- Follow us on Twitter: @inthefray

- Comment on stories or like us on Facebook

- Subscribe to our free email newsletter

- Send us your writing, photography, or artwork

- Republish our Creative Commons-licensed content

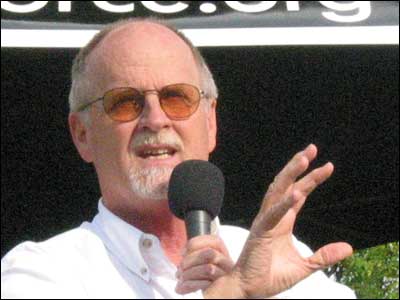

Rev. Mel White penned the life stories and speeches of conservative Christian superstars like Pat Robertson. His religious leaders publicly and vehemently condemned gays and lesbians, and White tried to overcome his homosexuality with exorcisms and electric shock therapy. In 1993, White came out as a gay man and denounced the politics of hate in the evangelical church. Now, 15 years and two books later, White spearheads Soulforce, an organization for lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender acceptance in religious communities.

Here, White discusses the latent power of the Religious Right in the forthcoming presidential election, his antipathy toward civil marriage, and the rationale behind the Religious Right’s homophobia.

Interviewer: Anja Tranovich

Interviewee: Rev. Mel White

What prompted you to come out after many years of marriage and trying to lead a heterosexual life?

I don’t ever remember making the decision to come out. After all the years of marriage, therapies, and counseling to overcome the demon, I finally sliced my wrists. Driving back from the hospital, my wife said, “You know, you are a gay man.”

We separated, and slowly I started learning about my sexuality. First, I learned to accept it, then to celebrate it, and finally, to share it, as the truth dawned on me that it is a gift from God, just like heterosexuality is a gift from God.

In 1993, I had my public coming-out. Since the Religious Right that I had worked for for so long refused to listen to me, I wrote my book, Stranger at the Gate: To Be Gay and Christian in America. I needed them to hear me, and the book was a national coming-out.

I know you were raised as an evangelical Christian. Do you still consider yourself one? What does that label mean for you?

I consider myself an evangelical, but I don’t advertise it widely.

I am an evangelical, meaning “good news recipient and bearer” — that God loves humankind. I’m trying to both appropriate good news for myself in my own life, follow Jesus as best I can, and share the good news.

You’ve said in the past that gays are the top villain right now for the Christian Right. Do you still think that’s still accurate?

I think the Christian Right is widening its target to include illegal immigration and abortion doctors in terms of the amount of vitriol, but homosexuals still take the biggest beating. We [at Soulforce] monitor the Religious Right media. We’ve got filing cabinets filled with data. Much of this is a caricaturizing of homosexuals, condemning and demonizing.

Why have they targeted homosexuality? Where does that impulse come from? Is it really rooted in religious conviction and a literal reading of the Bible?

It is very important that we acknowledge they are sincere in their fears about homophobia — it is dangerous to see them as insincere. They are true believers.

They think if we break out of the sexual roles we were meant to play from the beginning — if a man takes on the role of a woman, which is how they view homosexuality — and the country accepts it, then the country is accepting a grave sin, and God can no longer bless the country.

What is your response to those sentiments?

Empirical and biblical data don’t support the position that homosexuality is a sickness or [a] sin. The Religious Right has to ignore all the data to make [a] case against us, and misuses the Bible to condemn us. We must remember that the Bible has been used throughout the centuries to support intolerance, and now it is being used again to support homophobia.

You spent some time a few years ago talking about homosexuality with Fred Phelps of “God hates fags” fame. What was that like? Was it possible to have a dialogue?

Fred Phelps is a former [American Civil Liberties Union] ACLU lawyer. He has a doctorate. He reads in Greek and in Hebrew. He has a massive theological library.

His favorite preacher is Jonathan Edwards, and Jonathan Edwards dangled sinners above fiery hell to awaken them to their “lostness.” He believes anyone who accepts his or her homosexuality is lost [and] needs to be awakened. We spoke quietly and calmly for about two hours on his views.

He is a Calvinist, and his sermonizing uses fear to drive people into the arms of God. He looks like a nutcase, but he really isn’t. He has a rationale for what he is doing, and that’s what is most frightening. He is not only a sincere believer, he is following a historic tradition.

You are about to celebrate the 10th anniversary of your organization, Soulforce, and you first spoke out publicly against Christian homophobia 15 years ago. What has changed since you started doing this work?

Well, now we are having internecine wars not seen 15 years ago over gay issues. Large churches are splitting apart so that they don’t have to accept gays. Famous pastors and preachers are getting kicked out for supporting [ordination] of gay leaders.

There is a growing mass of allies, gay and straight alike, fighting the battle. It’s true that the media has changed a lot, but there is a strong backlash. Now people have discussions about whether clergy should deny membership to homosexuals. It is absolutely heresy to keep people out of Christ’s church!

There is a terrible threat to fall backwards. We could easily be completely taken over by these well-meaning fundamentalists.

Is the extension of civil marriage rights important to you — would you like to legally wed your partner?

Absolutely. We have been together 27 years now; I am looking Father Time in the eye. If we had equal rights, he would get my social security. As [it] is now, he will lose tens of thousands [of] dollars a year, those kinds of things.

We can’t have a will that in any way looks like marriage, we can’t do our income taxes together, we double pay. It’s just bizarre that we don’t have those rights. It’s not about religion; it is about civil rights. We are not arguing for civil unions, it has to be called “marriage” to have equal laws.

We have been married in the eyes of each other and in the eyes of our families and in the eyes of God. We have marriage; we just don’t have the civil rights to go with [it].

Do you have a take on the upcoming presidential elections? Are we entering into a new era where the Religious Right doesn’t have as much political power?

I think the Religious Right doesn’t have a political candidate. Therefore, they are simply waiting. Their organizations are still very much in place, accumulating funds and members and power. They don’t have a candidate, and they are divided over McCain. But they are not dead, just latent, waiting.

And evangelical work has changed somewhat. It has broadened. They are more interested in issues of the environment and the earth, poverty, HIV-AIDS. But among even progressive evangelicals, none have come out for gay marriage — Jim Wallace, Tony Campolo — none of them is our ally.

I am offended when Christians suggest gays are unworthy of marriage and therefore second-class. It creates an environment where gays are killing themselves when even progressive Christians say your marriage isn’t worthy, is sinful; in other words you are sinful, unworthy.

I’m really offended when people think they are taking a giant step forward when they call for civil unions and refuse to call them by their right name. It is true that some are calling for civil unions, but when they say our relationship is not worthy of marriage, it is demeaning. I’m being demeaned by my friends as well as [by] my enemies.

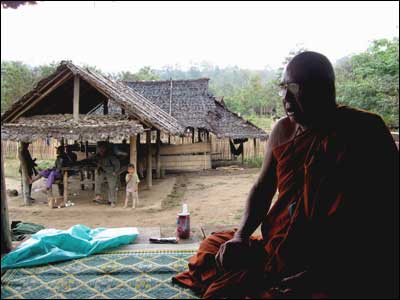

In a jungle encampment in eastern Myanmar, 67-year-old monk Saw Wizana sits meditating in orange robes. Behind him, hundreds of men with semi-automatic weapons line up in military formation and march in circles around a field. They are preparing for another battle against Myanmar’s military government.

Saw Wizana and the soldiers are Karen, the largest ethnic group in Burma. They have been fighting the government for 60 years in what has become the world’s longest running civil war. While tens of thousands of monks caught the world’s attention last August and September for their massive nonviolent protest, some Buddhist clergy in Burma — including Saw Wizana — insist that violent resistance is the only viable strategy against the ruling junta. Today, monks from both schools of thought continue to battle the military dictatorship. They say they belong to the same revolution.

Saw Wizana argues that as a Buddhist monk, he supports the controversial Karen armed struggle because he says it saves lives.

“We want to use a peaceful way like Martin Luther King, like Gandhi, but the military regime doesn’t accept it. That’s why we have to pick up arms,” he said. “Of course we want peace. Everyone wants peace. But it doesn’t work. That’s why we need weapons. We only use them to defend ourselves.”

The Saffron Revolution, brutally suppressed

The Buddhist country of Myanmar, named Burma until 1989, is among the most oppressive in the world. Pro-democracy advocates are routinely imprisoned, and ethnic groups like the Karen are regularly attacked by the military government.

Until recently, because of the government’s stranglehold on dissent, only the Karen rebels have openly confronted the dictatorship. But in August and September of last year, when tens of thousands of monks became involved in what originated as pro-democracy and student protests against rising fuel prices, a nonviolent resistance was reborn.

After days of nationwide protest dubbed the “Saffron Revolution,” the monks were brutally beaten and shot at by the military.

Monk Saw Wizana says the tragic result of September’s protests, in which at least 31 people were killed and hundreds imprisoned, proves that nonviolent resistance won’t work against the Burmese dictatorship.

“Nearby countries like Sri Lanka, Laos, Cambodia, and Thailand — they are all Buddhist countries, and they wouldn’t hurt monks,” he said. By contrast, in Myanmar, he added, “monks were tortured by the military soldiers and forced to worship their torturers.”

Buddhism and armed struggle

Saw Wizana — an imposing, heavyset man with gold wire frame glasses and rolls of orange fabric — has been a monk for 37 years. He spent four years in prison between 1984 and 1988, and was forced into hard labor as punishment for challenging the government.

“I was in the forest with several young students I was teaching. When we were sleeping, the military shot my students because we are Karen,” he said. “I told them they were breaking the law, and because I talked back to them, I was put in prison.”

He insists the Karen armed struggle is not in conflict with Buddhism because it is protecting life.

“We have to use it together with religion,” he said. “Use weapons for defense and religion to keep us courageous.”

Of the armed groups that have fought Myanmar’s dictatorship, all but the Karen have surrendered. The Karen National Union (KNU) comprises Christian, Buddhist, and Animist ethnic Karen people, and has suffered major troop losses over the decades. The KNU estimates its forces are outnumbered by government forces at least 25 to 1.

The KNU is also criticized for planting landmines, recruiting child soldiers, and instigating violence in civilian areas — accusations they deny.

At KNU headquarters, Saw Wizana is known as “Monk Rambo.” Other monks say they too understand the Karen armed struggle. One of them, 53-year-old Oh Bah Seh, was a leader of last year’s protests and says he does not condemn the Karen war. He is neither Karen nor part of the KNU movement. “No one wants violence, but because of the inhumane persecution [by] the government, that is why some came to take arms to fight the evil system.”

He, however, practices nonviolent resistance, like most other Buddhist monks. He says that as he was being beaten with a stick during the September protests, he still continued chanting loving kindness toward his oppressors.

Nonviolence is key, others say

Twenty-eight-year old Ghaw Si Tha, another leader of September’s peaceful marches, said nonviolence is key to a Buddhist resistance.

“We must go on chanting love, as we are monks. Even though they use force, even though the regime doesn’t follow the Buddhist precepts, we have to be faithful to love,” he said. “We believe that only love can produce success. That’s why we march with loving kindness, peacefully without violence.”

In Myanmar, political resistance by Buddhist monks dates back to British colonial times when Buddhist clergy helped fight for independence. The Buddhist clergy are a venerated group, seen by the general public as leaders. Today, Myanmar’s 400,000 monks are a group outnumbered only by the military.

Although unwilling to give specific details, monks Ghaw Si Tha and Oh Bah Seh say there are plans for future nonviolent protests in Burma. Many suspect August 8 — the 20-year anniversary of the massive pro-democracy protests, as well as the opening of the Beijing Olympics — to be a day to watch in Myanmar.

“Now, in this way, we Buddhist monks are also doing the same thing as the Karen fighters,” said Oh Bah Seh. “Revolution.”

the meek, the meek

i.

in him like the sewing needle of god’s mother; is lightning.

in you a koan.

ii.

now that she wants the surgery removed

they tell her

the womb

is a hook

that looks like a womb.

iii.

everywhere work.

stalks

pitch

the golden blood

of brooms.

iv.

mother in her rocker

her eyes

tire swings

her tongue

a cat’s tail.

v.

fourteen

my sister

martyrs herself

under the monkey

mad

in the stoplight.

vi.

in a church

hangs a coat

with a man

in it.

vii.

does not break loose

like they say

all hell.

visitation

the children

in a dry tub

their shed clothes

tight

at the necks

of dolls.

crash

of mother

in the kitchen

fathers

in different cars

aiming

for bottles.

god inhabits

a plaything

separates

each finger.

the oldest

puts one hand

on his head

and forces it down.

the youngest

comes up for water.

the middle

child

on his way home

from school

yesterday

saw the devil

prying horns

from a tree

and felt very much alone.

mother, rewrites

she will claim

channel 7 1973

had

both

god

& static.

that from a hole

in the ceiling

a man’s mouth

whispered

then

spit

at her

on the couch.

she will

put you

on the prayer chain. you will be watching tv

the phone will ring

it’s William

but you can call me Bill.

mother this is just.

mother this is just. a way

of

keeping.

you know

she stood there

with her military

man

and could feel

the baby

so okay

with dying.

a precise kingdom

the thing inside

a bullet my brother

made up. I shot you while you

slept. then clicked his thumb

down.

**

if you run away I will break

favorite

lines

you speak of war.

**

alone, loaded up with light. in that room

the bus drove by.

the baby’s head is orange the plastic

broken

arm of the most coveted

toy

also orange.

**

brother I understand

this city named

you. I ask the locals

a better word they hand me

license plates.

**

the bone car dead behind you.

the small

unique

body of your daughter

back in the states.

you crush it, into your side, it stays

with you, it’s a fragile

spear. badly made.

**

it stays with you, a child’s tooth in the pillow.

bite mark on a cloud. dream of exit

before entering the bar where the local argument

is more about

how far you ran

with a headless

doll.

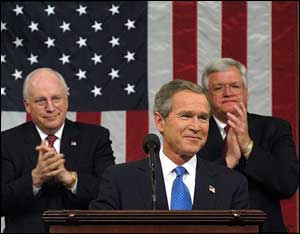

How did America go from a president elected after urging voters to forget about his religion to, 40 years later, a president who made religion central to his campaign, declaring Jesus as his “favorite philosopher”?

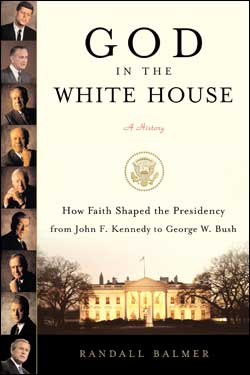

Randall Balmer, a professor of American religious history at Barnard College and editor-at-large for Christianity Today, tries to answer this question in his 12th book, God in the White House: A History: How Faith Shaped the Presidency from John F. Kennedy to George W. Bush.

Balmer, who describes himself as a left-leaning evangelical Christian — his last book was Thy Kingdom Come: How the Religious Right Distorts the Faith and Threatens America, talked with InTheFray about the role of religion in presidential politics, the “abortion myth” in the rise of the Religious Right, and why religion is best left “on the margins of society, not the councils of power.”

Interviewer: Jonathan Mandell

Interviewee: Randall Balmer

God in the White House ends before the 2008 presidential campaign begins. What role has religion played in this campaign, and how does it differ from previous presidential campaigns?

The most intriguing element of the 2008 presidential primaries was the attempt by Mitt Romney to become the Republican nominee. He’s not the first Mormon to run for the White House, of course. Joseph Smith, the founder of Mormonism, made a run in 1844, though it was cut short by his assassination at the Carthage jail. And Orrin Hatch, Republican senator from Utah, made a brief try in the 2000 campaign season. The most remarkable precedent, however, was Mitt Romney’s father, George, the governor of Michigan, who was the early favorite in the Republican primaries in 1968.

I happened to be living in Michigan at the time, and I have no recollection whatsoever that George Romney’s Mormonism was an issue in 1968. His candidacy eventually imploded when he professed to have been “brainwashed” about Vietnam. In the course of doing research for God in the White House, I looked back at the 1968 campaign to see if somehow I’d missed it, but it simply had not been an issue.

But 40 years later, it became clear — to everyone but Mitt Romney, it seems — that the former governor of Massachusetts would not be given a pass on his Mormon faith, unlike his father.

Why do you think there was such a difference in the reaction to George Romney’s and to Mitt Romney’s Mormonism?

What I call the “Kennedy paradigm” of voter indifference toward a candidate’s faith prevailed in American presidential politics from the 1960 campaign through the 1972 campaign. But then Nixon’s corruptions set the stage for Jimmy Carter’s out-of-nowhere run for the presidency in 1976.

I also think, frankly, that Mitt Romney played it all wrong. He went to the George Bush Library in College Station, Texas to give what reporters were calling his “JFK speech.” But Romney was handicapped in that the two central arguments that John Kennedy used in his 1960 speech to the Greater Houston Ministerial Association were unavailable to him. In that memorable address, Kennedy unequivocally affirmed his support for the separation of church and state, and he renounced all government support for religious schools. Because Romney was pandering after the votes of the Religious Right, however, whose leaders believe in neither of those foundational principles, Kennedy’s arguments wouldn’t play.

I think that a better model for Romney would have been Joe Lieberman, not JFK. When Al Gore named Lieberman to the ticket in 2000, he faced a flurry of questions about his Judaism. Was he Orthodox or merely observant? Why didn’t he campaign on the Sabbath? Unlike Romney, who grew testy whenever anyone asked him about his faith — “I’m not a theologian; I don’t speak for my church” — Lieberman faced those questions directly and without evasion.

What did you make of the surprising success of Mike Huckabee, a candidate whose day job had been as a Baptist preacher? How unprecedented was this?

I’ve tried to determine the last time an ordained minister made it this far in the primaries. It was, I believe, Jesse Jackson in 1984. Pat Robertson made a run at the Republican nomination in 1988, but he resigned his ordination just before announcing his candidacy.

But Jackson didn’t emphasize his religion, and Robertson didn’t have the electoral success that Huckabee had for at least part of the primary season. When is the last time we had such a successful candidate who connected the dots between his religion and his politics in such boldface?

The last time, I think, was Jimmy Carter. I make the case that Carter was the only president we’ve had in the last half century who actually sought to govern according to the principles he articulated in his campaign for the White House.

You also point to the irony that his presidency led, in a way, to the rise of what you call the Religious Right — the re-introduction of evangelicals into worldly affairs after more or less hibernating for 50 years after the Scopes evolution trial of the 1920s.

One of the great paradoxes of presidential politics over the last half century is that evangelical Christians, who helped propel Jimmy Carter to the presidency in 1976, turned dramatically against him four years later.

What became clear to me, as I was working through the archives at the Carter Center, is that Carter himself was utterly blindsided by the Religious Right in the run-up to the 1980 election. He didn’t see it coming. When he finally hired a religious-affairs liaison — a Baptist minister — it was really too late.

You document what you call the “abortion myth” in the birth of the Religious Right.

To hear the leaders of the Religious Right tell it now, they became politically active in direct response to the Supreme Court’s Roe v. Wade decision on abortion, which was handed down on January 22, 1973. According to this scenario, these hitherto apolitical ministers reluctantly entered the political fray out of their own moral outrage over the Roe decision. These leaders of the Religious Right even characterize themselves as the so-called “new abolitionists,” in an effort to equate their opposition to abortion to the opposition of antebellum evangelicals to the scourge of slavery.

The truth, however, is rather more complicated. The Southern Baptist Convention, hardly a bastion of liberalism, passed a resolution at its gathering in St. Louis in 1971, calling for the legalization of abortion — a resolution reaffirmed in 1974 and again in 1976. When the Roe decision was handed down, several evangelicals, including the redoubtable fundamentalist W. A. Criswell of First Baptist Church in Dallas, applauded the ruling as marking an appropriate distinction between personal morality and public policy.

I call this the “abortion myth” because abortion had little — almost nothing — to do with the emergence of the Religious Right. The Religious Right did indeed arise in response to a court decision, but it was not Roe v. Wade. It was a lower court ruling in 1971 called Green v. Connolly, which upheld the Internal Revenue Service [IRS] in its ruling that any organization that engaged in racial segregation or discrimination was not, by definition, a charitable organization, and therefore had no claim to tax-exempt status. In the ensuing years, the IRS sought to enforce that ruling, and acted against various private “segregation academies” (schools founded in response to the Brown vs. Board of Education Supreme Court decision of 1954 that ordered public schools desegregated). The IRS also targeted a fundamentalist school in Greenville, South Carolina, called Bob Jones University, and it was this action that triggered the evangelical activism that became known as the Religious Right. Only later, in preparation for the 1980 presidential election was abortion cobbled into the political agenda of the Religious Right.

Your book makes clear that evangelical, Baptist, fundamentalist, Christian Right, and Religious Right are not all synonyms, as they may appear to be to the outsider. Could you explain the distinctions?

By no means are all evangelicals part of the Religious Right. It’s probably fair to say that a plurality, perhaps even a majority, of evangelicals list toward the right. But even that is changing, especially among younger evangelicals, who are increasingly concerned about such issues as global warming, the war in Iraq, and this administration’s persistent, systematic use of torture. They care little about issues of sexual identity, and they’ve grown weary of what passes for debate over the abortion issue.

As for nomenclature, I prefer the term “Religious Right” to “Christian Right” or other variants. Frankly, as a Christian, I don’t find much that I would identify as “Christian” in the actions and agenda of the Religious Right.

Are Baptists by definition evangelicals?

Historically, it’s probably fair to say that all Baptists were evangelicals in that they believed in the centrality of religious conversion, the inspiration of the Bible, and the mandate of evangelism. Today, however, some Baptist groups are more theologically liberal and would probably resist — even resent — being called evangelical. Having said that, I would argue that the largest Baptist denomination — the Southern Baptist Convention — is thoroughly evangelical.

You say that the reason why abortion and homosexuality became the focus of the Religious Right is that they could no longer focus on divorce.

When the leaders of the Religious Right embraced Ronald Reagan — a divorced and remarried man — as their political savior in 1980, they dropped almost immediately their long-held objections to divorce. Not that they began advocating divorce; I’m not suggesting that at all. But I went through the pages of Christianity Today, the flagship magazine of evangelicalism, to chart the frequency of articles condemning divorce in the 1970s and again in the 1980s. I forget the numbers, but the denunciations of divorce in the pages of Christianity Today dropped virtually out of sight after 1980.

You seem to write mostly about evangelical Christians when discussing the interplay between religion and politics. Are they by far the largest factor in the heightened mix? Where, for example, do Catholics — who reportedly make up 24 percent of the U.S. population — figure in this interplay?

The leaders of the Religious Right have been very effective in cooperating with conservative Roman Catholics on political issues, especially abortion. This has led to some political successes, although I don’t think the Religious Right has much to show for its activism over the past several decades, aside from judicial appointments. One of the things that I find fascinating is the extent to which politically conservative evangelicals have relied on conservative Catholics for their political ideology and their ability to bring intellectual heft to the Religious Right. It strikes me as no accident that George W. Bush’s appointments to the Supreme Court have been conservative Roman Catholics. That suggests to me that the Religious Right itself simply doesn’t have a strong “bench” of ideologues, so they look to the Catholics.

The cooperation between conservative Catholics and politically conservative evangelicals, however, has had at least one happy effect: The level of suspicion between evangelicals and Catholics has dissipated considerably. When I was growing up as an evangelical, for example, my parents told me that I would be disowned if I married a Catholic. Those prejudices may not have disappeared, but they have abated considerably.

In God in the White House, you write: “My reading of American religious history suggests that religion always functions best from the margins of society, not in the councils of power.” What do you see as the major pros and cons to the heightened attention to religion in politics in the U.S. as a whole and, in particular, in presidential politics?

I personally have no objection to quizzing presidential candidates about their faith. The problem lies more with the voters than with the politicians, who, after all, merely parrot back to us what they think we want to hear. So if we ask candidates about their faith, let’s first of all listen to the answers. More important, let’s interrogate those claims.

Suppose, for example, that when George W. Bush declared that Jesus was his favorite philosopher on the eve of the 2000 Iowa precinct caucuses, someone had asked: “Governor Bush, Jesus, your favorite philosopher, calls on his followers to be peacemakers, to love their enemies, and to turn the other cheek. How will that affect your foreign policy, especially in the event of, say, an attack on the United States?”

Or: “Governor Bush, Jesus expressed concerned for the tiniest sparrow. Will that sentiment find any resonance in your environmental policies?”

I suspect that if we, the voters, began seriously to interrogate the faith claims and the religious rhetoric of our politicians, one of two things would happen. Either they would seek to live up to those claims — as no president over the last half century other than Jimmy Carter has done — or they would cease making empty statements that are utterly devoid of content.

During the Constitutional Convention of 1787, Charles Pinckney of South Carolina advocated the addition of the following phrase: “but no religious test shall ever be required as a qualification to any office or public trust under the authority of the U. States,” prompting a brief but intense examination of the role of faith in politics from the earliest days of American history. Those against the phrase believed that Enlightenment liberalism negated the need for such a test. Advocates of the phrase believed the requirement of a federal ban on religious tests would preserve the tests already practiced by the states at the time.

Fresh from their own contentious state conventions, the delegates sought to avoid the subject of religion in the Constitution. They trusted that the practice of religious freedom in general would prevent any one sect from dominating all others and casting undue influence over politics.

The honeymoon of religion-free politics was short-lived, however. Just three years later, a de facto religious test dominated the 1800 presidential election. Thomas Jefferson believed firmly in a private faith, between a man and his God. John Adams advocated that faith belonged in the public sphere, with the ultimate goal of preserving morality. Adams explained his loss of the presidency by reasoning that Jefferson’s camp framed the election in terms of religious liberty or religious orthodoxy; given those options, Adams, years later, didn’t fault the American people for choosing religious freedom over the risk of the establishment of a national faith.

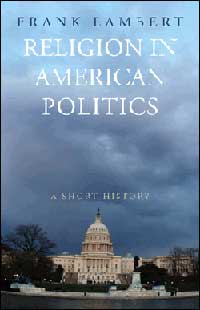

Now, more than 200 years later, much has been made of religion in this current election cycle. Despite the constitutional separation of church and state, the two have in fact had a long, convoluted, intertwined history, as explored by Frank Lambert in his new book, Religion in American Politics: A Short History. While no official faith-based litmus test has ever been established for those running for elected office, Lambert, a history professor at Purdue University, posits that the influence of religion is, and has been, both foreground and background in American politics.

In America’s early days, the Founding Fathers put their trust in the idea that religious pluralism would defend against any one sect or faith becoming too powerful. This was despite the fact that vying factions argued either that it was folly for the young nation not to acknowledge the work of providence in its creation, or, in order to avoid widespread religious conflict and oppression, that it was critical that no religion be nationally established. The resulting lack of federal — and later state — support mobilized religious groups to work within the political system to achieve their goals.

The role of religion in American life, and politics in particular, has resurfaced numerous times throughout American history. In his book, Lambert examines the roots, evolution, and developments of this relationship through the days of westward expansion, the rise of industrialism, the Gilded Age, post World War II, the rise of the conservative-leaning Moral Majority of the 1980s, and the dynamic between the Religious Right and the Religious Left as we approach the 2008 election.

Time and time again, the issue of faith has shaped and influenced American history. In the early 1800s, congressional approval of Sunday mail delivery was seen as a choice between the obligation of a Christian nation to keep the Sabbath holy and the federal government’s obligation to provide a national economy with the infrastructure necessary for growth. The Scopes trial of 1925 crystallized the conflict between science and religion, as John Scopes stood trial for violating the law that prohibited the teaching of Darwinism in public schools. Meanwhile, religious groups of the day resisted the growing influence of scientific thought on the basic tenets of faith — for example, the view of the Bible as a historical document instead of God’s literal word, or the use of technology in the form of radio with the growing influence of orators who celebrated their faith and motivated their followers.

In the 1960 election cycle, voters rejected an unofficial religious test in the Nixon/Kennedy race, merely requiring that their candidates reflect general Protestant heritage and values — a civil religion — allowing for the election of the Catholic Kennedy. Twenty years later, born-again Christian President Jimmy Carter, seen as a man of character and values, and who was elected in the wake of the turbulent Nixon administration, was repudiated by evangelical supporters after he failed to align his administration with their goals. This was another watershed moment at the crossroads of religion and politics that contributed to the dominance of Moral Majority in the American political landscape of the 1980s. It also contributed later to the election of George W. Bush, a candidate who, in effect, responded affirmatively to an unspoken religious test, an assurance to conservative Christians and evangelicals that his goals and theirs were aligned.

Lambert examines the centuries-long evolution of the relationship between politics and religion, and its ebb and flow in response to social, cultural, and economic concerns. His work shows that the arguments made by the Founding Fathers as a basis for their foregoing a religious litmus test, that religious conflict would jeopardize the “more perfect Union” that they’d worked so hard to attain, show an eerie presentiment. As the political right and left ratchet up their rhetoric in the run up to the 2008 presidential election, there is a divisive religious undercurrent that remains.

In 2007, the signs were clear that the unofficial religious test still existed as mainstream media reported on voters’ concern about Mitt Romney’s Mormon faith. He stated in a December 2007 speech at the George H.W. Bush Presidential Library that “Our Constitution was made for a moral and religious people.” And in early 2008, Barack Obama, who had been quoted in 2006 as saying that it is a “mistake when we fail to acknowledge the power of faith in the lives of the American people,” was forced to defend his membership at Trinity United Church after the pastor of the church was reported to have made racially divisive statements.

The eight major eras Lambert chooses to examine more closely in his book reflect times of great change and opportunity in America — economically, politically, and socially — which is expressed in both politics and religion. The book weakens slightly in the middle, but is buttressed by a very strong beginning and ending.

Perhaps Lambert’s most successful achievement with his book is the correction of the perception that this phenomenon is anything new, or that it will go away any time soon. The book is light on suggestions for a resolution; but Lambert’s framing of his discussions so firmly in American history seems to suggest that only by reigning in all sides, in keeping with the Founding Fathers’ original intentions, can the tide of increasing vitriol be stemmed.

We asked contributors and readers to answer this question, which refers to the U.S. Constitution ban on a “religious test” to hold public office in America. The question could be answered as narrowly focused or as generally as desired, touching on the interplay between religion and politics in American society — what’s good and what’s bad about it.

Here are their responses. Join in and add your comments and opinions. What do you think?

Larry Jaffe , writer and Poet Laureate for Youth for Human Rights

(Los Angeles, California)

From the United States Constitution, Article VI, section 3:

“The Senators and Representatives before mentioned, and the members of the several state legislatures, and all executive and judicial officers, both of the United States and of the several states, shall be bound by oath or affirmation, to support this Constitution; but no religious test shall ever be required as a qualification to any office or public trust under the United States.”

In my humble opinion, we have lost the meaning of religion, and those who “swear” by their faith believe more in dogma than the spirit. Thus, “religious test” would not even be an accurate statement given today’s standards. It is not religion we see mixed with politics, but dogma. It is not appreciation of God or spirit, but a belief system one must adhere to in order to belong to the “winning” side. Religion, in the truest sense of the word, is a set of beliefs concerning the cause, nature, and purpose of the universe, and often containing a moral code governing the conduct of human affairs. Politics of late, and perhaps always, certainly lacks moral code; simply witness the latest presidential primaries.

Furthermore, religious tolerance, perhaps one of the most important aspects of being religious, is all but abandoned. It is important to treat another’s religion as you wish yours to be treated. We have seen that when religious dogma mixes with politics, we lose all sense of religion.

Ryan Fuchs, mechanical engineer, blogger (Minneapolis, Minnesota)

The religious views (or lack thereof) should be no more relevant to their office than their sex or the color of their skin. The drafters of our Constitution understood this and bothered to state exactly that quite clearly. Many voters, however, are happy to be comforted with the knowledge that someone thinks as they do beyond the pertinent issues. In order to gain sway with this group, a candidate will advertise their religious beliefs. This has become the norm in elections of late. So much so that a growing number of people think the Constitution should be altered to make faith in a god necessary. I think that’s as silly as the desire to teach “creationism” in public schools. You’re free to have faith in whatever you choose. So am I. And so is anyone running for a public office.

John Amen , writer, musician, and founder and editor of The Pedestal Magazine (Charlotte, North Carolina)

Well, in theory politics and religion aren’t supposed to mix; i.e., a politician ought to be able to run a successful campaign regardless of his or her religious leanings. But we know that isn’t the case in America, at least currently. Bottom line, you’re not going to get elected to any significant office in America unless you espouse Christian principles. Clearly this is the case as far as getting the Republican vote but, in the end, I think it’s true with the Democratic vote, too. If you’re not a “Christian,” you’re fundamentally “the other,” regardless of all the PC talk, etc. This might change at some point. I mean, we’re looking at having a woman or African American in office, so that’s huge progress. Perhaps we’ll experience progress, too, in the relationship between politics and religion. But right now, if you espouse too loudly anything that departs from what’s considered essentially Christian, you’re probably not going to get very far.

Shawn Sturgeon, writer, author of Either/Ur (The River City Poetry Series) (Denver, Colorado)

There has always been an unofficial religious test for political candidates in the United States, since in the broadest terms, religion is concerned with the morals and values of a community. The question that challenges each generation of Americans is this: Who will write the test? We find the nature of the conflict over religion in American political life in two contradictory mottos engraved on the money we spend daily — “In God We Trust” and “E Pluribus Unum.” The first motto represents one way of deciding who writes the test: Let a single group with a sincere but narrow ideology determine the candidate who best represents “the good life” as they understand it. The second motto represents another approach: Respect differences of opinion and practice while achieving a consensus that “the best life” excludes no one. Personally, I favor the latter approach, but what does a poet know? Now I need to get back to chasing beaches and flowers.

Pris Campbell, writer , clinical psychologist (West Palm Beach, Florida)

If we’re talking theoretically, yes, of course they should. A candidate should be judged on his or her qualifications, alone. That’s not the way voters’ minds work, though, and sometimes with good reason. It’s only human nature to look at a candidate’s beliefs/religious associations, since we feel, at some level, those two things could play a role in political decisions. Take the flap with Obama’s minister, for example. When I saw the videos of him denigrating white people, calling us the U.S. of KKK, saying that 9/11 was a punishment … well, to know that this man was like family to Obama floored me. It also dramatically increased my leeriness about his potential presidency. A white minister could never be televised making racial statements and not damage a close political friend in the process. Obama has only said that his friend had the right to say what he thinks (which he does), but he’s not gone further, as of this writing, to say he disagrees adamantly with the anti-white statements.

The flap with Obama’s minister is even worse than when John Kennedy was running for office. The outcry was “Do we want the Pope to run our county?” I still remember that campaign. People were terrified over that issue. Now, if a Catholic ran, it would be a moot point. I wonder how a candidate who was close friends with a TV evangelist telling us he’s been called by God to collect money from little old ladies living on tiny SS checks would fare? Bottom line, beware of your bedfellows. Religious or not, they may kick you in the kneecaps when you least expect it.

David Paskey, graphic designer and songwriter (Chicago, Illinois)

I am not a fan of labels, so while I am reluctant to call myself a “Christian,” I would say that I aim to be a follower of Christ. My beliefs are not just an area of my life; I see them as something that runs through all of the parts of my life and the decisions I make. But I think it is important that a candidate realize that she/he would be serving the whole of the populace, those of many backgrounds and beliefs, including the belief in no God. So it is important to make choices that best serve the basic human rights and needs of the populace, while using one’s personal beliefs as a motivator to continually seek what is best for the public. I do not think it right to require a person to adhere to any belief in order to hold office. However, I feel it is human nature that people tend to elect a person who seems to hold their common interests and beliefs at heart, whether those beliefs be Christianity, Islam, Agnosticism, Scientific Inquiry, etc. Who the “right person for the job” is seems inextricably tied to the voters’ own beliefs. But once elected, it is important to remember that you serve the whole of society, not just the people who believe as you do or elected you.

Barton Smock, InTheFray contributor (Columbus, Ohio)

Is there a “religious test” in politics? One that can be passed, anyway? I don’t think so. Voters have their pencils, and boxes that mark a soul. And politicians sharpen those pencils accordingly. If a test exists, it is merely of a need to get the right students in the classroom. I don’t doubt that many in office hold personal, strong beliefs of moral content in regards to religion, and vice versa, but I am not one to believe that these personal beliefs are on display in full. They are parsed and directed. And when they are on display in full, when they are not personally exclusive, they are uncompromising and damaging. See the current administration. And, in a possible misquoting of a William Stafford poem, the Aztec design has God in a pea that is rolling out of the picture. We say god is everywhere, but how did he get out of the pea? What I believe has been given to me, mostly, by others. So, as humans, I think it is our responsibility to remain human. The internal is more external than we think. If one wants to name it god, or post it on the refrigerator like so many totems, so be it. God should be in the picture, so long as he remains in the pea.

Joel Lowenstein (Charlotte, North Carolina)

I believe strongly in the First Amendment’s separation of church and state. This separation is the fundamental difference between a theocracy and a democracy. The question of whether we are, as a people, to follow the dictates of conscience or those of organized religion can be a contentious one. We must only look at history to see the failures of governing from a religious pulpit. The puritans left England to escape religious persecution; at that time the government and the church were practically one and the same. The safeguards written into the First Amendment were put there to protect the citizenry from religious intolerance, to prevent religious prejudice and persecution. There should be no political religious test, lest we fall prey to religious zealotry or xenophobes and are all decreed heretics.

Joel Lowenstein is a military veteran who was conscripted into the service during the Viet Nam era; he was honorably discharged from the service in 1972. He resides with his wife and two daughters in Charlotte, North Carolina, where he currently is the owner and president of a for-hire maintenance repair, home improvement corporation.

“ReligionLink is produced by the Religion Newswriters Foundation, the educational arm of the Religion Newswriters Association (RNA). It is funded by a grant from the Pew Charitable Trusts. RNA is an independent, nonpartisan organization of journalists, who cover religion for the secular media.”

“The American Academy of Religion operates Religionsource, which is supported by Lilly Endowment Inc. and The Pew Charitable Trusts. Religionsource provides journalists with prompt referrals to scholars who can serve as sources on virtually any topic related to religion.”

The Roundtable on Religion & Social Welfare Policy

“Formed in January 2002 with a grant from The Pew Charitable Trusts to the Research Foundation of the State University of New York, the Roundtable on Religion and Social Welfare Policy was created: ‘To engage and inform government, religious and civic leaders about the role of faith-based organizations in our social welfare system by means of nonpartisan, evidence-based discussions on the potential and pitfalls of such involvement.’”

Pew Forum on Religion & Public Life

“The Pew Forum on Religion & Public Life, launched in 2001, seeks to promote a deeper understanding of issues at the intersection of religion and public affairs.”

“Religion & Politics,” The Pew Forum

“The United States has a long tradition of separating church from state, yet a powerful inclination to mix religion and politics. Throughout our nation’s history, great political and social movements — from abolition to women’s suffrage to civil rights to today’s struggles over abortion and gay marriage — have drawn upon religious institutions for moral authority, inspirational leadership and organizational muscle.”

“According to an August 2007 poll by the Pew Forum and the Pew Research Center for the People & the Press, the vast majority (69%) of Americans agree that it is important for a president to have strong religious beliefs. However, a sizable majority (63%) opposes churches endorsing candidates during election campaigns. Just 28% say churches should come out in favor of candidates, but that number has grown slightly since 2002 when only 22% held this opinion.”

“This year’s crop of presidential hopefuls has talked about where they go to church, how they interpret the Bible, what they pray for and other spiritual matters.

“But where do they stand on crucial religious freedom issues like ‘faith-based’ initiatives, ‘intelligent design’ and church-based politicking?”

A blog hosted by Utne magazine with a regular roundup of faith-based topics.

Thomas Jefferson’s letter to the Danbury Baptists, January 1, 1802

“Believing with you that religion is a matter which lies solely between Man & his God, that he owes account to none other for his faith or his worship, that the legitimate powers of government reach actions only, & not opinions, I contemplate with sovereign reverence that act of the whole American people which declared that their legislature should “make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof,” thus building a wall of separation between Church & State.”

One Vote Under God: The Role of Faith in the 2008 Presidential Campaign

“One Vote Under God attempts to provide a comprehensive, interactive portrait of the ways in which faith has been invoked in the race for the White House in 2008.”

“Who Would Jesus Vote For?” The Nation, March 24, 2008

“In a time when the much-ballyhooed evangelical political machine shows unmistakable signs of flying apart and scattering in uncertain directions, here was a momentary return to the old order.”

“Obama and the Bigots,” Nicholas D. Kristof, New York Times, March 9, 2008

“Yet the most monstrous bigotry in this election isn’t about either race or sex. It’s about religion.”

“Can Religion Lead to Peace?” Marshall Breger, Moment Magazine, October/November 2007

“Like the dog that didn’t bark, the absence of religious content speaks volumes about the assumptions that drive conventional diplomatic wisdom in Washington. Foreign policy professionals instinctively recoil at the notion that religion can or should play an important role in foreign policy. They see religion as a ‘private matter,’ according to Tom Farr, former director of the State Department’s office of international religious freedom, ‘properly beyond the bounds of policy analysis and action.’”

God-o-Meter, Beliefnet.com in partnership with Time Magazine

“The God-o-Meter (pronounced Gah-DOM-meter) scientifically measures factors such as rate of God-talk, effectiveness — saying God wants a capital gains tax cut doesn’t guarantee a high rating — and other top-secret criteria (Actually, the adjustment criteria are here). Click a candidate’s head to get his or her latest God-o-Meter reading and blog post.”

“Religion as a political weapon,” David Domke, USAToday, December 3, 2007

“Though the Founders sought to avoid the communion between politics and faith, presidents of the past three decades have thought, and acted, otherwise. Carter ran proudly as a Southern Baptist but honored the church-state line while in office. But beginning with Reagan, that distinct line began to fade.”

Mitt Romney in a speech at the George Bush Presidential Library, December 6, 2007

“There are some who would have a presidential candidate describe and explain his church’s distinctive doctrines. To do so would enable the very religious test the founders prohibited in the Constitution. No candidate should become the spokesman for his faith. For if he becomes president he will need the prayers of the people of all faiths.”

“Politicians Can’t Serve Two Masters,” Randall Balmer, WashingtonPost.com, February 22, 2008

“I see precious little evidence that any of the candidate’s declarations of faith — all of them claim to be Christians — have a direct impact on their policies.”

“Faith & Politics: After the Religious Right,” E.J. Dionne, Jr., Commonweal, February 15, 2008

“Notice what is happening here: the new politics of religion is not about driving religion out of the public square. It is about rethinking, again, religion’s public role. It is the latest corrective in our ongoing national debate over religious liberty, not a repudiation of religion’s social and political role.”

“Reclaiming God,” Mimi Hanaoka, InTheFray, June 25, 2005

“With 63 percent of church-going Americans voting Republican, it seems self-evident that the vocal and visible Christian right would enjoy a monopoly on political influence. Now Patrick Mrotek has decided to pit faith against faith and has founded what he hopes will be the voice of the Christian left: the Christian Alliance for Progress .”

“President Bush’s God,” Mimi Hanaoka, InTheFray, May 22, 2006

“‘I worked for two presidents who were men of faith, and they did not make their religious views part of American policy.’”

Eleanor Roosevelt on religion, InTheFray, November 30, 2006

“…the domination of education or of government by any one particular religious faith is never a happy arrangement for the people.”

1620: The Mayflower Compact

Religious radicals seeking to “purify” the Church of England are run out of the country, and cross the Atlantic on a ship called the Mayflower, settling in what is now Massachusetts. Upon landing, the so-called Puritans draft the Mayflower Compact, considered the first written constitution in North America, in which they state their journey had been “undertaken for the glory of God, and advancement of the Christian faith,” and they were now forming a “civil body politic.”

1636: Roger Williams founds Providence

The Massachusetts Bay Colony banishes Roger Williams, a radical clergyman who preaches freedom of religion and the separation of church and state. Williams and a small group of followers buy land from the Indians and establish Providence, Rhode Island. A beacon of religious liberty in early America, Rhode Island is at one time the only colony not to have anti-Quaker laws on its books.

1681: William Penn founds Pennsylvania

William Penn, a Quaker convert from a wealthy English family, obtains a colonial charter and founds Pennsylvania on land purchased from Indians. The colony becomes home not only to the much-persecuted Quaker minority — subject to exile and execution elsewhere for their anti-authoritarian and nonviolent views — but also to a wide range of other religious groups unwelcome in other colonies. Penn drafts a colonial constitution far ahead of its time, the Frame of Government, which codifies principles of religious liberty and the balancing of power across different branches of government.

1779: Virgina Statute for Religious Freedom

Three years after penning the Declaration of Independence, Thomas Jefferson drafts the Virginia Statute for Religious Freedom. The statute forbids the government from dictating religious beliefs, arguing that “Almighty God hath created the mind free” and “civil rights have no dependence on our religious opinions, any more than our opinions in physics or geometry.” The Virginia General Assembly takes seven years to enact the statute, but Jefferson cites it in his epitaph as one of his three greatest achievements.

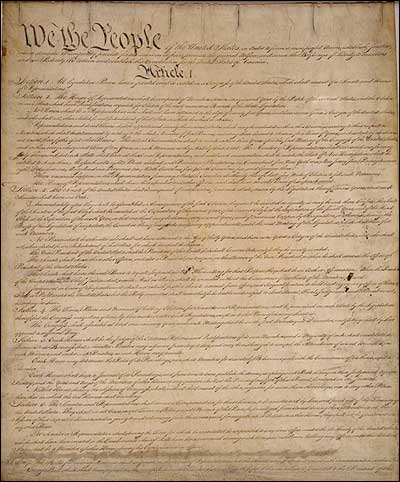

1787: Constitution

The Founding Fathers complete the Constitution, which states in Article Six that “no religious test shall ever be required as a qualification to any office or public trust under the United States.” Article Six also allows public officials to affirm, rather than swear, their support of the Constitution, a passage aimed at accommodating the Quaker minority, who were forbidden by their beliefs to swear oaths.

1791: First Amendment

Congress ratifies the Bill of Rights, whose First Amendment declares that “Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof.” These 16 words, the so-called establishment clause and free exercise clause, become the bedrock of constitutional law concerning the separation of church and state and the freedom of worship.

1797: Treaty of Tripoli

The U.S. Senate ratifies a treaty with Tripoli aimed at stopping Barbary pirates from terrorizing American shipping. The treaty declares that “the Government of the United States of America is not, in any sense, founded on the Christian religion.”

1802: “Separation of church and state”

Thomas Jefferson first used the phrase “building a wall of separation between church and state” to describe the First Amendment in a letter to the Danbury Baptist Association.

1827: Ezra Stiles Ely, Christian crusader

Presbyterian minister Ezra Stiles Ely preaches “The Duty of Christian Freemen to Elect Christian Rulers,” a sermon calling for the election of candidates who “know and believe the doctrines of our holy religion.” His movement amounts to a 19th-century version of the Christian Coalition, except that the early Christian political agenda focuses not on abortion or homosexuality, but on the evils of Sunday mail delivery.

1833: Last established church

The Commonwealth of Massachusetts officially rescinds support of an established church. It is the last state to do so. (At the time of the Revolution, most states had an official religion.)

1920: Prohibition

Decades of agitation by religiously inspired temperance activists culminates in the 18th Amendment, which bans the sale, manufacture, and transport of alcohol. Support for Prohibition is strongest among certain Protestant denominations, and the teetotaler cause brings together diverse constituencies, including the Women’s Christian Temperance Union, African American labor activists, and the Ku Klux Klan. Thirteen years later — after speakeasies mushroom throughout the country and illegal booze sales make gangsters rich — the amendment is repealed.

1925: The Scopes trial

John Scopes, a Tennessee high school teacher, violates a state law that bans teaching that “man has descended from a lower order of animals.” His trial unleashes a titanic struggle between supporters of creationism and evolution, who find their paladins in famed attorneys Clarence Darrow (for the defense) and William Jennings Bryan (for the prosecution). While trained chimpanzees parade outside the courthouse, inside the proceedings soon descend into a rambling discussion of what in the Bible is factual. Scopes loses and is levied a $100 fine, but the losers in the court of public opinion are Christian evangelicals, savaged by the press as “yokels” and “morons.”

1928: Catholic runs for president

Al Smith, the Democratic governor of New York, becomes the first Roman Catholic to become a major party’s nominee for president. Facing allegations that he would be a pawn of the Pope, Smith declares his belief “in the absolute separation of church and state.” Smith’s candidacy is greeted with great hostility, including Ku Klux Klan cross-burnings, and Republican Herbert Hoover trounces Smith on Election Day.

1947: Court endorses “Wall of Separation”

In Everson v. Board of Education, the Supreme Court rules 5-4 that government funding to bring students to and from their parochial schools does not violate the First Amendment’s establishment clause. But this decision also said the Founders intended a “wall of separation” between church and state. “Neither a state nor the Federal Government can set up a church. Neither can pass laws which aid one religion, aid all religions or prefer one religion to another.”

1954: “Under God”

Congress adds the words “under God” to the Pledge of Allegiance.

1956: “In God We Trust”

A federal law establishes “In God We Trust” as the official motto of the United States. It appears on U.S. currency.

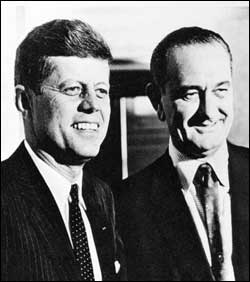

1960: Catholic wins presidency

John F. Kennedy, a Catholic, faces Richard Nixon in a closely fought presidential race. In an effort to defuse anti-Catholic sentiment, Kennedy gives a speech before a group of Protestant ministers in Houston, Texas, in which he states: “I believe in an America where the separation of church and state is absolute, where no Catholic prelate would tell the president (should he be Catholic) how to act, and no Protestant minister would tell his parishioners for whom to vote.” Two months later, Kennedy wins by a mere 0.1 percent margin in the popular vote.

1962: Public school prayer banned

In Eagle v. Vitale, the U.S. Supreme Court prohibited prayer in the public schools as a way to prevent “the indirect coercive pressure” that occurs “when the power, prestige and financial support of government is placed behind a particular religious belief.”

1976: Jimmy Carter, evangelical president

Jimmy Carter, a born-again Christian, is elected president of the United States, bringing evangelical faith out of the political wilderness. In a Playboy interview published weeks before his election victory, Carter admits to having looked on women with “lust” and having committed adultery in his “heart.”

1979: Moral Majority

Televangelist Jerry Falwell founds Moral Majority, a conservative Christian political organization that fervently opposes abortion, gay rights, the Equal Rights Amendment, and arms talks with the Soviet Union. With a membership in the millions at its peak, Moral Majority dominates an ascendant Republican Party throughout the 1980s, transforming the Religious Right into the establishment voice of American evangelicism and a potent force in national politics.

1987: Religious expression permitted in public places

The Supreme Court throws out a ban by the Los Angeles airport on leafleting by members of Jews for Jesus. This is the first of several “free speech” rulings over the next two decades that allow religious expression in public or even government settings, as long as it is initiated by private individuals or groups, rather than government officials. The Court ruled, for example, that a Christian student club in an Omaha public high school could meet after class.

2003: George Bush, “compassionate conservative”

President George W. Bush, a self-identified “compassionate conservative” strongly favored by evangelical Christian voters, says that God told him to invade Afghanistan and Iraq. Four months after the U.S.-led invasion of Iraq, Bush announces to a Palestinian delegation that the Almighty spoke to him with the words “George, go and fight these terrorists in Afghanistan” and “George, go and end the tyranny in Iraq.”

{mosimage}

Victor Tan Chen Victor Tan Chen is In The Fray's editor in chief and the author of Cut Loose: Jobless and Hopeless in an Unfair Economy. Site: victortanchen.com | Facebook | Twitter: @victortanchen

Democratic presidential candidate John F. Kennedy gave the following address to the Greater Houston Ministerial Association on September 12, 1960, at the Rice Hotel in Houston, Texas.

Reverend Meza, Reverend Reck, I’m grateful for your generous invitation to state my views.

While the so-called religious issue is necessarily and properly the chief topic here tonight, I want to emphasize from the outset that I believe that we have far more critical issues in the 1960 campaign; the spread of Communist influence, until it now festers only 90 miles from the coast of Florida — the humiliating treatment of our president and vice president by those who no longer respect our power — the hungry children I saw in West Virginia, the old people who cannot pay their doctors bills, the families forced to give up their farms — an America with too many slums, with too few schools, and too late to the moon and outer space. These are the real issues which should decide this campaign. And they are not religious issues — for war and hunger and ignorance and despair know no religious barrier.

But because I am a Catholic, and no Catholic has ever been elected president, the real issues in this campaign have been obscured — perhaps deliberately, in some quarters less responsible than this. So it is apparently necessary for me to state once again — not what kind of church I believe in, for that should be important only to me — but what kind of America I believe in.

I believe in an America where the separation of church and state is absolute; where no Catholic prelate would tell the president — should he be Catholic — how to act, and no Protestant minister would tell his parishioners for whom to vote; where no church or church school is granted any public funds or political preference, and where no man is denied public office merely because his religion differs from the President who might appoint him, or the people who might elect him.

I believe in an America that is officially neither Catholic, Protestant, nor Jewish; where no public official either requests or accept instructions on public policy from the Pope, the National Council of Churches, or any other ecclesiastical source; where no religious body seeks to impose its will directly or indirectly upon the general populace or the public acts of its officials, and where religious liberty is so indivisible that an act against one church is treated as an act against all.

For while this year it may be a Catholic against whom the finger of suspicion is pointed, in other years it has been — and may someday be again — a Jew, or a Quaker, or a Unitarian, or a Baptist. It was Virginia’s harassment of Baptist preachers, for example, that led to Jefferson’s statute of religious freedom. Today, I may be the victim, but tomorrow it may be you — until the whole fabric of our harmonious society is ripped apart at a time of great national peril.

Finally, I believe in an America where religious intolerance will someday end, where all men and all churches are treated as equals, where every man has the same right to attend or not to attend the church of his choice, where there is no Catholic vote, no anti-Catholic vote, no bloc voting of any kind, and where Catholics, Protestants, and Jews, at both the lay and the pastoral levels, will refrain from those attitudes of disdain and division which have so often marred their works in the past, and promote instead the American ideal of brotherhood.

That is the kind of America in which I believe. And it represents the kind of presidency in which I believe, a great office that must be neither humbled by making it the instrument of any religious group nor tarnished by arbitrarily withholding it — its occupancy from the members of any one religious group. I believe in a president whose views on religion are his own private affair, neither imposed upon him by the nation, nor imposed by the nation upon him as a condition to holding that office.

I would not look with favor upon a president working to subvert the First Amendment’s guarantees of religious liberty; nor would our system of checks and balances permit him to do so. And neither do I look with favor upon those who would work to subvert Article VI of the Constitution by requiring a religious test, even by indirection. For if they disagree with that safeguard, they should be openly working to repeal it.

I want a chief executive whose public acts are responsible to all and obligated to none, who can attend any ceremony, service, or dinner his office may appropriately require of him to fulfill; and whose fulfillment of his presidential office is not limited or conditioned by any religious oath, ritual, or obligation.

This is the kind of America I believe in — and this is the kind of America I fought for in the South Pacific, and the kind my brother died for in Europe. No one suggested then that we might have a divided loyalty, that we did not believe in liberty, or that we belonged to a disloyal group that threatened — I quote — "the freedoms for which our forefathers died."

And in fact this is the kind of America for which our forefathers did die when they fled here to escape religious test oaths that denied office to members of less favored churches — when they fought for the Constitution, the Bill of Rights, the Virginia Statute of Religious Freedom — and when they fought at the shrine I visited today, the Alamo. For side by side with Bowie and Crockett died Fuentes, and McCafferty, and Bailey, and Badillo, and Carey — but no one knows whether they were Catholics or not. For there was no religious test there.

I ask you tonight to follow in that tradition — to judge me on the basis of 14 years in the Congress, on my declared stands against an ambassador to the Vatican, against unconstitutional aid to parochial schools, and against any boycott of the public schools — which I attended myself. And instead of doing this, do not judge me on the basis of these pamphlets and publications we all have seen that carefully select quotations out of context from the statements of Catholic church leaders, usually in other countries, frequently in other centuries, and rarely relevant to any situation here. And always omitting, of course, the statement of the American Bishops in 1948 which strongly endorsed church-state separation, and which more nearly reflects the views of almost every American Catholic.

I do not consider these other quotations binding upon my public acts. Why should you?

But let me say, with respect to other countries, that I am wholly opposed to the State being used by any religious group, Catholic or Protestant, to compel, prohibit, or prosecute the free exercise of any other religion. And that goes for any persecution, at any time, by anyone, in any country. And I hope that you and I condemn with equal fervor those nations which deny their presidency to Protestants, and those which deny it to Catholics. And rather than cite the misdeeds of those who differ, I would also cite the record of the Catholic Church in such nations as France and Ireland, and the independence of such statesmen as De Gaulle and Adenauer.

But let me stress again that these are my views.

For contrary to common newspaper usage, I am not the Catholic candidate for president.

I am the Democratic Party’s candidate for president who happens also to be a Catholic.

I do not speak for my church on public matters; and the church does not speak for me. Whatever issue may come before me as president, if I should be elected, on birth control, divorce, censorship, gambling, or any other subject, I will make my decision in accordance with these views — in accordance with what my conscience tells me to be in the national interest, and without regard to outside religious pressure or dictates. And no power or threat of punishment could cause me to decide otherwise.

But if the time should ever come — and I do not concede any conflict to be remotely possible — when my office would require me to either violate my conscience or violate the national interest, then I would resign the office; and I hope any conscientious public servant would do likewise.

But I do not intend to apologize for these views to my critics of either Catholic or Protestant faith; nor do I intend to disavow either my views or my church in order to win this election.

If I should lose on the real issues, I shall return to my seat in the Senate, satisfied that I’d tried my best and was fairly judged.

But if this election is decided on the basis that 40 million Americans lost their chance of being president on the day they were baptized, then it is the whole nation that will be the loser, in the eyes of Catholics and non-Catholics around the world, in the eyes of history, and in the eyes of our own people.

But if, on the other hand, I should win this election, then I shall devote every effort of mind and spirit to fulfilling the oath of the presidency — practically identical, I might add, with the oath I have taken for 14 years in the Congress. For without reservation, I can, "solemnly swear that I will faithfully execute the office of president of the United States, and will to the best of my ability preserve, protect, and defend the Constitution — so help me God.

In this special edition of InTheFray, we focus on the interplay between religion and politics, especially during the singular and sometimes downright peculiar events of Campaign 2008, but we also go beyond U.S. presidential politics.

The complete line-up is to your right. Some stories offer a history of church/state issues in the United States. Others explain the consequences of recent developments, such as the look at the unhappy track record of President George W. Bush’s faith-based initiatives in Spreading the faith — and the funds. Some of this month’s articles report on conflicts between religion and politics abroad in places like Afghanistan. Others look inward, such as ITF senior editor Anja Tranovich’s interview with gay evangelical Rev. Mel White and Dr. Farnad Darnell’s personal essay on being Muslim/Mormon.

The question that inspired this edition — “Is there a ‘religious test’ in politics?” — was addressed two centuries ago in the U.S. Constitution, which specifically bans such a test “as a qualification to any office or public trust under the United States.” But in a broader sense, Americans have been struggling all along with this question in many ways. (See ITF Executive Director Victor Tan Chen’s time line highlighting more than 300 years of battles between "church and state")

Has religious conviction become a de facto requirement for presidential candidates in the half-century since the election of John F. Kennedy as the nation’s first (and so far only) Catholic president?

“I believe in an America where religious intolerance will someday end,” Kennedy said in his famous speech on religion in 1960, “… where every man has the same right to attend or not to attend the church of his choice, where there is no Catholic vote, no anti-Catholic vote, no bloc voting of any kind …”

Kennedy delivered that speech out of fear that his religion would deter many Americans from voting for him. In 2008, another presidential candidate, Mitt Romney, delivered a speech about religion and politics that consciously evoked the JFK address. Like Kennedy, Romney feared that Americans would not vote for him because of his religion, which in Romney’s case is Mormon. But some critics suggested the core of Romney’s argument was the exact opposite of Kennedy’s — intolerance of the irreligious rather than religious tolerance. “Freedom requires religion,” Romney said, “just as religion requires freedom.” (See more on Romney — including a fascinating contrast with his father George — in our interview with Randall Balmer, author of God In The White House.)

But the speech that has earned more comparisons with Kennedy’s during this campaign season was delivered by Barack Obama. Though Obama’s speech focused on race, it was brought about by religion: The speech was Obama’s response to attacks on his former pastor’s sermons. (Mark Winston Griffith comments on Obama’s speech in the context of politics and the black church in “The black church arrives on America’s doorstep.”)

For all this attention, Campaign 2008 does not seem to have clarified the issue of the role of religion in politics — or that of politics in religion.

“This political season has only heightened the confusion over the future of religion in the nation’s culture and politics,” Walter Russell Mead wrote in the March 2008 edition of the Atlantic Monthly, one of several publications to devote recent editions to the subject of religion.

Now InTheFray enters … into the fray. And so can you — add your answer to our round-up of views on whether there is a religious test in politics. Then take OUR religious test in politics, our quiz, and see if you know which 2008 presidential candidate said, “When discussing faith and politics, we should honor the ‘candid’ in candidate — I have much more respect for an honest atheist than a disingenuous believer.”

The answer — along with much in this edition — may surprise you.

Jonathan Mandell

Guest Editor

New York

According to the media, one of the latest green movements is happening in churches, synagogues, and mosques around the country. Several news organizations have already done stories about people from different faiths who all have the same goal of saving the environment.

The Weather Channel’s "Forecast Earth" profiles Baptist pastor and environmental advocate Dr. Gerald Durely, who was inspired by the environmental film The Great Warming. Dr. Durely says in the piece: "As one who believes that the Earth is the Lord’s and the fullness thereof, is that we have an obligation to ensure that what God has created, we keep together." The pastor has taken his environmental message and movement to his congregation because he says it will "make a difference for my children, my grandchildren, and generations to come when we begin to conserve and do what it is on this Earth that is so important."

ABC News looked into a North Carolina church that for the second year in a row is having a so-called "carbon fast" for Lent:

"Lent is a traditional time when we talk about reducing," said the United Church’s pastor, Richard Edens.

Lent is the 40-day period in which Christians fast and atone to prepare for Easter. This year the congregation has weekly themes; for example, one week they save water, another week they eat only locally-grown produce. And they are part of a growing international movement of carbon-fasters.

New Jersey Jewish News reports on a Jewish environmental organization’s call to synagogues to become more environmentally friendly by changing their old incandescent lightbulbs to energy-efficient ones: