Usually when one leaves a city for another, sheds a life and a skin for another, one turns one’s attention to what one must take along, rather than understanding what one must not leave behind. Father and I came to this city quietly, naked to the bone, to the recesses of our souls, though we didn’t know it. The aircraft that carried us landed lightly upon a long dark runway, and stopped. We were empty, vessels within a vessel. As we disembarked, set our feet firmly upon the dusty soil of this city, I remember thinking: This city is strange. I don’t belong here. I was seven at the time, and, without a doubt, was given to reason with that characteristically complex though effortless ease — the city was unfamiliar, strange, and I thought each step of mine an intrusion.

I now believe there were several reasons I felt the way I did. New Delhi summers are hot, and we arrived in the middle of June from wherever it was that we came. I was a child of winter, and in nail-biting cold, felt alive. I loved to resist winter’s icy offensive, its assault upon my being. I’d fight the cold because I could and because it made me feel brave, understood, even relevant. But now, the summer wind that accosted us as we hurried away from the craft was this strange city’s restraint, its displeasure; the harsh gust expected resignation, not a fight. New Delhi didn’t want us. We were flayed, the sun glared contemptuously and cracked open giant eggs of sweat upon our heads. I felt unwelcome, wanted to return to the craft, but Father gently pushed me into the departure terminal, mopping his forehead with a small, insufficient handkerchief. “On with you,” he said, “Go on, go on.”

On we went, till we stood before a conveyor belt that slowly whirred past while a bunch of us stood in a huddle, waiting. Father, too, at the time, contributed to my (our) situation. “On with you,” he’d said, while he reeked of that alcohol that so reminded me of wherever it was from which we came. Every inch of his body, more correctly his being, seemed to be absent, left behind at the place which was the very source of us. Our presence at that airport seemed to be so steeped in absence that we must’ve been invisible — someone lunged for their luggage, and I was thrown aside. Father didn’t notice.

“Why do people rush? It’s not like the luggage is going anywhere,” I said, mildly bruised.

Father continued to stare at the belt, through the belt, at something distinct and imperceptible. I repeated myself, and he finally looked at me, through me, and spoke.

“One place to the next, that’s the way it is.”

As the wait prolonged (there was a problem with one of the luggage transportation carts), I thought Father might turn into stone. He stood so very, very still, his glance unwavering, like a statue erected in fond memory of himself — my father who once was, and now, strangely, wasn’t.

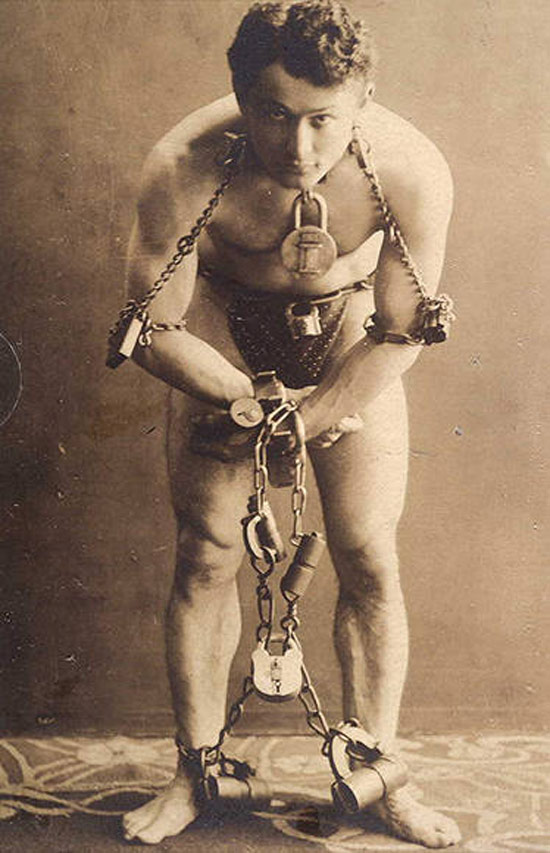

I gave in, as I often did, to reminiscing. I felt there was a library where memories went and were classified, and when one summoned, an appropriate one was sent along. Perhaps a stern librarian sat behind some giant wooden desk trembling beneath piles of memory retrieval applications. As luck would have it, that particular day, standing by the conveyor belt, I was not fortunate (the librarian must’ve been overworked). In a jolt, a flash, I was back where I came from, back on the streets of a lost city that was cold and lightless, my home. I was walking back from school, whistling to myself as it were, and upon turning a corner found myself surrounded by a horde of hooligans.

“Take off your clothes,” one of them said. He was large and filthy, looked singularly mad.

“Why?” I asked. “It is cold.”

“We’re feeling cold too,” he sang, and smiling, punched me in the face. I fell to the ground; my nose broke upon the pavement. A narrow stream of blood found its way down my face, and soon, a patch of ice on the street turned a pinkish red. No one moved for a few moments. It was as if we were all waiting to measure how much I’d bleed, how much blood, how much warmth, I had in me to lose.

Then I rose. “All right,” I said, removing my cap. As I peeled off my clothes, the hooligans claimed them and scattered, shouting, hooting, even whistling the tune I’d been whistling a few moments past.

I sat down on the bloody ice. I was naked and much too cold to move. Too cold even to cry.

The memory passed, and I found I was breathing harder. I turned my attention, once again, to the conveyor belt as it whirred and chugged on by. I hadn’t cried since that day, as though the cold of that nightmarish nakedness had then and for all time thereafter frozen the pools from where tears drop. Had my blood been turned to ice?

“I like the cold,” I told Father. “Delhi is too hot.”

He looked at me (through me) once again.

“Don’t worry, beta,” he said. “Delhi has its winter months too, around four in a year.”

I looked away. Maybe adults didn’t understand anything. No, they didn’t. Who was to decide who understood what? I was troubled by this question, confused, afraid to attempt to understand anything for I might misunderstand. That day was instilled in me a fear of comprehension.

“You’re seven,” said Father, when I spoke to him of this fear.

Our luggage arrived and we lunged for it with controlled hurry.

Soon we were in a cab (a black and yellow taxi), speeding away from the airport. Father sat beside me in the backseat, and stared out of the window as the city underwent an unending metamorphosis occasioned by our passage. I took to appraising him and I am now thankful for that decision — the vision of my father that day as he sat and surveyed this city is the memory of him I carry most distinctly, most clearly, even today. His shoulders were hunched, his handsome face only just beginning to show the signs of weariness. His large brown eyes were concealed behind thick, horn-rimmed spectacles, and his wide intelligent wrinkled forehead was lined with sweat. It was as if he was a glacier, beginning to melt, just then — a slow meltdown of age and heat and disorientation, and with each successive kilometer of our descent into this new world, he seemed to bite his lip harder, though he was never going to cry. Past him, I saw through the window odd bungalows and multiplexes and dust rising in spirals upon hordes of people. At red lights, beggars came and beat their fists, clanged their bangles, blessed and cursed us.

“Where are we going?” I asked him, desperate for some distinct emotion, as the biting of the lip I didn’t understand.

“To our new home.”

“Is it big?” Our earlier apartment had been big. It had grown bigger once my mother died.

“It’s big enough, yes.”

Settling in was not difficult — we barely had any luggage. It was true that the apartment was big enough, but it would be truer to say that our existences were unquestionably small, compact. The apartment was on the second floor of someone’s home, and had a bedroom with an attached bathroom, plus a drawing-dining-kitchen and no balcony. It took us about an hour to empty our suitcases.

Then, we slept, and in that sleeping waking dream, three years passed: I found myself enrolled at a school and found that I had friends. I saw myself smiling when I looked at my reflection, and soon, I began to find that summer was an added joy, and so was monsoon, so was spring, so was autumn. Soon I forgot that I ever was born in another city, that I ever had a mother. I forgot what she looked like, whether she smoked and drank the same alcohol as Father, whether she smelled nice. I found that I had cousins and aunts and uncles here, I felt as though I’d always lived here. I was wrapped and swept away in a tide of wanting to belong and then actually belonging and I unearthed, in some illusory, childish sense, a sort of happiness. All this while, Father walked beside me, behind me, in front of me, always a shadow that stretched around me, now grew, now collapsed toward me. When the thought of his loneliness hit home, I stopped to look at him. He was still the man he was in the black and yellow taxi, but further away from me, veiled in a darkness that was perhaps my happiness. But then I thought: Can one ever shed light upon a shadow?

The day after my 10th birthday, he moved me into my aunt’s home, and then disappeared.

I never saw him again.

Till this day, more than a few decades after the events I have just described, people speak to me of desertion, abandonment — a big word, an unforgivable act. I am asked: “Did you feel abandoned at the time?” I tire of telling people that it doesn’t matter what I felt at the time, for my feeling at the time cannot qualify his act — he left when I was 10. The act was neither wrong nor right, couldn’t be either. It was a fact — he left when I was 10, when I grew comfortable in my own shoes, when I forged a bond with this city. He did what he thought was best, and the act was neither right nor wrong. He couldn’t have known whether it would be either, because a man, at the end of what he supposes is his life, at the time of crisis, if he is moral, does what he thinks is best.

I like to think he didn’t abandon me, but abandoned instead a memory of another land, another time, which instead was his imprisonment — the memory of his wife, my mother, our home. I like to think he abandoned his imprisonment.

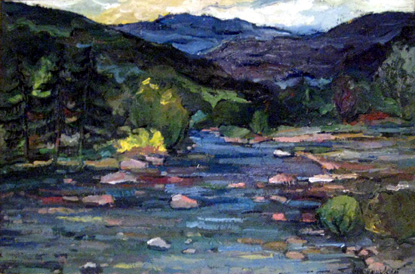

I like to think he returned to the part of his self that he left behind. I like to think he returned to that memory, to live in it as if it were not yet a memory but the actual content, the substance of his reminiscing. I like to think he now lives once again in the lost city that we so hurriedly left, no longer a prisoner of its memory, but a free man; he is at the beginning of something, thinking of me (as I am of him at the moment), snuggled in a blanket, warm in the cold, his glasses patient upon the bridge of his nose, his eyes alert, his hair grey, and his forehead less creased.

He’s reading a newspaper.

He’s home.

Ashish Mehta

Dear Reader,

In The Fray is a nonprofit staffed by volunteers. If you liked this piece, could you

please donate $10? If you want to help, you can also: