My mother was one of those unforgettable people. She was a great musician, composer, friend, and catalyst. She did not, however, have the same passions for the role of being a mother. She knew and felt guilty about this fact in her later years. My picture of her is not the same picture most people carry in their memories. For them, she was a friend, a composer, a drinking buddy, and was fun to be around. Her love for others was not far from the unconditional love I so deeply craved as a child.

My mother was one of those unforgettable people. She was a great musician, composer, friend, and catalyst. She did not, however, have the same passions for the role of being a mother. She knew and felt guilty about this fact in her later years. My picture of her is not the same picture most people carry in their memories. For them, she was a friend, a composer, a drinking buddy, and was fun to be around. Her love for others was not far from the unconditional love I so deeply craved as a child.

When she died, I decided to make new memories based on other people’s impressions of her. I am doing this in two ways: I am making a book of memories in a biography form, and I am making a day-to-day installation of death being part of my everyday life. In order for you to understand the process and the reason for the Ladybug’s journey, I will share with you something you might either find disturbing or beautiful. My aim is to make something beautiful from something ugly; my responsibility of creation is like this. I feel the pain; I transform the pain into joy. I experience death; I transform death into life. Grief is an evolution of loss. By transforming loss into gain, I can heal the wounds from the past.

My mother suffered from a disease, a disease that began when she was a child. It is called a severe, delusional sense of guilt. It started when her younger brother died in a car accident at the age of seven. She somehow got it into her head that she had something to do with his death; she didn’t lend him her yellow boots before he went off on his bike. During that time, no one talked about grief or loss. People just bottled it up and carried on. This guilt became larger than life and too much to cope with, and when she had her first taste of liquor to ease the disease, she was struck by another disease called alcoholism. The combination of these two diseases is usually lethal. And so, it was her fate to drink her talents, her voice, her music, and her life away in a haze of dysfunctional behavior, primarily toward herself. My mother lived in Denmark for many years, a self-made expatriate outlaw from her native island, Iceland.

She had one especially beautiful gift few people possess: She had the same respect for everyone, no matter if a person was a vagrant lady or the president. It was not unusual to have a person of the elite pay my mother a visit at the same time as a person from the streets of Reykjavik was using her sewing machine. She showed the same interest in people close to her as to the people she barely knew. Today, I see this as an almost enlightened state of being.

Like so many true artists, despite all her faults, she was greater than life. During her last years on this planet, she lost the connection with her creative muse. She withdrew further into her disease and self-destructive patterns. She told no one how ill she was as she dealt with lung cancer on her own in another country: no drugs, no operations, no hospitals. She was doing this death battle as was done in the old days: She knew her time on this planet was coming to an end, and she didn’t fight it. She didn’t want to change anything.

Like so many true artists, despite all her faults, she was greater than life. During her last years on this planet, she lost the connection with her creative muse. She withdrew further into her disease and self-destructive patterns. She told no one how ill she was as she dealt with lung cancer on her own in another country: no drugs, no operations, no hospitals. She was doing this death battle as was done in the old days: She knew her time on this planet was coming to an end, and she didn’t fight it. She didn’t want to change anything.

No one knew she was coughing up blood until she finally fell down bleeding on the floor in her local grocery shop, died, and was revived. Her fall was great, but greater still was her ability to make no fuss over life and death. She stayed for one day at the hospital, and she spent that day calming family and friends, telling us not to worry. She believed she would be home the following day. I could hear that her voice was frail. I managed to convince her that it was a good idea that my brother and I fly to Denmark to visit with her at the hospital. She sounded ill, yet she had not lost her pitch-black humor. The day before, she lost one-third of her blood on the floor in the shop. She never did anything halfway.

Early next morning, as my brother and I were boarding the plane for Denmark to stay with her at her deathbed, we got a call; our mother had passed away in her sleep during the night. It was the most difficult journey I have ever taken. To hold the grief within — a tsunami of emotion — because it is not socially acceptable to lose it in public spaces like planes, my brother and I made sure not to look at each other. We just breathed shallowly to keep it all in. And, in perfect harmony with the dramatic flair of my everyday life, the low-budget plane was full of dentists, including my own dentist, who was getting drunker as each moment passed. The only thing missing was for them to start singing one of my mother’s songs.

When the long journey was finally over, we arrived at the hospital where my mother had taken her last breath. In a surreal way, we had to run around this big and impersonal hospital to find her body and the rest of her belongings. Since it is totally socially acceptable to sort of lose it around death, I did when I finally got to see her shell. And as I was kissing her lifeless face, stroking her hair full of blood, and sensing that she was really gone, I was granted the true realization of the fact that indeed my father was also dead, despite wishful thinking for 20 years.

My father walked into an ice-cold river on Christmas Eve some 20 years ago. He didn’t know how to swim, and thus his mission was suicide. His body was never recovered, so his death was always a bit unreal. Later, my husband played the same suicidal game. His bones, however, were found five years later in the beautiful and breathtaking landscape of the glacier where the entrance to the center of the Earth is supposed to be, at least according to Jules Verne. Thus, that death was also unreal. Yet in this process, I realized the value of the ritual of death. I realized the importance of tears rolling down into the fabric of death: touching, smelling, feeling, and making new memories beyond death.

My brother and I had to leave Denmark before the remains of my mother would be transformed into ashes. We were told we could have the urn with her ashes sent to us. My mother had a boyfriend; they had managed to stick together, based on resentment, for a long time. Perhaps they loved each other, but they had a strange and destructive way of showing it to each other. The boyfriend didn’t want to have a wake for my mother, nor did he want to take part in her funeral in Iceland. He decided to save some money on the shipment of my mother’s ashes. Instead of sending her remains the way they are usually are sent — via plane in a sturdy, solid box — he sent my mother’s remains the inexpensive way: via regular mail. He placed the box with the urn inside a bigger box, and wrapped some newspapers around it. When the ashes arrived, the contents of the box rattled a bit.

My brother and I had to leave Denmark before the remains of my mother would be transformed into ashes. We were told we could have the urn with her ashes sent to us. My mother had a boyfriend; they had managed to stick together, based on resentment, for a long time. Perhaps they loved each other, but they had a strange and destructive way of showing it to each other. The boyfriend didn’t want to have a wake for my mother, nor did he want to take part in her funeral in Iceland. He decided to save some money on the shipment of my mother’s ashes. Instead of sending her remains the way they are usually are sent — via plane in a sturdy, solid box — he sent my mother’s remains the inexpensive way: via regular mail. He placed the box with the urn inside a bigger box, and wrapped some newspapers around it. When the ashes arrived, the contents of the box rattled a bit.

My mother had specifically asked for her remains to be scattered into the same river that my father had walked into. My brother and I thought that was too depressing. We wanted to have a grave, at last, to visit. Visiting her at our father’s suicide point just didn’t feel right, despite the beautiful landscape. My grandmother wanted to honor my mother’s last wishes, so there was a rift in the family about this. Being a chronic diplomat at times like this, I got a brilliant yet illegal idea: split the ashes. Some could be put in the old graveyard next to her brother and her father, and some could be scattered in the cold river to be united with the spirit of our father. In Iceland, the laws say that ashes must either be scattered in one place or be buried. So after all, it was good that she came in the regular mail — we could do whatever we felt was right.

I had offered to split the ashes between the urn and a container that looked like an old milk carton. I had the box next to my bed; I was imagining how dramatic it would be to perform this task. Finally, one night before the burial ceremony, I took the box to the living room. I opened it slowly and found out that the lid of the urn had opened and the ashes had scattered all over the bigger box. I thought, “What the fuck, shit, damn should I do?” In a panic, I took the box out to the balcony, and then I thought, “She never liked being placed in a box anyway,” and I laughed, hard. This was just too bizarre, like a Charlie Chaplin film. I took the container out and tried to pour the ashes back into it and the urn, but so much of it had spilled out that some of it was on the balcony, some of it was on my hands, and some of it took flight with the sharp wind. At this point I thought, “Why not take this all the way? This is not half as disgusting as I thought it would be. This is like beautiful shells, like beach sand,” and I liked it.

So I got out my ladybug box. I had kept my children’s baby teeth and a lock from each of their first haircut in it. I emptied it out and poured some of the ashes into the belly of the ladybug. I decided to place inside the urn stuff that reminded me of my mother. I knew she would be happy to have certain personal items close to her earthly remains. I placed a little guitar pin, a lighter shaped like a cigarette, and a heart-shaped piece of paper that said “I love you” in her ashes. It felt really good. Then I took some photos of the urn, and thus the photo journey began. Later that night I had to blow my nose, and I realized that I had literally snorted my mother into my nose, because the stuff that came out of my nose was ash. I realized that my mother and I had gone full circle. I used to be in her belly, a part of her, and now she was in my bloodstream, thus a part of me. And this was beautiful and funny at the same time. I was at peace.

Shortly after we scattered her ashes and buried the rest, I was chanting. I had the ladybug on my altar. I suddenly got a very strong sense that my mother wanted me to take the ladybug with me as I went around my daily life. So I did. This photo journey is the making of new memories, the full circle, the forgiving — the alchemist of life changing poison into healing medicine. No one can escape death, yet we, in our modern-day life, have alienated the ritual of death from our daily lives, from our hearts, from our core being. This is my attempt to create a new ritual from an ancient one.

Shortly after we scattered her ashes and buried the rest, I was chanting. I had the ladybug on my altar. I suddenly got a very strong sense that my mother wanted me to take the ladybug with me as I went around my daily life. So I did. This photo journey is the making of new memories, the full circle, the forgiving — the alchemist of life changing poison into healing medicine. No one can escape death, yet we, in our modern-day life, have alienated the ritual of death from our daily lives, from our hearts, from our core being. This is my attempt to create a new ritual from an ancient one.

When I was a kid, my great-grandmother died at my grandfather’s home while performing her daily ritual of foot bathing. My grandparents kept her body in their bedroom for a few days. There she was, so peaceful in her casket, for family and friends to experience the moment of “good-bye,” to create new memories in the peaceful ambience of a private home. This ritual has almost vanished. People now die in old people homes. If you are lucky, you get to see the body during a hurried ceremony, and then it is all over.

The ladybug concept can be used by anyone who needs new memories, who needs to weave life into death, and to change grief into joy.

[Click here to enter the photo essay.]

Related pieces:

SONG—When the violin is silent

POEM—Songbird

Birgitta Jonsdottir

Dear Reader,

In The Fray is a nonprofit staffed by volunteers. If you liked this piece, could you

please donate $10? If you want to help, you can also:

Seeking the zen of the present moment.

Seeking the zen of the present moment.

An attempt at silence.

An attempt at silence.

Like so many true artists, despite all her faults, she was greater than life. During her last years on this planet, she lost the connection with her creative muse. She withdrew further into her disease and self-destructive patterns. She told no one how ill she was as she dealt with lung cancer on her own in another country: no drugs, no operations, no hospitals. She was doing this death battle as was done in the old days: She knew her time on this planet was coming to an end, and she didn’t fight it. She didn’t want to change anything.

Like so many true artists, despite all her faults, she was greater than life. During her last years on this planet, she lost the connection with her creative muse. She withdrew further into her disease and self-destructive patterns. She told no one how ill she was as she dealt with lung cancer on her own in another country: no drugs, no operations, no hospitals. She was doing this death battle as was done in the old days: She knew her time on this planet was coming to an end, and she didn’t fight it. She didn’t want to change anything. My brother and I had to leave Denmark before the remains of my mother would be transformed into ashes. We were told we could have the urn with her ashes sent to us. My mother had a boyfriend; they had managed to stick together, based on resentment, for a long time. Perhaps they loved each other, but they had a strange and destructive way of showing it to each other. The boyfriend didn’t want to have a wake for my mother, nor did he want to take part in her funeral in Iceland. He decided to save some money on the shipment of my mother’s ashes. Instead of sending her remains the way they are usually are sent — via plane in a sturdy, solid box — he sent my mother’s remains the inexpensive way: via regular mail. He placed the box with the urn inside a bigger box, and wrapped some newspapers around it. When the ashes arrived, the contents of the box rattled a bit.

My brother and I had to leave Denmark before the remains of my mother would be transformed into ashes. We were told we could have the urn with her ashes sent to us. My mother had a boyfriend; they had managed to stick together, based on resentment, for a long time. Perhaps they loved each other, but they had a strange and destructive way of showing it to each other. The boyfriend didn’t want to have a wake for my mother, nor did he want to take part in her funeral in Iceland. He decided to save some money on the shipment of my mother’s ashes. Instead of sending her remains the way they are usually are sent — via plane in a sturdy, solid box — he sent my mother’s remains the inexpensive way: via regular mail. He placed the box with the urn inside a bigger box, and wrapped some newspapers around it. When the ashes arrived, the contents of the box rattled a bit. Shortly after we scattered her ashes and buried the rest, I was chanting. I had the ladybug on my altar. I suddenly got a very strong sense that my mother wanted me to take the ladybug with me as I went around my daily life. So I did. This photo journey is the making of new memories, the full circle, the forgiving — the alchemist of life changing poison into healing medicine. No one can escape death, yet we, in our modern-day life, have alienated the ritual of death from our daily lives, from our hearts, from our core being. This is my attempt to create a new ritual from an ancient one.

Shortly after we scattered her ashes and buried the rest, I was chanting. I had the ladybug on my altar. I suddenly got a very strong sense that my mother wanted me to take the ladybug with me as I went around my daily life. So I did. This photo journey is the making of new memories, the full circle, the forgiving — the alchemist of life changing poison into healing medicine. No one can escape death, yet we, in our modern-day life, have alienated the ritual of death from our daily lives, from our hearts, from our core being. This is my attempt to create a new ritual from an ancient one.

Braving the border.

Braving the border.

A tribute to fathers from all walks of life.

A tribute to fathers from all walks of life.

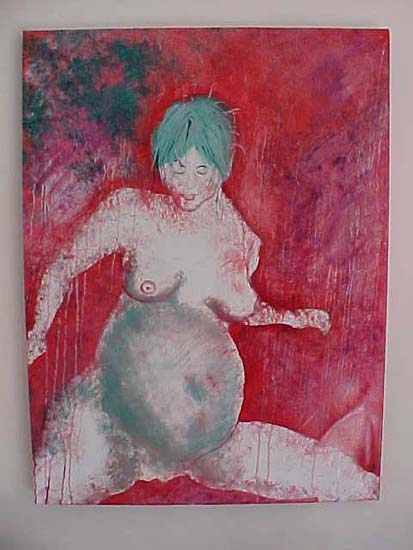

Why eating for two can make a woman think twice about her body image.

Why eating for two can make a woman think twice about her body image.

Images inside abandoned Catskills resorts.

Images inside abandoned Catskills resorts.

Post-war reparations in Guatemala.

Post-war reparations in Guatemala.

Detroit’s transition from past to present.

Detroit’s transition from past to present.