlandherthumb.wordpress.com

- Follow us on Twitter: @inthefray

- Comment on stories or like us on Facebook

- Subscribe to our free email newsletter

- Send us your writing, photography, or artwork

- Republish our Creative Commons-licensed content